Abstract

Background

Although social skills training programs for people with high-functioning autism (HFA) are widely practiced, the standardization of curricula, the examination of clinical effectiveness, and the evaluation of the feasibility of future trials have yet to be done in Asian countries. To compensate for this problem, a Japanese pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH)-based group social skills training for children with HFA and their mothers was conducted.

Methods

Eleven children with HFA, aged 5–6 years, and their mothers were randomly assigned to the TEACCH program (n=5) or a waiting-list control group (n=6). The program involved comprehensive group intervention and featured weekly 2-hour sessions, totaling 20 sessions over six months. The adaptive behaviors and social reciprocity of the children, parenting stress, and parent–child interactions were assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Parenting Stress Index (PSI), Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II), and Interaction Rating Scale (IRS).

Results

Through this pilot trial, the intervention and evaluation of the program has been shaped. There were no dropouts from the program and the mothers’ satisfaction was high. The outcome measurements improved more in the program group than in the control group, with moderate effect sizes (SDQ, 0.71; PSI, 0.58; BDI-II, 0.40; and IRS, 0.69). This pilot trial also implied that this program is more beneficial for high IQ children and mothers with low stress than for those who are not.

Conclusion

We have standardized the TEACCH program, confirmed the feasibility of a future trial, and successfully estimated the positive effect size. These findings will contribute to a larger trial in the future and to forthcoming systematic reviews with meta-analyses.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Children with high-functioning autism (HFA) are included within the autism spectrum disorders axis and within normal ranges of intelligence and language functioning, but have impaired cognitive functioning, social skills, and adaptive behaviors. One of the core symptoms of HFA is difficulty in developing friendships due to deficits in sharing emotional experiences and understanding others’ perspectives [1]. Behavioral interventions such as social skills training (SST) can improve social skills, enhance social reciprocity, and promote play skills with peers [2, 3]. Previous studies report that many parents of children with HFA experience stress due to their child’s deficits in social communication skills and problem behaviors [4, 5]. It was also shown that the less a child’s developmental progress, the more the parents felt stress. Therefore, parent-mediated intervention and assessment of stress levels is critical in any psychosocial intervention [5].

The National Autism Center’s National Standards Report, based on a comprehensive review [6], recognized the Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication Handicapped Children (TEACCH) program as a major comprehensive psychosocial program. TEACCH was developed to support people of all ages with autism [7] and features the following two aspects: Structured teaching based on the learning styles of children with autism and teaching parents how to assess and implement individualized support for their children. The TEACCH approach also highlights "fun with others" for developing social skills [8], the goal of which is to acquire social skills, and experiencing positive feelings with other people to improve social reciprocity.

A recent Cochrane systematic review on SST in individuals with autism aged 6 to 21 years [9] identified only five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and concluded that more RCTs are needed, especially involving individuals aged 7 years or less in a broader spectrum of cultural settings not restricted to the United States. As for TEACCH, the sole RCT that exists at present targeted only parents with autistic children aged 2–3 years without measuring social communication or child adaptive behaviors [10].

Although SST programs or the TEACCH program for people with HFA are widely practiced in clinical or classroom settings in Japan, neither standardization of the curricula nor examination of the effectiveness has as yet been done [3]. This may be due to difficulties in recruiting a sufficient number of participants, especially preschool children, for a clinical trial and to the underdevelopment of relevant clinical research, including RCT, in Japan. However, it is critically important to perform an appropriately designed RCT beginning with the first patient, both from the scientific and ethical viewpoints [11].

Thus, we conducted this pilot RCT to develop a TEACCH-based group SST program for Japanese children aged five to six years with HFA for the following purposes: To standardize the curricula and outcome measures, to identify the characteristics of persons for whom this program was effective, to evaluate the feasibility of a future trial, and to estimate the effect size of this program.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited by mail and telephone from a group including all children and their families who were assessed at a Japanese medical center that specializes in autism and who were eligible according to the inclusion criteria below. We obtained informed consent from the families who joined the study.

Children aged five to six years (one year before entering elementary school) whose diagnoses were autism spectrum disorders confirmed by child psychiatrists (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10): F84.0), normal intelligence (IQ ≥75), and moderate severity of autism characteristics (CARS-TV ≥25) were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) Children with severe psychiatric comorbidities (e.g., obsessive-compulsive disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder); 2) Mothers with mental illness with a major obstacle in daily life (e.g., schizophrenia, severe depression, or drug or alcohol dependency).

