Abstract

Background

In this study, we investigated transcription and enzyme level responses of mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis exposed to hypoxic conditions. Genes for catalase (CAT), cytochrome P450, glutathione S-transferase (GST), metallothionein, superoxide dismutase (SOD), cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX-1), and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 were selected for study. Transcriptional changes were investigated in mussels exposed to hypoxia for 24 and 48 h and were compared to changes in control mussels maintained at normal oxygen levels. Activities of CAT, GST, and SOD enzymes, and lipid peroxidation (LPO) were also investigated in mussels following exposure to hypoxia for 24, 48, and 72 h.

Results

Relative to the control group, the CAT activity decreased in all hypoxia treatments, while the activity of GST significantly increased in mussels exposed to hypoxia for 24 and 48 h, but decreased in those exposed for 72 h. The LPO levels were significantly higher in mussels in the 24- and 48-h hypoxia treatments than those in the control mussels, but there was no significant change in the SOD activities among all hypoxia treatments. Messenger RNA levels for the CAT, cytochrome P450, GST, metallothionein, and SOD genes were not significantly affected by hypoxic conditions for 48 h, but the expressions of the COX-1 and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 genes were significantly repressed in mussels in both the 24- and 48-h exposure treatments.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate the transcriptional stability and changes among several genes related to oxidative stress under oxygen-depletion conditions in M. galloprovincialis and provide useful information about the modulation of antioxidant enzyme activities induced by hypoxia in a marine animal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hypoxia is defined as a dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration of <2.8 mg O2/L (equivalent to 2 mL O2/L or 91.4 mM). A number of factors result in hypoxia in aquatic environments, including natural phenomena such as vertical stratification resulting from the formation of thermoclines. However, hypoxia is often caused by excessive anthropogenic inputs of nutrients and organic matter into water bodies with poor circulation (Wu 2002).

Hypoxia and anoxia generally occur in near-bottom waters of coastal zones and estuaries, and are often associated with eutrophication, microbial respiration, and oxygen depletion (Diaz and Rosenberg 2008). In severe cases, such oxygen depletion may lead to 'dead zones’ where mass mortalities of benthic organisms occur. Nutrient runoff into aquatic environments can stimulate plant growth and lead to algal blooms (Justic et al. 1993). In such cases, the algae eventually die and are subject to oxidative decay by microorganisms, which results in the depletion of DO, which in turn can lead to hypoxia or dead zones in aquatic environments.

Hypoxic events affecting thousands of square kilometers of water have been reported worldwide, and some coastal areas (e.g., the Black Sea) have become permanently hypoxic. Indeed, hypoxia caused by eutrophication is now regarded as one of the most serious threats to coastal marine ecosystems (Goldberg 1995; McIntyre 1995). Mass mortality of invertebrates and fish, changes in ecosystem structure, altered migration and spawning patterns, reductions in habitat areas, increased susceptibility to predation, susceptibility to infections, and changes in food resources were reported to be associated with hypoxic waters worldwide (Naqvi et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2009).

Oxygen levels in aquatic environments fluctuate daily, seasonally, and spatially. Hypoxia is a major environmental stress that marine animals must tolerate in order to survive, and a variety of behavioral, physiological, and biochemical mechanisms have evolved to enable survival under oxygen-depleted conditions. Vertebrates respond to hypoxia by increasing oxygen uptake, downregulating energy expenditure, and upregulating anaerobic pathways. Fish move to colder waters in response to aquatic hypoxia (Petersen and Steffensen 2003), where the fall in body temperature reduces energy metabolism. Given that oxygen is more soluble in colder water, this migration may also be associated with an increase in the oxygen content of water. A reduction in temperature also enhances oxygen uptake because of increased hemoglobin-oxygen affinity. However, sessile invertebrates including mussels and oysters are not mobile, and their molecular responses to hypoxia at the level of gene expression and enzyme activity modulation are not well understood.

