Abstract

Chinese medicine has been used to treat a variety of cancer-related conditions. This study aims to examine the prevalence and patterns of Chinese medicine usage by cancer patients. We reviewed articles written in English and found only the Chinese medicine usage from the studies on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Seventy four (74) out of 81 articles reported rates of CAM usage ranging from 2.6 to 100%. Acupuncture was reported in 71 out of 81 studies. Other less commonly reported modalities included Qigong (n = 17), Chinese herbal medicine (n = 11), Taichi (n = 10), acupressure (n = 6), moxibustion (n = 2), Chinese dietary therapy (n = 1), Chinese massage (n = 1), cupping (n = 1) and other Chinese medicine modalities (n = 19). This review also found important limitations of the English language articles on CAM usage in cancer patients. Our results show that Chinese medicine, in particular Chinese herbal medicine, is commonly used by cancer patients. Further research is warranted to include studies not written in English.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Conventional cancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy have shown some effectiveness for reducing or eradicating cancers; however, they can produce unpleasant side effects, e.g. nausea, vomiting, changes in bowel habits, fatigue and hair loss. Chinese medicine is increasingly used as an adjunctive treatment option for cancer patients and a way of reducing or managing side effects of conventional cancer treatment.

Chinese medicinal herbs such as Ginkgo biloba has been reported to have chemo-preventive activities for treating certain cancers such as ovarian, breast and brain [1]. Acupuncture is being used to relieve side effects of conventional cancer treatment. While some laboratory and clinical research found some immune boosting capabilities of acupuncture in cancer patients [2, 3], most clinical research has focused on symptom management, in particular, the management of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting [4–6].

This study reviews the articles published in English language complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) literature on the prevalence and patterns of Chinese medicine usage by cancer patients and informs patients, researchers, health care providers and policy makers of the current use of Chinese medicine in the CAM context.

Methods

Literature search

Our working definition of CAM was an inclusive term incorporating both complementary medicine and therapies (modalities and/or systems), namely the concepts of health and medical systems, practices and products not currently recognised as part of conventional medicine, alternative medicine, traditional medicine (indigenous medicine and practices), and integrative medicine (CAM used alongside with the mainstream medicine) [7]. For the purposes of this review Chinese medicine includes acupuncture, Chinese herbal medicine, remedial massage, exercise and breathing therapy (e.g. Qigong) as well as diet and lifestyle advice in primary health care [8].

We searched major databases, namely AMED, CINAHL, PubMED, Science Direct and Cochrane Library, using specific terms to retrieve surveys published in English. One author (BC) screened all the titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies. Survey studies containing prevalence rates for at least one Chinese medicine modality for treating cancer patients were included. Studies on children were not excluded.

Data extraction

The following data was extracted: country of study, number of study participants, type of study (quantitative, qualitative, mixed), group setting (e.g. hospital, cancer registry), type of cancer, age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, prevalence of individual Chinese medicine modality, prevalence, sources of CAM information and reasons for CAM usage.

Quality-assessment

The quality of the CAM surveys were assessed according to Bishop et al.[9], based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [10]. Reported information was assessed with scores which were weighted for importance. Both authors (BC and CAS) scored the included articles. Final scores were consensus of both authors. Four articles [11–14] were primarily qualitative and therefore not assessed. Three items were scored a maximum of two points, eight items one point and six items 0.5 points. The maximum total score was 17.

Data analysis

We described the general characteristics of users of Chinese medicine including both Chinese medicine specific studies and Chinese medicine embedded within CAM studies. Data was analysed with SPSS Statistics 17.0 (IBM, USA). Descriptive statistics, means, medians, ranges, frequencies and percentages characterised the studies.

