Abstract

Introduction

Chondrosarcoma is well-known to be primarily resistant to conventional radiation and chemotherapy.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 32-year-old Caucasian man with clear cell chondrosarcoma who presented with symptomatic recurrence in his pelvis and metastases to his skull and lungs. Our patient underwent systemic therapy with sunitinib and then consolidation with proton beam radiation to his symptomatic site. He achieved complete symptomatic relief with a significantly improved performance status and had an almost complete and durable metabolic response on fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography.

Conclusions

Our findings have important clinical implications and suggest novel clinical trials for this difficult to treat disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chondrosarcomas are malignant tumors that arise from cartilaginous tissue and comprise four major subtypes: mesenchymal, clear cell, conventional and dedifferentiated [1, 2]. In about half of cases, tumors develop from large bones of the lower extremities and in one-fifth, disease is metastatic upon presentation. Except for the mesenchymal subtype, chondrosarcomas are primarily resistant to conventional radiation and chemotherapy [1, 3, 4]. Surgical resection remains the primary treatment option [5]. For patients with unresectable disease, the prognosis is dismal and symptoms can be debilitating due to sites of disease involvement.

Recent advances in the molecular understanding of sarcomas and the development of targeted therapy for sarcoma treatment have led to interest in the possibility of testing targeted agents in chondrosarcomas [6]. Gene expression profiling has identified high levels of tyrosine kinase and receptor tyrosine kinase expression in a number of sarcoma types, indicating that sarcomas may potentially be candidates for therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors [7–14]. In chondrosarcoma, the platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) tyrosine kinase pathway has also been shown to be activated, as evidenced by the overexpression of both PDGFR-α and -β and increased PDGFR signaling activity [15, 16]. Due to its inhibition of the PDGFR tyrosine kinase pathway, we hypothesize that sunitinib would have beneficial activity in chondrosarcoma.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 32-year-old Caucasian man who initially presented five years previously with right hip pain and was found at that time to have a large multilobulated mass arising from his right ilium and extending to his right sacrum with involvement of his gluteal musculature (Figure 1A). A biopsy showed a grade 1 chondrosarcoma. Subsequently, a right hemipelvectomy was performed, and the diagnosis of grade 1 chondrosarcoma arising from a pre-existing osteochondroma was confirmed (Figure 2A). Additionally, a minor component of clear cell chondrosarcoma was identified at the origin of the osteochondroma within the medullary cavity of the underlying ileum (Figure 2B). Recurrence in the sacral stump and an area adjacent to his paraspinous muscles was noted two years later after our patient experienced a fall. He underwent proton beam radiotherapy and resection, complicated by a postsurgical abscess.

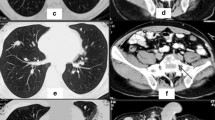

Representative scans done upon diagnosis and during the course of sunitinib treatment. (A) Diagnostic computed tomography showing the multilobulated chondrosarcoma mass arising from his right pelvis. (B) Superimposed fluorine-18- fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography and computed tomography scans showing the pelvis mass (white arrow) immediately prior to sunitinib, two months after initiation of sunitinib alone and two months after combined sunitinib and proton beam radiation. Intensity of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake: red, high; yellow, intermediate; blue, low.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of sections from our patient's pelvic tumor mass and skull metastasis. (A) Low-power photomicrograph demonstrating the low-grade chondrosarcoma (black arrows) arising in the stalk of a pre-existing osteochondroma (white arrows). (B) Focally within the stalk of the osteochondroma, the tumor had features of clear cell chondrosarcoma. (C) The skull metastasis consisted entirely of the clear cell chondrosarcoma component.

Approximately two-and-a-half years later, our patient presented with significant pain in his right pelvis, difficulty in ambulating and a decreased performance status due to pain. A bone scan showed uptake in his left temporal bone and an excisional biopsy confirmed recurrence of the clear cell chondrosarcoma (Figure 2C). A positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan showed uptake to an standardized uptake value (SUV) maximum of 9.0 in the right sacral lesion with two other areas of uptake in his pelvis (Figure 1B). Two non-hypermetabolic pulmonary nodules were also noted. Stereotactic radiosurgery was applied to the temporal bone lesion. Our patient was started on sunitinib 37.5 mg daily, which was initially tolerated well, with only mild fatigue. His pain greatly improved. A PET/CT scan obtained two months after the initiation of sunitinib showed improvement in the fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avidity of the lesions, with a right sacral lesion showing an SUV of 6.8 (Figure 1B). He continued to take sunitinib at the same dose and was referred for proton beam radiation to his right pelvis. He received twenty fractions of radiation concurrent with sunitinib 37.5 mg daily and experienced some diarrhea and worsening of an acneiform rash, but our patient wished to continue on the same dose given his excellent response with regards to the pain. A total of six months after initiating sunitinib, our patient continued to show improvement on imaging, with a PET/CT scan revealing stable non-hypermetabolic pulmonary nodules and improvement in the right sacral lesion with an SUV of 3.4 (Figure 1B). He did require a reduction in the dose 25 mg daily, however, due to the worsening acneiform rash and diarrhea.