Bivalves are among the most studied marine organisms because of their ecological roles and importance. The genus Mytilus is common among marine mollusks; members of this genus occur along a wide latitudinal range in both hemispheres and play significant roles in the ecology of benthic and pelagic communities (Venier et al. 2003; Aarab et al. 2011). Members of the genus have become model study organisms because of their economic value in shellfish farming (Gueguen et al. 2011) and their role as bioindicators (Moreira and Guilhermino 2005; Kayhan et al. 2007). Molecular studies showed that changes in gene expressions can explain specific cell responses in mollusks, as exemplified by the enhanced expression of metallothioneins following exposure of mussels to toxic metals (Geffard et al. 2005; Fasulo et al. 2008).

In a recent study, we reported differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and transcriptional changes in several DEGs in marine mussels in response to oxygen-depletion stress (Woo et al. 2011). In the present study, we investigated transcriptional changes of seven genes related to oxidative stress and representative antioxidant enzyme activities in a marine mussel exposed to hypoxia.

Methods

The mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis (6.0 to 6.5 cm) was collected in Jangmok Bay, Geoje, Republic of Korea (Figure 1) and acclimated in an aquaculture facility for a week in filtered seawater at 22°C with a salinity of 35 psu and a light/dark cycle of 14:10 h. The experimental groups were exposed to hypoxic stress (DO of 2 mg/L) for 24, 48, and 72 h, while the control groups were kept in natural seawater. The DO levels were controlled by a nitrogen flow unit (AquaController Pro Base Unit, Neptune, Shelton, CT, USA) as described Woo et al. (2011), and the DO level in each tank of water was maintained at a constant level until the end of the experiment.

Catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities, and lipid peroxidation (LPO) levels were investigated in 24-, 48-, and 72-h exposure groups and were compared to the control group. Muscle was chosen as the target organ since it occupies most of the body and is involved in energy-consuming movements by bivalve mollusks. The tissue was homogenized using a tissue homogenator (Bioneer Corporation, Daejeon, Republic of Korea) in four volumes of 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.6), containing 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 M sucrose, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.15 M KCl, and 0.1 M PMSF. The homogenate was centrifuged at 9,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was stored at -80°C. The quantities of proteins were determined according to the Bradford (1979) method using the Coomassie blue reagent. The CAT activity was assayed by the method of Claiborne (1985). The reaction mixture consisted of 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 0.019 M hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and 10% phenazonium methosulfate (PMS) in a final volume of 3 mL. The change in absorbance was recorded at 240 nm. The CAT activity was calculated in terms of nanomoles of H2O2 consumed per minute per milligram of protein. The GST activity was determined by the Habig method with some modifications (Habig et al. 1974). The reaction mixture consisted of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 1 mM glutathione (GSH, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 1 mM 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB, Sigma) and 10% PMS in a total volume of 2 mL. The change in absorbance at 25°C was recorded at 340 nm, and the enzyme activity was calculated as nanomoles of the CDNB conjugate formed per minute per milligram of protein using a molar extinction coefficient of 9.6 × 103/M · cm. The SOD activity was determined according to the method described by Kono (1978) with some modifications. The reaction mixture consisted of 0.725 mL Tris-buffer (50 mM, pH 8.3, Sigma), 0.1 mL nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT, 500 mM, Sigma), 0.1 mL of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH, 780 mM, Sigma), and different volumes (0.025, 0.050, 0.075, 0.1, and 0.050 mL) of PMS (Sigma). The change in absorbance was recorded at 560 nm. The activity was reported by its ability to inhibit 50% of the reduction of NBT, and the result is expressed as units per minute per milligram protein. LPO was determined according to the method described by Fatima et al. (2000) with some modifications. The tissue was homogenized in a chilled 0.1 M potassium chloride solution. The assay mixture contained 0.67% thiobarbituric acid (TBA, Sigma), 10% chilled trichloroacetic acid, and homogenate (10%) in a total volume of 3 mL. The LPO rate was expressed as nanomoles of TBA-reactive substances formed of tissue using a molar extinction coefficient of 1.56 × 105/M · cm.

