Abstract

Fragile states are home to a sixth of the world's population, and their populations are particularly vulnerable to infectious disease outbreaks. Timely surveillance and control are essential to minimise the impact of these outbreaks, but little evidence is published about the effectiveness of existing surveillance systems. We did a systematic review of the circumstances (mode) of detection of outbreaks occurring in 22 fragile states in the decade 2000-2010 (i.e. all states consistently meeting fragility criteria during the timeframe of the review), as well as time lags from onset to detection of these outbreaks, and from detection to further events in their timeline. The aim of this review was to enhance the evidence base for implementing infectious disease surveillance in these complex, resource-constrained settings, and to assess the relative importance of different routes whereby outbreak detection occurs.

We identified 61 reports concerning 38 outbreaks. Twenty of these were detected by existing surveillance systems, but 10 detections occurred following formal notifications by participating health facilities rather than data analysis. A further 15 outbreaks were detected by informal notifications, including rumours.

There were long delays from onset to detection (median 29 days) and from detection to further events (investigation, confirmation, declaration, control). Existing surveillance systems yielded the shortest detection delays when linked to reduced barriers to health care and frequent analysis and reporting of incidence data.

Epidemic surveillance and control appear to be insufficiently timely in fragile states, and need to be strengthened. Greater reliance on formal and informal notifications is warranted. Outbreak reports should be more standardised and enable monitoring of surveillance systems' effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Bank describes a fragile state as a country 'facing particularly severe development challenges such as weak institutional capacity, poor governance, political instability, and frequently ongoing violence or the legacy effects of past severe conflict' [1].

In 2009, 29 countries were considered fragile, comprising a sixth of the world's population [2, 3]. Fragile states generally feature poor health indicators, high malnutrition prevalence, scarcity of skilled health workers and worsening rates of extreme poverty [4–6]. Their populations are also highly vulnerable to infectious disease outbreaks, a reflection of inadequate government services and armed conflict-related phenomena such as forced displacement [7]. It has been suggested that most major epidemics worldwide occur in complex emergency and/or natural disaster settings [8].

Detection and early containment of outbreaks in these settings is also challenging, as highlighted by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative's recent setbacks in several fragile states, where genetic analysis has demonstrated previously undetected poliovirus transmission of one year or more duration [9]. Given the intensity of polio surveillance compared to other epidemic detection systems, it is plausible that many other disease outbreaks are detected late or not at all in these same settings.

The importance of epidemic surveillance is recognised, but there is a scarcity of evidence on optimal ways to detect outbreaks in the unique situations of fragile states, where routine health information systems are weak, diagnostic tools limited and resources for structured surveillance, such as training, sample transport and data transmission, very constrained. It has been suggested, at least for early warning systems in humanitarian emergencies, that emphasis should be placed on detecting alerts from health facilities or other informal sources (e.g. community informants and the media), rather than on analysis of weekly or other surveillance data, which often feature low completeness and timeliness, or high background noise due to non-specific case definitions [10]. So as to contribute to the evidence basis, we carried out a review of how outbreaks have been detected in 22 states that consistently met definitions of fragility over the past decade, and of the timeliness of alert and response processes.

Methods

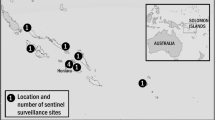

A systematic review of the published literature was performed to identify reports describing infectious disease outbreaks which began after 31st December 1999, within a predefined list of fragile states. The list of fragile states was created using the World Bank's quantitative definition, taking into account both the eligibility of a country to receive an interest-free International Development Association loan and a nation's Country Policy and Institutional Assessment score [11]. Countries which met this definition for at least ten out of eleven years from the year 2000 to 2010 (see Additional File 1) were included in this study [2, 12–15]. The final list of fragile states included in the review comprised Afghanistan, Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Liberia, Myanmar, the Republic of the Congo, Sao Tome et Principe, Sierra Leone, the Solomon Islands, Somalia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Timor-Leste, Togo and Zimbabwe.