Results

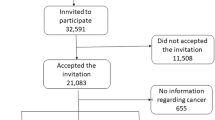

The search identified a total of 411 studies for screening. Ninety nine screened articles were retrieved for further evaluation. Eighty one studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the studies

The included 81 studies spanned a period of 15 years (Table 1), with the majority published in the last five years (60.5%). While the surveys were carried out around the world, a large number of surveys were conducted in North America, the United States (US) in particular (33.3%). Sample sizes of the studies ranged from 16 to 22,352 with a median of 189 participants. Two thirds of the participants were female (66.7%). Participants had a mean age of 56.0 ± 11.9 years (mean ± standard deviation, SD) (ranging from 3 to 71 years), were married or in a de facto marriage (70.6%) and had completed high school education (35.8%). The majority (84.5%) were of Caucasian ethnicity. Survey participants were recruited from hospital settings including outpatient clinics, cancer institutes and palliative care (70.4%), with convenience sampling (61%). Participants had a range of cancers (49.4%); however, a significant focus was on women with breast cancer (25.9%). Most studies used a self-administered questionnaire (52%).

Prevalence of Chinese medicine use

Seventy four studies reported the rates of CAM usage which ranged from 2.6 to 100%. Acupuncture was the most frequently reported Chinese medicine modality included within CAM. A total of 71 studies reported data on acupuncture. Other less commonly reported modalities included Qigong, Chinese herbal medicine, Taichi, acupressure, moxibustion, Chinese dietary therapy, Chinese massage and cupping.

We examined the prevalence of Chinese medicine usage and reported the range and a mean prevalence (Table 2). Chinese herbal medicine was the most frequently used modality within Chinese medicine; however data were only available from 11 of the 81 studies. Usage ranged from a low prevalence of 0.7% to a high prevalence of 94.4%, with an average use rate of 35.6%. Acupuncture prevalence ranged from 0.2 to 17.1% with a mean of 4.5% extracted from 71 studies. Usage of Qigong by cancer patients was reported in 17 studies with a mean prevalence rate of 12.7%. Usage reported in these studies ranged from 0.4 to 100%. Taichi prevalence ranged from 1.7 to 40.6% reported in ten studies with a mean of 9.0%. Other Chinese medicine modalities (acupressure, Chinese dietary therapies, Chinese massage, moxibustion and cupping) were reported with few data in the 11 studies covering these modalities (Table 2). Mixed Chinese medicine prevalence rates (where cancer patients reported using several Chinese modalities concurrently) were also reported. Nineteen of the studies reported such data with a mean prevalence of 17.8% (ranging from 0.3 to 100%).

Use patterns of Chinese medicine modalities

Our search identified nine studies that provided detailed data on the usage patterns of Chinese medicine [11, 15–22]. The aims of these studies were quite diverse. We were not able to provide a systematic summary of these data but a narrative summary.

Studies examining patterns of Chinese medicine usage varied in study design. One study used qualitative methods [11]; another study used a retrospective analysis of insurance registration and claim datasets [20], and seven studies were questionnaire-based surveys [15–19, 21, 22]. All seven surveys included Chinese or other Asian populations (Mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore), or Chinese immigrants in Canada. Seven studies reported an overall Chinese medicine usage rate attributed to Chinese medicinal herbs, Qigong, acupuncture and moxibustion.

Within the nine studies, usage of Chinese medicinal herbs varied widely; however the majority reported high usage of 94.4% [19], 93.75% [11], 86.4% [17], 76.75% [15] and one low rate of 2.48% [20]. Examples are presented in the following studies. Shih et al.[22] reported additional details on the types of Chinese medicinal herbs and related modalities in particular food supplements. Forty five percent of participants used bird (swallow) nests and 28.6% chicken essence; 53% used prescribed herbs, of which 15.4% used Lingzhi, and 8% used Chinese herbal formulae. In the study by Xu et al.[11], 50% of participants used individually tailored herbs, 6% standard herbal formulae and 38% both types. Xu et al. reported that all participants (n = 16) practiced Qigong.