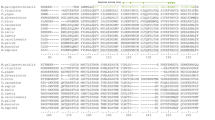

The tissues from the mussels were dissected after exposure to hypoxia, and the total RNA was extracted as described by Woo et al. (2011). The changes in the expressions of oxidative stress-related genes (CAT, cytochrome P450, GST, metallothionein, SOD, cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COX-1), and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2) in each independent hypoxia-exposure experiment were quantified using a real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis as described by Woo et al. (2011). The primer sequences for each target gene are shown in Table 1. For the qRT-PCR analysis, the data were obtained from triplicate experiments. Group means were compared using a one-way analysis of variance followed by Duncan's test for multiple comparisons. A value of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

To determine the appropriate duration of exposure of mussels to hypoxia for the experiment, we performed a mortality test. Twelve mussels were exposed to 2 mg/L of DO for 10 days in a water tank, while a control group of mussels was maintained in natural seawater. No mortality was observed at 4 days of exposure in either the hypoxia treatment or the control. Approximately 60% of the mussels in the 2 mg/L DO treatment had died after 7 days, and a further 33% had died after 10 days (Figure 2).

Mortality by exposure period in Mytilus galloprovincialis exposed to hypoxia. The number of survivors is indicated on the Y-axis, and the exposure duration (days) is on the X-axis. Mortality was determined in triplicate experiments and is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 12). Square, control group (8 mg/L dissolved oxygen (DO 8)); circle, DO 2 exposure group.

To determine the enzyme activities occurring under hypoxic conditions, sets of six mussels were exposed to 2 mg/L of DO for 24, 48, and 72 h. In each treatment, the CAT activity significantly decreased compared to that in the control group and was reduced to approximately 33% in mussels after 72 h of treatment (Figure 3a). Relative to the control mussels, the GST activity had increased by a factor of 2 in mussels after 24 h of treatment and by a factor of 2.7 after 48 h of treatment, but had declined by 60% after 72 h of treatment (Figure 3b). Following 72 h of hypoxia, no significant change in SOD activity was detected in any hypoxia treatment group, but the LPO levels increased in all mussels exposed to hypoxia (Figure 3c,d), with levels twofold higher following 24 and 48 h of exposure relative to the control group (p < 0.05).

Changes in enzyme activities in mussels exposed to hypoxia. Mussels were exposed to 2 mg/L dissolved oxygen (DO 2) for 24, 48, and 72 h. CAT, GST, and SOD activities, and LPO levels were measured. The relative enzyme activity is indicated on the Y-axis, and the exposure duration (h) is on the X-axis. (a) CAT activity changes in mussels exposed to hypoxia; (b) GST activity changes in mussels exposed to hypoxia; (c) SOD activity changes in mussels exposed to hypoxia; (d) LPO level changes in mussels exposed to hypoxia. Asterisk denotes significant difference from the control group (p < 0.05).

No significant changes in expressions of genes related to oxidative stress investigated in this study were detected following exposure to hypoxia, with the exception of the COX-1 and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (nad2) genes (Figure 4). The transcription of CAT (cat), cytochrome P450 (cyp4y1), metallothionein (mt), and SOD (sod) showed similar expression patterns, with expressions slightly decreasing (by factors of 1.1 to 1.4) at 24 h of exposure, then recovering to the level of the control group. The transcription of GST (gst) was slightly upregulated (by a factor of 1.4) at 24 h, but thereafter decreased to a level similar to that of the control group. While the transcriptions of the cat, cyp4y1, mt, sod, and gst genes did not significantly change, the expressions of cox1 and nad2 were strongly downregulated in the mussels exposed to hypoxia for 24 and 48 h. The transcription of cox1 decreased by approximately an order of magnitude in mussels exposed to hypoxia for 24 h and by a factor of 2 in those exposed for 48 h, compared to the control group (p < 0.05). The transcription of nad2 was downregulated by approximately an order of magnitude in mussels exposed to hypoxia for 24 and 48 h (p < 0.05).