Between 28th July 2010 and 23rd August 2010, a combined OVID SP search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE and Global Health databases was done. OVID SP is a search engine that taps into various literature databases relevant for global health. MEDLINE is a database of life sciences and biomedical journals. EMBASE is similar to MEDLINE but focuses on drug therapeutic studies. Global Health focuses on public health and medical science and includes conference abstracts, thesis reports, electronic information and other hard to find material. The basic search concepts were '(fragile state of interest) AND (epidemic-prone event) AND (detection)'. Each concept was expanded and variations of terms, including contemporary and historic, French and Spanish were included (see Additional File 1). Limitations applied were 'from 2000 to present' and 'humans'.

Outbreak descriptions were excluded from the search if they primarily involved foreign military forces, or if the disease of interest was HIV or poliomyelitis, due to the specific nature of surveillance for these two diseases.

Reports were included in the review if the circumstances of initial detection of the outbreak were reported; and/or if the time from onset to detection of the outbreak (determined using the definition in Table 1) could be calculated. Whenever this information was not clear based on the published report, we emailed the corresponding author once so as to solicit the missing information. We excluded the report if authors did not reply or could not provide the information requested.

For each eligible outbreak, the mode of detection was categorised into (i) data analysis if an existing surveillance system detected the outbreak by noticing a temporal increase in aggregate incidence, either above a pre-determined threshold or at levels considered unusual compared to the baseline; (ii) formal notification if the initial alert was raised by health workers as part of an ongoing surveillance system; and (iii) informal notification if the alert was raised through mechanisms other than an existing surveillance system, either by health workers or other community members. Both authors made this classification independently and came to a consensus decision on any discrepant choices.

Whenever available, we also calculated time lags from detection or onset to further events in the outbreak timeline, as per the definitions in Table 1.

Results

Search strategy results

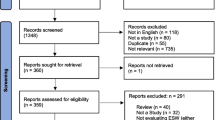

Of the 2634 abstracts produced by the search strategy, 58 reports describing 38 separate outbreaks were found eligible (Figure 1), of which 35 contained information about mode of detection and 24 about time from onset to detection and/or from detection to further events. Eleven outbreaks occurred in Sudan (including Southern Sudan), four each in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Guinea, three each in Afghanistan, Chad, Myanmar and the Republic of the Congo, and one each in Burundi, Liberia, the Central African Republic, Haiti, Somalia, Angola and Zimbabwe. The aetiologic agents included Vibrio cholerae (2), Plasmodium falciparum malaria (3), Neisseria meningitidis (2), measles virus (3), hepatitis E virus (2), Shigella dysenteriae type 1 (1), Leishmania donovani (1), yellow fever virus (7), dengue virus (1), Ebola virus (3), unspecified viral haemorrhagic fever (1), scurvy (1), Marburg virus (1), Escherichia coli (1), influenza virus (1), Yersinia pestis (1), Tunga penetrans (1), Gnathostoma spinigerum (1), monkeypox virus (1), Rift Valley fever virus (1), West Nile virus, Salmonella typhi (1), and Borrelia spp. (1).

Of the 58 reports included in the review, 20 were primarily authored by the World Health Organization; 14 by Médecins Sans Frontières; six by journalists; five by international research institutes; three by national research institutes; three by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; two by overseas governments; two by other NGOs; two by UNICEF; and one by the national government.

Mode of detection of outbreaks

Among the 35 outbreaks for which mode of detection information was available, 20 (57.1%) were detected through existing surveillance systems, with 10 detected by data analysis (Table 2) and 10 by formal notification (Table 3). Fifteen outbreaks (42.9%) were initially detected through informal notifications (Table 4). For three further outbreaks (yellow fever virus in Guinea, Bounouma subprefecture, August 2008 [16]; Salmonella typhi in central Myanmar, September 2000 [17]; Borrelia spp. relapsing fever in Southern Sudan, 2000 [18]), the mode of detection was unclear, but time to detection was available: these are included in the timeliness findings (see below).

Reports suggested that data analysis proved successful when there was frequent reporting and analysis of data, and with the provision of a free and dependable supply of medication (outbreaks 2, 8). Poor reporting practices delayed detection (outbreak 9). In two instances failures were compensated for by informal notifications after substantial delays (outbreaks 25, 35).

