Abstract

Background

Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) is the most common primary malignant tumor of the central nervous system. Standard of care includes maximal resection followed by chemoradiotherapy. Tumors need adequate perfusion and neovascularization to maintain oxygenation and for removal of wastes. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a well characterized pro-angiogenic factor. We hypothesized that the increases in urinary VEGF levels would occur early in the course of tumor recurrence or progression. We examine the feasibility of collecting and analyzing urinary VEGF levels in a prospective, multi-institutional trial (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group, RTOG, 0611) as well as the role of VEGF as a marker of tumor recurrence.

Method

We evaluated VEGF levels in urine specimens collected post-operatively, at the conclusion of radiation therapy (RT) and one month following RT. Urinary VEGF levels were correlated with tumor progression at one year. VEGF levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay in urine specimens and normalized to urinary creatinine levels. Sample size was determined based on a 50% 1-year recurrence rate. With a sensitivity and specificity of 80%, the expected 95% confidence interval was (0.69, 0.91) with 100 patients. A failure was defined as documented disease progression, recurrence or death before one year.

Results

202 patients were enrolled between February-2006 and October-2007. Four patients were ineligible as they did not receive RT. Of the remaining 198 patients, 128 had all three samples collected. In this group, 35 patients (27.3%) did not progress, 89 (69.5%) had progression and 4 (3.1%) died without evidence of progression. Median VEGF levels at baseline were 52.9 pg/mg Cr (range 0.2- 15,034.4); on the last day of RT, 56.6 (range 0–2,377.1); and at one month follow-up, 70.0 (range 0.1-1813.2). In patients without progression at 1-year, both baseline VEGF level and end of RT VEGF level were lower than those of patients who progressed: 40.3 (range 0.2-350.8) vs. 59.7 (range 1.3-15,034.4) and 41.8 (range 0–356.8) vs. 69.7 (range 0–2,377.1), respectively. This did not reach statistical significance. Comparison of the change in VEGF levels between the end of RT and one month following RT, demonstrated no significant difference in the proportions of progressors or non-progressors at 1-year for either the VEGF increased or VEGF decreased groups.

Conclusion

Urine can be collected and analyzed in a prospective, multi-institutional trial. In this study of patients with GBM a change in urinary VEGF levels between the last day of RT and the one month following RT did not predict for tumor progression by one year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) is the most frequent primary malignant brain tumor in adults [1, 2]. Its treatment generally includes maximally safe surgical resection followed by adjuvant radiation therapy and temozolomide chemotherapy [3]. Despite advances in understanding the biology behind GBM [1, 4, 5] and some improvement in outcome with the addition of temozolomide chemotherapy, its prognosis remains grim with a median overall survival (OS) of 15 months [6].

Personalized therapy based on tumor biology in individual patients to improve treatment outcome has identified several potential biomarkers [5, 7, 8], including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [9]. Increased VEGF activity has been associated with early recurrence in patients with cancer including GBM [10–12]. VEGF can be measured in biofluids such as urine, serum or plasma [13–15]. The measurement of VEGF in urine is an attractive option as urine collections are noninvasive, there are minimal preparation costs and urinary proteins are stable during long term storage [16, 17]. In addition, the measurement of VEGF in serum or plasma can be problematic as VEGF can be released by platelets in the process of phlebotomy in the case of serum [15] and sequestration of VEGF within platelets may make accurate VEGF measurement difficult in the case of plasma [13, 14]. VEGF as a urinary biomarker has previously been shown to be a predictive marker for progression free survival (PFS) in cancer patients after the completion of radiotherapy (RT) [10]. Its potential importance to the treatment of GBM is based on its role in pro-angiogenesis.

VEGF is responsible for increased vascularity and vascular permeability in tumors as well as migration and proliferation of endothelial cells [18, 19]. VEGF mRNA has been identified in pseudopalisading cells around necrotic zones in GBM and its expression correlates with grade in diffuse astrocytomas [20]. We hypothesized that increased urinary VEGF levels would predict for recurrence or progression in patients with GBM patients. The purpose of this study was to examine the feasibility of collecting and analyzing urine in a prospective, multi-institutional trial and the potential utility of urinary VEGF as a predictive biomarker for progression. In order to explore the dynamic nature of this potential relationship, VEGF was measured in the urine of GBM patients prior to radiation therapy, at completion and at 1 month follow-up.