Changes in expressions of oxidative stress-related genes in Mytilus galloprovincialis with hypoxia exposure. Mussels were exposed to 2 mg/L dissolved oxygen (DO 2) for 24 and 48 h, and RNAs were extracted from muscle tissues. mRNA levels were evaluated by a real-time quantitative PCR, and results are expressed relative to actin expression levels. Each histogram represents the mean ± SD (n = 3). Asterisk indicates significant difference from each control group (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Hypoxia can result from several natural factors, including stratification of the water column but is often a consequence of pollution and eutrophication involving phytoplankton blooms. Photosynthesis by phytoplankton blooms increases DO saturation during the day, but their respiration during the night reduces DO saturation. Bays consisting of shallow semi-enclosed water bodies are particularly prone to reduced vertical mixing between water layers, thereby restricting the supply of oxygen from surface waters to more-saline bottom waters (Figure 1). When oxygen depletion progresses to hypoxia, fish kills may occur, and benthic invertebrates, including clams, may also perish.

The purpose of this study was to assess the biological responses of a sessile marine invertebrate to acute hypoxia and was particularly aimed at assessing responses at the molecular level. The genes involved in stress-defense mechanisms can be used as effective biomarkers of physiological changes in organisms that result from both endogenous and exogenous stressors. The levels of expressions of such genes can serve as a critical 'early warning system’ for assessing environmental and organismal health. In this study, the transcription levels of cat, cyp4y1, mt, sod, gst, cox1, and nad2 in M. galloprovincialis and the activities of representative enzymes related to oxidative stress were quantitatively compared between mussels exposed to hypoxia and control mussels under normoxic conditions.

The relative contribution of each antioxidant enzyme to protection against hypoxia-associated oxidative stress during periods of oxygen depletion is not well known, and the relationships among reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, GSH levels, oxidative stress markers, and activities of antioxidant enzymes are complex. Our results showed that the activity of the SOD antioxidant enzyme remained unchanged, but the activities of CAT and GST significantly changed upon exposure to hypoxia. While the CAT activity decreased during hypoxia, the GST activity increased within 48 h of exposure, and their gene expressions showed similar patterns of change within 48 h. CAT is the major enzyme and primary antioxidant defense involved in H2O2 detoxification (catalyzing the conversion of H2O2 to water and oxygen), while GST catalyzes a variety of reactions that detoxify endogenous compounds, including peroxidized lipids (Das and Bishayi 2010; Turkanoglu et al. 2010). We found that both CAT activity and cat expression decreased with oxygen depletion. Although the transcriptional change in cat was not statistically significant, the trends of CAT activity and cat expression were identical. Interpreting the discrepancy between CAT activity and cat messenger RNA (mRNA) levels may be possible by measuring the changes in protein levels using an antibody specific for the CAT protein. The animals with depleted CAT activity could be subject to severe hypoxia followed by reoxygenation (Welker et al. 2012). Hypoxia did not induce changes in the SOD activity or sod transcription in our study, but increased activities of GST and LPO were detected in mussels exposed to hypoxia. This suggests that the hypoxia-induced reduction in CAT activity caused a redox imbalance, which was sufficient to induce further oxidative stress that led to increased activities of GST and LPO in mussels.

Oxygen is the ultimate electron acceptor for mitochondrial respiration in a process catalyzed by COX. In mammals, the oxygen concentration regulates gene transcription of COX subunits (Roemgens et al. 2011). Oxygen is also required for aerobic energy metabolism processes including oxidative phosphorylation. Low-oxygen conditions activate the hypoxia signaling pathway in eukaryotic cells, primarily through the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor (HIF) (Fu et al. 2008). We did not investigate the changes in the HIF gene expression, but the low oxygen concentration affected cox1 and nad2 transcription, and both genes were significantly downregulated in mussels exposed to hypoxia. Similar results were reported in a gene-expression study involving the grass shrimp Palaemonetes pugio exposed to hypoxia, where the transcription of cox1 was downregulated at 12-h post exposure (Li and Brouwer 2009). In addition, the levels of cox1 transcription and COX activity decreased in the insects Epiblema scudderiana and Eurosta solidaginis in response to hypoxia (McMullen and Storey 2008). It therefore appears that the decrease in cox1 transcription results in decreased mitochondrial COX protein synthesis, suggesting that mitochondrial genes and proteins are promising molecular indicators of exposure to hypoxia.

