Abstract

This review evaluates the mechanism of volatile anesthetics as cardioprotective agents in both clinical and laboratory research and furthermore assesses possible cardiac side effects upon usage. Cardiac as well as non-cardiac surgery may evoke perioperative adverse events including: ischemia, diverse arrhythmias and reperfusion injury. As volatile anesthetics have cardiovascular effects that can lead to hypotension, clinicians may choose to administer alternative anesthetics to patients with coronary artery disease, particularly if the patient has severe preoperative ischemia or cardiovascular instability. Increasing preclinical evidence demonstrated that administration of inhaled anesthetics - before and during surgery - reduces the degree of ischemia and reperfusion injury to the heart. Recently, this preclinical data has been implemented clinically, and beneficial effects have been found in some studies of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Administration of volatile anesthetic gases was protective for patients undergoing cardiac surgery through manipulation of the potassium ATP (KATP) channel, mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, as well as through cytoprotective Akt and extracellular-signal kinases (ERK) pathways. However, as not all studies have demonstrated improved outcomes, the risks for undesirable hemodynamic effects must be weighed against the possible benefits of using volatile anesthetics as a means to provide cardiac protection in patients with coronary artery disease who are undergoing surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Volatile anesthetics (VA) are gases that are used to induce and maintain general anesthesia, with benefits of relatively rapid onset and recovery with acceptable effects on peripheral organs in most patients. In 1275 Spanish physician Raymond Lullus made a volatile liquid that he called “sweet vitriol”—diethyl ether—which was later used as an anesthetic. Years later, an American physician, Crawford W. Long, noticed that colleagues under the influence of ether felt no pain when they injured themselves. In 1842, Long conducted the first surgery with the use of ether as an anesthetic, his patient, undergoing removal of a tumor in his neck, did not report pain. Long published his report in 1849, after William T. G. Morton had performed the first public demonstration of successful ether anesthesia in the operating amphitheater of Massachusetts General Hospital on October 16, 1846 [1].

VA have been shown to offer benefits in a wide range of medical situations such as use in stroke victims by reducing the amount of ischemic injury during the event of stroke and delaying the development of brain injury [2, 3]; or as renal protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury—reducing plasma creatinine and reducing renal necrosis [4–9]. Some of these gases such as isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane have demonstrated cardioprotection by reducing or preventing myocardial ischemia both intraoperatively and postoperatively [10]. However, VA administration is associated with myocardial depression and vasodilation that can contribute to intraoperative hypotension, potentially upsetting the balance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand with resulting intraoperative myocardial ischemia [5]. Thus many clinicians choose to limit or avoid administration of VA to patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). For example nearly 40% of Italian heart surgery centers reported administration of VA to less than 25% of their CABG patients [11]. Similarly a meta-analysis found nearly half of patients were given total intravenous anesthesia in trials investigating VA effects during cardiac surgery [12]. Further, VA administration was found to be associated with worse outcome in the subset of cardiac surgery patients who had worse preoperative cardiac ischemia or cardiovascular instability [13]. Further, rapid induction of inhaled anesthesia can prolong the QT interval [14], which may be of concern in patients otherwise already at risk for ventricular fibrillation as may be seen during acute myocardial ischemia.

This review will focus on isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane as agents used to achieve cardioprotection emphasizing recent laboratory and clinical data on the use of inhaled anesthetics for cardioprotection. It also discusses the possible cardiac risks associated with inhaled anesthesia.

Literature search strategy

The literature search for this review focused on the volatile anesthetics isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane. The following search conditions were used for each volatile anesthetic: volatile anesthetic AND cardiovascular protection, OR cardiac ischemia, OR cardiac injury, OR cardiac toxicity, OR cardiac ischemic preconditioning, OR myocyte toxicity, OR myocyte ischemia, OR myocyte hypoxia, OR cardiac hemorrhage, OR cardiac tolerance, OR cardiac postconditioning, OR cardiac preconditioning, OR myocyte apoptosis, OR cardiac arrhythmias. Articles that were not available in English were excluded from the references. The available literature is discussed as related to key areas of cardioprotection research and clinical care.

Ischemic preconditioning

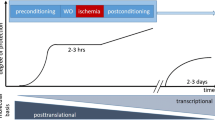

Ischemic injury is a pathological process that occurs when blood supply is interrupted to a specific area of tissue that occurs when oxygen (O2) demand exceeds O2 supply. In the event of ischemia, the myocardium continues to function by utilizing its stores of glycogen. However, if oxygen deprivation occurs for more than 15 minutes the myocardial tissue will become necrotic and lead to irreversible damage through tissue death [15]. Preconditioning is the process by which a certain level of injury is inflicted upon an organ or tissue, however this injury provides protection to the tissue in the event of a greater injurious process occurring. By inducing a short period of ischemia “cardiac myocytes reduce their contractile effort within a few seconds and stop contracting within the first few minutes” [16], which leads to energy conservation that helps protect myocardial tissue by reducing the amount of tissue necrosis. Cardiac ischemic preconditioning may lead to fatal consequences since impairment to the heart has immediate consequences to the rest of the body – leading to interruption of all organ system blood supplies which can result in brain damage, renal failure, pulmonary edema, etc. Clinical studies have shown that ischemic preconditioning reduces infarct size following induced myocardial ischemia [17–20]. This concept was first introduced in 1986 when Murry and colleagues demonstrated that ischemic preconditioning reduced infarct size in dogs from 29% in the control group to 7% in the group receiving ischemic preconditioning following coronary artery occlusion [20]. The dogs were subjected to brief periods of coronary artery occlusion (4-5 min) before an ischemic event consisting of a 40-min artery occlusion. The 22% reduction in infarct size observed by Murry et al. suggests that a protective mechanism underlies ischemic preconditioning.

Additional research has linked several intracellular signaling pathways to the phenomenon of ischemic preconditioning. The primary target in all of these pathways appears to be the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive K + (KATP) channel. KATP channels are located on mitochondrial, sarcolemmal and nuclear membranes of cardiomyocytes, and are also found in the brain, pancreatic β cells, skeletal and smooth muscle, and neurons [21]. The opening of mitochondrial KATP channels leads to generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), activating downstream kinases, resulting in cardioprotection [22] It has been shown that an initial increase in ROS leads to activation of the cytokine pathways such as protein kinase C (PKC) and tyrosine kinases (TK) which lead to opening of the mitochondrial KATP channels leading to a reduction in ROS. Thus an initial increase in ROS stimulated by ischemia leads to activation of pathways that result in reduction of ROS. In addition, activation and expression of KATP channels promotes action potential shortening and energy conservation, which is protective by preserving the cardiac tissue [23] Figure 1.

Reperfusion injury

Ischemic injury leads to reperfusion injury, when blood flow is restored to an ischemic area. The process of reperfusion leads to severe Ca2+ accumulation—due to cell membrane damage—that induces opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), which causes collapse of the mitochondrial membrane, uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in ATP depletion and cell death. Ischemia also leads to conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase in cardiomyocytes due to the lack of oxygen for metabolism. Xanthine oxidase leads to a build-up of hypoxanthine [24]. Upon reperfusion, xanthine oxidase metabolizes hypoxanthine, which leads to the overproduction of ROS. This phenomenon can cause already damaged tissue to produce superoxide radicals that further damage this tissue, leading to irreversible systolic dysfunction.

