Abstract

Background

Limited studies are available on prevalence and severity of vitamin D deficiency in a critically ill population. To the best of our knowledge, this the first study of its kind in an Indian intensive care set-up.

Methods

One hundred fifty-eight critically ill patients were prospectively enrolled for over 2 years. Demographic profile and clinical characteristics were noted. Blood sample for serum 25 (OH) D was collected on admission (4 ml). Serum 25 (OH) D was measured using radioimmunoassay kit. Vitamin D deficiency was labelled as insufficient (31–60 nmol/l), deficient (15–30 nmol/l) and undetectable (<15 nmol/l). Statistical tests used were t test, chi-square test and binary logistic regression.

Results

Vitamin D deficiency (<60 nmol/l) was present in 127 patients (80.4%). Twenty-six patients had (20.47%) undetectable vitamin D levels. The mean vitamin D level was higher amongst survivors (43.17 + 39.22) than in non-survivors (39.72 + 29.31). Vitamin D was not significantly associated with mortality in univariate analysis. Multiple logistic regression showed admission APACHE II (p = 0.008), lactate (p = 0.013) and pre-ICU hospital stay (p = 0.041) as independent predictors of mortality in critically ill patients (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in critically ill patients. A causal association between vitamin D deficiency and mortality was not found in our study. Larger studies are needed to understand the relationship between vitamin D deficiency and ICU outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The pandemic of vitamin D deficiency even in effluent societies has pointed out the growing distance of human race from nature. Recent research has generated interest in pleiotropic actions of vitamin D all over the world.

Vitamin D receptors are found in nearly all types of immune cells [1]. Its action on innate immunity is stimulatory, while its action on adaptive immunity is mainly considered to be modulatory [2]. Various clinical studies and trials have shown correlation between vitamin D and systemic infections. Its deficiency has been associated with acute respiratory tract infections [3, 4], cardiovascular diseases and other chronic illnesses [5]. Scientists are now exploring its possible association with acute life-threatening illnesses. A large US-based study reviewing national database of hospital discharge from 1979 to 2003 showed seasonal variation in incidence of sepsis and severe sepsis paralleling the seasonal fluctuation in 25(OH) D levels [6, 7]. A recently published study showed that vitamin D deficiency prior to hospital admission predisposes for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients [8]. We conducted this study to analyse the prevalence and severity of vitamin D deficiency in a critically ill Indian population as there is paucity in Indian literature.

Methods

It is a prospective single-centre study conducted in the department of critical care medicine of a tertiary care public referral hospital. The intensive care unit (ICU) admits both medical and surgical cases. Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical committee of Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences before conducting the study. Informed consent was taken from next of kin of all enrolled patients. This study was conducted between May 2010 and May 2012.

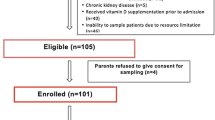

All consecutive critically ill patients requiring ICU admission were screened for enrolment for the study. Exclusion criteria included age less than 18 years, pregnancy, patients on corticosteroid therapy, patients with history of malabsorption syndrome, patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), patients on drugs interfering with vitamin D metabolism and patients already on vitamin D supplementation. A total of 158 patients (out of 480 admissions) met the inclusion criteria, and data was analysed for them.

Blood samples for laboratory measurements of serum 25 (OH) D were collected on patients' admission (4 ml), which were then immediately transferred to the endocrinology laboratory. Serum 25 (OH) D was measured using a radioimmunoassay kit technique using the 12 well gamma Counter machine (STRATEC, Birkenfeld, Germany). Till the samples were not processed, they were stored at −20°C temperature after separating the serum. Vitamin D deficiency was defined as values less than 60 nmol/l. Severity of vitamin D deficiency was labelled as insufficient if the level was between 31 and 60 nmol/l, deficient if the level was between 15 and 30 nmol/l and undetectable if the level was less than 15 nmol/l. The demographic profile (age/sex, co-morbidities), admission diagnosis, clinical characteristics and biochemical parameters of each patient were noted at the time of enrolment in the study. Severity of critical illness was assessed by admission acute physiological and chronic health evaluation (APACHE II) score and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score. Levels and severity of vitamin D deficiency were compared between survivors and non-survivors and correlated with the outcome. Vitamin D was also compared to other predictors of outcome like APACHE II, SOFA and total days of mechanical ventilation. Laboratory and clinical management was done as per the treating team.