For both data analysis and formal notifications, limited access to and distrust of health services delayed detection (outbreaks 6, 7, 8, 19). In two instances, warnings provided by a geographic information system and detection of an outbreak amongst local wildlife led to enhanced surveillance and eventually detection (outbreaks 16, 33).

Informal notifications originated from a local non-governmental organisation (NGO) (outbreak 27), a research institute (outbreak 26), an embassy (outbreak 30), a UN radio operator (outbreak 21), a rumour received by the WHO (outbreak 33), international NGOs (outbreaks 22, 25, 31, 34), national hospital staff (outbreaks 23, 24, 28, 32). Again, treatment charges and limited access to health facilities delayed detection (outbreaks 25, 27). Four outbreaks occurring within isolated rural communities were associated with late detections (outbreaks 21, 22, 29, 34).

Timeliness of detection and other events

Overall, the median lag time from onset to detection was 29 days (range 7-80) in 16 outbreaks for which this information was available. In two cases, investigation also unveiled previously undetected and undiagnosed outbreaks due to the same agent. Outbreaks detected through informal notifications appeared to feature the longest detection delays (Figure 2).

From the date of detection, further median (range) delays were 7 days (0-30) to investigation, 23 (5-42) to confirmation, 30 (15-50) to declaration and 55 (26-154) to start of control (reactive vaccination). Numbers were small and no obvious pattern emerged according to the aetiologic agent's route of transmission (Figure 3), but long delays were obvious for some vector-borne disease outbreaks.

Considering the time since reported onset of the outbreak, delays were longer: 42 days (8-87) to investigation in nine outbreaks for which both time to detection and time from detection to investigation were available; 53 (14-71, five outbreaks) to confirmation; 56 (36-61, three outbreaks) to declaration; and 80 (78-86, three outbreaks) to control.

Early warning alert and response network (EWARN) systems set up in southern Sudan and Darfur in 2000 and 2004 respectively, were involved in six Sudanese outbreaks. These outbreaks generally featured the shortest times from onset through to confirmation (outbreaks 6, 9, 17, 18, 20, 38).

Cooperation by communities was greatly hampered by fear and distrust of control teams and biomedical interventions during investigations of Ebola virus and Marburg virus outbreaks (outbreaks 16, 23, 31). Other obstacles to investigation included poor road conditions and insecurity (outbreaks 31, 26, 33). On two occasions, misconceptions by authorities and subsequently late investigations significantly delayed confirmation of causative agents (outbreaks 2, 19).

Discussion and conclusions

This review suggests that over the last decade surveillance systems have played a considerable role in early outbreak detection in the 22 fragile states included in the review. However, on the whole data analysis seemed to lead to a minority of outbreak detections, with both formal and informal notifications of alerts playing a more prominent, though less timely role. Certain elements of the system played an important role in sensitivity and timeliness, including reduced barriers to health facility utilisation and frequent data analysis. Combining knowledge of the seasonal outbreak risks particular to each area with predictive tools such as geographic information systems could be used to improve the effectiveness of such systems. More importantly, surveillance systems in fragile states should enhance the detection of alerts outside routine data analysis, by focussing more efforts on building both formal and informal networks of informants, particularly where acute emergency conditions or remoteness prevent sophisticated data collection and analysis.

Our review suggested that timeliness of detection, investigation and response is poor for most outbreaks occurring in fragile states, with up to five months elapsing until the start of meaningful control. These delays negate most of the advantages of surveillance and make containment extremely difficult.

Our review is limited by our search strategy, which did not capture outbreaks described in the grey literature. Furthermore, findings may not apply to other states that met fragility criteria for only some of the years within the review's timeframe. Publication bias is likely to influence our findings, but its direction is difficult to gauge: while large outbreaks that were intensively investigated and controlled are more likely to be the subject of publications, small outbreaks that were detected early and contained are probably under-reported. We noted that the vast majority of reports included were authored by institutions based outside the affected countries, with only one report coming from the national ministry of health. This suggests a need to strengthen capacity by fragile states to communicate outbreak surveillance findings, so as to promote ownership of surveillance and outbreak control, and raise the profile of outbreaks and epidemic-prone diseases that international counterparts would not otherwise respond to.

