Abstract

Background

The prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae is increasing globally and is a major clinical concern. Between June 2008 and September 2009, 4% of patients in an intensive care unit (ICU) were found to be colonized or infected by strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae multiresistant to ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, and tobramycin; an investigation was initiated and isolates were characterized by molecular typing and resistance patterns.

Methods

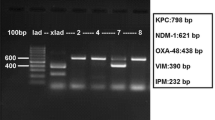

Antibiotic susceptibilities were determined by Vitek2®, Etest®, and agar dilution. Gene encoding beta-lactamases and plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance PMQR determinants (qnr, aac(6′)-Ib) were characterized by PCR, sequencing, and transfer assays. DiversiLab® fingerprints were used to study the relatedness of isolates.

Results

Fourteen isolates co-expressing blaCTX-M15, qnrB1, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr were identified. Genotypic analysis of these isolates identified 12 clonally related strains recovered from 10 patients. The increased prevalence of blaCTX-M15-qnrB1-aac(6′)-Ib-cr-producing K. pneumoniae coincided with the presence in the ICU of a patient originally from Nigeria. This patient was infected by a strain not clonally related to the others but harbouring qnrB1 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes, a finding not hitherto observed in France. We suspected transmission of resistance plasmids followed by rapid dissemination of the multiresistant K. pneumoniae clone by cross-transmission.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of microbiological screening for multidrug-resistant strains in ICUs, particularly among patients from regions in which multidrug-resistant bacteria are known to exist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The increasing prevalence of infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms is a cause for grave concern among healthcare professionals, in particular within intensive care units (ICU). The wide spread of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae is increasing globally and poses a major clinical problem in many countries [1]. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR), especially involving Qnr proteins and the aminoglycoside acetyltransferase variant determinant (AAC(6′)-Ib-cr), has emerged and is now described worldwide [2]. PMQR determinants are generally reported in association with ESBL-producing enterobacteria, in particular the CTX-M type [2, 3]. Herein, we describe the investigation of an outbreak in a French ICU of a strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing QRN-B and CTX-M-15-type enzymes.

Methods

Between June 2008 and September 2009, the incidence of colonization or infection with K. pneumoniae strains multiresistant to ceftazidime (MIC > 4 mg/l), ciprofloxacin (MIC > 1 mg/L), and tobramycin (MIC > 4 mg/l) increased to 4% in the medical ICU of the Clinique Mutualiste, a 195-bed hospital centre equipped with 12 ICU beds (220 patients admitted annually). The medical files and microbiological data of patients colonized or infected with K. pneumoniae were reviewed. PCR amplification of blaCTX-M, aac(6′)-Ib, qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS sequences was performed as described by other authors [2, 4, 5]. All PCR products positive for aac(6′)-Ib were further analyzed by digestion with Bts CI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) to identify aac(6′)-Ib-cr, which lacks the Bts CI restriction site found in the wild-type gene [3]. All other PCR products obtained were sequenced. Transferability of qnr and bla-CTX-M genes was studied by means of a conjugation assay using streptomycin-resistant E. coli J53 as the recipient. After 40 minutes of incubation, mating mixtures were plated onto agar containing streptomycin (100 mg/l) and ceftazidime (1 mg/l). The presence of qnr and bla CTX-M in the transconjugants was confirmed by PCR as described above. Clonal relationships also were investigated using the DiversiLab® fingerprinting system (bioMérieux), a commercially available repetitive-element (rep)-PCR tool successfully used for the typing of ESBL-producing E. coli isolates [6]. This study was conducted only on bacterial samples without changing the medical care of patients. It does not therefore fall within the French law on biomedical research and has not received notice of an ethics committee.

Results and Discussion

The outbreak exhibited two major peaks: one in the summer of 2008 and another in the summer of 2009; no clinical cases were noted before June 2008, between these two periods, or after September 2009 (Figure 1) (Additional file 1: Figure S1). During the 15-month period of the outbreak, 17 patients (aged 37-86 years) exhibited a total of 21 isolates (Figure 2). Following identification of the outbreak, control measures were reinforced. Patients were placed in a specific area of the ward under the supervision of specially assigned staff members in order to reduce the risk of cross-transmission. During the second summer outbreak in 2009, all ICU sinks were screened for the presence of multidrug-resistant bacteria. Three sinks were found to be positive for CAZ-CIP-TM resistant K. pneumoniae: two in patient’s rooms and one in the nurses’ room. Fourteen of the 21 clinical CAZ-CIP-TM-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates were positive for blaCTX-M15,qnrB1, and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes. Of the 14 K. pneumoniae strains harbouring aac(6′)-Ib-cr and qnrB1 genes isolated from 11 patients, 12 displayed the same DiversiLab® pattern (pattern 1, Figure 2), whereas 2 isolates from patient 1 showed a distinct profile (pattern 2, Figure 2). Furthermore, molecular typing confirmed that the three isolates collected from the sinks belonged to the same cluster (pattern 1, Figure 2). The first isolates (patient 1, strains 1.56 and 1.86) of K. pneumoniae harbouring qnrB1 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene were recovered from a patient from Nigeria who was admitted for biliary peritonitis. This patient, infected with a strain of K. pneumoniae expressing a QnrB1 protein, may be considered the index case. We suspected plasmid transfer from a Nigerian K. pneumoniae strain to another K. pneumoniae strain, and conferring high-level resistance to antimicrobial drugs. The arguments in favour of this hypothesis were as follows: (i) no cases of infection by multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae had been reported before admission of the suspected index patient, (ii) QnrB1 had been described previously in Africa but not in France [7–9], (iii) E. coli transconjugants with qnr and bla-CTX-M gene were obtained from this African K. pneumoniae strain, and (iv) the outbreak was terminated after eradication of potential reservoirs in the environment coupled with increased hygiene measures. Klebsiella infections may have spread rapidly as a result of environmental contamination (medical devices, soap, and disinfectants) or cross-transmission via the hands of healthcare workers [10]. In our study, epidemic K. pneumoniae strains were isolated from both patients and sinks (patients’ rooms and the nurses’ room), suggesting that contaminated water points could act as a secondary reservoir with a risk of contamination during handwashing. After reinforcement of hygiene measures, including cleaning of the environment within unit and replacement of the sinks, the outbreak ended. In the ICU, prior to this outbreak, no active surveillance of multiresistant bacteria was performed. However, such surveillance with isolation should form an active component of infection-control bundles to prevent the proliferation of multiresistant bacteria [11].