Materials and methods

Specimen and data collection

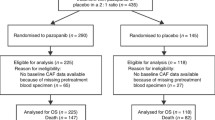

Under institutional review board approval, following informed consult, voided urine samples were collected from 202 subjects with a diagnosis of primary GBM between February 2006 and October 2007 on RTOG study 0611. This study was approved by the National Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board. A patient was considered eligible if he/she was enrolled on an RTOG GBM study (RTOG 0513 or RTOG 0525). RTOG 0525 is a two arm study in which patients were randomized to receive either standard adjuvant temozolomide therapy or dose dense adjuvant temozolomide [21]. RTOG 0513 is a phase I/II trial in which patients received Motexafin Gadolinium in one of 3 dose levels in phase I, followed by the Motexafin Gadolinium maximum tolerated dose in phase II in conjunction with standard treatment [22]. Among 202 enrolled, 4 patients were subsequently considered ineligible as they did not receive radiation therapy. Of these 198 patients, adequate specimen for analysis at all three time points was available for 128 patients. The urine collection protocol and the need for adequate specimens and analysis have been previously described [16, 17]. A minimum of 5 cc of urine was collected from each patient at baseline, at the completion of radiation therapy, and at the 1 month follow-up evaluation.

Specimen processing and analysis

Urine samples were sent by overnight courier covered with dry ice to a central laboratory for processing and storage. They were measured using a commercial ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay) system for VEGF (R&D systems) as per previously published material [16, 17]. Urine creatinine levels were measured using the Bayer DCA 2000 following standard protocol [16, 17].

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated to determine estimates of sensitivity and specificity for 1 year recurrence. A 50% 1 year recurrence rate was calculated based on prognostic class average of the RTOG Recursive Partitioning Analysis of Gliomas (RPA) [23, 24]. With a sensitivity and specificity of 80% for progression, the expected 95% confidence interval was (0.82, 0.98) based on 100 patients. We calculated that 200 patients were required to ensure that at least 100 patients would have usable specimens based on a previous 50% rate of unusable specimens.

The distribution of VEGF was described with mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum, Q1 (first quartile) and Q3 (third quartile). For the purposes of calculating PFS a patient was considered to have failed treatment if there was documented disease before 1 year or if the patient died without disease before 1 year. Chi-square tests were used to test the distribution difference of pretreatment characteristics of this study and RTOG 0525 patients that were not used in this study, and failure status at 1 year by the change in VEGF from the end of radiation therapy to 1 month post radiation therapy. A Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was used to determine the best cut off range for predicting recurrence at 1 year. Logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between patient characteristics and recurrence at 1 year. All testing was done at the overall significance level of 0.05. Statistical Analysis System (SAS, Cary, NC) was used to perform these analyses.

Results

Of 202 enrolled patients the demographic, clinical and pathologic characteristics of the patient population were compared to a control set of patients enrolled in RTOG 0525 that were not enrolled in the current study (Table 1). Compared to this reference, the patients analyzed in the current study differ significantly in the extent of surgical resection and neurologic functional status [23]. Patients on the current study were more likely to have had gross total resection (p = 0.01, χ2) and better neurological function (p = 0.02, χ2) compared to the RTOG 0525 reference population. The most prevalent RPA class in our cohort was class IV (57.8%). Fifty-three percent of patients were unmethylated at the O6-methylaguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter and 25% were methylated.

At 1 year, 35 (27.3%) patients had not progressed, 89 (69.5%) had progressed, and 4 (3.1%) died without progression. For the entire group of 128 patients, at baseline the median VEGF level was 52.9 pg/mgCr (range 0.2-15,034.4); on the last day of RT 56.6 pg/mgCr (range 0 – 2,377.1); and at 1 month following RT 70.0 pg/mgCr (range 0.1-1,813.2). In patients who had not progressed at 1 year, both their baseline VEGF levels of 40.3 pg/mgCr (range 0.2-350.8) as well as their end of RT VEGF levels of 41.8 pg/mgCr (range 0–356.8) were lower than the levels in patients who had progressed at one year, 59.7 pg/mgCr (range 1.3-15,034.4) and 69.7 pg/mgCr (range 0–2,377.1), respectively. However, the differences among these groups did not reach statistical significance.