Characteristics of Chinese medicine users

Three [17, 18, 21] of the nine studies reported the characteristics of Chinese medicine users. Pu et al.[21] surveyed 2034 patients with cervical, breast, lung, liver and colorectal cancers and highlighted patients' usage of Chinese medicine modalities according to cancer types. Chinese medicine as a broad modality was more likely to be used by patients with breast, lung, liver and colorectal cancers whereas acupuncture was more likely to be used by liver and colorectal patients. Pu et al. examined the correlation of socio-economic factors (e.g. religion, education and income) with Chinese medicine usage. While more Buddhists used Chinese medicine, acupuncture usage was not distinctive in patients with any religion. Acupuncture users were mostly female cancer patients with higher education. According to the study by Pu et al., participants earning a higher income were about 52% more likely than lower income groups to use Chinese medicine. Similarly, Cui et al.[17] found that more participants with a higher education and higher income used Chinese herbal medicine. Ferro et al.[18] found that Chinese medicine was used by less acculturated patients twice as much as acculturated patients.

Motivation to use and the perceived effectiveness of Chinese medicine

Motivation to use and the perceived effectiveness of Chinese medicine modalities were reported in three studies [11, 15, 17]. Xu et al.[11] highlighted four important reasons for Chinese medicine usage among 28 Chinese cancer patients: (1) Chinese medicine as a popular and culturally acceptable process of self-help, (2) fear of chemotherapy damaging the vital essence, (3) importance of individualised prescriptions and (4) empowerment with self-help. Almost all participants used Chinese medicine to avoid or reduce adverse effects from cancer treatment. Overall, health benefits, quality of life and ability to function were significantly improved with Chinese medicine. Benefits attributed to Chinese medicine included reduced fatigue, nausea and vomiting, constipation, stress, weakness and weight gain.

Cui et al.[17] found that the most common reason for using Chinese herbal medicine among breast cancer patients was cancer treatment (81.5%), followed by immune system enhancement (12%), metastasis prevention or side effect management (7.9%), and the reduction of menopausal symptoms (4.7%). Chinese herbal medicine was perceived to be effective or very effective for cancer treatment (78.7%), and 77% of female patients perceived Chinese medicine to be very effective or effective for immune system enhancement. Similar levels of effectiveness were reported for metastasis management and the reduction of menopausal symptoms. Acupuncture, on the other hand, was reported to be less effective with only 48.1% of users considering it to be effective. Chen et al.[15] found far more sceptical views among breast cancer patients with only 52% of patients perceiving Chinese herbal medicine as effective and 4% as very effective in assisting cancer treatment.

Study quality

Overal study quality (Additional file 1) was scored between 32 and 94%, with 95% of studies scoring above a 50% threshold for the 77 quantitiave studies [15–91]. Fourty four studies omitted piloting of instruments. Fourty seven studies used convenience sampling. Only eight studies reported non-response bias. Overall measures of socio-economic status were included and reported. All studies reported prevalence but many failed to examine the reasons for usage. Many cancer studies (n = 11) reported the usage starting from the time of diagnosis, thereby omitting patterns of usage prior to diagnosis.

Discussion

Acupuncture was the most frequently reported Chinese medicine modality with nearly 90% of the studies containing prevalence data. However, among more comprehensive studies of Chinese medicine modalities, Chinese herbal medicine was the most commonly used form of Chinese medicine.

Increasing prevalence of CAM usage by cancer patients reflects the growing use of CAM over time [92]. Our review suggests a higher CAM prevalence compared with a prevalence of 31.4%, and a range of 7-64%, reported by Ernst [93]. However, unlike Ernst, we were unable to access non-English language publications.

Major limitations of the studies on the use of Chinese medicine in relation to cancer are as follows. Firstly, non-English language studies, in particular those written in Chinese, were not reviewed and should be included in future studies. Moreover, the inability to access the EMBASE database might have excluded some English language reports. Secondly, the variation in the wide range of CAM use is likely explainable by different cultural contexts, understandings and definitions of what constitutes CAM. Thirdly, incomplete reporting of the definition of CAM adopted by many studies, and the lack of rationale for selecting Chinese medicine modalities were not uncommon. Furthermore, extensive demographic characteristics and related details were not reported. Sampling of the participant population and the generalisability of the findings was not justified. Fourthly, qualitative research accompanied by cross sectional and longitudinal surveys and additional information about cultural and ethnic populations was insufficient for cross cultural comparisons. Further studies should address these limitations.

Conclusion

Our results show that Chinese medicine, in particular Chinese herbal medicine, is commonly used by cancer patients. Further research is warranted to include studies not written in English.

