Abstract

Transposable elements (TEs) comprise a large fraction of mammalian genomes. A number of these elements are actively jumping in our genomes today. As a consequence, these insertions provide a source of genetic variation and, in rare cases, these events cause mutations that lead to disease. Yet, the extent to which these elements impact their host genomes is not completely understood. This review will summarize our current understanding of the mechanisms underlying transposon regulation and the contribution of TE insertions to genetic diversity in the germline and in somatic cells. Finally, traditional methods and emerging technologies for identifying transposon insertions will be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the 60 years since Barbara McClintock first discovered transposable elements (TEs), it has become increasingly recognized that these mobile sequences are important components of mammalian genomes and not merely 'junk DNA'. We now appreciate that these elements modify gene structure and alter gene expression. Through their mobilization, transposons reshuffle sequences, promote ectopic rearrangements and create novel genes. In rare cases, TE insertions which cause mutations and lead to diseases both in humans and in mice have also been documented. However, we are at the very earliest stages of understanding how mobile element insertions influence specific phenotypes and to the extent to which they contribute to genetic diversity and human disease.

TEs are categorized into two major classes based on their distinct mechanisms of transposition. DNA transposons, referred to as Class II elements, mobilize by a 'cut-and-paste' mechanism in which the transposon is excised from a donor site before inserting into a new genomic location. These elements are relatively inactive in mammals, although one notable exception is a piggyBac element recently identified to be active in bats ([1], R Mitra and N Craig, personal communication). In humans, DNA transposons represent a small fraction (3%) of the genome [2]. Retrotransposons, also known as Class I elements, mobilize by a 'copy-and-paste' mechanism of transposition in which RNA intermediates are reverse transcribed and inserted into new genomic locations. These include long terminal repeat (LTR) elements such as endogenous retroviruses, and non-LTR retrotransposons. Endogenous retroviruses are remnants of viruses that have lost the ability to re-infect cells. These elements, which comprise 8% of the human genome, perform reverse transcription in cytoplasmic virus-like particles [2]. In contrast, non-LTR retrotransposons undergo a distinct mechanism of transposition whereby their RNA copies undergo reverse transcription and integration through a coupled process that occurs on target genomic DNA in the nucleus [3–5].

Of all mobile element families, only the retrotransposons remain actively mobile in the human and primate genomes and serve as ongoing sources of genetic variation by generating new transposon insertions. LINEs (long interspersed nucleotide elements) represent the most abundant autonomous retrotransposons in humans, accounting for approximately 18% of human DNA. Non-autonomous elements such as SINEs (short interspersed nucleotide elements) and SVAs [hybrid SINE-R-VNTR (variable number of tandem repeat)-Alu elements] require LINE-1 (L1) encoded proteins for their mobilization [2, 6–9]. Together, SINEs and SVA elements occupy ~13% of the human genome.

It is both impressive and puzzling that almost half of our genome is composed of these repeat sequences. Evolutionary paradigms dictate that useless elements and harmful TE insertions events should be selected against, while beneficial insertions should gain a selective advantage and thus be retained. Indeed, the most successful transposons have co-evolved with their hosts. Most transposable element insertions are expected to have few consequences for the host genome and, therefore, have little to no impact on gene function [10]. Rarely, transposon insertions will have a deleterious effect on their host genome, resulting in human disease. To date, approximately 65 disease-causing TE insertions (due to L1, SVA and Alus) have been documented in humans [11]. Less frequently recognized are instances in which transposons have made innovative contributions to the human genome. In these cases, mobile element sequences have been co-opted by the host genome for a new purpose. For example, approximately 150 human genes have been derived from mobile genetic sequences [2, 12, 13]. Perhaps the best studied example of a domesticated transposon is the RAG1 endonuclease, which initiates V(D)J recombination leading to the combinatorial generation of antigen receptor genes. The RAG endonucleases have been demonstrated to function as transposases in vitro, providing strong support for the idea that the V(D)J recombination machinery evolved from transposable elements [14–16].

In this review, we examine mechanisms of transposon regulation and discuss how TE insertions account for genetic diversity in the germline and in somatic cells. Traditional methods and recently developed technologies for identifying these insertions will also be considered.

Mechanisms of TE regulation

Expansion of mobile elements occurs when de novo insertions are transmitted through the germline to subsequent generations. Indeed, successful metazoan transposons often show germline-restricted expression. As TEs pose a significant threat to genome integrity, uncontrolled activation of these elements would imperil both the host and the element. It appears that, as a consequence, metazoan genomes have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to limit the mobilization of these elements.

DNA methylation is, perhaps, the most well understood mechanism involved in the regulation of TEs in the germline of plants, fungi and mammals [17–20]. Cytosine methylation silences LTR and non-LTR elements by blocking transcription of retrotransposon RNA. Host suppression mechanisms appear to function post-transcriptionally as well. For example, the premature termination of transcription and alternative splicing inhibits expression of LINE-1 elements [21, 22]. A family of RNA/DNA editing enzymes with cytosine deaminase activity known as APOBECs (apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide) has been found to inhibit LINE-1, Alu, and mouse IAP (intracisternal A particle) elements [23]. Interestingly, suppression of retrotransposons by APOBECs does not require any editing activity, suggesting that these proteins may carry out a novel function in addition to their ability to act as cytosine deaminases. Several groups have proposed that APOBECs may sequester retrotransposon RNA in cytoplasmic complexes, although additional studies are warranted in order to prove this hypothesis [24, 25]. RNA interference is believed to control retrotransposition [26], although the observed effect in mammalian cells in vitro is modest [27, 28].

Recently, a novel form of mobile element control has emerged that involves small RNAs in germ cells [29]. At the heart of this pathway is a class of small RNAs [piwi-interacting RNA (piRNAs)] that bind to the germline-restricted Piwi subclass of the Argonaute family of RNA interference effector proteins. In Drosophila, piRNAs are enriched in sequences containing retrotransposons and other repetitive elements. Disruption of Piwi proteins results in the reduction in piRNA abundance and transposon derepression [30, 31]. A series of elegant studies in Drosophila and zebrafish directly implicated Piwi proteins in piRNA biogenesis to maintain transposon silencing in the germline genome [32–34]. These findings have led to the idea that piRNAs might immunize the Drosophila germline against potentially sterilizing transposition events [32, 35].