The normalized VEGF change from the end of RT to the 1 month post-RT measurement was compared between patients who progressed by 1-year vs. those that did not progress (Table 2). Chi-square test revealed no significantly higher rate of failure in patients with elevated VEGF at 1 month radiation therapy (p = 0.21). On univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis no significant correlations were identified for any of the variables examined (randomization arm on RTOG 0525, methylation status, RPA class, baseline normalized VEGF, and VEGF change from end of radiation therapy to 1 month follow-up) (Table 3). The area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) is 0.5401, suggesting that VEGF is not a useful biomarker to predict recurrence at 1 year (Figure 1).

Discussion

VEGF has emerged as a significant drug target due to its importance as a pro-angiogenic cytokine in gliomas [4]. VEGF signaling is thought to occur in response to hypoxia and results in the formation of vessels whether de novo or from preexisting vasculature [25]. Its role may be especially important in gliomas as they exhibit aberrant vessels, hypoxia and endothelial proliferation. Increasing VEGF activity correlates with an increase in vascular proliferation and increasing tumor grade in gliomas [26]. A number of drugs aimed at neutralizing VEGF receptors are currently being investigated [9], most notably bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds and neutralizes VEGF. Bevacizumab has been approved for use in non-small cell lung cancer, metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and based on the BRAIN [27] and the NCI 06-C-0064E studies [28] it has also been approved for use in patients with recurrent GBM. The two GBM trials showed a reduction in steroid use, temporary improvement in neurological function and, in the BRAIN study, a PFS of 9.2 months. In the newly diagnosed GBM setting, a phase II trial [29] has shown a PFS benefit with no OS benefit when Avastin is used in conjunction with RT and temozolomide, although subset analysis showed that RPA class IV/V may have an OS benefit as well. The addition of Avastin to the standard regimen of radiation and temozolomide is currently being investigated in large randomized phase III trials (RTOG 0825, BO21990).

Previously, Chan et al. [10] showed that urinary VEGF levels at the end of radiotherapy compared to the level at least 1 month post treatment to be predictive of 1 year PFS in a variety of tumor types, including GBM. Thus, the present study focused on VEGF as a potential biomarker for tumor recurrence in patients with GBM receiving chemoradiation. Our results show that the patient population in the current study is largely representative of the RTOG0525 population, suggesting applicability to GBM patients in general. However, we measured no significant difference with respect to changes in VEGF in the patients who failed treatment and those who did not. Furthermore, no significant correlation was found on univariate/multivariate analysis for either baseline VEGF or the change in VEGF level. However only 25% of patients were found to have methylated MGMT in the current study as compared to historical rates on the order of 45% [5] to 50% [30–32]. As methylated MGMT has been shown to be both prognostic and predictive for an improved outcome in GBM [33–36], this may affect the survival outcome as patients may be more likely to fail treatment. Recent analysis of the RTOG0525 results does not suggest that this is the case as their outcomes are comparable to published literature [31]. Randomization to either arm was not statistically different suggesting that standard chemotherapy vs. dose dense chemotherapy is likely not a confounding factor with respect to urinary VEGF (Table 1).

Limitations of the study include the small number of patients (128) for whom adequate samples were available as well as potentially the timing of VEGF measurement and the lack of long term follow-up of urinary VEGF levels. Although previous data [10] showed a correlation between urinary VEGF levels and PFS in a population of cancer patients, there is the possibility that the correlation with respect to GBM may exist but is simply not being detected in the current study as result of the timing of VEGF measurement. VEGF secretion in quantities large enough to be predictive for recurrence may not occur until a significant burden of disease is present, which is less likely at the end of treatment or even at the 1 month follow-up point. The possibility remains that VEGF levels could in fact be predictive at a later date that is still before a definitive radiographic diagnosis could be made. In such a scenario, they could potentially help distinguish progression from pseudoprogression.

Despite this lack of statistical significance, baseline values for VEGF were higher for patients who progressed by 1 year. This was the case both at baseline as well as at the end of radiotherapy. This may support the idea that at the very least urinary VEGF may have value as a prognostic if not necessarily as a predictive biomarker in GBM.

Recent studies have revealed significant heterogeneity within gliomas and even within the narrowly defined GBM histology [1, 37, 38]. Based on the GBM subtypes identified in Verhaak et al., it is possible that VEGF levels may be predictive in some GBM subtypes specifically the mesenchymal or classical. EGFR activation (classical subtype) and PTEN mutation (mesenchymal subtype) have both been associated with increased VEGF expression [4]. Further studies could examine a possible correlation between VEGF levels and molecular GBM subtypes and possibly include VEGF level within the risk classification itself. A possible correlation between GBM subtypes and VEGF was not addressed in the current study. RTOG 0825, one of the two ongoing phase III trials involving bevacizumab, includes patient stratification by mesenchymal/angiogenic gene expression and may indirectly explore this potential relationship.