Statistical analysis

Data was analysed using SPSS 16.0, and results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. Sample size was decided based on significance level (alpha) = 0.05. Student's t test was used between survivors and non-survivors. Non-parametric test like chi-square test was used for comparison between two groups for ranked observation. Actual p values were reported, and a p value <0.05 was taken as significant. Multivariate analysis by binary logistic regression was used. All the study variables were considered, and the best model with five variables which gave 90.5% overall correct classification was used.

Results and discussion

Results

Of the 158 patients enrolled in the study, there were 97 male patients (61.39%) and 61 female patients (38.60%). Their mean age, SOFA score, APACHE II score, Vitamin D levels, average length of stay and average days of mechanical ventilation are mentioned in Table 1.

Survivors and non-survivors were compared for demographic characteristics like age, severity of illness (SOFA and APACHE II) and admission laboratory parameters which included procalcitonin (PCT), serum albumin, arterial lactate, serum creatinine and levels of vitamin D (Table 2). Admission SOFA, APACHE II score, lactates, days of mechanical ventilation and days of pre-ICU stay were significantly higher in non-survivors on univariate analysis. There was no statistically significant difference in vitamin D levels amongst the two groups (p = 0.53).

Vitamin D deficiency (<60 nmol/l) was present in 127 patients (80.4%). Fifty-three patients (41.73%) were in the insufficient group, 48 patients (37.79%) were in the deficient group and 26(20.47%) patients had undetectable vitamin D levels.

Factors found to be significantly associated with mortality in univariate analysis (SOFA score, APACHE II score, lactate, pre-ICU stay and days of mechanical ventilation) were subjected to binary logistic regression. APACHE II score, lactate and pre-ICU stay were found to be independently associated with mortality (Table 3).

Discussion

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in the general population all over the world. Prevalence of levels <50 nmol/l is reported between 36% and 57% in the USA and even higher (between 28% and 100%) in European studies depending upon the group of population tested and cut-off levels used for normal range [9]. Even Indian literature suggests vitamin D deficiency between 50% and 90% in the general population [10, 11].

Cut-off value of normal range of vitamin D remains a debatable topic, and whether levels considered normal for general population can be applied to critically ill patients remains unclear [12, 13]. In our study, we have used 60 nmol/l as the cut-off value based on the study published by Lee et al. in 2009 [14]. However, in a recent meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies, Zitterman and colleagues reported 75–87.5 nmol/l as the optimal concentration in the general population and even showed a non-linear decrease in mortality as circulating 25 (OH) D level increases [15].

Vitamin D deficiency and its relation with increased mortality in the general population are well established. Almost all chronic illnesses associated with ageing are adversely affected by vitamin D deficiency [16, 17]. A meta-analysis published in 2007 showed that ordinary dose vitamin D supplementation is associated with reduction in total mortality in the general population [18]. Melamed and colleagues reported that vitamin D <17.5 ng/l is independently associated with mortality in the general population [19]. Review of literature and clinical studies on end-stage renal disease patients have shown that vitamin D supplementation is associated with decreased mortality [20]. A recently published meta-analysis of 10 studies with a cohort of 6,853 patients concluded that higher vitamin D levels correlates with improved survival in CKD patients [21].

Vitamin D deficiency in critical illnesses can be multifactorial and can influence the sepsis cascade through several mechanisms. These mechanisms may include immune modulation, suppression of exaggerated inflammatory response, enhanced phagocytosis, chemotaxis, increased production of antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin, and calcium and glucose homeostasis [22, 23].

Deficiency of vitamin D in a critically ill population has also been studied, though to a lesser extent. Its association with mortality in this population subgroup remains unclear. Studies have shown a vitamin D deficiency of more than 90% in a critically ill population [24, 25]. Lee et al. reported undetectable levels in 17.5% of patients admitted to the ICU [14]. Data regarding vitamin D deficiency in the critically ill population in the Indian scenario is lacking. In our study, we found that 80.4% of patients were deficient (level <60 nmol/l) in vitamin D levels on admission to the intensive care unit, with 20.48% having undetectable levels (level <15 nmol/l). However, we could not find a causal relationship between vitamin D deficiency and mortality.