Mutations in two mouse Piwi orthologues (Mili and Miwi2) result in the loss of TE methylation in the testes, transposon derepression and meiotic arrest during spermatogenesis [36, 37]. Interestingly, the mouse MAELSTROM (MAEL) protein was found to interact with MILI and MIWI in the germline-specific structure nuage[38], suggesting that MAEL may also function in this pathway. Nuage (French for 'cloud') is a perinuclear electron-dense structure found in the germ cells of many species [39]. In flies, Mael is required for the accumulation of repeat-associated small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and repression of TEs [40]. Soper et al. demonstrated that loss of Mael leads to germ cell degeneration (at the same point in meiosis as Mili and Miwi2 mutants) and male sterility in mice [41]. In addition, they provided evidence that the mammalian MAEL protein is essential for the silencing of retrotransposons and determined that early meiosis is a critical timepoint when transposon control is established in the male germline. More recently, a similar role for another germ cell protein, GASZ, has been uncovered [42]. Given that MAEL, MILI, MIWI and GASZ all localize to nuage (chromatoid body in mammals), this structure is likely where the piRNA pathway defends the germline genome from the invasion of unchecked transposable elements.

Consequences of TE insertions in the germline

New retrotransposon insertions arising in or passing through the germline can lead to constitutional genetic diseases in humans, although these are uncommonly recognized events. Not surprisingly, it is the TE families most actively propagating themselves in the human genome that are found to cause these diseases, namely and in order of prevalence, Alu s, L1 s and SVAs.

As a result of male hemizogosity for the X chromosome, loss-of-function mutations affecting boys have been disproportionately described. Examples include numerous Alu and L1-induced coagulopathies by disruption of coagulation factor VIII or factor IX [43, 44], Alu and SVA insertions causing immunodeficiency by disrupting BTK [45] and LINE-1 insertions in the large dystrophin locus resulting in muscular dystrophies and cardiomyopathies [46–48].

Autosomal transposon insertions leading to human disease have also been described. These tend to phenocopy otherwise autosomal dominant diseases caused by mutation of the transposon target locus. Examples include an intronic Alu insertion disrupting function of the NF1 tumour suppressor and causing clinical neurofibromatosis [49] and a small number of independent Alu insertions affecting fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) and causing malformations with craniosynostosis categorized as Apert syndrome [50, 51].

Thus, while most de novo insertions are likely to be passed on as phenotypically silent repeats, it is well established that transposon insertions are relevant to human clinical genetics and can have severe phenotypic consequences in rare cases [52, 53]. There remains significant speculation about whether our understanding of this is limited by the technical difficulties in detecting these sequences (discussed below) or if retrotransposition is indeed effectively prevented so that de novo insertions uncommonly underlie human disease.

Transposon insertions in somatic cells

There is a widely accepted belief that truly 'selfish' genetic elements must mobilize selectively in the germline or during early development in order to guarantee their evolutionary success. However, recent evidence from several laboratories challenges this notion. Belancio and colleagues reported that both full-length and processed L1 transcripts are detected in human somatic tissues as well as in transformed cells [54]. Kubo and colleagues demonstrated that L1 retrotransposition occurs in a low percentage of primary fibroblasts and hepatocyes when an adenoviral delivery system is employed to express the L1 element [55]. Additionally, L1 somatic retrotransposition events have been discovered in blastocysts from transgenic mouse and rat models expressing a human L1 element [56]. These data suggest that L1 elements contribute to somatic mosaicism. The proposed model is that L1 RNA transcribed in germ cells is carried over through fertilization and then integrates during embryogenesis. At least one case of human disease appears traceable to a similarly timed insertion in a mosaic mother who transmitted the insertion to her child [57]. Somatic insertions have also been identified in mouse models expressing a synthetic mouse L1 element [58]. However, in these studies the elements are expressed from heterologous promoters.

Gage and colleagues reported that L1 retrotransposition occurs in cultured mouse neuronal progenitor cells and in a mouse model harboring a human L1 element [59]. Based on these findings, it is hypothesized that L1 retrotransposition events might contribute to neuronal plasticity and, perhaps, individuality. In a recent follow-up study, Gage and colleagues detected an increase in the copy number of endogenous L1 in several regions of the adult human brain compared to the copy number of these elements in liver or heart genomic DNA from the same person [60]. In some cases, the brain samples contained ~80 additional copies of L1 sequence per cell. The functional consequences of these findings are, as yet, unknown and many questions remain regarding whether these brain-specific L1 insertions could potentially affect neuronal cell function. Despite these unanswered questions, interesting parallels can be drawn between neuronal cell diversity and the immune system. Namely, immune cells are the only other somatic cell type known to undergo an orchestrated genomic sequence-level alteration process whereby genes that encode antibodies are shuffled to create a host of antibodies that recognize a large number of antigens. Given that the human nervous system embodies a seemingly equally astounding degree of complexity and variability, it is possible that L1 mobilization may play a role in somatic cell diversity. Yet, dysregulation of transposon control mechanisms in the brain might also contribute to neurologic disease.

The extent to which TE insertions may generate diversity in somatic cells remains largely unexplored. It remains unclear why transposons do not hop more often in somatic cells. One possibility is that a transposon defense pathway present in somatic cells has yet to be discovered. One potential candidate involved in somatic TE repression might be the P body (processing body), the somatic equivalent of the germline-specific structure nuage. These cytoplasmic structures contain enzymes involved in RNA turnover, including members of the RNA-induced silencing complex. L1 RNA and ORF1 have been shown to accumulate in stress granules, which associate with P bodies in somatic cells [61]. It is tempting to speculate that these structures somehow coordinate repression of TEs in somatic cells, although additional studies are necessary.

Mobile elements and cancer

A hallmark of neoplastic proliferation is the accumulation of somatic genetic changes. Many types of cancer involve recurrent karyotypic abnormalities or other forms of genomic instability. The roles that mobile elements may play in these processes have been largely speculative. In humans, constitutionally integrated transposons have fairly well established roles as substrates in non-allelic homologous recombinations; but do they also potentiate oncogenesis by somatic expression of, for example, genotoxic L1-encoded proteins? Beyond this, are they capable of completing retrotransposition in such a way as to inactivate key tumor suppressor genes? In rare cases, they do appear to do the latter. For example, LINE-1 retransposition was shown to be an important step in the development of a colon cancer when a tumor-specific exonic insertion in adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC) was described [62]. Using an approach that combines linker-mediated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and high-throughput sequencing (to be discussed in the next section), Iskow and colleagues recently identified several L1 insertions in human lung tumor samples [63]. Although mutations with functional consequences were not demonstrated, these data support a model whereby L1 activity creates tumor genomic heterogeneity. This underscores at least possible roles for transposon insertions in tumor progression.