Abbreviations

- CAM:

-

complementary and alternative medicine

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- US:

-

United States

- SD:

-

standard deviation

References

Amin A, Kucuk O, Khuri FR, Shin DM: Perspectives for cancer prevention with natural compounds. J Clinical Oncol. 2009, 27: 2712-10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6235.

Liu LJ, Guo CJ, Jiao XM: Effect of acupuncture on immunologic function and histopathology of transplanted mammary cancer in mice. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1995, 15 (10): 615-7.

Wu B, Zhou R, Zhou M: Effect of acupuncture on interleukin-2 level and NK cell immunoactivity of peripheral blood of malignant tumor patients. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1994, 14: 537-9.

Dundee J, Ghaly R, Fitzpatrick K, Abram W, Lynch G: Acupuncture prophylaxis of cancer chemotherapy-induced sickness. J R Soc Med. 1989, 82: 268-71.

Shen J, Wenger N, Glaspy J, Hays R, Albert P, Choi C, Shekelle P: Electroacupuncture for control of myeloablative chemotherapy-induced emesis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000, 284: 2755-61. 10.1001/jama.284.21.2755.

Aglietti L, Roila F, Tonato M, Basurto C, Bracarda S, Picciafuoco M, Ballatori E, Del Favero A: A pilot study of metoclopramide, dexamethasone, diphenhydramine and acupuncture in women treated with cisplatin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1990, 26: 239-240. 10.1007/BF02897209.

About Complementary Medicine: Definition of complementary medicine. [http://www.nicm.edu.au/content/view/31/35/]

Health Services: Acupuncture. [http://www.acupuncture.org.au/acupuncture.cfm]

Bishop FL, Prescott P, Chan YK, Saville J, von Elm E, Lewith GT: Prevalence of complementary medicine use in pediatric cancer: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010, 125: 768-776. 10.1542/peds.2009-1775.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007, 85: 867-872.

Xu W, Towers A, Li P, Collet J: Traditional Chinese medicine in cancer care: perspectives and experiences of patients and professionals in China. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2006, 15: 397-403. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00685.x.

Canales MK, Geller BM: Surviving breast cancer: the role of complementary therapies. Fam Community Health. 2003, 26: 11-24.

Hök J, Tishelman C, Ploner A, Forss A, Falkenberg T: Mapping patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer: An explorative cross-sectional study of individuals with reported positive" exceptional" experiences. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008, 8: 48-10.1186/1472-6882-8-48.

Singh H, Maskarinec G, Shumay DM: Understanding the motivation for conventional and complementary/alternative medicine use among men with prostate cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005, 4: 187-194. 10.1177/1534735405276358.

Chen Z, Gu K, Zheng Y, Zheng W, Lu W, Shu XO: The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Chinese women with breast cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2008, 14: 1049-1055. 10.1089/acm.2008.0039.

Chow WH, Chang P, Lee SC, Wong A, Shen HM, Verkooijen HM: Complementary and alternative medicine among Singapore cancer patients. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010, 39: 129-135.

Cui Y, Shu XO, Gao Y, Wen W, Ruan ZX, Jin F, Zheng W: Use of complementary and alternative medicine by Chinese women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004, 85: 263-270. 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025422.26148.8d.

Ferro M, Leis A, Doll R, Chiu L, Chung M, Barroetavena M: The impact of acculturation on the use of traditional Chinese medicine in newly diagnosed Chinese cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2007, 15: 985-992. 10.1007/s00520-007-0285-0.

Lam YC, Cheng CW, Peng H, Law CK, Huang X, Bian Z: Cancer patients' attitudes towards Chinese medicine: a Hong Kong survey. Chin Med. 2009, 4: 25-10.1186/1749-8546-4-25.

Lin Y, Chen K, Chiu J: Prevalence, patterns, and costs of Chinese medicine use among prostate cancer patients: A population-based study in Taiwan. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010, 9: 16-23. 10.1177/1534735409359073.

Pu C, Lan V, Lan C, Lang H: The determinants of traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture utilization for cancer patients with simultaneous conventional treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2008, 17: 340-349. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00865.x.