Cecchi et al. conducted a single-centre study on 170 patients, out of which 92 were severe sepsis/septic shock patients and 72 were trauma patients [26]. Vitamin D levels were significantly lower in the septic group but did not prove to be a mortality predictor on multivariate analysis. In contrast, a few studies have shown a significant association between vitamin D levels and mortality in critically ill patients [27, 28]. Mathews et al. studied the effect of vitamin D deficiency in 258 surgical ICU patients and reported an inverse relation between vitamin D deficiency and length of ICU stay, cost of therapy and mortality [29]. Braun et al. studied pre-admission 25(OH) D levels drawn 7 to 365 days prior to ICU admission in a large cohort of 2,399 patients [30]. They reported vitamin D as a strong predictor of ICU mortality. It is postulated that acute fluid shifts seen in severe sepsis and septic shock can influence the assessment of correct vitamin D levels [31]. Venkatesh et al. pointed out the wide fluctuation in vitamin D level occurring in critically ill patients for hours [32]. This could be one of the causes of different findings in various studies.

Larger studies are needed to understand the role of vitamin D level in critical illness, to define supplementation strategy, in monitoring frequency and in effect of replacement on outcome. Moreover, redesigning of ICU set-ups in such a way that all patients get adequate sunlight might be a topic of debate in modern medicine.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that this study shows high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in critical care settings even in tropical countries like India. We also found that APACHE II, lactate and pre-ICU hospital stay are independent predictors of mortality in critically ill patients. We could not find a causal association between vitamin D deficiency and mortality.

References

Aranow C: Vitamin D and the immune system. J Investig Med. 2011, 59 (6): 881-886.

Kempker JA, Han JE, Tangpricha V, Ziegler TR, Martin GS: Vitamin D and sepsis: an emerging relationship. Dermatoendocrinol. 2012, 4 (2): 101-108. 10.4161/derm.19859.

Ginde AA, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA: Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and upper respiratory tract infection in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2009, 169: 384-390. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.560.

Sabetta JR, DePetrillo P, Cipriani RJ, Smardin J, Burns LA, Landry ML: Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and the incidence of acute viral respiratory tract infections in healthy adults. PLoS One. 2010, 5: e11088-10.1371/journal.pone.0011088.

Anagnostis P, Athyros VG, Adamidou F, Florentin M, Karagiannis A: Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: a novel agent for reducing cardiovascular risk?. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2010, 8 (5): 720-730. 10.2174/157016110792006978.

Danai PA, Sinha S, Moss M, Haber MJ, Martin GS: Seasonal variation in the epidemiology of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007, 35: 410-415. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253405.17038.43.

Maxwell JD: Seasonal variation in vitamin D. Proc Nutr Soc. 1994, 53: 533-543. 10.1079/PNS19940063.

Braun AB, Litonjua AA, Moromizato T, Gibbons FK, Giovannucci E, Christopher KB: Association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and acute kidney injury in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2012, 40 (12): 1-7.

Holick MF: High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006, 81 (3): 353-373. 10.4065/81.3.353.

Goswami R, Mishra SK, Kochupillai N: Prevalence & potential significance of vitamin D deficiency in Asian Indians. Indian J Med Res. 2008, 127 (3): 229-238.

Harinarayan CV, Joshi SR: Vitamin D status in India—its implications and remedial measures. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009, 57: 40-48.

Lee P: How deficient are vitamin D deficient critically ill patients?. Crit Care. 2011, 15: 154-10.1186/cc10126.

Lee P: Vitamin D metabolism and deficiency in critical illness. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 25 (5): 769-781. 10.1016/j.beem.2011.03.001.

Lee P, Eisman JA, Center JR: Vitamin D deficiency in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360: 1912-1914. 10.1056/NEJMc0809996.

Zittermann A, Iodice S, Pilz S, Grant BW, Bagnardi V, Gandini S: Vitamin D deficiency and mortality risk in the general population: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95: 91-100. 10.3945/ajcn.111.014779.

Raiten DJ, Picciano MF: Vitamin D and health in the 21st century: bone and beyond. Executive summary. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 80: 1673S-1677S.