Interventions

TEACCH-based group SST program. The TEACCH approach has been widely practiced in Japan since the 1980s, both in clinical and educational settings. The present program was one that had been done in a specialized autism medical center in Osaka, Japan. The program focused on both children with HFA and their mothers. The program involved comprehensive group intervention in the center and featured weekly 2-hour sessions, totaling 20 sessions over six months. The program providers were two psychologists who were trained in TEACCH methodology and had over five years experience, two nursery teachers, one with one year and the other with 15 years of experience with the TEACCH program, two social workers, and two graduate students studying psychology. A psychologist, who served as advisor for the program for over 20 years, supervised the intervention.

Under the program, children were separated from their mothers. An investigator in this study (KI or HY) observed the program from the next room through a one-way mirror and monitored the program by video. The investigator was not directly involved in the program or outcome evaluation. Each session of the children’s program followed the same format:

-

Warm-up: To monitor the children’s condition (20 min)

-

Description of the rules: To confirm the rules of the program and present the day’s schedule (20 min)

-

Game: To practice playing with other children and to learn to understand the rules and the feelings of other children (10 min)

-

Social Skills Training: See Table 1 (30 min)

-

Exercise: To relax (10 min)

-

Reward and feedback: To provide feedback and strengthen learning (20 min)

-

Feedback to mothers: To understand their children’s characteristics (10 min)

Table 1 shows sample activities in the SST program [2] and outlines the mothers’ program. Each program cost approximately 800 Japanese Yen (about 10 US dollars), along with a payment from health insurance (the total cost for the whole program was approximately 200 US dollars).

Waiting-list control group. Group meetings for mothers were held three times (once every two months) with two social workers for 30–60 minutes per session. The contents of the meetings were not specified or directed by the investigators. After a 6-month non-intervention period, the TEACCH-based SST program was also provided to the control group.

Measures

Baseline demographic characteristics included the children’s profiles and family characteristics: The child’s age, sex, IQ, severity of autism, social competence, disabilities of their siblings, experience in special education programs, mothers’ age, profession, parents’ level of education, use of medical subsidies for infants and children, and educational support for children. DQ was measured by K-test [12], which was equivalent to the IQ of younger PDD children [13]. The severity of autism was measured by the Childhood Autism Rating Scale-Tokyo version (CARS-TV) [[14, 15]. Social competence was measured by the Japanese version of the Social Maturity Scale (SQ: social quotient) [16], which was correlated with those of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) [17].

Primary outcome: SDQ. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [18] measures the adaptive behaviors and social reciprocity of children aged 4–16 years. We used the 25-item version for teachers and parents, which consists of five subscales: Pro-social behavior, conduct problems, hyperactivity, emotional problems, and peer problems [19]. We evaluated the SDQ score provided by the mothers.

Secondary Outcomes: PSI, BDI- II, IRS. The Japanese version of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI) [20, 21] measures parental stress in two major domains: Characteristics of the child and parent. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) is a 21-item depression scale for assessing emotional, behavioral, and somatic symptoms [22, 23]. The Interaction Rating Scale (IRS) [24], which was developed in Japan, is used to measure a child’s social competence and a caregiver’s child rearing competence via five-minute observations of caregiver-child interactions. In this study, we recorded child and parent interactions while they played with a puzzle: Two independent, trained evaluators who were blind to the allocation evaluated child-mother interaction in the videos.

Feasibility of a future trial

We examined the feasibility of a future trial by use of questionnaires that assessed the causes of dropout and mothers’ satisfaction with the contents of the program. We also investigated the mothers’ satisfaction with the length of the session, the duration of intervention, and the frequency and cost of the program, as well as any adverse events or burdens associated with the program.

We also described the baseline characteristics of each child in the intervention group to determine the characteristics of suitable participants for this program.

Study design

Eligible children and their mothers were randomly assigned to an intervention or control group. Children were evaluated both by their mothers and by independent evaluators. The mothers self-reported the condition of their child at baseline and within one month after the end of the intervention (six months after the baseline).

Randomization & sequence generation, allocation concealment

After baseline assessments, an independent allocation manager ran a computer-generated allocation schedule based on the following three variables based on the minimization method of balancing three variables: Sex, autism severity (CARS score ≤30 or CARS score >30), and social competence (SQ score ≤100 or SQ score >100). Program providers were unaware of the allocation sequences.