During data abstraction, the considerable heterogeneity of formats and variables included in outbreak reports was apparent. We recommend that a more standardised format be introduced for papers reporting outbreaks, particularly affecting vulnerable populations; and that key meta-data such as the dates of salient events in the outbreak timeline and the circumstances of detection always be reported, so as to enable ongoing global monitoring of the effectiveness of surveillance systems and outbreak control interventions.

Abbreviations

- DRC:

-

Democratic Republic of Congo

- EWARN:

-

Early Warning Alert and Response Network

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- MSF:

-

Médecins Sans Frontières

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization.

References

IDA15 Operational Approaches and Financing in Fragile States. 2007, International Development Association

International Development Association, World Bank: 2009 IDA Country performance ratings (CPR) and components. Volume 2010. 2009, International Development Association, [http://siteresources.worldbank.org/IDA/Resources/73153-1181752621336/3878278-1277851499224/ICPR_2009_Alpha_Table1.pdf]

Ensuring fragile states are not left behind, summary report. 2009, Development Co-operation Directorate, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Global monitoring report 2007 - millennium development goals: report overview. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank

Meeting the health MDGs in fragile states. Health and fragile states. Volume. Edited by: ELDIS: ELDIS. 2010, [http://www.eldis.org/go/topics/dossiers/health-and-fragile-states/introduction-health-in-fragile-states/meeting-the-health-mdgs-in-fragile-states]

Human resources for health. Health and fragile states. Volume. Edited by: ELDIS: ELDIS. 2010, [http://www.eldis.org/go/topics/dossiers/health-and-fragile-states/who-health-systems-building-blocks/human-resources-for-health]

Bornemisza O, Ranson MK, Poletti TM, Sondorp E: Promoting health equity in conflict-affected fragile states. Social Science and Medicine. 2010, 70 (1): 80-88. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.032.

Spiegel PB, Phuoc L, Ververs MT, Salama P: Occurrence and overlap of natural disasters, complex emergencies and epidemics during the past decade (1995-2004). Conflict and Health. 2007, 1 (2): 1 March 2007

Global update on vaccine-derived polioviruses, January 2006-August 2007. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2007, 82 (39): 337-343.

Early warning surveillance and response in emergencies: WHO technical workshop, December 2009. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2010, 85 (14/15): 129-136.

The World Bank Group: Definitions of fragility and conflict. Fragile and conflict affected countries. Volume. Edited by: The World Bank Group. 2010, Washington, DC, [http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/PROJECTS/STRATEGIES/EXTLICUS/0,,contentMDK:22230573~pagePK:64171531~menuPK:4448982~piPK:64171507~theSitePK:511778,00.html]

International Development Association, World Bank: 2008 IDA country performance ratings and components, ranked by CPR. Volume 2010. 2008, International Development Association, [http://siteresources.worldbank.org/IDA/Resources/73153-1181752621336/3878278-1213817150625/Table2CPRRanked2008.pdf]

International Development Association, The World Bank: Harmonized list of fragile situations, Fiscal Year 2010. Volume. Edited by: The World Bank. 2010, [http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTLICUS/Resources/511777-1269623894864/Fragile_Situations_List_FY10_Mar_26_2010_EXT.pdf]

Independent Evaluation Group, The World Bank Group: Which countries are LICUS?. Engaging with fragile states. 2010, The World Bank Group

CPIA quintile of IDA-eligible countries, 2000-2004. International Development Association, World Bank

Outbreak news. Yellow fever, Guinea. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire/Section d'hygiene du Secretariat de la Societe des Nations = Weekly epidemiological record/Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. 2008, 83 (40): 358-359.

Aye TT, Siriarayapon P: Typhoid fever outbreak in Madaya Township, Mandalay Division, Myanmar, September 2000. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2004, 87 (4): 395-399.

Early warning and response network (EWARN), southern Sudan. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire/Section d'hygiene du Secretariat de la Societe des Nations = Weekly epidemiological record/Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. 2002, 77 (4): 26-27.

Kakar F, Ahmadzai AH, Habib N, Taqdeer A, Hartman AF: A successful response to an outbreak of cholera in Afghanistan. Tropical Doctor. 2008, 38 (1): 17-20. 10.1258/td.2006.006336.