Conclusion

Urinary VEGF was not identified as a predictive factor for tumor recurrence in GBM patients receiving radiation therapy. There is a suggestion that baseline and post treatment VEGF levels may be higher in patients who ultimately fail treatment although this was not statistically significant. This study confirmed that urine can be collected and analyzed in a prospective, multi-institutional trial.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this report.

References

Ohgaki H, Kleihues P: Genetic alterations and signaling pathways in the evolution of gliomas. Cancer Sci 2009, 100: 2235–2241. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01308.x

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavanee WK: WHO classification of tumors of the CNS. 4th edition. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2007.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Anaplastic gliomas/Glioblastoma. Accessed 10/1/2013. [http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cns.pdf]

Fischer I, Gagner JP, Law M, Newcomb EW, Zagzag D: Angiogenesis in glioma: biology and molecular pathophysiology. Brain Pathol 2005, 15: 297–310.

Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al.: MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005, 352: 997–1003. 10.1056/NEJMoa043331

Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al.: Effect of radiotherapy with concomittant and adjuvant Temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in randomized phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC Trial. Lancet Oncol 2009, 10: 459–466. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7

Vihinen P, Kähäri VM: Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer: Prognostic markers and therapeutic agents. Int J Cancer 2002, 99: 157–166. 10.1002/ijc.10329

Burke PA, DeNardo SJ: Antiangiogenic agents and their promising potential in combined therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2001, 39: 155–171. 10.1016/S1040-8428(01)00115-9

Robles Irizarry L, Hambardzumyan D, Nakano I, Gladson CL, Ahluwalia MS: Therapeutic targeting of VEGF in the treatment of glioblastoma. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2012,16(10):973–984. 10.1517/14728222.2012.711817

Chan LW, Moses MA, Goley E, Sproull M, Muanza T, Coleman CN, et al.: Urinary VEGF and MMP levels as predictive markers of 1-year progression-free survival in cancer patients treated with radiation therapy: a longitudinal study of protein kinetics throughout tumor progression and therapy. JCO 2004,3(22):499–506.

Zhou ZH, Cui XN, Xing HG, Yan RH, Yao DK, Wang LX: Changes and prognostic value of serum vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Med Princ Pract 2012. Epub ahead of print

Riihijärvi S, Nurmi H, Holte H, Björkholm M, Fluge O, Pedersen LM, et al.: High serum vascular endothelial growth factor level is an adverse prognostic factor for high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with dose-dense chemoimmunotherapya. Eur J Haematol 2012. Epub ahead of print

Hormbrey E, Gillespie P, Turner K, Han C, Roberts A, McGrouther D, et al.: A critical review of vascular endothelial growth factor analysis in peripheral blood: is the current literature meaningful? Clin Exp Metastasis 2002, 19: 651–663. 10.1023/A:1021379811308

Jelkmann W: Pitfalls in the measurement of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor. Clin Chem 2001,47(4):617–623.

Webb NJ, Bottomley MJ, Watson CJ, Brenchley PE: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is released from platelets during blood clotting: implications for measurement of circulating VEGF levels in clinical disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 1998,94(4):395–404.

Kirk MJ, Hayward RM, Sproull M, Scott T, Smith S, Cooley-Zgela T, et al.: Non-patient related variables affecting levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in urine biospecimens. J Cell Mol Med 2008,12(4):1250–1255. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00182.x

Hayward RM, Kirk MJ, Sproull M, Scott T, Smith S, Cooley-Zgela T, et al.: Post-collection, pre-measurement variables affecting VEGF levels in urine biospecimens. J Cell Mol Med 2008,12(1):343–350.

Dvorak HF: Angiogenesis: update 2005. J Thromb Haemost 2005, 3: 1835–1842. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01361.x

Zhang X, Groopman JE, Wang JF: Extracellular matrix regulates endothelial functions through interaction of VEGFR-3 and integrin alpha5beta1. J Cell Physiol 2005, 202: 205–214. 10.1002/jcp.20106

Berkman RA, Merrill MJ, Reinhold WC, Monacci WT, Saxena A, Clark WC, et al.: Expression of the vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factorgene in central nervous system neoplasms. J Clin Invest 1993, 91: 153–159. 10.1172/JCI116165

Gilbert MR, Wang KD, Aldape R, Stupp R, Hegi ME, Jaeckle KA, Armstrong TS, Wefel JS, Won M, Blumenthal A, Mahajan A, Schultz CJ, Erridge SC, Brown PD, Chakravarti A, Curran WJ, Mehta M: RTOG 0525: a randomized phase III trial comparing standard adjuvant temozolomide(TMZ) with a dose-dense (dd) schedule in newly diagnosed glioblastoma [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2011,29(29):S18.