Volatile Anesthetics pretreatment

The administration of anesthetics activates or primes some of the same pathways that lead to protection from ischemic preconditioning. Zaugg et al. [25] verified that exposing cardiomyocytes to volatile anesthetic (isoflurane or sevoflurane) prior to myocardial ischemia decreased ischemic damage in a dose-dependent manner similar to the beneficial effect from ischemic preconditioning, Through administration of KATP blockers 5-HD (mitochondrial KATP blocker) and HMR-1098 (sarcolemmal KATP blocker) as well as a KATP activator, diazoxide, they were able to show that isoflurane and sevoflurane prime the mitochondrial KATP channel but do not affect the sarcolemmal KATP channels. Zaugg and colleagues explained that sevoflurane and isoflurane administration lead to activation of mitochondrial KATP channels as is similarly seen in ischemic pretreatment. This same research group showed that outcome following coronary artery bypass surgery was improved by sevoflurane compared to placebo pretreatment, reducing the incidence of late cardiac ischemic and congestive heart failure [26]. However, it is not clear that the effect from volatile anesthesia pretreatment is additive to occlusion-induced ischemic preconditioning [27]. Warltier et al. demonstrated better recovery of myocardial function after 15 minutes of coronary artery occlusion when VA were administered prior to occlusion [28]. In this experiment dogs were anesthetized with halothane or isoflurane and their myocardial function returned to baseline within 5 hours after reperfusion. Dogs that did not undergo pretreatment with anesthesia experienced a 50% decrease in myocardial function. Further research has demonstrated a similar type of cardioprotection from ischemia and myocardial dysfunction using sevoflurane, desflurane and enflurane [29–31]. Piriou et al. [31] in a study on rabbit myocardium showed that desflurane is the most protective VA in pretreatment for ischemic injury whereas sevoflurane had no significant effect, and pretreatment with halothane and isoflurane induced the same cardioprotective effect. However, in other models sevoflurane pretreatment provides cardioprotection [32–39]

Additional mechanisms have been elicited that appear to be involved in cardioprotection as a result of preconditioning. These mechanisms include the Akt, ROS, and ERK pathways [32, 34, 39–49] (Table 1). Channels that have been identified to be involved are: mPTP, sarcolemmal KATP channel, and the mitochondrial KATP channel [25, 33, 45, 48, 50–85] (Table 2).

Mechanistic pathways

Several key mechanistic pathways and regulators that have been identified as mediators in the protective effects of pretreatment with VAGs including KATP channel activation, mPTP modulation and the cytokine pathways (Akt/PI3K). KATP channels, established as cardioprotective mediators in ischemic preconditioning, have been studied in VA pretreatment. It has been shown that opening of the mitochondrial KATP channel leads to generation of ROS [22]. In a study utilizing rat trabeculae, de Ruijter et al. [48] demonstrated that the cardioprotective effect of sevoflurane occurs via the activation of PKC, which leads to mitochondrial KATP channel opening. Rat trabeculae underwent ischemia and then 60 minutes of reperfusion, and the recovery of active force was used as a measure of cardiac function following myocardial infarction (MI). Sevoflurane improved recovery of active force to 67% as opposed to 28% in the control group. However, when the KATP channel inhibitor (5-HD) was administered along with sevoflurane force recovery was only 31%, while the administration of a ROS scavenger and sevoflurane resulted in force recovery of only 33%. This data indicates that both the KATP channel and ROS are involved in the protective mechanisms of sevoflurane. According to Marinovic et al. [60] it appears that the sarcolemmal KATP channel is an effector of pretreatment whereas mitochondrial KATP channels are both a trigger and an effector. This was established when both mitochondrial and sarcolemmal KATP channel inhibitors were administered during isoflurane pretreatment in rat cardiomyocytes and a reduction in protection from the sevoflurane pretreated group was observed with 5-HD but not with HMR-1098. However, if HMR-1098 was applied throughout the experiment rather than during just pretreatment, the protective effect was abolished.

Piriou et al. [52] noted that the KATP channel is also linked to the mPTP. With this study it was suggested that both ischemic preconditioning and VA pretreatment delays mPTP opening. Delaying mPTP opening is protective because opening of the mPTP leads to swelling of the mitochondrial matrix, which causes collapse of the inner mitochondrial membrane, uncoupling of the electron transport chain, and release of cytochrome c along with other apoptotic factors such as Bax, caspase-9 and ATP. Administering 5-HD abolished the improved tolerance to calcium-induced mPTP opening. This demonstrates a likely connection between the mPTP and KATP channel.

Another pathway that has been identified clinically in cardioprotection is the Akt/PI3k pathway, which is a key intracellular signaling pathway in apoptosis. Raphael et al. [40] studied the role of the Akt/PI3K pathway in VA cardioprotection. Examination of DNA fragmentation conducted using the TUNEL method demonstrated that isoflurane pretreatment significantly reduced the percentage of apoptotic nuclei. Furthermore, evaluation of the Akt and phosphorylated-Akt (active Akt) expression during ischemia and reperfusion revealed that phosphorylated Akt was expressed in significantly higher numbers for the ischemia-reperfusion and isoflurane pretreated groups while administration of wortmannin and LY294002 (PI3K inhibitors) led to inhibition of phosphorylated Akt. Further, treatment with wortmannin and LY294002 abolished the cardioprotective effects of anesthetic pretreatment, indicating that phosphorylated Akt leads to cardioprotection.

The extracellular-signal kinases (ERK) pathway has been linked to myocardial protection elicited by pretreatment with VA. Toma et al. [86] studied ERK phosphorylation (activated form of ERK) that was induced by pretreatment with desflurane; rats were subjected to myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Administration of the MEK/ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 with desflurane eliminated cardioprotection that was observed in the desflurane-only pretreatment group. This points to MEK/ERK1/2 as modulators of the protective effects of VA administration prior to injury. Western blot analysis showed an early increase in ERK phosphorylation with the first administration of desflurane 10 minutes post-MI. However, this decreased with the second desflurane dose 25 minutes post-MI. Even though it has been shown that ERK1/2 is a downstream effector of PKC mediating effects it was discovered that ERK phosphorylation was not PKC dependent. Giving rats a dose of calphostin C (PKC inhibitor) did not affect the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 observed on Western blot. These results illustrate ERK1/2 activation as cardioprotective with a single dose of desflurane but this cardioprotection is diminished with an additional dose, highlighting the importance of administration protocols for VA pretreatment. Finally, it was indicated that ERK1/2 activation is independent on PKC.