Checchi F, Cox J, Balkan S, Tamrat A, Priotto G, Alberti KP, Guthmann J-P: Malaria epidemics and interventions, Kenya, Burundi, southern Sudan, and Ethiopia, 1999-2004. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006, 12 (10): 1477-1485.

Guthmann JP, Bonnet M, Ahoua L, Dantoine F, Balkan S, Van Herp M, Tamrat A, Legros D, Brown V, Checchi F: Death rates from malaria epidemics, Burundi and Ethiopia. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007, 13 (1): 140-143. 10.3201/eid1301.060546.

Protopopoff N, Van Herp M, Maes P, Reid T, Baza D, D'Alessandro U, Van Bortel W, Coosemans M: Vector control in a malaria epidemic occurring within a complex emergency situation in Burundi: a case study. Malaria Journal. 2007, 6: 93-10.1186/1475-2875-6-93.

Garcia V, Morel B, Wadack MA, Banguio M, Moulia-Pelat JP, Richard V: Outbreak of meningitis in the province of Logone occidental (Chad): descriptive study using health ministry data from 1998 to 2001. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique. 2004, 97 (3): 183-188.

Epidemics of meningococcal disease. African meningitis belt, 2001. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2001, 76 (37): 282-288.

Grais RF, De Radigues X, Dubray C, Fermon F, Guerin PJ: Exploring the time to intervene with a reactive mass vaccination campaign in measles epidemics. Epidemiology and Infection. 2006, 134 (4): 845-849. 10.1017/S0950268805005716.

Hepatitis E, Sudan--update. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire/Section d'hygiene du Secretariat de la Societe des Nations = Weekly epidemiological record/Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. 2004, 79 (38): 341-342.

Boccia D, Guthmann J-P, Klovstad H, Hamid N, Tatay M, Ciglenecki I, Nizou J-Y, Nicand E, Guerin PJ: High mortality associated with an outbreak of hepatitis E among displaced persons in Darfur, Sudan. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006, 42 (12): 1679-1684. 10.1086/504322.

Guthmann J-P, Klovstad H, Boccia D, Hamid N, Pinoges L, Nizou J-Y, Tatay M, Diaz F, Moren A, Grais RF: A large outbreak of hepatitis E among a displaced population in Darfur, Sudan, 2004: the role of water treatment methods. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006, 42 (12): 1685-1691. 10.1086/504321.

Coronado F, Musa N, El-Tayeb SAE, Haithami S, Dabbagh A, Mahoney F, Nandy R, Cairns L: Retrospective measles outbreak investigation: Sudan, 2004. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2006, 52 (5): 329-334. 10.1093/tropej/fml026.

Walden VM, Lamond E-A, Field SA: Container contamination as a possible source of a diarrhoea outbreak in Abou Shouk camp, Darfur province, Sudan. Disasters. 2005, 29 (3): 213-221. 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00287.x.

Das P: Infectious disease surveillance update. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2002, 2 (12): 716.

Moszynski P: Health organisation warns that kala-azar has returned to South Sudan. Lancet. 2002, 360 (9346): 1672.

Ritmeijer K, Davidson RN: Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene joint meeting with Medecins Sans Frontieres at Manson House, London, 20 March 2003: field research in humanitarian medical programmes. Medecins Sans Frontieres interventions against kala-azar in the Sudan, 1989-2003. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene. 2003, 97 (6): 609-613. 10.1016/S0035-9203(03)80047-0.

The yellow fever situation in Africa and South America in 2004. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2005, 80 (29): 250-256.

Yellow fever in Africa and South America, 2006. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire/Section d'hygiene du Secretariat de la Societe des Nations = Weekly epidemiological record/Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. 2008, 83 (8): 60-76.

Outbreak news: yellow fever, Guinea. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2009, 84 (4): 29-36.

Hlaing Myat T, Lowry K, Thein Thein M, Than Nu S, Aye Maung H, Kyu Kyu K, Kyaw Zin T, Soe T, Aaskov J: Myanmar dengue outbreak associated with displacement of serotypes 2, 3, and 4 by dengue 1. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004, 10 (4): 593-597.

Arthur RR: Ebola in Africa--discoveries in the past decade. Euro Surveillance: Bulletin Europeen sur les Maladies Transmissibles = European Communicable Disease Bulletin. 2002, 7 (3): 33-36.