To avoid bias, we standardized measurements for assessment and employed independent evaluators and independent allocation managers who were blinded to allocation. However, intervention allocation could not be masked from the children and their mothers in the program or from the program providers.

Statistical methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of SDQ, PSI, BDI-II, and IRS, we used intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). We compared the post-intervention scores between the two groups with baseline scores as a covariate. Because of the pilot nature, no hypothesis testing was employed, but 95% confidence intervals (CI) were described for estimated values. Effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated by dividing the baseline SD score of the overall sample by the difference between the intervention and control groups. The sample size required for a future large trial was estimated on the basis of SDQ scores using Stata (version 11.0). Additionally, we analyzed the correlation between the IRS scores of two independent evaluators using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Reporting of the study was complied with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement for non-Pharmacologic Treatment [25, 26]. Analyses were performed using SPSS ver.19 after completion of the assessments.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Kyoto University Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (Registered number: C493). There were no monetary incentives for the participants to join the program. This study was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000004560).

Results

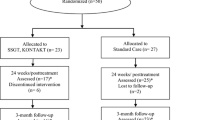

Among 18 families that met the eligibility criteria, five declined to participate given the difficulty of regular participation due to distance (n=2), a subjective burden of the high frequency of the program (n=2), and not feeling the need to participate (n=1). We excluded two families because the children had psychiatric comorbidities: Oppositional defiant disorder. Eleven children were randomly assigned to the program (n=5) or the control group (n=6). Although one family in the program group participated in only 10 sessions due to the mother’s pregnancy, we assessed all participants at the end of the program (see Figure 1).

Demographic features were slightly different between the groups, including age, sex, DQ score, diagnosis, CARS score, SQ score, and background of family education and socio-economic status (see Table 2). Eight families were receiving medical subsidies and five had educational support. Seven families had another child diagnosed with autism.

Attendance in the program was as follows (the control group was assessed after completing the program): Six families completed all 20 sessions, two families completed 19 sessions, one family completed 18 sessions, one family completed 15 sessions, and one family completed 10 sessions (due to the mother’s pregnancy). Regarding program satisfaction, seven families (64%) were satisfied with the overall program, 10 (91%) with the length of each session, nine (82%) with the frequency of the program, eight (73%) with the duration of intervention, and eight (73%) with the cost of the program. Eight families responded that they would recommend this program to others. Nine families responded that they did not have enough time to practice TEACCH in their daily lives. The preferred aspects of the program were "peer counseling (n=11)", "watching the children’s program (n=6)", "parent training (n=6)", and "making manuals for children (n=5)". No adverse events occurred during the program.

The difference in SDQ scores between the intervention and control groups at the endpoint was -3.12 (effect size =0.71). The difference in PSI scores was -18.12 (effect size =0.58) and in BDI-II scores was -2.77 (effect size =0.40). The difference in IRS scores (average of two independent evaluators’ scores) was 2.72 (effect size =0.69). Detailed differences in each participant’s score between baseline and endpoint are shown in Figure 2 and Table 3. From the baseline scores of SDQ and BDI-II, five children were designated as high risk, five were designated as borderline with regard to adaptive behaviors, and nine of the mothers exhibited moderate to severe depressive symptoms.

Change in scores: SDQ, PSI, BDI-II, IRS. Numbers in the figures show each participant’s ID, SDQ: Strengths Difficulties Questionnaire. 0<normal<12, 13<borderline<15, 16<high risk<40, PSI: Parenting Stress Index. Standard score of the Japanese population is 190.8±29.8 (mean±SD). Larger score indicates a more severe condition, ‧BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory II. Standard score of the Japanese population is 8.9±6.5 (mean±SD). Larger score indicates a more severe condition, ‧IRS: Interaction Rating Scale. Smaller score indicates a more severe condition.

The characteristics of child (ID7) whose SDQ score was remarkably improved are as follows: High IQ score (DQ 117), mother with low subjective stress, and no siblings with disabilities. The characteristics of child (ID2) whose SDQ score was moderately improved are a mother with low subjective stress and no siblings with disabilities. The characteristics of child (ID8) whose SDQ score was not improved are as follows: Mother with high stress, siblings with disabilities, and female gender. The characteristics of child (ID9) whose SDQ score was not improved are a low attendance rate at the program, siblings with disabilities, and the mother’s low satisfaction with the program. Concerning child (ID5), the effectiveness of intervention was not clear because this child attended only half of the program due to the mother’s pregnancy.