The NADH dehydrogenase 1α subcomplex is a respiratory chain enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of two electrons from NADH to ubiquinone in a reaction associated with proton translocation across the membrane and one of the HIF-1 target genes (Tello et al. 2011). It was reported that high levels of ROS and high metabolic activity are involved in inducing the expression of the NADH dehydrogenase 1α subcomplex gene (Masuo et al. 2010; Bruckbauer and Zemel 2011). We found that a low oxygen concentration reduced nad2 transcription in mussels, and the expression of the gene was downregulated by approximately an order of magnitude relative to the control group. NADH dehydrogenase is the first and largest enzyme complex in the mitochondrial oxygen respiration chain. It is noteworthy that the NADH dehydrogenase complex is considered important in the adaptive evolution of the mammalian mitochondrial genome (da Fonseca et al. 2008). In animals living at high elevations and in low-oxygen environments, the NADH dehydrogenase complex was found to be under positive selection in residue substitutions (Yu et al. 2011). This was thought to interfere with metabolic performance (Hassanin et al. 2009). In this study, we only investigated nad2 gene expression in mussels responding to hypoxia. In addition to investigating the transcriptional regulation of the NADH dehydrogenase complex, characterizing the substitutions in the NADH dehydrogenase complex and adaptations to oxygen respiration in mussels appears to be an important area for further study concerning animal responses to hypoxia associated with ocean warming. Unlike fish, which can move to colder waters in response to hypoxia and thus decrease their body temperature to reduce energy metabolism, sessile invertebrates including mussels cannot move in response to hypoxia and must use alternative strategies such as downregulation of energy expenditure or reoxygenation.

The greatest difficulty in assessing environmental stresses like oxygen depletion is that visible responses to external stimuli can be determined when organisms are exposed to high stress levels. In addition, assessing physiological, behavioral, or ecological changes induced by environmental stresses tends to require long-term observations. However, the approach using changes in gene expressions allows the detection of biological responses at low stress levels and downstream biological interpretation. The genes investigated in this study are known to play roles in detoxification and are crucial factors in determining the sensitivity of cells to various toxic chemicals, including environmental pollutants and products of oxidative stress. The data suggest that changes in gene expression do not always correspond with enzyme activities. This can be explained by biological responses like gene expression changes appearing in the initial stage after exposure to environmental stresses and their triggering subsequent signals like protein expression or activity changes depending on the intensity of the stimuli. Although changes in protein amounts or enzyme activities were not found after the environmental stimuli, external stresses definitely affect intracellular processes of organisms involved in survival and adaptation, and the effects appear as downstream responses.

Conclusions

The results demonstrate that acute hypoxia affects the activities of antioxidant enzymes and expressions of genes related to oxidative stress, and thus suggest that changes in transcription levels of oxidative-stress genes are a potential indicator of oxygen depletion conditions in M. galloprovincialis. In this study, we carried out lab-scale experiments using mussels, and further studies using experimental mesocosms (Molina et al. 2012) could help interpret detailed responses to environmental stresses and interactions with other organisms.

References

Aarab N, Godal BF, Bechmann RK: Seasonal variation of histopathological and histochemical markers of PAH exposure in blue mussel ( Mytilus edulis L.). Mar Environ Res 2011, 71: 213–217. 10.1016/j.marenvres.2011.01.005

Bradford M: A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram of protein utilizing the principal of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1979, 72: 248–254.