Shih V, Chiang J, Chan A: Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) usage in Singaporean adult cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2009, 20: 752-7. 10.1093/annonc/mdn659.

Can G, Erol O, Aydiner A, Topuz E: Quality of life and complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer patients in Turkey. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009, 13: 287-94. 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.03.007.

Hamidah A, Rustam ZA, Tamil AM, Zarina LA, Zulkifli ZS, Jamal R: Prevalence and parental perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine use by children with cancer in a multi ethnic Southeast Asian population. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009, 52: 70-74. 10.1002/pbc.21798.

Johannessen H, von Bornemann Hjelmborg J, Pasquarelli E, Fiorentini G, Di Costanzos F, Miccinesi G: Prevalence in the use of complementary medicine among cancer patients in Tuscany, Italy. Tumori. 2008, 94: 406-10.

McKay DJ, Bentley JR, Grimshaw RN: Complementary and alternative medicine in gynaecologic oncology. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005, 27: 562-568.

Molassiotis A, Browall M, Milovics L, Panteli V, Patiraki E, Fernandez OP: Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with gynecological cancers in Europe. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006, 16 (Suppl 1): 219-224.

Shakeel M, Newton J, Bruce J, Ah-See K: Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients attending a head and neck oncology clinic. J Laryngol Otol. 2008, 122: 1360-1364. 10.1017/S0022215108001904.

Wilkinson S, Farrelly S, Low J, Chakraborty A, Williams R: The use of complementary therapy by men with prostate cancer in the UK. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2008, 17: 492-499. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00904.x.

Yang C, Chien LY, Tai CJ: Use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with cancer receiving outpatient chemotherapy in Taiwan. J Altern Complement Med. 2008, 14: 413-416. 10.1089/acm.2007.7181.

Akyuz A, Dede M, Cetinturk A, Yavan T, Yenen MC, Sarici SU, Dilek S: Self-application of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007, 64: 75-81. 10.1159/000099634.

Goldstein MS, Lee JH, Ballard Barbash R, Brown ER: The use and perceived benefit of complementary and alternative medicine among Californians with cancer. Psychooncology. 2008, 17: 19-25. 10.1002/pon.1193.

Helyer LK, Chin S, Chui BK, Fitzgerald B, Verma S, Rakovitch E, Dranitsaris G, Clemons M: The use of complementary and alternative medicines among patients with locally advanced breast cancer - a descriptive study. BMC cancer. 2006, 6: 39-10.1186/1471-2407-6-39.

Lawsin C, DuHamel K, Itzkowitz SH, Brown K, Lim H, Thelemaque L, Jandorf L: Demographic, medical, and psychosocial correlates to CAM use among survivors of colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007, 15: 557-564. 10.1007/s00520-006-0198-3.

Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Xie SX, Bowman MA, Armstrong K: Use of complementary and alternative medicine and prayer among a national sample of cancer survivors compared to other populations without cancer. Complement Ther Med. 2007, 15: 21-29. 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.07.006.

Mertens AC, Sencer S, Myers CD, Recklitis C, Kadan Lottick N, Whitton J, Marina N, Robison LL, Zeltzer L: Complementary and alternative therapy use in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008, 50: 90-97. 10.1002/pbc.21177.

Molassiotis A, Scott JA, Kearney N, Pud D, Magri M, Selvekerova S, Bruyns I, Fernadez-Ortega P, Panteli V, Margulies A: Complementary and alternative medicine use in breast cancer patients in Europe. Support Care Cancer. 2006, 14: 260-267. 10.1007/s00520-005-0883-7.

Montazeri A, Sajadian A, Ebrahimi M, Haghighat S, Harirchi I: Factors predicting the use of complementary and alternative therapies among cancer patients in Iran. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007, 16: 144-149. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00722.x.

Mueller CM, Mai PL, Bucher J, Peters JA, Loud JT, Greene MH: Complementary and alternative medicine use among women at increased genetic risk of breast and ovarian cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008, 8: 17-10.1186/1472-6882-8-17.