In addition, Ca2+ flux has been linked to cardioprotection via VA pretreatment as well as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) involvement. An et al. [87] measured Ca2+ concentration by fluorescence and demonstrated that pretreatment with sevoflurane improved coronary blood flow and reduced systolic Ca2+ loading. Further, decreased destruction of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ − cycling proteins was observed on Western Blot. The reduced systolic Ca2+ leads to the conclusion that this is a cardioprotective effect since reperfusion injury—which leads to irreversible damage—is a result of Ca2+ excess. The accumulation of Ca2+ after ischemia-reperfusion leads to activation of NF-κB, which causes release of inflammatory mediators. Further research demonstrated preservation of calcium cycling proteins following VA pretreatment in a myocardial ischemia-reperfusion model [58]. Konia et al. [88] studied the inhibition of NF-κB in rats pretreated with sevoflurane; parthenolide (IF-κB inhibitor) was administered to prevent activation of NF-κB. It was concluded that inhibition of NF-κB leads to even greater protection from ischemia than sevoflurane administration alone; sevoflurane treatment group exhibited an infarct size of 19%, parthenolide group exhibited an infarct size of 18%, the sevoflurane + parthenolide group exhibited an infarct size of 10%, compared to the control groups with an infarct size of 59%. The involvement of NF-κB for anesthetic pretreatment needs to be further examined and directly linked to anesthesia pretreatment.

Clinical research

While anesthetic pretreatment demonstrates cardioprotection in the laboratory, it is crucial to answer the question whether these cardioprotective effects are also clinically applicable. Cardiac surgery is a suitable model for studying VA pretreatment, however the administration of other anesthetics during the cardiac surgery may also provide protection, leading to difficulty of clearly answering the question of whether VA are cardioprotective clinically. Clinical trials have evaluated VA pretreatment on patients undergoing cardiac surgery - especially CABG, some of which support a beneficial effect of VA for decreasing myocardial infarction, troponin release, hospital length of stay and death [12, 89, 90].For example, in studies involving CABG patients, Guarracino et al. [91] and Meco et al. [92] (Meco 2007) found that desflurane administration was associated with lesser postoperative elevation of biochemical markers of myocardial injury than total intravenous anesthesia. In contrast, De Hert et al. did not find a difference in postoperative biochemical markers of myocardial injury in patients given desflurane or sevoflurane compared to those receiving total intravenous anesthesia. However, patients given either VA had shorter hospital length of stay and lower 1-year mortality [93]. In a retrospective study including over 10,000 cardiac surgery patients, VA administration was associated with better outcomes in patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery. However, in patients with severe preoperative myocardial ischemia or cardiovascular instability, the administration of VA was associated with worse outcome than the administration of total intravenous anesthesia [13]. Added evidence to support a benefit to the use of VA in cardiac surgery was reported by Bignami et al. [11] who found better outcomes following cardiac surgery in centers in which cardiac surgery patients are given VA. This analysis suggested the benefit was greater when VA are given for a greater portion of the procedure. Amr et al. found both ischemic preconditioning and isoflurane preconditioning were associated with better cardioprotection than cold blood cardioplegia in CABG patients anesthetized with total intravenous anesthesia [94]. Further evidence to support a beneficial effect of VA administration to CABG patients is that remote ischemic preconditioning was associated with benefit in patients anesthetized with VA but not in those given propofol for anesthesia [95]. An international consensus conference provided expert opinion support for the use of VA in hemodynamically stable cardiac surgery patients [96] as a means to reduce myocardial damage and death. This consensus concluded that the further large randomized controlled trials of VA administration to cardiac surgery patients are necessary.

Several studies have used human cardiac tissue to examine the benefits of VA pretreatment as well as to identify similar mechanistic pathways involved to those elicited in animal studies. Some key mechanistic pathways have been examined using drugs that antagonize ion channels and pathways involved in anesthesia pretreatment. Jiang et al. [42] used human ventricular muscle cell not suitable for donor transplantation, to examine the presence of mitochondrial KATP channel activity in human tissue. By providing a dose of 5-HD to cells it was demonstrated that modulation of the mitochondrial KATP channel is involved in human as well as animal cardiomyocytes during ischemic injury. Administration of 5-HD reduced mitochondrial KATP channel activity in the treatment group. In another group, isoflurane increased mitochondrial KATP channel activity and increased peak current beyond that of the control group demonstrating the role of KATP channel in VA pretreatment clinically. Further clinical studies have shown that ROS are involved in cardioprotection from anesthetic pretreatment; therefore, they investigated the effects of exogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in their apparatus. First, a cluster of mitochondrial KATP channels were suppressed by ATP administration, next H2O2 was given which resulted in a reactivation of the KATP channels despite the continued presence of ATP indicating that ROS influences KATP channels in human myocardium, in vitro.

In an in vitro study using right atrial appendages obtained from adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery, Mio et al. [55] explored the mechanistic effects of VA pretreatment. They suggested that KATP channels are involved in cardioprotection from pretreatment with volatile anesthetics, as their results demonstrated isoflurane decreased stress-induced cell death and maintained mitochondrial function. Isoflurane preserved mitochondrial oxygen consumption which was initiated by pyruvate-malate and accelerated by adenosine diphosphate (ADP). Preservation of mitochondrial oxygen consumption indicates a cardioprotective effect from isoflurane. In addition, they noted that isoflurane was protective via the sarcolemmal KATP mechanism. Administration of HMR-1098 diminished the cardioprotective effect of isoflurane from a cell death percentage of 21% (without HMR-1098) to a cell death percentage of 41% with HMR-1098 indicating the involvement of KATP channel clinically.

Hanouz et al. [34] studied the role of ROS in cardioprotection from pretreatment with sevoflurane and desflurane by using in vitro human right atrial trabeculae. Recovery of force of contraction was studied in each experimental group: control, sevoflurane pretreatment, and desflurane pretreatment. Force of contraction recovery was significantly improved in the sevoflurane group (from 53% to 85%) and in the desflurane group (from 53% to 86%). Treatment with MPG (ROS scavenger) prevented the force of contraction recovery: in the desflurane + MPG group, force of contraction changed from 53% to 48% and in the sevoflurane + MPG group force of contraction changed from 53% to 56% (both the same as control). Since the administration of MPG abolished recovery in both the desflurane and sevoflurane groups, they concluded that ROS must play a role in the cardioprotective mechanisms triggered by VA pretreatment. The mechanistic pathways of cardioprotection in human tissue has been evaluated through in vitro studies, however further in vivo studies are necessary to definitively establish VA pretreatment as a treatment option for cardioprotection in patients at-risk for myocardial ischemia.

Cardiac side effects of medical gas anesthesia

All VA have clinically relevant myocardial depressant effects when given in usual anesthetic concentrations [97]. These effects may contribute to the cardioprotective effects of VA, but must be considered when administering VA to patients with significant cardiac dysfunction. In addition to myocardial depressant effects, VA administered in clinically relevant concentrations cause vasodilation, which can contribute to hemodynamic instability when given to patients with ischemic cardiac disease. Additionally, several studies have demonstrated that administration of VA may lead to prolongation of the QT interval [98–105]. This is concerning because a prolonged QT interval increases the risk for arrhythmia development. The QT interval is the portion on an electrocardiogram representing the portion of the cardiac electrical cycle in which both depolarization and repolarization of the ventricles occur. Prolonging the length of this interval increases a patient’s risk for torsades de pointes, which may lead to ventricular fibrillation [106, 107] as has been reported during anesthetics with VA [108–110]. Despite this, VA use has been reported as safe in patients with known long QT syndrome [111, 112]. Furthermore, even though studies have demonstrated that VA administration prolongs the QT interval, ventricular arrhythmia incidence was lower in the subset of 10,535 CABG patients who were given sevoflurane compared to those given propofol for anesthesia [13]. Other studies of patients undergoing CABG did not report an increase in ventricular arrhythmias following pretreatment with VA [4, 26, 113]. Further, animal studies show that VA pre- or post-conditioning provides an antiarrhythmic effect [114–116]. However, in patients whose medical condition may predispose to cardiac dysrhythmia or hemodynamic instability, such as those with severe preoperative myocardial ischemia, it is reasonable to use greater caution when administering VA for cardiac protection (Table 3).