Bruckbauer A, Zemel MB: Effects of dairy consumption on SIRT1 and mitochondrial biogenesis in adipocytes and muscle cells. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011, 8: 91. 10.1186/1743-7075-8-91

Claiborne A: Catalase activity. In CRC handbook of methods for oxygen radical research. Edited by: Greenwald RA. CRC, Boca Raton, FL; 1985.

da Fonseca RR, Johnson WE, O'Brien SJ, Ramos MJ, Antunes A: The adaptive evolution of the mammalian mitochondrial genome. BMC Genom. 2008, 9: 119. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-119

Das D, Bishayi B: Contribution of catalase and superoxide dismutase to the intracellular survival of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in murine macrophages. Indian J Microbiol 2010, 50: 375–384. 10.1007/s12088-011-0063-z

Diaz RJ, Rosenberg R: Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science 2008, 321: 926–929. 10.1126/science.1156401

Fasulo S, Mauceri A, Giannetto A, Maisano M, Bianchi N, Parrino V: Expression of metallothionein mRNAs by in situ hybridization in the gills of Mytilus galloprovincialis , from natural polluted environments. Aquat Toxicol 2008, 88: 62–68. 10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.03.009

Fatima M, Ahmad I, Sayeed I, Athar M, Raisuddin S: Pollutant-induced over-activation of phagocytes is concomitantly associated with peroxidative damage in fish tissues. Aquat Toxicol 2000, 49: 243–250. 10.1016/S0166-445X(99)00086-7

Fu D, Dai A, Hu R, Chen Y, Zhu L: Expression and role of factor inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in pulmonary arteries of rat with hypoxia-induced hypertension. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2008, 40: 883–892.

Geffard A, Amiard-Triquet C, Amiard JC: Do seasonal changes affect metallothionein induction by metals in mussels, Mytilus edulis ? Ecotoxicol Environ Safety 2005, 61: 209–220. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.01.004

Goldberg ED: Emerging problems in the coastal zone for the twenty-first century. Mar Pollut Bull 1995, 31: 152–158. 10.1016/0025-326X(95)00102-S

Gueguen M, Amiard JC, Arnich N, Badot PM, Claisse D, Guerin T, Vernoux JP: Shellfish and residual chemical contaminants: hazards, monitoring, and health risk assessment along French coasts. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2011, 213: 55–111. 10.1007/978-1-4419-9860-6_3

Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Jakoby WB: Glutathione S-transferases. The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J Biol Chem 1974, 249: 7130–7139.

Hassanin HA, Hannibal L, Jacobsen DW, El-Shahat MF, Hamza MS, Brasch NE: Mechanistic studies on the reaction between R2N-NONOates and aquacobalamin: evidence for direct transfer of a nitroxyl group from R2N-NONOates to cobalt(III) centers. Anqew Chem Int Ed Engl 2009, 48: 8909–8913. 10.1002/anie.200904360

Justic D, Rabalais NN, Turner RE, Wiseman WJ Jr: Seasonal coupling between riverborne nutrients, net productivity and hypoxia. Mar Pollut Bull 1993, 26: 184–189. 10.1016/0025-326X(93)90620-Y

Kayhan FE, Gulsoy N, Balkis N, Yuce R: Cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) levels of Mediterranean mussel ( Mytilus galloprovincialis Lamarck, 1819) from Bosphorus, Istanbul. Turkey. Pak J Biol Sci 2007, 10: 915–919. 10.3923/pjbs.2007.915.919

Kono Y: Generation of superoxide radical during autoxidation of hydroxylamine and an assay for superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys 1978, 186: 189–195. 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90479-4

Li T, Brouwer M: Gene expression profile of grass shrimp Palaemonetes pugio exposed to chronic hypoxia. Compar Biochem Physiol Part D Genom Proteom 2009, 4: 196–208. 10.1016/j.cbd.2009.03.004

Masuo S, Terabayashi Y, Shimizu M, Fujii T, Kitazume T, Takaya N: Global gene expression analysis of Aspergillus nidulans reveals metabolic shift and transcription suppression under hypoxia. Mol Genet Genom 2010, 284: 415–424. 10.1007/s00438-010-0576-x

McIntyre AD: Human impact on the oceans: the 1990s and beyond. Mar Pollut Bull 1995, 31: 147–151. 10.1016/0025-326X(95)00099-9

McMullen DC, Storey KB: Mitochondria of cold hardy insects: responses to cold and hypoxia assessed at enzymatic, mRNA and DNA levels. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2008, 38: 367–373. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.12.003

Molina FR, de Paggi SJ, Frau D: Impacts of the invading golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei on zooplankton: a mesocosm experiment. Zool Stud 2012, 51: 733–744.