Wells M, Sarna L, Cooley ME, Brown JK, Chernecky C, Williams RD, Padilla G, Danao LL: Use of complementary and alternative medicine therapies to control symptoms in women living with lung cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2007, 30: 45-55. 10.1097/00002820-200701000-00008.

Fox S, Laws ER, Anderson F, Farace E: Complementary therapy use and quality of life in persons with high-grade gliomas. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006, 38: 212-220. 10.1097/01376517-200608000-00003.

Gray RE, Fitch M, Goel V, Franssen E, Labrecque M: Utilization of complementary/alternative services by women with breast cancer. J Health Soc Policy. 2003, 16: 75-84.

Habermann TM, Thompson CA, LaPlant BR, Bauer BA, Janney CA, Clark MM, Rummans TA, Maurer MJ, Sloan JA, Geyer SM: Complementary and alternative medicine use among long term lymphoma survivors: A pilot study. Am J Hematol. 2009, 84: 795-798. 10.1002/ajh.21554.

Harris P, Finlay IG, Cook A, Thomas KJ, Hood K: Complementary and alternative medicine use by patients with cancer in Wales: a cross sectional survey* 1. Complement Ther Med. 2003, 11: 249-253. 10.1016/S0965-2299(03)00126-2.

Hyodo I, Amano N, Eguchi K, Narabayashi M, Imanishi J, Hirai M, Nakano T, Takashima S: Nationwide survey on complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 2645-2654.

Kim MJ, Kim DR, Sohn WS, Kim J, Han CJ, Nam HS, Kim CH: Use of complementary and alternative medicine among Korean cancer patients. Korean J Intern Med. 2004, 19: 250-256.

Lewith G, Broomfield J, Prescott P: Complementary cancer care in Southampton: a survey of staff and patients. Complement Ther Med. 2002, 10: 100-106. 10.1054/ctim.2002.0525.

Molassiotis A, Fernadez-Ortega P, Pud D, Ozden G, Scott JA, Panteli V, Margulies A, Browall M, Magri M, Selvekerova S: Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005, 16: 655-663. 10.1093/annonc/mdi110.

Molassiotis A, Fernandez-Ortega P, Pud D, Ozden G, Platin N, Hummerston S, Scott JA, Panteli V, Gudmundsdottir G, Selvekerova S: Complementary and alternative medicine use in colorectal cancer patients in seven European countries. Complement Ther Med. 2005, 13: 251-257. 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.07.002.

Molassiotis A, Margulies A, Fernandez-Ortega P, Pud D, Panteli V, Bruyns I, Scott JA, Gudmundsdottir G, Browall M, Madsen E: Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with haematological malignancies in Europe. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2005, 11: 105-110. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2004.12.005.

Molassiotis A, Ozden G, Platin N, Scott JA, Pud D, Fernandez OP, Milovics L, Panteli V, Gudmundsdottir G, Browall M: Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients with head and neck cancers in Europe. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2006, 15: 19-24. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00615.x.

Molassiotis A, Panteli V, Patiraki E, Ozden G, Platin N, Madsen E, Browall M, Fernandez-Ortega P, Pud D, Margulies A: Complementary and alternative medicine use in lung cancer patients in eight European countries. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2006, 12: 34-39. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2005.09.007.

Schieman C, Rudmik LR, Dixon E, Sutherland F, Bathe OF: Complementary and alternative medicine use among general surgery, hepatobiliary surgery and surgical oncology patients. Can J Surg. 2009, 52: 422-426.

Scott JA, Kearney N, Hummerston S, Molassiotis A: Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with cancer: a UK survey. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005, 9: 131-137. 10.1016/j.ejon.2005.03.012.

Talmi YP, Yakirevitch A, Migirov L, Horowitz Z, Bedrin L, Simon Z, Pfeffer MR: Limited use of complementary and alternative medicine in Israeli head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope. 2005, 115: 1505-1508. 10.1097/01.mlg.0000172205.31559.8d.