Holick MF: Vitamin D: importance in the prevention of cancers, type 1 diabetes, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 79: 362-371.

Autier P, Gandini S: Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167 (16): 1730-1737. 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730.

Melamed M, Michos E, Post W, Astor B: 25-Hydroxyl vitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168 (15): 1629-1637. 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1629.

Teng M, Wolf M, Ofsthun MN, Lazarus JM, Hernán MA, Camargo CA, Thadhani R: Activated injectable vitamin D and hemodialysis survival: a historical cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005, 16 (4): 1115-1125. 10.1681/ASN.2004070573.

Pilz S, Iodice S, Zittermann A, Grant WB, Gandini S: Vitamin D status and mortality risk in CKD: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011, 58 (3): 374-382.

Lee P, Nair P, Eisman JA, Center JR: Vitamin D deficiency in the intensive care unit: an invisible accomplice to morbidity and mortality?. Intensive Care Med. 2009, 35 (12): 2028-2032. 10.1007/s00134-009-1642-x.

Hewison M: Vitamin D and the immune system: new perspectives on an old theme. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2010, 39: 365-379. 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.02.010.

Lucidarme O, Messai E, Mazzoni T, Arcade M, du Cheyron D: Incidence and risk factors of vitamin D deficiency in critically ill patients: results from a prospective observational study. J Intensive Care Med. 2010, 36 (9): 1609-1611. 10.1007/s00134-010-1875-8.

Flynn L, Zimmerman LH, McNorton K, Dolman M, Tyburski J, Baylor A, Wilson R, Dolman H: Effects of vitamin D deficiency in critically ill surgical patients. Am J Surg. 2012, 203 (3): 379-382. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.09.012.

Cecchi A, Bonizzoli M, Douar S, Mangini M, Paladini S, Gazzini B, Degl’Innocenti S, Linden M, Zagli G, Peris A: Vitamin D deficiency in septic patients at ICU admission is not a mortality predictor. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011, 77 (12): 1184-1189.

Braun AB, Gibbons FK, Litonjua AA, Giovannucci E, Christopher KB: Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D at critical care initiation is associated with increased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2012, 40: 63-72. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822d74f3.

Arnson Y, Gringauz I, Itzhaky D, Amital H: Vitamin D deficiency is associated with poor outcomes and increased mortality in severely ill patients. Q J Med. 2012, 105: 633-639. 10.1093/qjmed/hcs014.

Matthews LR, Ahmed Y, Wilson KL, Griggs DD, Danner OK: Worsening severity of vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased length of stay, surgical intensive care unit cost, and mortality rate in surgical intensive care unit patients. Am J Surg. 2012, 204 (1): 37-43. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.07.021.

Braun A, Chang D, Mahadevappa K, Gibbons FK, Liu Y, Giovannucci E, Christopher KB: Association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and mortality in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2011, 39: 671-677. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206ccdf.

Krishnan A, Ochola J, Mundy J, Jones M, Kruger P, Duncan E, Venkatesh B: Acute fluid shifts influence the assessment of serum vitamin D status in critically ill patient. Crit Care. 2010, 14 (6): R216-10.1186/cc9341.

Venkatesh B, Davidson B, Robinson K, Pascoe R, Appleton C, Jones M: Do random estimations of vitamin D3 and parathyroid hormone reflect the 24-h profile in the critically ill?. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38: 177-179. 10.1007/s00134-011-2415-x. Suggests that 25(OH)D levels fluctuate widely during critical illness

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to DR SK Mandal for his guidance and valuable inputs in our research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

This is a statement confirming that all authors have read and accept the “Terms and Conditions for Anaesthesia and Intensive Care submissions” as outlined in the online submission process. AA principal investigator, writing of paper and review of literature. AA sample collection and writing of the paper. SY sample processing and reviewing of literature. AKB reviewing of literature. MG manuscript preparation. MMG manuscript preparation. BP final editing. RKS final editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Azim, A., Ahmed, A., Yadav, S. et al. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in critically ill patients and its influence on outcome: experience from a tertiary care centre in North India (an observational study). j intensive care 1, 14 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-0492-1-14

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-0492-1-14