Formenty P, Leroy EM, Epelboin A, Libama F, Lenzi M, Sudeck H, Yaba P, Allarangar Y, Boumandouki P, Nkounkou VB: Detection of Ebola virus in oral fluid specimens during outbreaks of Ebola virus hemorrhagic fever in the Republic of Congo. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006, 42 (11): 1521-1526. 10.1086/503836.

Formenty P, Libama E, Epelboin A, Allarangar Y, Leroy E, Moudzeo H, Tarangonia P, Molamou A, Lenzi M, Ait-Ikhlef K: L'epidemie de fievre hemorragique a virus ebola en Republique du Congo, 2003: une nouvelle strategie?. Medecine Tropicale. 2003, 63 (3): 291-295.

Onyango CO, Grobbelaar AA, Gibson GVF, Sang RC, Sow A, Swaneopel R, Burt FJ: Yellow fever outbreak, southern Sudan, 2003. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004, 10 (9): 1668-1670.

Onyango CO, Ofula VO, Sang RC, Konongoi SL, Sow A, De Cock KM, Tukei PM, Okoth FA, Swanepoel R, Burt FJ: Yellow fever outbreak, Imatong, southern Sudan. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004, 10 (6): 1063-1068.

Gould LH, Osman MS, Farnon EC, Griffith KS, Godsey MS, Karch S, Mulenda B, El Kholy A, Grandesso F, de Radigues X: An outbreak of yellow fever with concurrent chikungunya virus transmission in South Kordofan, Sudan, 2005. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene. 2008, 102 (12): 1247-1254. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.014.

Ebola haemorrhagic fever, south Sudan - update. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2004, 79 (25): 229.

Outbreak of Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Yambio, south Sudan, April - June 2004. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2005, 80 (43): 370-375.

Bosch X: Sudan Ebola outbreak of known strain. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2004, 4 (7): 388.

Onyango CO, Opoka ML, Ksiazek TG, Formenty P, Ahmed A, Tukei PM, Sang RC, Ofula VO, Konongoi SL, Coldren RL: Laboratory diagnosis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever during an outbreak in Yambio, Sudan, 2004. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007, 196 (Suppl 2): S193-198.

Abdur Rab M, Freeman TW, Rahim S, Durrani N, Simon-Taha A, Rowland M: High altitude epidemic malaria in Bamian province, central Afghanistan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2003, 9 (3): 232-239.

Cheung E, Mutahar R, Assefa F, Ververs M-T, Nasiri SM, Borrel A, Salama P: An epidemic of scurvy in Afghanistan: assessment and response. Food & Nutrition Bulletin. 2003, 24 (3): 247-255.

Marburg virus disease, Angola. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire/Section d'hygiene du Secretariat de la Societe des Nations = Weekly epidemiological record/Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. 2005, 80 (13): 115-117.

Outbreak of Marburg virus hemorrhagic fever--Angola, October 1, 2004-March 29, 2005. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2005, 54 (12): 308-309.

Bonn D: Marburg fever in Angola: still a mystery disease. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2005, 5 (6).

Enserink M: Crisis of confidence hampers Marburg control in Angola. Science. 2005, 308 (5721): 489-10.1126/science.308.5721.489.

Fisher-Hoch SP: Lessons from nosocomial viral haemorrhagic fever outbreaks. British Medical Bulletin. 2005, 74: 123-137. 10.1093/bmb/ldh054.

Heymann DL, Aylward RB: Poliomyelitis eradication and pandemic influenza. Lancet. 2006, 367 (9521): 1462-1464. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68624-8.

Jeffs B, Roddy P, Weatherill D, de la Rosa O, Dorion C, Iscla M, Grovas I, Palma PP, Villa L, Bernal O: The Medecins Sans Frontieres intervention in the Marburg hemorrhagic fever epidemic, Uige, Angola, 2005. I. Lessons learned in the hospital. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007, 2: S154-161.

Ndayimirije N, Kindhauser MK: Marburg hemorrhagic fever in Angola. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005, 352 (21): 2155-2157. 10.1056/NEJMp058115.