Correlations between the IRS scores of the independent evaluators were ρ=0.70 for the child IRS score, ρ=0.36 for the parent IRS score, and ρ=0.56 for the total IRS score. The required sample size for a future trial was estimated to be approximately 50, allowing for 10% attrition, with a two-sided p value of 0.05 and an 80% power calculation.

Discussion

This is the first RCT to evaluate the TEACCH-based group social skills training program for Asian children aged five to six years with high-functioning autism and to reveal the feasibility and potential efficacy of this program. Koenig reported that "parents wished for more direct feedback with what was taking place in the group sessions in order to follow up with skill-building at home" [27]. We asked the mothers for direct feedback at the end of each session, and they sometimes watched the programs through one-way mirrors. These considerations may have contributed to the high level of satisfaction with the program. However, the mothers who participated in this program did not use TEACCH skills often in their daily lives. Providing materials, homework, or incentives are potential next steps to put TEACCH skills into daily life.

The effect of the program was quite satisfactory with regard to the children’s adaptive behaviors, social reciprocity, parenting stress, and parent–child interactions. Because the sample size required for a future trial was estimated to be approximately 50 participants, recruitment of participants at multiple facilities similar to the present one is required.

Additionally, the characterization of each child in the intervention group suggested that this program was more effective for the participants whose IQ was high or who had no siblings with disabilities, but was not effective when the mother was heavily stressed. Specialized individual programs may be needed for children with stressed mothers or for lower DQ children. The baseline scores of SDQ and BDI-II revealed that children with HFA had more difficulty in adapting to society and that their mothers were more depressed than their general counterparts. The mothers requested that the program be longer and asked for continuous support after the program. This suggests that we should verify the optimum length of the program in future trials to address this issue.

There are some limitations with this study. First was the lack of blindness because the primary outcome (SDQ) was evaluated by participating mothers. To date, there is no objective measure of children’s social skills in Japan. To compensate for this, we used independent rater outcome (IRS) to assess secondary outcomes. High agreement between measurements by two independent evaluators indicated little possibility of serious bias in the present evaluation. The second was limited sample size. The present trial was a pilot of which the primary purpose was not to test a hypothesis but to standardize the program, examine its feasibility, and to estimate potential effect size. Because randomization was strictly conducted and reported in accordance with the CONSORT statement, the present trial was successful and will lead to a relevant larger trial and forthcoming systematic reviews with meta-analyses.

Conclusion

This pilot study confirmed the feasibility and potential efficacy of TEACCH-based social skills training in Asia. High-functioning children with autism were able to develop social skills and reciprocity, and their mothers’ stress was reduced. This trial also implied that this program may be especially effective for high IQ children and mothers with low stress. It will contribute to a larger trial in the future and to forthcoming systematic reviews with meta-analyses.

References

Carpenter LA, Soorya L, Halpern D: Asperger’s Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism. Pediatr Annu. 2009, 38: 30-35. 10.3928/00904481-20090101-01.

Koenig K, De Los Reyes A, Cicchetti D, Scahill L, Klin A: Group intervention to promote social skills in school-age children with pervasive developmental disorders: reconsidering efficacy. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009, 39: 1163-1172. 10.1007/s10803-009-0728-1.

Rao PA, Beidel DC, Murray MJ: Social skills interventions for children with Asperger’s syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review and recommendations. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008, 38: 353-361. 10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4.

Mori K, Ujiie T, Smith A, Howlin P: Parental stress associated with caring for children with Asperger’s syndrome or autism. Pediatr Int. 2009, 51: 364-370. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02728.x.

Rao PA, Beidel DC: The impact of children with high-functioning autism on parental stress, sibling adjustment, and family functioning. Behav Modif. 2009, 33: 437-451. 10.1177/0145445509336427.

Wilczynski SM: National Standards Report. 2009, [http://www.nationalautismcenter.org/pdf/NAC%20Standards%20Report.pdf#search=’National%20standard%20report’] Accessed 19 November 2012

Schopler E, Brehm SS, Kinsbour M, Reichler RJ: Effect of Treatment Structure on Development in Autistic Children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971, 24: 415-421. 10.1001/archpsyc.1971.01750110027005.