Lack of cardioprotection?

Zangrillo et al. [117] recently demonstrated that no cardioprotection exists with pretreatment of VA in non-cardiac surgeries. This study suggests that non-cardiac surgery patients do not receive any reduction in release of troponin postoperatively (myocardial injury marker). Similarly, Piriou et al. [118] did not find significant effects of VA in a randomized trial of patients undergoing CABG, while De Hert et al. [93] in a multicenter randomized trial studying over 400 patients found no differences in markers of cardiac damage following CABG in patients given VA compared to intravenous anesthesia. Bignami et al. did not find benefit from sevoflurane administration to patients with known coronary artery disease who were undergoing mitral valve surgery [119]. A meta-analysis of studies enrolling over 6,200 patients undergoing noncardiac surgery did not find myocardial infarction or death in the studies reviewed, which limited analysis of choice of anesthetic technique impact on clinically relevant outcomes [120]. However, Bassuoni et al. reported a beneficial effect of VA administration compared to propofol anesthesia [121]. They found VA administration was associated with less myocardial ischemia and troponin release after noncardiac peripheral vascular surgery in a study of 126 patients who did not have significant additional comorbid conditions.Recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines that state that patients at risk for myocardial infarction during non-cardiac surgery would benefit from pretreatment with gas anesthesia, if hemodynamically stable [122].

Conclusion and future direction

Abounding evidence has shown that pretreatment with volatile anesthetics protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in both animal and clinical studies. Future investigations need to evaluate the most optimal anesthetic agent, concentration and administration protocol for the best cardioprotective benefits of pretreatment, as studies have noted that there is a difference in cardioprotection dependent upon pretreatment protocol with VA [11]. Additionally, a comprehensive mechanistic model needs to be elicited that integrates all mechanisms evaluated thus far. Several other players in the mechanism of cardioprotection have been examined. However, further studies are needed to confirm these mechanisms, which include: caveolin [123], caspase [124], Pim-1 kinase [125], β-adrenergic [126], and coronary vasodilation [127, 128].

We conclude the results of laboratory studies provide mechanistic pathways supporting the cardioprotective effect of pretreatment with VA. Our opinion is these effects should be beneficial to patients with ischemic cardiac disease who are undergoing surgery. However, the optimum dose and timing of VA administration for this effect must be further investigated. It is reasonable to use greater caution when administering VA for cardiac protection to patients in whom preoperative hemodynamic conditions or cardiac rhythm would magnify the known side effects of VA (vasodilation, cardiac depression or QT prolongation).

Abbreviations

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate -sensitive K + (KATP) channel

- mPTP:

-

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- VA:

-

Volatile anesthetics

- O2:

-

Oxygen

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- PKC:

-

Protein kinase C

- TK:

-

Tyrosine kinase

- FoC:

-

Recovery of force of contraction

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- ERK:

-

Extracellular-signal kinases (ERK) pathway

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor-κB

- CABG:

-

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

- H2O2:

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- ADP:

-

Adenosine diphosphate

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram.

References

Whalen FX, Bacon DR, Smith HM: Inhaled anesthetics: an historical overview. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2005, 19 (3): 323-330.

Yung LM, Wei Y, Qin T, Wang Y, Smith CD, Waeber C: Sphingosine kinase 2 mediates cerebral preconditioning and protects the mouse brain against ischemic injury. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012, 43 (1): 199-204.

Altay O, Hasegawa Y, Sherchan P, Suzuki H, Khatibi NH, Tang J, Zhang JH: Isoflurane delays the development of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage through sphingosine-related pathway activation in mice. Crit Care Med. 2012, 40: 1908-1913.

Julier K, da Silva R, Garcia C, Bestmann L, Frascarolo P, Zollinger A, Chassot PG, Schmid ER, Turina MI, von Segesser LK, Pasch T, Spahn DR, Zaugg M: Preconditioning by sevoflurane decreases biochemical markers for myocardial and renal dysfunction in coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Anesthesiology. 2003, 98 (6): 1315-1327.

Lee HT, Kim M, Song JH, Chen SW, Gubitosa G, Emala CW: Sevoflurane-mediated TGF-beta1 signaling in renal proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008, 294 (2): F371-F378.

Kim M, Kim M, Kim N, D'Agati VD, Emala CW, Lee HT: Isoflurane mediates protection from renal ischemia-reperfusion injury via sphingosine kinase and sphingosine-1-phosphate-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007, 293 (6): F1827-F1835.

Kim M, Kim M, Park SW, Pitson SM, Lee HT: Isoflurane protects human kidney proximal tubule cells against necrosis via sphingosine kinase and sphingosine-1-phosphate generation. Am J Nephrol. 2010, 31 (4): 353-362.

Lee HT, Kim M, Kim J, Kim N, Emala CW: TGF-beta1 release by volatile anesthetics mediates protection against renal proximal tubule cell necrosis. Am J Nephrol. 2007, 27 (4): 416-424.

Lee HT, Kim M, Jan M, Emala CW: Anti-inflammatory and antinecrotic effects of the volatile anesthetic sevoflurane in kidney proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006, 291 (1): F67-F78.

Warltier DCPP, Kersten JR: Approaches to the prevention of perioperative myocardial ischemia. Anesthesiology. 2000, 9: 253-

Bignami E, Biondi-Zoccai G, Landoni G, Fochi O, Testa V, Sheiban I, Giunta F, Zangrillo A: Volatile anesthetics reduce mortality in cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009, 23 (5): 594-599.

Landoni G, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Zangrillo A, Bignami E, D'Avolio S, Marchetti C, Calabro MG, Fochi O, Guarracino F, De Tritapepe L, Hert S, Torri G: Desflurane and sevoflurane in cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007, 21 (4): 502-511.

Jakobsen CJ, Berg H, Hindsholm KB, Faddy N, Sloth E: The influence of propofol versus sevoflurane anesthesia on outcome in 10,535 cardiac surgical procedures. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007, 21 (5): 664-671.

Omek EOD, Alkent ZP, Ekin A, Basaran M, Dikmen B: The effects of volatile induction and maintenance of anesthesia and selective spinal anesthesia on QT interval, QT dispersion, and arrhythmia incidence. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010, 65 (8): 763-7.

Sanada S, Komuro I, Kitakaze M: Pathophysiology of myocardial reperfusion injury: preconditioning, postconditioning, and translational aspects of protective measures. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011, 301 (5): H1723-H1741.

De Hert SG, Turani F, Mathur S, Stowe DF: Cardioprotection with volatile anesthetics: mechanisms and clinical implications. Anesth Analg. 2005, 100 (6): 1584-1593.

Heusch G, Schulz R: The biology of myocardial hibernation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000, 10 (3): 108-114.

Kloner RA, Jennings RB: Consequences of brief ischemia: stunning, preconditioning, and their clinical implications: part 2. Circulation. 2001, 104 (25): 3158-3167.