Suggesting that transposons may have tumor-specific effects dependent on their expression is the observation that demethylation of their promoter sequences have been described in several human tumors. Several examples for the L1 promoter are described in Table 1. In most cases, studies have not convincingly carried these observations further to document that this results in full-length LINE-1 transcripts or expression of functional ORF1p and ORF2p proteins. In a few documented cases, full length L1 RNA in cancer cell lines [54, 64] and expression of ORF1p in pediatric germ cell tumors [65] and breast cancer [66] have been shown. Thus, it is possible that tumors provide an environment where transposition events can occur and be selected for in transformation. In at least one animal model, the mouse Dnmt1 hypomorph, activation of endogenous retroelements is involved in lymphomagenesis. Presumably, hypomethylation caused by compromise of the DNA methyltransferase leads to unchecked activity of endogenous IAPs which then integrate in the Notch1 locus to generate an oncogenic gain-of-function allele [67]. This occurred independently but recurrently in seven of the 16 lymphomas studied.

While the genotoxic potential of L1 encoded ORF2p has been recognized, a recent paper by Lin et al. [68] raised an interesting model suggesting that the protein contributes to tumor development by inducing double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) breaks at specifically targeted sites to which it is recruited. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation in prostate adenocarcinoma cells, the authors demonstrated an androgen ligand-dependent localization of ORF2p to a prostate cancer chromosomal translocation interval. Rather than promoting retrotransposition, their model suggests the endonuclease activity leaves DNA breaks thus subjecting the region to erroneous repair by non-homologous end joining pathways ultimately responsible for the translocation. What factors are responsible for the recruitment and whether ORF2p functions similarly at other breakpoint hot spots in other neoplasias remains unknown.

In addition to the potential role of endogenous TEs in cancer, it should be noted that several laboratories have utilized transposons as tools for cancer gene identification in forward genetic insertional mutagenesis screens in mice. For example, the Sleeping Beauty (SB) DNA transposon system has been successfully used to identify novel cancer genes in tissues that could not be previously analysed by slow transforming retroviruses [69, 70]. Recently, this approach has been modified through the conditional activation of the SB in specific tissues [71, 72]. With the recent development of a codon-optimized L1 element, it appears that retrotransposons may also serve as useful mutagenesis tools [58, 73]. As these elements mobilize by a copy and paste mechanism of retrotransposition, their donor elements are stable. L1 mouse models may also be controlled by tissue-specific promoters and be engineered to contain gene traps [74]. One potential advantage of an unbiased TE-based approach is the ability to study how specific mutations affect tumor cell initiation, progression and maintenance in well-defined, genetically engineered mouse models. Thus, it is likely that these models will provide a complementary approach to cancer genome sequencing studies by uncovering functionally relevant mutations that can further be studied as potential therapeutic targets.

Strategies for identifying TE insertions

The majority of human genomic transposon sequences are inactive due to the accumulation of mutations and rearrangements that has occurred during evolution, as well as 5' truncations during their insertion that render L1 copies inactive. In the case of the former, these older elements are essentially 'fixed' in human populations today. With all this genomic clutter, identifying polymorphic elements and de novo somatic insertions requires directed strategies in order to identify younger, potentially active, transposon copies. Methods for identifying this complement of novel TE insertions have been described and are under rapid development as genomic methodologies continue to avail themselves (Figure 1).

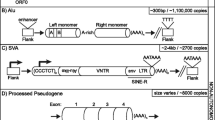

Techniques for identifying transposon insertions. (A) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays detect transposable element (TE) insertions. L1 display utilizes primers specific to particular subfamilies of LINE-1 elements. Using this method, candidate dimorphic L1 insertions have been identified. The ATLAS technique employs the principles of L1 display and suppression PCR. Genomic DNA is digested and ligated to oligonucleotide primers, and used as a template in a PCR reaction containing L1 and linker-specific primers. Primary PCR products are then used as templates in a linear PCR reaction containing a radiolabelled subfamily-specific L1 primer. Radiolabelled products are detected by electrophoresis and autoradiography. (B) A comparative genomics approach to identify TE insertions and deletions is depicted. For example, the completion of the draft chimpanzee genome sequence provided an opportunity to identify recently mobilized transposons in humans and chimpanzees. If a transposon insertion is present in only one of the two genomes, it is inferred that the insertion occurred since the existence of their most common recent ancestor (~6 million years ago). (C) A paired-end mapping approach is shown. This method entails generating paired-ends of several kilobase fragments, which are sequenced using next generation sequencing methodologies. Differences between the paired-end reads and a reference genomic region reveal the presence of structural variation. Simple insertions and deletions can be detected using this method. (D) A next generation sequencing method is shown. Selective amplification of the 3' end of a transposon is performed followed by deep sequencing. This short-read sequencing approach is able to detect precise insertion positions. (E) Microrray-based methods involve the hybridization of ligation-mediated PCR products to genomic tiling arrays. Specifically, vectorettes are ligated to restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA. The amplified fragments include the 3' end of a transposon sequence and unique flanking genomic DNA. These amplicons are hybridized to genomic tiling microarrays.

First generation methods for recovery of novel TEs

Many of the first assays for mobile elements were PCR-based and reliant on gel-based amplicon separation to distinguish the presence or absence of a particular element. Examples include a subtractive suppression PCR assay termed amplification typing of L1 active subfamilies (ATLAS) [75], a random decamer PCR called L1 display [76] and a ligation-mediated PCR called L1 insertion dimorphisms identification by PCR (LIDSIP) [77]. These techniques exploited sequences specific to young L1 families and gave investigators the first insights into the impressive degree of L1 polymorphism in humans. However, they did not lend themselves readily to comprehensive L1 mapping in large numbers of samples.