Roddy P, Weatherill D, Jeffs B, Abaakouk Z, Dorion C, Rodriguez-Martinez J, Palma PP, de la Rosa O, Villa L, Grovas I: The Medecins Sans Frontieres intervention in the Marburg hemorrhagic fever epidemic, Uige, Angola, 2005. II. lessons learned in the community. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007, 2: S162-167.

Escriba JM, Nakoune E, Recio C, Massamba PM, Matsika-Claquin MD, Goumba C, Rose AMC, Nicand E, Garcia E, Leklegban C: Hepatitis E, Central African Republic. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2008, 14 (4): 681-683. 10.3201/eid1404.070833.

Grais RF, Dubray C, Gerstl S, Guthmann JP, Djibo A, Nargaye KD, Coker J, Alberti KP, Cochet A, Ihekweazu C: Unacceptably high mortality related to measles epidemics in Niger, Nigeria, and Chad. PLoS Medicine/Public Library of Science. 2007, 4 (1): e16.

Koyange L, Ollivier G, Muyembe JJ, Kebela B, Gouali M, Germani Y: Enterohemorrhagic, Escherichia coli O157, Kinshasa. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004, 10 (5): 968-969.

Influenza outbreak in the district of Bosobolo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, November-December 2002. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2003, 78 (13): 94-96.

Bertherat E, Lamine KM, Rmenty PF, Thuier P, Mondonge V, Mitifu A, Rahalison L: Epidemic of pulmonary plague in a mining camp in the Democratic Republic of Congo: the brutal awakening of an old scourge. Medecine Tropicale. 2005, 65 (6): 511-514.

Joseph JK, Bazile J, Mutter J, Shin S, Ruddle A, Ivers L, Lyon E, Farmer P: Tungiasis in rural Haiti: a community-based response. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006, 100 (10): 970-974. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.11.006.

Chai J-Y, Han E-T, Shin E-H, Park J-H, Chu J-P, Hirota M, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Nawa Y: An outbreak of gnathostomiasis among Korean emigrants in Myanmar. American Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene. 2003, 69 (1): 67-73.

Boumandoki P, Formenty P, Epelboin A, Campbell P, Atsangandoko C, Allarangar Y, Leroy E, Kone L, Molamou A, Dinga-Longa O: Prise en charge des malades et des defunts lors de l'epidemie de fievre hemorragique due au virus Ebola d'octobre a decembre 2003 au Congo. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique. 2005, 98 (3): 208-223.

Visser M: Ebola response in the Republic of Congo. Waterlines. 2005, 23 (3): 22-24. 10.3362/0262-8104.2005.009.

Learned LA, Reynolds MG, Wassa DW, Li Y, Olson VA, Karem K, Stempora LL, Braden ZH, Kline R, Likos A: Extended interhuman transmission of monkeypox in a hospital community in the Republic of the Congo, 2003. American Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene. 2005, 73 (2): 428-434.

Outbreaks of Rift Valley fever in Kenya, Somalia and United Republic of Tanzania, December 2006-April 2007. Releve epidemiologique hebdomadaire/Section d'hygiene du Secretariat de la Societe des Nations = Weekly epidemiological record/Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations. 2007, 82 (20): 169-178.

Depoortere E, Kavle J, Keus K, Zeller H, Murri S, Legros D: Outbreak of West Nile virus causing severe neurological involvement in children, Nuba Mountains, Sudan, 2002. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2004, 9 (6): 730-736. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01253.x.

Cholera outbreak, Zimbabwe. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2009, 84 (7): 50-52.

Chambers K: Zimbabwe's battle against cholera. Lancet. 2009, 373 (9668): 993-994. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60591-2.

Mason PR: Zimbabwe experiences the worst epidemic of cholera in Africa. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2009, 3 (2): 148-151.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the report authors who kindly replied to our emails and provided additional information for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CB designed the search strategy, carried out the review and co-wrote the paper. FC designed the search strategy and co-wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13031_2011_79_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Appendix containing details on the selection of countries included in the review and on the search strategy used. (DOC 167 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bruckner, C., Checchi, F. Detection of infectious disease outbreaks in twenty-two fragile states, 2000-2010: a systematic review. Confl Health 5, 13 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-5-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-5-13