Moreira SM, Guilhermino L: The use of Mytilus galloprovincialis acetylcholinesterase and glutathione S-transferase activities as biomarkers of environmental contamination along the northwest Portuguese coast. Environ Monitor Assess 2005, 105: 309–325. 10.1007/s10661-005-3854-z

Naqvi SWA, Jayakumar DA, Narvekar PV, Naik H, Sarma VVSS, D'Souza W, et al.: Increased marine production of N2O due to intensifying anoxia on the Indian continental shelf. Nature 2000, 408: 346–349. 10.1038/35042551

Petersen MF, Steffensen JF: Preferred temperature of juvenile Atlantic cod Gadus morhua with different haemoglobin genotypes at normoxia and moderate hypoxia. J Exp Biol 2003, 206: 359–364. 10.1242/jeb.00111

Roemgens A, Singh S, Beyer C, Arnold S: Inducers of chemical hypoxia act in a gender- and brain region-specific manner on primary astrocyte viability and cytochrome C oxidase. Neurotox Res 2011, 20: 1–14. 10.1007/s12640-010-9213-z

Tello D, Balsa E, Acosta-Iborra B, Fuertes-Yebra E, Elorza A, Ordoñez A, Corral-Escariz M, Soro I, López-Bernardo E, Perales-Clemente E, Martínez-Ruiz A, Enríquez JA, Aragonés J, Cadenas S, Landázuri MO: Induction of the mitochondrial NDUFA4L2 protein by HIF-1alpha decreases oxygen consumption by inhibiting complex I activity. Cell Metab 2011, 14: 768–779. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.008

Turkanoglu A, Can Demirdogen B, Demirkaya S, Bek S, Adali O: Association analysis of GSTT1, GSTM1 genotype polymorphisms and serum total GST activity with ischemic stroke risk. Neurol Sci 2010, 31: 727–734. 10.1007/s10072-010-0330-5

Venier P, Pallavicini A, De Nardi B, Lanfranchi G: Towards a catalogue of genes transcribed in multiple tissues of Mytilus galloprovincialis . Gene 2003, 314: 29–40.

Welker A, Campos E, Cardoso L, Hermes-Lima M: Role of catalase on the hypoxia/reoxygenation stress in the hypoxia-tolerant Nile tilapia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Compar Physiol 2012, 302: 1111–1118. 10.1152/ajpregu.00243.2011

Woo S, Jeon HY, Kim SR, Yum S: Differentially displayed genes with oxygen depletion stress and transcriptional responses in the marine mussel, Mytilus galloprovincialis . Compar Biochem Physiol Part D Genom Proteom 2011, 6: 348–356. 10.1016/j.cbd.2011.07.003

Wu RSS: Hypoxia: from molecular responses to ecosystem responses. Mar Pollut Bull 2002, 45: 35–45. 10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00061-9

Yu L, Wang X, Ting N, Zhang Y: Mitogenomic analysis of Chinese snub-nosed monkeys: evidence of positive selection in NADH dehydrogenase genes in high-altitude adaptation. Mitochondrion 2011, 11: 497–503. 10.1016/j.mito.2011.01.004

Zhang Z, Ju Z, Wells MC, Walter RB: Genomic approaches in the identification of hypoxia biomarkers in model fish species. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 2009, 381: S180-S187.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by KIOST project nos. PE98928 and PMS258B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SW and SY prepared the entire manuscript. VD, GL, TL, and KS carried out the molecular analyses, and HW carried out the general molecular works. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Woo, S., Denis, V., Won, H. et al. Expressions of oxidative stress-related genes and antioxidant enzyme activities in Mytilus galloprovincialis (Bivalvia, Mollusca) exposed to hypoxia. Zool. Stud. 52, 15 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1810-522X-52-15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1810-522X-52-15