Mining genomic sequencing data for TE insertions

Analyses of genomic sequencing data have since contributed significantly to our understanding of polymorphic retroelements in humans, which will presumably accelerate with the ongoing exponential increases in available data. In silico mining of the human genome draft [78, 79], the Venter genome [80] and comparative sequence analysis of the human and chimpanzee genomes have been performed in order to detect species-specific transposon insertions [81–83]. These studies have revealed that subfamilies of Alu, LINE-1 and SVA elements have differentially amplified in humans and chimpanzees. Building on the foundation of the human reference genome, relatively new concerted efforts are underway which may harness sequencing methods to provide insights into structural variation. Paired-end mapping of size selected DNA fragments represents a large-scale approach to identify sizable variants in the genome. For example, using this method with fragments cloned into fosmids, it is possible to detect large insertions and deletions (indels) embedded in repetitive DNA [84, 85]. Beck and colleagues recently showed this is a powerful means of identify young, polymorphic full-length L1 s, which are high in retrotransposition activity [86]. Moreover, this method appears to effectively identify the source of parent elements responsible for ongoing L1 insertions in human populations today.

High throughput TE mapping methods

Technologic developments in sequencing methods and microarray platforms are expanding methods for high throughput TE discovery in the post-genomic era. Several laboratories recently published targeted methods for recovering TE insertion sites that, in combination with high resolution microarrays or deep sequencing, allow researchers to catalogue novel transposition events on a genome-wide basis [63, 87–89]. For example, with the Boeke laboratory, we approached L1(Ta) mapping in the human genome using a ligation mediated PCR method known as vectorette PCR [88]. In this method, non-complementary oligonucleotides are ligated to DNA ends and serve to bind a PCR primer only after first strand synthesis is initiated from the L1(Ta). The result is an amplification of unique genomic DNA adjacent to the mobile element. Individual insertion sites can be recognized in this complex mixture of amplicons by labelling and hybridizing to genomic tiling microarrays or by deep sequencing. These data suggest that the rate of new L1 insertions in humans is nearly double previous estimates, with non-parental integrations occurring in nearly 1/100 births, a finding that agrees well with data recently described by Kazazian and colleagues [87]. These types of approaches will undoubtedly be useful in detecting novel TE insertions in both normal individuals and in patients affected with genetic diseases in the future.

TEs and human genetic variation

To what extent do mobile elements contribute to human genetic diversity? This is a complex question, which is just beginning to be explored in greater depth. Sequencing of the human genome revealed that individual genomes typically exhibit 0.1% variation [2]. Most of the individual genome variation can be attributed to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), chromosome rearrangements, copy number variants and repetitive elements. The Human Genome Project revealed that there are 2000 polymorphic L1 elements and 7000 polymorphic Alus in humans, although it is postulated that the actual number is significantly higher due to ongoing transposition and individual TE polymorphisms. In an effort to detect the degree of genetic variation that is caused by transposable elements, Bennett and colleagues [90] analysed DNA re-sequencing data from 36 people of diverse ancestry. Indel polymorphisms were screened in order to find those that were caused by de novo transposon insertions. They estimated that human populations harbour an average estimated 2000 common transposon insertion polymorphisms. In general, these results are consistent with several other studies regarding Alu element polymorphisms [8] and L1-Hs insertion polymorphisms [75, 76, 78, 91, 92].

In an attempt to identify the number of active polymorphic L1 elements in the human genome, Brouha and colleagues [91] identified 86 young, full-length L1 elements from an early draft of the human genome sequence. Of these, they determined that 38 (44%) are polymorphic for presence in the human genome. In addition, a similar number of elements were identified to be active in a cell-culture based retrotransposition assay. Based on these results, it is estimated that there are 80-100 active L1 s in the average diploid genome. Of these, in vitro retrotransposition assays suggest only a small number are highly active and have accounted for the majority of de novo insertions [91].

Recently, several groups have focused their efforts on determining what fraction of structural variants (SVs) in the human genome is due to TE sequences. Korbel and colleagues [84] employed a paired-end mapping technique to identify ~1000 SVs and reported that the number of these variants in humans is significantly higher that originally appreciated. Xing et al. [80] analysed ~8000 SVs with the goal of identifying those that are associated with mobile elements. Computational analyses and experimental validation revealed that roughly 700 novel transposable element insertion events due to Alus, L1 elements and SVAs are found in an individual diploid genome. Transposon-mediated deletions were also detected. The Jorde laboratory recently demonstrated that the presence of a fixed Alu insertion is predictive of an elevated local recombination rate, which may further contribute to non-allelic recombination events [93]. Indeed, it has become increasingly apparent that TEs play an important role in the generation of structural variants between individuals and this is an exciting area ripe for further study. Future efforts focused on characterizing the full extent of mobile element associated structural variants and probing their potential functional consequences are warranted.

Conclusions

Our understanding of the basic biology of TEs has expanded dramatically in the 60 years since their initial discovery. Yet, there are still many open questions awaiting further study. For example, the mechanisms of transposon regulation and mobilization in the germline and somatic cells have not been fully elucidated. If we appreciate where, when and how these processes occur, we will ultimately better understand the impact of these elements on host genomes and the extent to which they contribute to diversity.

Although major advances have been made in the identification of transposon insertions in humans, we are at the very earliest stages of recognizing the full implications of these findings. It is clear that TE insertions provide a rich source of inter-individual genetic variation. With the continued optimization of technologies that are able to identify all transposon insertions, we will undoubtedly gain a better understanding of the extent of TE diversity in individual genomes, in human populations and in disease states.

Abbreviations

- APOBEC:

-

apolipoprotein B messenger RNA editing enzyme

- No Term:

-

Catalytic polypeptide

- ATLAS:

-

amplification typing of L1 active subfamilies

- IAP:

-

intracisternal A particle

- indels:

-

insertions and deletions

- LINE:

-

long interspersed nucleotide element

- LTR:

-

long terminal repeat

- MAEL:

-

MAELSTROM

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- PIRNA:

-

piwi-interacting RNA

- SB DNA:

-

Sleeping Beauty DNA

- SINE:

-

short interspersed nucleotide element

- SV:

-

structured variant

- TE:

-

transposable element.

References

Ray DA, Feschotte C, Pagan HJ, Smith JD, Pritham EJ, Arensburger P, Atkinson PW, Craig NL: Multiple waves of recent DNA transposon activity in the bat, Myotis lucifugus. Genome Res. 2008, 18: 717-728. 10.1101/gr.071886.107.

Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W: Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001, 409: 860-921. 10.1038/35057062.

Luan DD, Korman MH, Jakubczak JL, Eickbush TH: Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell. 1993, 72: 595-605. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90078-5.

Feng Q, Moran JV, Kazazian HH, Boeke JD: Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell. 1996, 87: 905-916. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81997-2.

Cost GJ, Feng Q, Jacquier A, Boeke JD: Human L1 element target-primed reverse transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 2002, 21: 5899-5910. 10.1093/emboj/cdf592.

Cordaux R, Batzer MA: The impact of retrotransposons on human genome evolution. Nature Rev Genetics. 2009, 10: 691-703. 10.1038/nrg2640.

Belancio VP, Hedges DJ, Deininger P: Mammalian non-LTR retrotransposons: for better or worse, in sickness and in health. Genome Res. 2008, 18: 343-358. 10.1101/gr.5558208.

Batzer MA, Deininger PL: Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nature Rev Genetics. 2002, 3: 370-379. 10.1038/nrg798.

Bennett EA, Keller H, Mills RE, Schmidt S, Moran JV, Weichenrieder O, Devine SE: Active Alu retrotransposons in the human genome. Genome Res. 2008, 18: 1875-1883. 10.1101/gr.081737.108.

Cordaux R, Lee J, Dinoso L, Batzer MA: Recently integrated Alu retrotransposons are essentially neutral residents of the human genome. Gene. 2006, 373: 138-144. 10.1016/j.gene.2006.01.020.

Goodier JL, Kazazian HH: Retrotransposons revisited: the restraint and rehabilitation of parasites. Cell. 2008, 135: 23-35. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.022.

Volff JN: Turning junk into gold: domestication of transposable elements and the creation of new genes in eukaryotes. BioEssays: News Rev Molec Cellular Dev Biol. 2006, 28: 913-922.

Feschotte C: Transposable elements and the evolution of regulatory networks. Nature Rev Genetics. 2008, 9: 397-405. 10.1038/nrg2337.

Agrawal A, Eastman QM, Schatz DG: Transposition mediated by RAG1 and RAG2 and its implications for the evolution of the immune system. Nature. 1998, 394: 744-751. 10.1038/29457.

Hiom K, Melek M, Gellert M: DNA transposition by the RAG1 and RAG2 proteins: a possible source of oncogenic translocations. Cell. 1998, 94: 463-470. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81587-1.

Zhou L, Mitra R, Atkinson PW, Hickman AB, Dyda F, Craig NL: Transposition of hAT elements links transposable elements and V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2004, 432: 995-1001. 10.1038/nature03157.

Yoder JA, Walsh CP, Bestor TH: Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genetics. 1997, 13: 335-340. 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01181-5.

Martienssen RA, Colot V: DNA methylation and epigenetic inheritance in plants and filamentous fungi. Science NY. 2001, 293: 1070-1074.

Selker EU: Genome defense and DNA methylation in Neurospora. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quantitative Biol. 2004, 69: 119-124. 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.119.

Bourc'his D, Bestor TH: Meiotic catastrophe and retrotransposon reactivation in male germ cells lacking Dnmt3L. Nature. 2004, 431: 96-99. 10.1038/nature02886.

Belancio VP, Hedges DJ, Deininger P: LINE-1 RNA splicing and influences on mammalian gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34: 1512-1521. 10.1093/nar/gkl027.

Perepelitsa-Belancio V, Deininger P: RNA truncation by premature polyadenylation attenuates human mobile element activity. Nature Genetics. 2003, 35: 363-366. 10.1038/ng1269.

Chiu YL, Greene WC: The APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases: an innate defensive network opposing exogenous retroviruses and endogenous retroelements. Ann Rev Immunol. 2008, 26: 317-353. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090350.

Schumann GG: APOBEC3 proteins: major players in intracellular defence against LINE-1-mediated retrotransposition. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007, 35: 637-642. 10.1042/BST0350637.

Chiu YL, Greene WC: The APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases: an innate defensive network opposing exogenous retroviruses and endogenous retroelements. Ann Rev Immunol. 2008, 26: 317-353. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090350.

Robert VJ, Vastenhouw NL, Plasterk RH: RNA interference, transposon silencing, and cosuppression in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line: similarities and differences. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quantitative Biol. 2004, 69: 397-402. 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.397.

Soifer HS, Zaragoza A, Peyvan M, Behlke MA, Rossi JJ: A potential role for RNA interference in controlling the activity of the human LINE-1 retrotransposon. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33: 846-856. 10.1093/nar/gki223.

Yang N, Kazazian HH: L1 retrotransposition is suppressed by endogenously encoded small interfering RNAs in human cultured cells. Nature Structural Molec Biol. 2006, 13: 763-771. 10.1038/nsmb1141.

Aravin AA, Hannon GJ, Brennecke J: The Piwi-piRNA pathway provides an adaptive defense in the transposon arms race. Science NY. 2007, 318: 761-764.

Klattenhoff C, Theurkauf W: Biogenesis and germline functions of piRNAs. Development (Cambridge, England). 2008, 135: 3-9.

O'Donnell KA, Boeke JD: Mighty Piwis defend the germline against genome intruders. Cell. 2007, 129: 37-44. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.028.

Brennecke J, Aravin AA, Stark A, Dus M, Kellis M, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ: Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2007, 128: 1089-1103. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.043.

Gunawardane LS, Saito K, Nishida KM, Miyoshi K, Kawamura Y, Nagami T, Siomi H, Siomi MC: A slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5' end formation in Drosophila. Science NY. 2007, 315: 1587-1590.

Houwing S, Kamminga LM, Berezikov E, Cronembold D, Girard A, van den Elst H, Filippov DV, Blaser H, Raz E, Moens CB, Plasterk RH, Hannon GJ, Draper BW, Ketting RF: A role for Piwi and piRNAs in germ cell maintenance and transposon silencing in Zebrafish. Cell. 2007, 129: 69-82. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.026.

Malone CD, Hannon GJ: Small RNAs as guardians of the genome. Cell. 2009, 136: 656-668. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.045.

Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Watanabe T, Gotoh K, Totoki Y, Toyoda A, Ikawa M, Asada N, Kojima K, Yamaguchi Y, Ijiri TW, Hata K, Li E, Matsuda Y, Kimura T, Okabe M, Sakaki Y, Sasaki H, Nakano T: DNA methylation of retrotransposon genes is regulated by Piwi family members MILI and MIWI2 in murine fetal testes. Genes Dev. 2008, 22: 908-917. 10.1101/gad.1640708.