Kloner RA, Jennings RB: Consequences of brief ischemia: stunning, preconditioning, and their clinical implications: part 1. Circulation. 2001, 104 (24): 2981-2989.

Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA: Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986, 74 (5): 1124-1136.

Zhuo ML, Huang Y, Liu DP, Liang CC: KATP channel: relation with cell metabolism and role in the cardiovascular system. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005, 37 (4): 751-764.

Oldenburg O, Cohen MV, Yellon DM, Downey JM: Mitochondrial K(ATP) channels: role in cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2002, 55 (3): 429-437.

Zingman LV, Zhu Z, Sierra A, Stepniak E, Burnett CM, Maksymov G, Anderson ME, Coetzee WA, Hodgson-Zingman DM: Exercise-induced expression of cardiac ATP-sensitive potassium channels promotes action potential shortening and energy conservation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011, 51 (1): 72-81.

Thompson-Gorman SL, Zweier JL: Evaluation of the role of xanthine oxidase in myocardial reperfusion injury. J Biol Chem. 1990, 265 (12): 6656-6663.

Zaugg M, Lucchinetti E, Spahn DR, Pasch T, Schaub MC: Volatile anesthetics mimic cardiac preconditioning by priming the activation of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels via multiple signaling pathways. Anesthesiology. 2002, 97 (1): 4-14.

Garcia C, Julier K, Bestmann L, Zollinger A, von Segesser LK, Pasch T, Spahn DR, Zaugg M: Preconditioning with sevoflurane decreases PECAM-1 expression and improves one-year cardiovascular outcome in coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2005, 94 (2): 159-165.

Lucchinetti E, Bestmann L, Feng J, Freidank H, Clanachan AS, Finegan BA, Zaugg M: Remote ischemic preconditioning applied during isoflurane inhalation provides no benefit to the myocardium of patients undergoing on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: lack of synergy or evidence of antagonism in cardioprotection?. Anesthesiology. 2012, 116 (2): 296-310.

Warltier DC, al-Wathiqui MH, Kampine JP, Schmeling WT: Recovery of contractile function of stunned myocardium in chronically instrumented dogs is enhanced by halothane or isoflurane. Anesthesiology. 1988, 69 (4): 552-565.

Takahata O, Ichihara K, Ogawa H: Effects of sevoflurane on ischaemic myocardium in dogs. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1995, 39 (4): 449-456.

Oguchi T, Kashimoto S, Yamaguchi T, Nakamura T, Kumazawa T: Comparative effects of halothane, enflurane, isoflurane and sevoflurane on function and metabolism in the ischaemic rat heart. Br J Anaesth. 1995, 74 (5): 569-575.

Piriou V, Chiari P, Lhuillier F, Bastien O, Loufoua J, Raisky O, David JS, Ovize M, Lehot JJ: Pharmacological preconditioning: comparison of desflurane, sevoflurane, isoflurane and halothane in rabbit myocardium. Br J Anaesth. 2002, 89 (3): 486-491.

Lamberts RR, Onderwater G, Hamdani N, Vreden MJ, Steenhuisen J, Eringa EC, Loer SA, Stienen GJ, Bouwman RA: Reactive oxygen species-induced stimulation of 5'AMP-activated protein kinase mediates sevoflurane-induced cardioprotection. Circulation. 2009, 120 (11 Suppl): S10-S15.

Kaneda K, Miyamae M, Sugioka S, Okusa C, Inamura Y, Domae N, Kotani J, Figueredo VM: Sevoflurane enhances ethanol-induced cardiac preconditioning through modulation of protein kinase C, mitochondrial KATP channels, and nitric oxide synthase, in guinea pig hearts. Anesth Analg. 2008, 106 (1): 9-16.

Hanouz JL, Zhu L, Lemoine S, Durand C, Lepage O, Massetti M, Khayat A, Plaud B, Gerard JL: Reactive oxygen species mediate sevoflurane- and desflurane-induced preconditioning in isolated human right atria in vitro. Anesth Analg. 2007, 105 (6): 1534-1539.

Onishi A, Miyamae M, Kaneda K, Kotani J, Figueredo VM: Direct evidence for inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening by sevoflurane preconditioning in cardiomyocytes: comparison with cyclosporine A. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012, 675 (1–3): 40-46.

Lu X, Moore PG, Liu H, Schaefer S: Phosphorylation of ARC is a critical element in the antiapoptotic effect of anesthetic preconditioning. Anesth Analg. 2011, 112 (3): 525-531.

Tosaka S, Tosaka R, Matsumoto S, Maekawa T, Cho S, Sumikawa K: Roles of cyclooxygenase 2 in sevoflurane- and olprinone-induced early phase of preconditioning and postconditioning against myocardial infarction in rat hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011, 16 (1): 72-78.

Fradorf J, Huhn R, Weber NC, Ebel D, Wingert N, Preckel B, Toma O, Schlack W, Hollmann MW: Sevoflurane-induced preconditioning: impact of protocol and aprotinin administration on infarct size and endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation in the rat heart in vivo. Anesthesiology. 2010, 113 (6): 1289-1298.

Sedlic F, Pravdic D, Ljubkovic M, Marinovic J, Stadnicka A, Bosnjak ZJ: Differences in production of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial uncoupling as events in the preconditioning signaling cascade between desflurane and sevoflurane. Anesth Analg. 2009, 109 (2): 405-411.

Raphael J, Abedat S, Rivo J, Meir K, Beeri R, Pugatsch T, Zuo Z, Gozal Y: Volatile anesthetic preconditioning attenuates myocardial apoptosis in rabbits after regional ischemia and reperfusion via Akt signaling and modulation of Bcl-2 family proteins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006, 318 (1): 186-194.

Jamnicki-Abegg M, Weihrauch D, Pagel PS, Kersten JR, Bosnjak ZJ, Warltier DC, Bienengraeber MW: Isoflurane inhibits cardiac myocyte apoptosis during oxidative and inflammatory stress by activating Akt and enhancing Bcl-2 expression. Anesthesiology. 2005, 103 (5): 1006-1014.

Jiang MT, Nakae Y, Ljubkovic M, Kwok WM, Stowe DF, Bosnjak ZJ: Isoflurane activates human cardiac mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-sensitive K + channels reconstituted in lipid bilayers. Anesth Analg. 2007, 105 (4): 926-932.

Bouwman RA, Salic K, Padding FG, Eringa EC, van Beek-Harmsen BJ, Matsuda T, Baba A, Musters RJ, Paulus WJ, de Lange JJ, Boer C: Cardioprotection via activation of protein kinase C-delta depends on modulation of the reverse mode of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Circulation. 2006, 114 (1 Suppl): I226-I232.

Riess ML, Kevin LG, McCormick J, Jiang MT, Rhodes SS, Stowe DF: Anesthetic preconditioning: the role of free radicals in sevoflurane-induced attenuation of mitochondrial electron transport in Guinea pig isolated hearts. Anesth Analg. 2005, 100 (1): 46-53.

An J, Stadnicka A, Kwok WM, Bosnjak ZJ: Contribution of reactive oxygen species to isoflurane-induced sensitization of cardiac sarcolemmal adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel to pinacidil. Anesthesiology. 2004, 100 (3): 575-580.