Tam K, Cheng DKL, Ng T, Ngan HYS: The behaviors of seeking a second opinion from other health-care professionals and the utilization of complementary and alternative medicine in gynecologic cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2005, 13: 679-684. 10.1007/s00520-005-0841-4.

van der Weg F, Streuli RA: Use of alternative medicine by patients with cancer in a rural area of Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003, 133: 233-240.

Yap KPL, McCready DR, Fyles A, Manchul L, Trudeau M, Narod S: Use of alternative therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen after surgery. Breast J. 2004, 10: 481-486. 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2004.21497.x.

Yates JS, Mustian KM, Morrow GR, Gillies LJ, Padmanaban D, Atkins JN, Issell B, Kirshner JJ, Colman LK: Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients during treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2005, 13: 806-811. 10.1007/s00520-004-0770-7.

Ashikaga T, Bosompra K, O'Brien P, Nelson L: Use of complimentary and alternative medicine by breast cancer patients: prevalence, patterns and communication with physicians. Support Care Cancer. 2002, 10: 542-548. 10.1007/s00520-002-0356-1.

Begbie SD, Kerestes ZL, Bell DR: Patterns of alternative medicine use by cancer patients. Med J Aust. 1996, 165: 545-547.

Boon HS, Olatunde F, Zick SM: Trends in complementary/alternative medicine use by breast cancer survivors: comparing survey data from 1998 and 2005. BMC Womens Health. 2007, 7: 4-10.1186/1472-6874-7-4.

Burstein HJ, Gelber S, Guadagnoli E, Weeks JC: Use of alternative medicine by women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999, 340: 1733-1739. 10.1056/NEJM199906033402206.

Chrystal K, Allan S, Forgeson G, Isaacs R: The use of complementary/alternative medicine by cancer patients in a New Zealand regional cancer treatment centre. N Z Med J. 2003, 116: 1168-

Corner J, Yardley J, Maher E, Roffe L, Young T, Maslin-Prothero S, Gwilliam C, Haviland J, Lewith G: Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use among patients undergoing cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2009, 18: 271-279. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00911.x.

DiGianni LM, Kim HT, Emmons K, Gelman R, Kalkbrenner KJ, Garber JE: Complementary medicine use among women enrolled in a genetic testing program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003, 12: 321-326.

Hann D, Baker F, Denniston M, Entrekin N: Long-term breast cancer survivors' use of complementary therapies: perceived impact on recovery and prevention of recurrence. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005, 4: 14-20. 10.1177/1534735404273723.

Hann D, Baker F, Roberts C, Witt C, McDonald J, Livingston M, Ruiterman J, Ampela R, Crammer C, Kaw O: Use of complementary therapies among breast and prostate cancer patients during treatment: a multisite study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005, 4: 294-300. 10.1177/1534735405282109.

Henderson J, Donatelle R: Complementary and alternative medicine use by women after completion of allopathic treatment for breast cancer. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004, 10: 52-57.

Heusser P, Braun S, Ziegler R, Bertschy M, Helwig S, van Wegberg B, Cerny T: Palliative in-patientcancer treatment in an anthroposophic hospital: I. Treatment patterns and compliance with anthroposophic Medicine*. Forsch Komplementmed. 2006, 13: 94-100. 10.1159/000091694.

Kremser T, Evans A, Moore A, Luxford K, Begbie S, Bensoussan A, Marigliani R, Zorbas H: Use of complementary therapies by Australian women with breast cancer. Breast. 2008, 17: 387-394. 10.1016/j.breast.2007.12.006.

Lafferty WE, Bellas A, Corage Baden A, Tyree PT, Standish LJ, Patterson R: The use of complementary and alternative medical providers by insured cancer patients in Washington state. Cancer. 2004, 100: 1522-1530. 10.1002/cncr.20105.

Lee MM, Chang JS, Jacobs B, Wrensch MR: Complementary and alternative medicine use among men with prostate cancer in 4 ethnic populations. Am J Public Health. 2002, 92: 1606-1609. 10.2105/AJPH.92.10.1606.

Lengacher CA, Bennett MP, Kip KE, Keller R, LaVance MS, Smith LS, Cox CE: Frequency of use of complementary and alternative medicine in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002, 29: 1445-1452. 10.1188/02.ONF.1445-1452.