Carmell MA, Girard A, van de Kant HJ, Bourc'his D, Bestor TH, de Rooij DG, Hannon GJ: MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Developmental Cell. 2007, 12: 503-514. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.001.

Costa Y, Speed RM, Gautier P, Semple CA, Maratou K, Turner JM, Cooke HJ: Mouse MAELSTROM: the link between meiotic silencing of unsynapsed chromatin and microRNA pathway?. Hum Molec Genetics. 2006, 15: 2324-2334. 10.1093/hmg/ddl158.

Eddy EM: Germ plasm and the differentiation of the germ cell line. Int Rev Cytol. 1975, 43: 229-280. 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)60070-4.

Lim AK, Kai T: Unique germ-line organelle, nuage, functions to repress selfish genetic elements in Drosophila melanogaster. Proce Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104: 6714-6719. 10.1073/pnas.0701920104.

Soper SF, van der Heijden GW, Hardiman TC, Goodheart M, Martin SL, de Boer P, Bortvin A: Mouse maelstrom, a component of nuage, is essential for spermatogenesis and transposon repression in meiosis. Developmental Cell. 2008, 15: 285-297. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.015.

Ma L, Buchold GM, Greenbaum MP, Roy A, Burns KH, Zhu H, Han DY, Harris RA, Coarfa C, Gunaratne PH, Yan W, Matzuk MM: GASZ is essential for male meiosis and suppression of retrotransposon expression in the male germline. PLoS Genetics. 2009, 5: e1000635-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000635.

Kazazian HH, Wong C, Youssoufian H, Scott AF, Phillips DG, Antonarakis SE: Haemophilia A resulting from de novo insertion of L1 sequences represents a novel mechanism for mutation in man. Nature. 1988, 332: 164-166. 10.1038/332164a0.

Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH: Biology of mammalian L1 retrotransposons. Ann Rev Genetics. 2001, 35: 501-538. 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091032.

Rohrer J, Minegishi Y, Richter D, Eguiguren J, Conley ME: Unusual mutations in Btk: an insertion, a duplication, an inversion and four large deletions. Clin Immun Orlando. 1999, 90: 28-37. 10.1006/clim.1998.4629.

Holmes SE, Dombroski BA, Krebs CM, Boehm CD, Kazazian HH: A new retrotransposable human L1 element from the LRE2 locus on chromosome 1q produces a chimaeric insertion. Nature Genetics. 1994, 7: 143-148. 10.1038/ng0694-143.

Narita N, Nishio H, Kitoh Y, Ishikawa Y, Ishikawa Y, Minami R, Nakamura H, Matsuo M: Insertion of a 5' truncated L1 element into the 3' end of exon 44 of the dystrophin gene resulted in skipping of the exon during splicing in a case of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest. 1993, 91: 1862-1867. 10.1172/JCI116402.

Yoshida K, Nakamura A, Yazaki M, Ikeda S, Takeda S: Insertional mutation by transposable element, L1, in the DMD gene results in X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy. Hum Molec Genetics. 1998, 7: 1129-1132. 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1129.

Wallace MR, Andersen LB, Saulino AM, Gregory PE, Glover TW, Collins FS: A de novo Alu insertion results in neurofibromatosis type 1. Nature. 1991, 353: 864-866. 10.1038/353864a0.

Oldridge M, Zackai EH, McDonald-McGinn DM, Iseki S, Morriss-Kay GM, Twigg SR, Johnson D, Wall SA, Jiang W, Theda C: De novo alu-element insertions in FGFR2 identify a distinct pathological basis for Apert syndrome. Am J Hum Genetics. 1999, 64: 446-461. 10.1086/302245.

Bochukova EG, Roscioli T, Hedges DJ, Taylor IB, Johnson D, David DJ, Deininger PL, Wilkie AO: Rare mutations of FGFR2 causing apert syndrome: identification of the first partial gene deletion, and an Alu element insertion from a new subfamily. Hum Mutation. 2009, 30: 204-211. 10.1002/humu.20825.

Callinan PA, Batzer MA: Retrotransposable elements and human disease. Genome Dynamics. 2006, 1: 104-115. full_text.

Konkel MK, Batzer MA: A mobile threat to genome stability: the impact of non-LTR retrotransposons upon the human genome. Seminars Cancer Biol. 2010,

Belancio VP, Roy-Engel AM, Pochampally RR, Deininger P: Somatic expression of LINE-1 elements in human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38: 3909-3922. 10.1093/nar/gkq132.

Kubo S, Seleme MC, Soifer HS, Perez JL, Moran JV, Kazazian HH, Kasahara N: L1 retrotransposition in nondividing and primary human somatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103: 8036-8041. 10.1073/pnas.0601954103.

Kano H, Godoy I, Courtney C, Vetter MR, Gerton GL, Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH: L1 retrotransposition occurs mainly in embryogenesis and creates somatic mosaicism. Genes Development. 2009, 23: 1303-1312. 10.1101/gad.1803909.

van den Hurk JA, Meij IC, Seleme MC, Kano H, Nikopoulos K, Hoefsloot LH, Sistermans EA, de Wijs IJ, Mukhopadhyay A, Plomp AS, de Jong PT, Kazazian HH, Cremers FP: L1 retrotransposition can occur early in human embryonic development. Hum Mol Genet. 2007, 16: 1587-1592. 10.1093/hmg/ddm108.

An W, Han JS, Wheelan SJ, Davis ES, Coombes CE, Ye P, Triplett C, Boeke JD: Active retrotransposition by a synthetic L1 element in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006, 103: 18662-18667. 10.1073/pnas.0605300103.

Muotri AR, Chu VT, Marchetto MC, Deng W, Moran JV, Gage FH: Somatic mosaicism in neuronal precursor cells mediated by L1 retrotransposition. Nature. 2005, 435: 903-910. 10.1038/nature03663.

Coufal NG, Garcia-Perez JL, Peng GE, Yeo GW, Mu Y, Lovci MT, Morell M, O'Shea KS, Moran JV, Gage FH: L1 retrotransposition in human neural progenitor cells. Nature. 2009, 460: 1127-1131. 10.1038/nature08248.