Dworschak M, Breukelmann D, Hannon JD: Isoflurane applied during ischemia enhances intracellular calcium accumulation in ventricular myocytes in part by reactive oxygen species. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004, 48 (6): 716-721.

Novalija E, Kevin LG, Camara AK, Bosnjak ZJ, Kampine JP, Stowe DF: Reactive oxygen species precede the epsilon isoform of protein kinase C in the anesthetic preconditioning signaling cascade. Anesthesiology. 2003, 99 (2): 421-428.

de Ruijter W, Musters RJ, Boer C, Stienen GJ, Simonides WS, de Lange JJ: The cardioprotective effect of sevoflurane depends on protein kinase C activation, opening of mitochondrial K(+)(ATP) channels, and the production of reactive oxygen species. Anesth Analg. 2003, 97 (5): 1370-1376.

Novalija E, Varadarajan SG, Camara AK, An J, Chen Q, Riess ML, Hogg N, Stowe DF: Anesthetic preconditioning: triggering role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in isolated hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002, 283 (1): H44-H52.

Pravdic D, Mio Y, Sedlic F, Pratt PF, Warltier DC, Bosnjak ZJ, Bienengraeber M: Isoflurane protects cardiomyocytes and mitochondria by immediate and cytosol-independent action at reperfusion. Br J Pharmacol. 2010, 160 (2): 220-232.

Sedlic F, Sepac A, Pravdic D, Camara AK, Bienengraeber M, Brzezinska AK, Wakatsuki T, Bosnjak ZJ: Mitochondrial depolarization underlies delay in permeability transition by preconditioning with isoflurane: roles of ROS and Ca2+. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010, 299 (2): C506-C515.

Piriou V, Chiari P, Gateau-Roesch O, Argaud L, Muntean D, Salles D, Loufouat J, Gueugniaud PY, Lehot JJ, Ovize M: Desflurane-induced preconditioning alters calcium-induced mitochondrial permeability transition. Anesthesiology. 2004, 100 (3): 581-588.

Hirose K, Tsutsumi YM, Tsutsumi R, Shono M, Katayama E, Kinoshita M, Tanaka K, Oshita S: Role of the O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine in the cardioprotection induced by isoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2011, 115 (5): 955-962.

Zhu J, Rebecchi MJ, Tan M, Glass PS, Brink PR, Liu L: Age-associated differences in activation of Akt/GSK-3beta signaling pathways and inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening in the rat heart. J Gerontol Ser A, Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010, 65 (6): 611-619.

Mio Y, Bienengraeber MW, Marinovic J, Gutterman DD, Rakic M, Bosnjak ZJ, Stadnicka A: Age-related attenuation of isoflurane preconditioning in human atrial cardiomyocytes: roles for mitochondrial respiration and sarcolemmal adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel activity. Anesthesiology. 2008, 108 (4): 612-620.

Chen CH, Liu K, Chan JY: Anesthetic preconditioning confers acute cardioprotection via up-regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase and preservation of mitochondrial respiratory enzyme activity. Shock. 2008, 29 (2): 300-308.

Finegan BA, Gandhi M, Cohen MR, Legatt D, Clanachan AS: Isoflurane alters energy substrate metabolism to preserve mechanical function in isolated rat hearts following prolonged no-flow hypothermic storage. Anesthesiology. 2003, 98 (2): 379-386.

An J, Bosnjak ZJ, Jiang MT: Myocardial protection by isoflurane preconditioning preserves Ca2+ cycling proteins independent of sarcolemmal and mitochondrial KATP channels. Anesth Analg. 2007, 105 (5): 1207-1213.

Masui K, Kashimoto S, Furuya A, Oguchi T: Isoflurane and sevoflurane during reperfusion prevent recovery from ischaemia in mitochondrial KATP channel blocker pretreated hearts. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006, 23 (2): 123-129.

Marinovic J, Bosnjak ZJ, Stadnicka A: Distinct roles for sarcolemmal and mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels in isoflurane-induced protection against oxidative stress. Anesthesiology. 2006, 105 (1): 98-104.

Stadnicka A, Marinovic J, Bienengraeber M, Bosnjak ZJ: Impact of in vivo preconditioning by isoflurane on adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels in the rat heart: lasting modulation of nucleotide sensitivity during early memory period. Anesthesiology. 2006, 104 (3): 503-510.

Bouwman RA, van't Hof FN, de Ruijter W, van Beek-Harmsen BJ, Musters RJ, de Lange JJ, Boer C: The mechanism of sevoflurane-induced cardioprotection is independent of the applied ischaemic stimulus in rat trabeculae. Br J Anaesth. 2006, 97 (3): 307-314.

Obal D, Dettwiler S, Favoccia C, Scharbatke H, Preckel B, Schlack W: The influence of mitochondrial KATP-channels in the cardioprotection of preconditioning and postconditioning by sevoflurane in the rat in vivo. Anesth Analg. 2005, 101 (5): 1252-1260.

Marinovic J, Bosnjak ZJ, Stadnicka A: Preconditioning by isoflurane induces lasting sensitization of the cardiac sarcolemmal adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel by a protein kinase C-delta-mediated mechanism. Anesthesiology. 2005, 103 (3): 540-547.

An J, Camara AK, Riess ML, Rhodes SS, Varadarajan SG, Stowe DF: Improved mitochondrial bioenergetics by anesthetic preconditioning during and after 2 hours of 27 degrees C ischemia in isolated hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005, 46 (3): 280-287.

Aizawa K, Turner LA, Weihrauch D, Bosnjak ZJ, Kwok WM: Protein kinase C-epsilon primes the cardiac sarcolemmal adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel to modulation by isoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2004, 101 (2): 381-389.

Wakeno-Takahashi M, Otani H, Nakao S, Uchiyama Y, Imamura H, Shingu K: Adenosine and a nitric oxide donor enhances cardioprotection by preconditioning with isoflurane through mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-sensitive K + channel-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Anesthesiology. 2004, 100 (3): 515-524.

Stadnicka A, Bosnjak ZJ: Isoflurane decreases ATP sensitivity of guinea pig cardiac sarcolemmal KATP channel at reduced intracellular pH. Anesthesiology. 2003, 98 (2): 396-403.

Kevin LG, Novalija E, Riess ML, Camara AK, Rhodes SS, Stowe DF: Sevoflurane exposure generates superoxide but leads to decreased superoxide during ischemia and reperfusion in isolated hearts. Anesth Analg. 2003, 96 (4): 949-955.

Patel HH, Ludwig LM, Fryer RM, Hsu AK, Warltier DC, Gross GJ: Delta opioid agonists and volatile anesthetics facilitate cardioprotection via potentiation of K(ATP) channel opening. FASEB J. 2002, 16 (11): 1468-1470.

Kwok WM, Martinelli AT, Fujimoto K, Suzuki A, Stadnicka A, Bosnjak ZJ: Differential modulation of the cardiac adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channel by isoflurane and halothane. Anesthesiology. 2002, 97 (1): 50-56.

Fujimoto K, Bosnjak ZJ, Kwok WM: Isoflurane-induced facilitation of the cardiac sarcolemmal K(ATP) channel. Anesthesiology. 2002, 97 (1): 57-65.