Mesibov GBSV, Shopler E: The TEACCH Approach To Autism Spectrum Disorders (Issues in Clinical Child Psychology). 2004, USA: Plenum Publish Corporation

Reichow B, Steiner AM, Volkmar F: Social skills groups for people aged 6 to 21 with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, 7: CD008511

Mesibov GB, Shea V: The TEACCH Program in the Era of Evidence-Based Practice. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010, 40: 570-579. 10.1007/s10803-009-0901-6.

Spodick DH: Randomized Controlled Clinical-Trials - The Behavioral Case. Jama. 1982, 247: 2258-2260. 10.1001/jama.1982.03320410040028.

Shinpan K shiki Hattatsu Kensahou 2001 Nenban [the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development test 2001. Edited by: Society for Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development Test. 2008, Japan: Nakanishiya Shuppan, in Japansese

Koyama T, Osada H, Tsujii H, Kurita H: Utility of the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development in cognitive assessment of children with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009, 63: 241-243. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01931.x.

Schopler E, Reichler RJ, Devellis RF, Daly K: Toward Objective Classification of Childhood Autism - Childhood Autism Rating-Scale (CARS). J Autism Dev Disord. 1980, 10: 91-103. 10.1007/BF02408436.

Kurita H, Miyake Y, Katsuno K: Reliability And Validity of The Childhood Autism Rating-Scale-Tokyo Version (CARS-TV). J Autism Dev Disord. 1989, 19: 389-396. 10.1007/BF02212937.

Miki Y: Social Maturity Scale. 1980, Japan: Nihon Bunka Kagakusha

Roszkowski MJ: Concurrent Validity of The Adaptive-Behavior Scale as Assessed by The Vineland Social Maturity Scale. Am J Ment Defic. 1980, 85: 86-89.

Goodman R: The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1997, 38: 581-586. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x.

Matsuishi T, Nagano M, Araki Y, et al: Scale properties of the Japanese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): A study of infant and school children in community samples. Brain Dev. 2008, 30: 410-415. 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.003.

Narama M, Kanematsu Y, Arai A, et al: Validity and Reliability of the Japanese Version of the Parenting Stress lndex. The Journal of Child Health. 1999, 58: 610-616.

Abidin RR: Parenting stress index: professional manual. 1995, Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources

Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG: Psychometric Properties of The Beck Depression Inventory - 25 Years of Evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988, 8: 77-100. 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5.

Kojima M, Furukawa TA, Takahashi H, Kawai M, Nagaya T, Tokudome S: Cross-cultural validation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 2002, 110: 291-299. 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00106-3.

Anme T, Shinohara R, Sugisawa Y, et al: Interaction Rating Scale (IRS) as an Evidence-Based Practical Index of Children’s Social Skills and Parenting. J Epidemiol. 2010, 20 (Suppl 2): S419-S426.

Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P: Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148: 295-309. 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008.

Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al: Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. Jama. 1996, 276: 637-639. 10.1001/jama.1996.03540080059030.

Koenig K, White SW, Pachler M, et al: Promoting Social Skill Development in Children With Pervasive Developmental Disorders: A Feasibility and Efficacy Study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010, 40: 1209-1218. 10.1007/s10803-010-0979-x.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all of the families and children who participated in the study and the staff of the Osaka Psychiatric Medical Center (Takao Kagomoto, Mariko Shibata, and Kazuhiko Iwata). Support for the trial design was provided by the staff of the Master of Clinical Research (MCR) course of Kyoto University. We especially thank those who provided the program (Junko Satake, Miki Hirai, Kuniko Doihara, Yuko Kawauchi, Yuka Katoh, Sayuri Nakatani and Tadahiro Kanazawa); we could not have accomplished this study without their cooperation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

This study was funded by a grant from the Meiji Yasuda Mental Health Foundation in 2011. The foundation had no role in data collection, analysis or interpretation of the study. We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions

KI conceived this study and performed the study design and the statistical analysis. YT and TI and TN participated in the design of this study and helped to draft the manuscript. MA made the computer based random allocation system. TA developed the Interaction Rating Scale (IRS) and trained the independent evaluators. HY coordinated and observed the intervention to check the feasibility of intervention. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ichikawa, K., Takahashi, Y., Ando, M. et al. TEACCH-based group social skills training for children with high-functioning autism: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BioPsychoSocial Med 7, 14 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0759-7-14

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0759-7-14