Discussion

Sunitinib is a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that exhibits inhibitory activity against multiple targets including c-KIT, vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR; VEGFR1, VEGFR2 and VEGFR3), PDGFR-α and -β, fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-3, colony stimulating factor 1 receptor, and RET [17, 18]. Inhibition of these receptor tyrosine kinases blocks the transduction of signals important for tumor growth, survival and angiogenesis. Phase II and III clinical trials with sunitinib have shown clinical benefit, with significantly improved progression-free and overall survival in patients with imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) and advanced renal cell carcinoma [19, 20]. A phase II study showed that continuous use of sunitinib in advanced or metastatic non-GIST sarcomas produced a noteworthy metabolic response in many patients [11].

In a murine model, sunitinib was shown to be synergistic with radiation in increasing apoptosis in endothelial cells, enhancing destruction of the tumor vasculature and increasing time to tumor growth [21]. While tumors regrew rapidly after the discontinuation of sunitinib in this study, it was also shown that restarting sunitinib therapy resulted in further growth delays, suggesting that patients can benefit from maintenance therapy with sunitinib after the completion of radiation.

Kao et al. published results of a phase I study employing sunitinib concurrent with stereotactic radiation for patients with oligometastatic disease [22]. In the study, 21 patients with one to five sites of metastatic disease of any solid tumor type were treated with sunitinib, starting at 25 mg daily, with radiation to 40Gy in 10 fractions. The doses of both the radiation and the sunitinib were increased as tolerated, leading to a dosing recommendation for sunitinib with radiation at 37.5 mg daily. Sunitinib in conjunction with radiation yielded a complete response in 42% of the lesions, with a partial response in 17% and stable disease in 28%. At the last follow-up, 38% of these patients were without evidence of disease.

Conclusions

Our study is the first to show that sunitinib has beneficial activity in chondrosarcoma and may be safely combined with proton beam radiation therapy. Randomized phase II or III clinical trials are needed to assess the role of sunitinib in this disease and as a radiosensitizer.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Gelderblom H, Hogendoorn PC, Dijkstra SD, van Rijswijk CS, Krol AD, Taminiau AH, Bovee JV: The clinical approach towards chondrosarcoma. Oncologist. 2008, 13: 320-329. 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0237.

Chow WA: Update on chondrosarcomas. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007, 19: 371-376. 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32812143d9.

Onishi AC, Hincker AM, Lee FY: Surmounting chemotherapy and radioresistance in chondrosarcoma: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Sarcoma. 2011, 2011: 381564-

Riedel RF, Larrier N, Dodd L, Kirsch D, Martinez S, Brigman BE: The clinical management of chondrosarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2009, 10: 94-106. 10.1007/s11864-009-0088-2.

Weber KL, Pring ME, Sim FH: Treatment and outcome of recurrent pelvic chondrosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002, 397: 19-28.

Grignani G, Palmerini E, Stacchiotti S, Boglione A, Ferraresi V, Frustaci S, Comandone A, Casali PG, Ferrari S, Aglietta M: A phase 2 trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with recurrent nonresectable chondrosarcomas expressing platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha or -beta: An Italian Sarcoma Group study. Cancer. 2011, 117: 826-831. 10.1002/cncr.25632.

Chao J, Budd GT, Chu P, Frankel P, Garcia D, Junqueira M, Loera S, Somlo G, Sato J, Chow WA: Phase II clinical trial of imatinib mesylate in therapy of KIT and/or PDGFRalpha-expressing Ewing sarcoma family of tumors and desmoplastic small round cell tumors. Anticancer Res. 2010, 30: 547-552.