Stadnicka A, Kwok WM, Warltier DC, Bosnjak ZJ: Protein tyrosine kinase-dependent modulation of isoflurane effects on cardiac sarcolemmal K(ATP) channel. Anesthesiology. 2002, 97 (5): 1198-1208.

Yamaguchi T, Kashimoto S, Oguchi T, Kumazawa T: Glyburide prevents isoflurane's reducing effects on hydroxyl radical formation in the postischemic reperfused rat heart. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2002, 7 (1): 25-29.

Hanouz JL, Yvon A, Massetti M, Lepage O, Babatasi G, Khayat A, Bricard H, Gerard JL: Mechanisms of desflurane-induced preconditioning in isolated human right atria in vitro. Anesthesiology. 2002, 97 (1): 33-41.

Chen Q, Camara AK, An J, Novalija E, Riess ML, Stowe DF: Sevoflurane preconditioning before moderate hypothermic ischemia protects against cytosolic [Ca(2+)] loading and myocardial damage in part via mitochondrial K(ATP) channels. Anesthesiology. 2002, 97 (4): 912-920.

Tonkovic-Capin M, Gross GJ, Bosnjak ZJ, Tweddell JS, Fitzpatrick CM, Baker JE: Delayed cardioprotection by isoflurane: role of K(ATP) channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002, 283 (1): H61-H68.

Shimizu J, Sakamoto A, Ogawa R: Activation of the adenosine triphosphate sensitive mitochondrial potassium channel is involved in the cardioprotective effect of isoflurane. J Nihon Med Sch. 2001, 68 (3): 238-245.

Hara T, Tomiyasu S, Sungsam C, Fukusaki M, Sumikawa K: Sevoflurane protects stunned myocardium through activation of mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Anesth Analg. 2001, 92 (5): 1139-1145.

Roscoe AK, Christensen JD, Lynch C: Isoflurane, but not halothane, induces protection of human myocardium via adenosine A1 receptors and adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Anesthesiology. 2000, 92 (6): 1692-1701.

Coetzee JF, le Roux PJ, Genade S, Lochner A: Reduction of postischemic contractile dysfunction of the isolated rat heart by sevoflurane: comparison with halothane. Anesth Analg. 2000, 90 (5): 1089-1097.

Tomai F, De Paulis R, Penta de Peppo A, Colagrande L, Caprara E, Polisca P, De Matteis G, Ghini AS, Forlani S, Colella D, Chiariello L: Beneficial impact of isoflurane during coronary bypass surgery on troponin I release. G Ital Cardiol. 1999, 29 (9): 1007-1014.

Mathur S, Farhangkhgoee P, Karmazyn M: Cardioprotective effects of propofol and sevoflurane in ischemic and reperfused rat hearts: role of K(ATP) channels and interaction with the sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibitor HOE 642 (cariporide). Anesthesiology. 1999, 91 (5): 1349-1360.

Kersten JR, Schmeling TJ, Hettrick DA, Pagel PS, Gross GJ, Warltier DC: Mechanism of myocardial protection by isoflurane. Role of adenosine triphosphate-regulated potassium (KATP) channels. Anesthesiology. 1996, 85 (4): 794-807.

Nakayama M, Fujita S, Kanaya N, Tsuchida H, Namiki A: Blockade of ATP-sensitive K + channel abolishes the anti-ischemic effects of isoflurane in dog hearts. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997, 41 (4): 531-535.

Toma O, Weber NC, Wolter JI, Obal D, Preckel B, Schlack W: Desflurane preconditioning induces time-dependent activation of protein kinase C epsilon and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 in the rat heart in vivo. Anesthesiology. 2004, 101 (6): 1372-1380.

An J, Rhodes SS, Jiang MT, Bosnjak ZJ, Tian M, Stowe DF: Anesthetic preconditioning enhances Ca2+ handling and mechanical and metabolic function elicited by Na + −Ca2+ exchange inhibition in isolated hearts. Anesthesiology. 2006, 105 (3): 541-549.

Konia MR, Schaefer S, Liu H: Nuclear factor-[kappa]B inhibition provides additional protection against ischaemia/reperfusion injury in delayed sevoflurane preconditioning. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009, 26 (6): 496-503.

Yu CH, Beattie WS: The effects of volatile anesthetics on cardiac ischemic complications and mortality in CABG: a meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2006, 53 (9): 906-918.

Landoni G, Bignami E, Oliviero F, Zangrillo A: Halogenated anaesthetics and cardiac protection in cardiac and non-cardiac anaesthesia. Ann Card Anaesth. 2009, 12 (1): 4-9.

Guarracino F, Landoni G, Tritapepe L, Pompei F, Leoni A, Aletti G, Scandroglio AM, Maselli D, De Luca M, Marchetti C, Crescenzi G, Zangrillo A: Myocardial damage prevented by volatile anesthetics: a multicenter randomized controlled study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006, 20 (4): 477-483.

Meco M, Cirri S, Gallazzi C, Magnani G, Cosseta D: Desflurane preconditioning in coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a double-blinded, randomised and placebo-controlled study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007, 32 (2): 319-325.

De Hert S, Vlasselaers D, Barbe R, Ory JP, Dekegel D, Donnadonni R, Demeere JL, Mulier J, Wouters P: A comparison of volatile and non volatile agents for cardioprotection during on-pump coronary surgery. Anaesthesia. 2009, 64 (9): 953-960.

Amr YM, Yassin IM: Cardiac protection during on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: ischemic versus isoflurane preconditioning. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010, 14 (3): 205-211.

Kottenberg E, Thielmann M, Bergmann L, Heine T, Jakob H, Heusch G, Peters J: Protection by remote ischemic preconditioning during coronary artery bypass graft surgery with isoflurane but not propofol - a clinical trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012, 56 (1): 30-38.

Landoni G, Augoustides JG, Guarracino F, Santini F, Ponschab M, Pasero D, Rodseth RN, Biondi-Zoccai G, Silvay G, Salvi L, Camporesi E, Comis M, Conte M, Bevilacqua S, Cabrini L, Cariello C, Caramelli F, De Santis V, Del Sarto P, Dini D, Forti A, Galdieri N, Giordano G, Gottin L, Greco M, Maglioni E, Mantovani L, Manzato A, Meli M, Paternoster G: Mortality reduction in cardiac anesthesia and intensive care: results of the first International Consensus Conference. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2011, 55 (3): 259-266.

De Hert SG: Volatile anesthetics and cardiac function. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006, 10 (1): 33-42.

Hanci V, Aydin M, Yurtlu BS, Ayoglu H, Okyay RD, Tas E, Erdogan G, Aydogan K, Turan IO: Anesthesia induction with sevoflurane and propofol: evaluation of P-wave dispersion, QT and corrected QT intervals. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2010, 26 (9): 470-477.

Han DW, Park K, Jang SB, Kern SE: Modeling the effect of sevoflurane on corrected QT prolongation: a pharmacodynamic analysis. Anesthesiology. 2010, 113 (4): 806-811.

Nakao S, Hatano K, Sumi C, Masuzawa M, Sakamoto S, Ikeda S, Shingu K: Sevoflurane causes greater QTc interval prolongation in elderly patients than in younger patients. Anesth Analg. 2010, 110 (3): 775-779.