Li-chun C: Patterns of complementary therapy use by homebound cancer patients in Taiwan. Appl Nurs Res. 2004, 17: 41-47. 10.1016/j.apnr.2003.10.006.

Oneschuk D, Hanson J, Bruera E: Complementary therapy use: a survey of community-and hospital-based patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2000, 14: 432-434. 10.1191/026921600701536129.

Pud D, Kaner E, Morag A, Ben-Ami S, Yaffe A: Use of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients in Israel. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005, 9: 124-130. 10.1016/j.ejon.2005.03.011.

Rees R, Feigel I, Vickers A, Zollman C, McGurk R, Smith C: Prevalence of complementary therapy use by women with breast cancer: a population-based survey. Eur J Cancer. 2000, 36: 1359-1364. 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00099-X.

Shen J, Andersen R, Albert PS, Wenger N, Glaspy J, Cole M, Shekelle P: Use of complementary/alternative therapies by women with advanced-stage breast cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002, 2: 8-10.1186/1472-6882-2-8.

Shumay DM, Maskarinec G, Gotay CC, Heiby EM, Kakai H: Determinants of the degree of complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with cancer. J Altern Complement Med. 2002, 8: 661-671. 10.1089/107555302320825183.

Sparber A, Bauer L, Curt G, Eisenberg D, Levin T, Parks S, Steinberg S, Wootton J: Use of complementary medicine by adult patients participating in cancer clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000, 27: 623-630.

Tovey P, Broom A, Chatwin J, Ahmad S, Hafeez M: Use of traditional, complementary and allopathic medicines in Pakistan by cancer patients. Rural Remote Health. 2005, 5: 447-

VandeCreek L, Rogers E, Lester J: Use of alternative therapies among breast cancer outpatients compared with the general population. Altern Ther Health Med. 1999, 5: 71-76.

Vapiwala N, Mick R, Hampshire MK, Metz JM, DeNittis AS: Patient initiation of complementary and alternative medical therapies (CAM) following cancer diagnosis. Cancer J. 2006, 12: 467-474. 10.1097/00130404-200611000-00006.

Yoshimura K, Ichioka K, Terada N, Terai A, Arai Y: Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with localized prostate carcinoma: study at a single institute in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2003, 8: 26-30. 10.1007/s101470300003.

Broom A, Wijewardena K, Sibbritt D, Adams J, Nayar K: The use of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine in Sri Lankan cancer care: Results from a survey of 500 cancer patients. Public Health. 2010, 124: 232-237. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.02.012.

Lim C, Ng A, Loh K: Use of complementary and alternative medicine in head and neck cancer patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2010, 124: 529-532. 10.1017/S0022215109992817.

Pedersen CG, Christensen S, Jensen AB, Zachariae R: Prevalence, socio-demographic and clinical predictors of post-diagnostic utilisation of different types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of Danish women treated for primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009, 45: 3172-3181. 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.005.

Supoken A, Chaisrisawatsuk T, Chumworathayi B: Proportion of gynecologic cancer patients using complementary and alternative medicine. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009, 10: 779-782.

Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M: Gender, symptom experience, and use of complementary and alternative medicine practices among cancer survivors in the US cancer population. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010, 37: 7-15. 10.1188/10.ONF.S1.7-16.

Wyatt G, Sikorskii A, Wills CE, Su H: Complementary and alternative medicine use, spending, and quality of life in early stage breast cancer. Nurs Res. 2010, 59: 58-66. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181c3bd26.

Adams J: Researching Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007, Abingdon: Routledge

Ernst E: The prevalence of complementary/alternative medicine in cancer. Cancer. 1998, 83: 777-782. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980815)83:4<777::AID-CNCR22>3.0.CO;2-O.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Carole Do for her preliminary database searches and research which laid the groundwork for this study. This study was funded by the Centre for Complementary Medicine Research, University of Western Sydney, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BC searched the databases, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. CAS conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Carmady, B., Smith, C.A. Use of Chinese medicine by cancer patients: a review of surveys. Chin Med 6, 22 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8546-6-22

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8546-6-22