Ford JM, Seiferheld W, Alger JR, Wu G, Endicott TJ, Mehta M, Curran W, Phan SC: Results of the phase I dose-escalating study of motexafin gadolinium with standard radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007,69(3):831–838. Epub 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.017

Curran WJ Jr, Scott CB, Horton J, Nelson JS, Weinstein AS, Fischbach AJ, Chang CH, Rotman M, Asbell SO, Krisch RE, et al.: Recursive partitioning analysis of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group malignant glioma trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993,85(9):704–710. 10.1093/jnci/85.9.704

Li J, Wang M, Won M, Shaw EG, Coughlin C, Curran WJ Jr, Mehta MP: Validation and simplification of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group recursive partitioning analysis classification for glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011,81(3):623–630. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.012

Jain RK: Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat Med 2003,9(6):685–693. 10.1038/nm0603-685

Osada H, Tokunaga T, Nishi M, Hatanaka H, Abe Y, Tsugu A, et al.: Overexpression of the neuropilin 1 (NRP1) gene correlated with poor prognosis in human glioma. Anti Cancer Res 2004, 24: 547–552.

Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, Mikkelsen T, Schiff D, Abrey LE, et al.: Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2009,27(28):4733–4740. 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721

Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, Duic P, Royce C, Stroud I, et al.: Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2009,27(5):740–745. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3055

Lai A, Tran A, Nghiemphu PL, Pope WB, Solis OE, Selch M, et al.: Phase II study of bevacizumab plus temozolomide during and after radiation therapy for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol 2011,29(2):142–148. 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2729

Martinez R, Schackert G, Yaya-Tur R, Rojas-Marcos I, Herman JG, Esteller M: Frequent hypermethylation of the DNA repair gene MGMT in long-term survivors of glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol 2007, 83: 91–93. 10.1007/s11060-006-9292-0

Esteller M, Garcia-Foncillas J, Andion E, Goodman SN, Hidalgo OF, Vanaclocha V, et al.: Inactivation of the DNA-repair gene MGMT and the clinical response of gliomas to alkylating agents. N Engl J Med 2000, 343: 1350–1354. 10.1056/NEJM200011093431901

Aldape K, Wang M, Sulman E, Hegi M, Colman H, Jones G, et al.: RTOG 0525: molecular correlates from a randomized phase III trial of newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29: S18. [Abstract] 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.9199

Reifenberger G, Hentschel B, Felsberg J, et al.: Predictive impact of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma of the elderly. Int J Cancer 2012, 131: 1342–1350. 10.1002/ijc.27385

Gallego Perez-Larraya J, Ducray F, Chinot O, et al.: Temozolomide in elderly patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma and poor performance status: an ANOCEF phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29: 3050–3055. 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8086

Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, NOA-08 Study Group of the Neuro-oncology Working Group (NOA) of the German Cancer Society, et al.: Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012, 13: 707–715. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70164-X

Malmstrom A, Grønberg BH, Marosi C, et al.: Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy for patients aged over 60 years with glioblastoma: the Nordic randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012. in press

Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, Forrest WF, Soriano RH, Wu TD, et al.: Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell 2006,9(3):157–173. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019

Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al.: Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 2010,17(1):98–110. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020

Acknowledgements

This trial was conducted by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG), and was supported by RTOG grant U10 CA21661 and CCOP grant U10 CA37422 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). This manuscript’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Financial support

RTOG grant U10 CA21661 and CCOP grant U10 CA37422 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dr. Mehta has served as a consultant for Merck, Roche, BMS, Novocure, Elekta, Phillips, Novelos and has stock optins in Accuray and Pharmacyclics.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to work and read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Krauze, A.V., Won, M., Graves, C. et al. Predictive value of tumor recurrence using urinary vascular endothelial factor levels in patients receiving radiation therapy for Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Biomark Res 1, 29 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7771-1-29

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7771-1-29