Kazanci D, Unver S, Karadeniz U, Iyican D, Koruk S, Yilmaz MB, Erdemli O: A comparison of the effects of desflurane, sevoflurane and propofol on QT, QTc, and P dispersion on ECG. Ann Card Anaesth. 2009, 12 (2): 107-112.

Aypar E, Karagoz AH, Ozer S, Celiker A, Ocal T: The effects of sevoflurane and desflurane anesthesia on QTc interval and cardiac rhythm in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007, 17 (6): 563-567.

Kang J, Chen XL, Reynolds WP, Rampe D: Functional interaction between DPI 201–106, a drug that mimics congenital long QT syndrome, and sevoflurane on the guinea-pig cardiac action potential. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007, 34 (12): 1313-1316.

Whyte SD, Booker PD, Buckley DG: The effects of propofol and sevoflurane on the QT interval and transmural dispersion of repolarization in children. Anesth Analg. 2005, 100 (1): 71-77.

Kuenszberg E, Loeckinger A, Kleinsasser A, Lindner KH, Puehringer F, Hoermann C: Sevoflurane progressively prolongs the QT interval in unpremedicated female adults. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2000, 17 (11): 662-664.

Pathophysiology of Heart Disease: A Collaboratice Project of Medical Students and Faculty. 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business, Baltimore, MD; Philadelphia. PA, 4

Booker PD, Whyte SD, Ladusans EJ: Long QT syndrome and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2003, 90 (3): 349-366.

Tacken MC, Bracke FA, Van Zundert AA: Torsade de pointes during sevoflurane anesthesia and fluconazole infusion in a patient with long QT syndrome. A case report. Acta Anaesthesiol Belgica. 2011, 62 (2): 105-108.

Thiruvenkatarajan V, Osborn KD, Van Wijk RM, Euler P, Sethi R, Moodie S, Biradar V: Torsade de pointes in a patient with acute prolonged QT syndrome and poorly controlled diabetes during sevoflurane anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010, 38 (3): 555-559.

Saussine M, Massad I, Raczka F, Davy JM, Frapier JM: Torsade de pointes during sevoflurane anesthesia in a child with congenital long QT syndrome. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006, 16 (1): 63-65.

Kenyon CA, Flick R, Moir C, Ackerman MJ, Pabelick CM: Anesthesia for videoscopic left cardiac sympathetic denervation in children with congenital long QT syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia–a case series. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010, 20 (5): 465-470.

Kies SJ, Pabelick CM, Hurley HA, White RD, Ackerman MJ: Anesthesia for patients with congenital long QT syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2005, 102 (1): 204-210.

De Hert SG, Van der Linden PJ, Cromheecke S, Meeus R, Nelis A, Van Reeth V, ten Broecke PW, De Blier IG, Stockman BA, Rodrigus IE: Cardioprotective properties of sevoflurane in patients undergoing coronary surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass are related to the modalities of its administration. Anesthesiology. 2004, 101 (2): 299-310.

Zhang F, Chen G, Chen C, Yan M: Sevoflurane postconditioning converts persistent ventricular fibrillation into regular rhythm. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009, 26 (9): 766-771.

Galagudza M, Kurapeev D, Minasian S, Valen G, Vaage J: Ischemic postconditioning: brief ischemia during reperfusion converts persistent ventricular fibrillation into regular rhythm. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg :Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thoracic Sur. 2004, 25 (6): 1006-1010.

Tsai SK, Lin SM, Huang CH, Hung WC, Chih CL, Huang SS: Effect of desflurane-induced preconditioning following ischemia-reperfusion on nitric oxide release in rabbits. Life Sci. 2004, 76 (6): 651-660.

Zangrillo A, Testa V, Aldrovandi V, Tuoro A, Casiraghi G, Cavenago F, Messina M, Bignami E, Landoni G: Volatile agents for cardiac protection in noncardiac surgery: a randomized controlled study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011, 25 (6): 902-907.

Piriou V, Mantz J, Goldfarb G, Kitakaze M, Chiari P, Paquin S, Cornu C, Lecharny JB, Aussage P, Vicaut E, Pons A, Lehot JJ: Sevoflurane preconditioning at 1 MAC only provides limited protection in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized bi-centre trial. Br J Anaesth. 2007, 99 (5): 624-631.

Bignami E, Landoni G, Gerli C, Testa V, Mizzi A, Fano G, Nuzzi M, Franco A, Zangrillo A: Sevoflurane vs. propofol in patients with coronary disease undergoing mitral surgery: a randomised study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012, 56 (4): 482-490.

Landoni GOF, Bignami E, Calabrò MG, D’Arpa MC, Moizo E, Mizzi AFP, Morelli A, Zangrillo A: Cardiac Protection by volatile anesthetics in non-cardiac surgery? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studeis on cilinically relevant endpoints. HSR Proc Intensive Care Cardiovasc Anesth. 2009, 1 (4):

Bassuoni AS, Amr YM: Cardioprotective effect of sevoflurane in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing vascular surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2012, 6 (2): 125-130.

Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, Calkins H, Chaikof EL, Fleischmann KE, Freeman WK, Froehlich JB, Kasper EK, Kersten JR, Riegel B, Robb JF: ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery) Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 50 (17): 1707-1732.

Tsutsumi YM, Kawaraguchi Y, Horikawa YT, Niesman IR, Kidd MW, Chin-Lee B, Head BP, Patel PM, Roth DM, Patel HH: Role of caveolin-3 and glucose transporter-4 in isoflurane-induced delayed cardiac protection. Anesthesiology. 2010, 112 (5): 1136-1145.

Hu ZY, Liu J: Effects of emulsified isoflurane on haemodynamics and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in rats with myocardial ischaemia. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009, 36 (8): 776-783.

Stumpner J, Redel A, Kellermann A, Lotz CA, Blomeyer CA, Smul TM, Kehl F, Roewer N, Lange M: Differential role of Pim-1 kinase in anesthetic-induced and ischemic preconditioning against myocardial infarction. Anesthesiology. 2009, 111 (6): 1257-1264.

Lange M, Smul TM, Blomeyer CA, Redel A, Klotz KN, Roewer N, Kehl F: Role of the beta1-adrenergic pathway in anesthetic and ischemic preconditioning against myocardial infarction in the rabbit heart in vivo. Anesthesiology. 2006, 105 (3): 503-510.

Crystal GJ, Gurevicius J, Salem MR: Isoflurane-induced coronary vasodilation is preserved in reperfused myocardium. Anesth Analg. 1996, 82 (1): 22-28.

Hohner P, Nancarrow C, Backman C, Haggmark S, Johansson G, Friden H, Diamond G, Friedman A, Reiz S: Anaesthesia for abdominal vascular surgery in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), Part I: Isoflurane produces dose-dependent coronary vasodilation. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1994, 38 (8): 780-792.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

NV-Role included reviewing manuscripts, review design, and manuscript preparation. PK-Role included review design and manuscript editing. AL-Role included literature search, review design and proof reading. RA-Role included editing and manuscript preparation. JT-Role included manuscript proof reading. JZ-Role included review design and manuscript proof reading. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Allen, N.R., Krafft, P.R., Leitzke, A.S. et al. The role of Volatile Anesthetics in Cardioprotection: a systematic review. Med Gas Res 2, 22 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-9912-2-22

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-9912-2-22