Katz D, Lazar A, Lev D: Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (MPNST): the clinical implications of cellular signalling pathways. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009, 11: e30-

Trojan A, Montemurro M, Kamel M, Kristiansen G: Successful PDGFR-{alpha}/{beta} targeting with imatinib in uterine sarcoma. Ann Oncol. 2009, 20: 1898-1899. 10.1093/annonc/mdp431.

Dewaele B, Floris G, Finalet-Ferreiro J, Fletcher CD, Coindre JM, Guillou L, Hogendoorn PC, Wozniak A, Vanspauwen V, Schoffski P, Marynen P, Vandenberghe P, Sciot R, Debiec-Rychter M: Coactivated platelet-derived growth factor receptor {alpha} and epidermal growth factor receptor are potential therapeutic targets in intimal sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2010, 70: 7304-7314. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1543.

George S, Merriam P, Maki RG, van den Abbeele AD, Yap JT, Akhurst T, Harmon DC, Bhuchar G, O'Mara MM, D'Adamo DR, Morgan J, Schwartz GK, Wagner AJ, Butrynski JE, Demetri GD, Keohan ML: Multicenter phase II trial of sunitinib in the treatment of nongastrointestinal stromal tumor sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 3154-3160. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9890.

Taniguchi E, Nishijo K, McCleish AT, Michalek JE, Grayson MH, Infante AJ, Abboud HE, Legallo RD, Qualman SJ, Rubin BP, Keller C: PDGFR-A is a therapeutic target in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene. 2008, 27: 6550-6560. 10.1038/onc.2008.255.

Shimizu A, O'Brien KP, Sjoblom T, Pietras K, Buchdunger E, Collins VP, Heldin CH, Dumanski JP, Ostman A: The dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans-associated collagen type Ialpha1/platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) B-chain fusion gene generates a transforming protein that is processed to functional PDGF-BB. Cancer Res. 1999, 59: 3719-3723.

McArthur GA, Demetri GD, van Oosterom A, Heinrich MC, Debiec-Rychter M, Corless CL, Nikolova Z, Dimitrijevic S, Fletcher JA: Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 866-873. 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.088.

Lagonigro MS, Tamborini E, Negri T, Staurengo S, Dagrada GP, Miselli F, Gabanti E, Greco A, Casali PG, Carbone A, Pierotti MA, Pilotti S: PDGFRalpha, PDGFRbeta and KIT expression/activation in conventional chondrosarcoma. J Pathol. 2006, 208: 615-623. 10.1002/path.1945.

Schrage YM, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, de Miranda NF, van Oosterwijk J, Taminiau AH, van Wezel T, Hogendoorn PC, Bovee JV: Kinome profiling of chondrosarcoma reveals SRC-pathway activity and dasatinib as option for treatment. Cancer Res. 2009, 69: 6216-6222. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4801.

Papaetis GS, Syrigos KN: Sunitinib: a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the era of molecular cancer therapies. BioDrugs. 2009, 23: 377-389. 10.2165/11318860-000000000-00000.

Christensen JG: A preclinical review of sunitinib, a multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with anti-angiogenic and antitumour activities. Ann Oncol. 2007, 18 (Suppl 10): x3-10.

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Kim ST, Chen I, Bycott PW, Baum CM, Figlin RA: Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 115-124. 10.1056/NEJMoa065044.

Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, Blackstein ME, Shah MH, Verweij J, McArthur G, Judson IR, Heinrich MC, Morgan JA, Desai J, Fletcher CD, George S, Bello CL, Huang X, Baum CM, Casali PG: Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006, 368: 1329-1338. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4.

Schueneman AJ, Himmelfarb E, Geng L, Tan J, Donnelly E, Mendel D, McMahon G, Hallahan DE: SU11248 maintenance therapy prevents tumor regrowth after fractionated irradiation of murine tumor models. Cancer Res. 2003, 63: 4009-4016.

Kao J, Packer S, Vu HL, Schwartz ME, Sung MW, Stock RG, Lo YC, Huang D, Chen SH, Cesaretti JA: Phase 1 study of concurrent sunitinib and image-guided radiotherapy followed by maintenance sunitinib for patients with oligometastases: acute toxicity and preliminary response. Cancer. 2009, 115: 3571-3580. 10.1002/cncr.24412.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the care of the patient and analyzed the data. JDR performed the histological examination of the tumor sections. JD and LHD drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dallas, J., Imanirad, I., Rajani, R. et al. Response to sunitinib in combination with proton beam radiation in a patient with chondrosarcoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports 6, 41 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-6-41

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-6-41