Goodier JL, Zhang L, Vetter MR, Kazazian HH: LINE-1 ORF1 protein localizes in stress granules with other RNA-binding proteins, including components of RNA interference RNA-induced silencing complex. Molec Cellular Biol. 2007, 27: 6469-6483. 10.1128/MCB.00332-07.

Miki Y, Nishisho I, Horii A, Miyoshi Y, Utsunomiya J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Nakamura Y: Disruption of the APC gene by a retrotransposal insertion of L1 sequence in a colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1992, 52: 643-645.

Iskow RC, McCabe MT, Mills RE, Torene S, Pittard WS, Neuwald AF, Van Meir EG, Vertino PM, Devine SE: Natural mutagenesis of human genomes by endogenous retrotransposons. Cell. 141: 1253-1261. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.020.

Belancio VP, Roy-Engel AM, Deininger P: The impact of multiple splice sites in human L1 elements. Gene. 2008, 411: 38-45. 10.1016/j.gene.2007.12.022.

Su Y, Davies S, Davis M, Lu H, Giller R, Krailo M, Cai Q, Robison L, Shu XO: Expression of LINE-1 p40 protein in pediatric malignant germ cell tumors and its association with clinicopathological parameters: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer Lett. 2007, 247: 204-212. 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.04.010.

Bratthauer GL, Cardiff RD, Fanning TG: Expression of LINE-1 retrotransposons in human breast cancer. Cancer. 1994, 73: 2333-2336. 10.1002/1097-0142(19940501)73:9<2333::AID-CNCR2820730915>3.0.CO;2-4.

Howard G, Eiges R, Gaudet F, Jaenisch R, Eden A: Activation and transposition of endogenous retroviral elements in hypomethylation induced tumors in mice. Oncogene. 2008, 27: 404-408. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210631.

Lin C, Yang L, Tanasa B, Hutt K, Ju BG, Ohgi K, Zhang J, Rose DW, Fu XD, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG: Nuclear receptor-induced chromosomal proximity and DNA breaks underlie specific translocations in cancer. Cell. 2009, 139: 1069-1083. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.030.

Dupuy AJ, Akagi K, Largaespada DA, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA: Mammalian mutagenesis using a highly mobile somatic Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Nature. 2005, 436: 221-226. 10.1038/nature03691.

Collier LS, Carlson CM, Ravimohan S, Dupuy AJ, Largaespada DA: Cancer gene discovery in solid tumours using transposon-based somatic mutagenesis in the mouse. Nature. 2005, 436: 272-276. 10.1038/nature03681.

Starr TK, Allaei R, Silverstein KA, Staggs RA, Sarver AL, Bergemann TL, Gupta M, O'Sullivan MG, Matise I, Dupuy AJ, Collier LS, Powers S, Oberg AL, Asmann YW, Thibodeau SN, Tessarollo L, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Cormier RT, Largaespada DA: A transposon-based genetic screen in mice identifies genes altered in colorectal cancer. Science. 2009, 323: 1747-1750. 10.1126/science.1163040.

Keng VW, Villanueva A, Chiang DY, Dupuy AJ, Ryan BJ, Matise I, Silverstein KA, Sarver A, Starr TK, Akagi K, Tessarollo L, Collier LS, Powers S, Lowe SW, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Llovet JM, Largaespada DA: A conditional transposon-based insertional mutagenesis screen for genes associated with mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Biotechnol. 2009, 27: 264-274. 10.1038/nbt.1526.

Han JS, Boeke JD: A highly active synthetic mammalian retrotransposon. Nature. 2004, 429: 314-318. 10.1038/nature02535.

An W, Han JS, Schrum CM, Maitra A, Koentgen F, Boeke JD: Conditional activation of a single-copy L1 transgene in mice by Cre. Genesis. 2008, 46: 373-383. 10.1002/dvg.20407.

Badge RM, Alisch RS, Moran JV: ATLAS: a system to selectively identify human-specific L1 insertions. Am J Hum Genetics. 2003, 72: 823-838. 10.1086/373939.

Sheen FM, Sherry ST, Risch GM, Robichaux M, Nasidze I, Stoneking M, Batzer MA, Swergold GD: Reading between the LINEs: human genomic variation induced by LINE-1 retrotransposition. Genome Res. 2000, 10: 1496-1508. 10.1101/gr.149400.

Pornthanakasem W, Mutirangura A: LINE-1 insertion dimorphisms identification by PCR. Biotechniques. 2004, 37: 750-752.

Myers JS, Vincent BJ, Udall H, Watkins WS, Morrish TA, Kilroy GE, Swergold GD, Henke J, Henke L, Moran JV, Jorde LB, Batzer MA: A comprehensive analysis of recently integrated human Ta L1 elements. Am J Hum Genetics. 2002, 71: 312-326. 10.1086/341718.

Salem AH, Myers JS, Otieno AC, Watkins WS, Jorde LB, Batzer MA: LINE-1 preTa elements in the human genome. J Molec Biol. 2003, 326: 1127-1146. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00032-9.

Xing J, Zhang Y, Han K, Salem AH, Sen SK, Huff CD, Zhou Q, Kirkness EF, Levy S, Batzer MA, Jorde LB: Mobile elements create structural variation: analysis of a complete human genome. Genome Res. 2009, 19: 1516-1526. 10.1101/gr.091827.109.

Mills RE, Bennett EA, Iskow RC, Luttig CT, Tsui C, Pittard WS, Devine SE: Recently mobilized transposons in the human and chimpanzee genomes. Am J Hum Genetics. 2006, 78: 671-679. 10.1086/501028.

Mills RE, Bennett EA, Iskow RC, Devine SE: Which transposable elements are active in the human genome?. Trends Genetics. 2007, 23: 183-191. 10.1016/j.tig.2007.02.006.

Watanabe H, Fujiyama A, Hattori M, Taylor TD, Toyoda A, Kuroki Y, Noguchi H, BenKahla A, Lehrach H, Sudbrak R: DNA sequence and comparative analysis of chimpanzee chromosome 22. Nature. 2004, 429: 382-388. 10.1038/nature02564.