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report an outbreak in a French ICU of a multiresistant K. pneumoniae strain possibly introduced from Africa. In France, very recent recommendations call for routine screening for multidrug-resistant bacteria in patients admitted to ICUs, particularly those repatriated from abroad (http://www.sf2h.net) (http://hcsp.fr). In practice, rectal swabbing or stool culture must be performed for such patients, with concomitant implementation of additional contact precautions to prevent cross-transmission. The results of our investigation clearly support the value of these new recommendations in preventing the diffusion of multiresistant strains among debilitated patients.

References

Canton R, Gonzalez-Alba JM, Galan JC: CTX-M enzymes: origin and diffusion. Front Microbiol 2012, 3: 110.

Cattoir V, Poirel L, Rotimi V, Soussy CJ, Nordmann P: Multiplex PCR for detection of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance qnr genes in ESBL-producing enterobacterial isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 60: 394–397. 10.1093/jac/dkm204

Kim HB, Park CH, Kim CJ, Kim EC, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC: Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants over a 9-year period. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009, 53: 639–645. 10.1128/AAC.01051-08

Pitout JD, Hamilton N, Church DL, Nordmann P, Poirel L: Development and clinical validation of a molecular diagnostic assay to detect CTX-M-type beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007, 13: 291–297. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01645.x

Peirano G, Pitout JD: Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M beta-lactamases: the worldwide emergence of clone ST131 O25:H4. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010, 35: 316–321. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.003

Pitout JD, Campbell L, Church DL, Wang PW, Guttman DS, Gregson DB: Using a commercial DiversiLab semi-automated repetitive sequence-based PCR typing technique for identification of Escherichia coli clone ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Clin Microbiol 2009, 47: 1212–1215. 10.1128/JCM.02265-08

Soge OO, Adeniyi BA, Robert MC: New antibiotic resistance genes associated with CTX-M plasmids from uropathogenic Nigerian Klebsiella pneumoniae . J Antimicrob Chemother 2006, 58: 1048–1053. 10.1093/jac/dkl370

Dahmen S, Poirel L, Mansour W, Bouallègue O, Nordmann P: Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants in Enterobacteriaceae from Tunisia. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010, 16: 1019–1023.

Karah N, Poirel L, Bengtsson S, Sundqvist M, Kahlmeter G, Nordmann P, Sundsfjord A, Samuelsen O: Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnr and aac(6′)-Ib-cr in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. from Norway and Sweden. Diag Microbiol Infect Dis 2010, 66: 425–431. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.12.004

Berthelot P, Grattard F, Patural H, Ros A, Jelassi-Saoudin H, Pozzetto B, Teyssier G, Lucht F: Nosocomial colonization of premature babies with Klebsiella oxytoca : probable role of enteral feeding procedure in transmission and control of the outbreak with the use of gloves. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2001, 22: 148–151. 10.1086/501881

Cohen J: Confronting the threat of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in critically ill patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013, 68: 490–491. 10.1093/jac/dks460

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. P. Nordmann and Dr. L. Poirel for their gift of isolates of E. coli Lo positive for qnrA1, of K. pneumoniae B15 positive for qnrB1, of E. cloacae 287 positive for qnrS1, of E. coli DIT positive for aac(6′)-Ib-cr, and of E. coli BicA positive for qepA.

The authors are indebted to the following contributors at the Clinique Mutualiste: Monique Brun, infection control nurse, and Dr. Pascal Pain, head of the infection control committee.

This research has received funding support (No. 0808070) from the University Hospital of Saint Etienne.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The authors carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Filippa, N., Carricajo, A., Grattard, F. et al. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying qnrB1 and bla CTX-M15 in a French intensive care unit. Ann. Intensive Care 3, 18 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-3-18

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-3-18