Korbel JO, Urban AE, Affourtit JP, Godwin B, Grubert F, Simons JF, Kim PM, Palejev D, Carriero NJ, Du L, Taillon BE, Chen Z, Tanzer A, Saunders AC, Chi J, Yang F, Carter NP, Hurles ME, Weissman SM, Harkins TT, Gerstein MB, Egholm M, Snyder M: Paired-end mapping reveals extensive structural variation in the human genome. Science. 2007, 318: 420-426. 10.1126/science.1149504.

Kidd JM, Cooper GM, Donahue WF, Hayden HS, Sampas N, Graves T, Hansen N, Teague B, Alkan C, Antonacci F: Mapping and sequencing of structural variation from eight human genomes. Nature. 2008, 453: 56-64. 10.1038/nature06862.

Beck CR, Collier P, Macfarlane C, Malig M, Kidd JM, Eichler EE, Badge RM, Moran JV: LINE-1 retrotransposition activity in human genomes. Cell. 141: 1159-1170. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.021.

Ewing AD, Kazazian HH: High-throughput sequencing reveals extensive variation in human-specific L1 content in individual human genomes. Genome Res. 2010,

Huang CR, Schneider AM, Lu Y, Niranjan T, Shen P, Robinson MA, Steranka JP, Valle D, Civin CI, Wang T, Wheelan SJ, Ji H, Boeke JD, Burns KH: Mobile interspersed repeats are major structural variants in the human genome. Cell. 141: 1171-1182. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.026.

Witherspoon DJ, Xing J, Zhang Y, Watkins WS, Batzer MA, Jorde LB: Mobile element scanning (ME-Scan) by targeted high-throughput sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2010, 11: 410-10.1186/1471-2164-11-410.

Bennett EA, Coleman LE, Tsui C, Pittard WS, Devine SE: Natural genetic variation caused by transposable elements in humans. Genetics. 2004, 168: 933-951. 10.1534/genetics.104.031757.

Brouha B, Schustak J, Badge RM, Lutz-Prigge S, Farley AH, Moran JV, Kazazian HH: Hot L1 s account for the bulk of retrotransposition in the human population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 5280-5285. 10.1073/pnas.0831042100.

Ovchinnikov I, Troxel AB, Swergold GD: Genomic characterization of recent human LINE-1 insertions: evidence supporting random insertion. Genome Res. 2001, 11: 2050-2058. 10.1101/gr.194701.

Witherspoon DJ, Watkins WS, Zhang Y, Xing J, Tolpinrud WL, Hedges DJ, Batzer MA, Jorde LB: Alu repeats increase local recombination rates. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 530-10.1186/1471-2164-10-530.

Alves G, Tatro A, Fanning T: Differential methylation of human LINE-1 retrotransposons in malignant cells. Gene. 1996, 176: 39-44. 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00205-3.

Roman-Gomez J, Jimenez-Velasco A, Agirre X, Cervantes F, Sanchez J, Garate L, Barrios M, Castillejo JA, Navarro G, Colomer D, Prosper F, Heiniger A, Torres A: Promoter hypomethylation of the LINE-1 retrotransposable elements activates sense/antisense transcription and marks the progression of chronic myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2005, 24: 7213-7223. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208866.

Dante R, Dante-Paire J, Rigal D, Roizes G: Methylation patterns of long interspersed repeated DNA and alphoid repetitive DNA from human cell lines and tumors. Anticancer Res. 1992, 12: 559-563.

Estecio MR, Gharibyan V, Shen L, Ibrahim AE, Doshi K, He R, Jelinek J, Yang AS, Yan PS, Huang TH, Tajara EH, Issa JP: LINE-1 hypomethylation in cancer is highly variable and inversely correlated with microsatellite instability. PloS one. 2007, 2: e399-10.1371/journal.pone.0000399.

Suter CM, Martin DI, Ward RL: Hypomethylation of L1 retrotransposons in colorectal cancer and adjacent normal tissue. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004, 19: 95-101. 10.1007/s00384-003-0539-3.

Takai D, Yagi Y, Habib N, Sugimura T, Ushijima T: Hypomethylation of LINE1 retrotransposon in human hepatocellular carcinomas, but not in surrounding liver cirrhosis. Japanese J Clin Oncol. 2000, 30: 306-309. 10.1093/jjco/hyd079.

Choi IS, Estecio MR, Nagano Y, Kim do H, White JA, Yao JC, Issa JP, Rashid A: Hypomethylation of LINE-1 and Alu in well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (pancreatic endocrine tumors and carcinoid tumors). Modern Pathol. 2007, 20: 802-810. 10.1038/modpathol.3800825.

Cho NY, Kim BH, Choi M, Yoo EJ, Moon KC, Cho YM, Kim D, Kang GH: Hypermethylation of CpG island loci and hypomethylation of LINE-1 and Alu repeats in prostate adenocarcinoma and their relationship to clinicopathological features. J Pathol. 2007, 211: 269-277. 10.1002/path.2106.

Santourlidis S, Florl A, Ackermann R, Wirtz HC, Schulz WA: High frequency of alterations in DNA methylation in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Prostate. 1999, 39: 166-174. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19990515)39:3<166::AID-PROS4>3.0.CO;2-J.

Schulz WA, Elo JP, Florl AR, Pennanen S, Santourlidis S, Engers R, Buchardt M, Seifert HH, Visakorpi T: Genomewide DNA hypomethylation is associated with alterations on chromosome 8 in prostate carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002, 35: 58-65. 10.1002/gcc.10092.

Jurgens B, Schmitz-Drager BJ, Schulz WA: Hypomethylation of L1 LINE sequences prevailing in human urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996, 56: 5698-5703.

Florl AR, Lower R, Schmitz-Drager BJ, Schulz WA: DNA methylation and expression of LINE-1 and HERV-K provirus sequences in urothelial and renal cell carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1999, 80: 1312-1321. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690524.

Neuhausen A, Florl AR, Grimm MO, Schulz WA: DNA methylation alterations in urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Biol Therapy. 2006, 5: 993-1001. 10.4161/cbt.5.8.2885.

Acknowledgements

We thank N Craig and L Dai for their insightful comments. KAO is a fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation. KHB is supported by a K08 award from the National Cancer Institute and a career award for medical scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KAO and KHB wrote the review. Both authors approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

O'Donnell, K.A., Burns, K.H. Mobilizing diversity: transposable element insertions in genetic variation and disease. Mobile DNA 1, 21 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1759-8753-1-21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1759-8753-1-21