Abstract

Background

The present study investigates the effects of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 against 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), a neurotoxin on SH-SY5Y cells and PC-12 cells. The effects of these two ginsenosides on neuronal differentiation are also examined.

Methods

LDH assay was used to measure cell viability after exposure to 6-OHDA and ginsenosides. Neuronal differentiation was evaluated by changes in cell morphology and density of neurite outgrowths. Western blotting was used to determine the ginsenosides' effects on activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERKs).

Results

Rh1 and Rg2 attenuated 6-OHDA toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells and induced neurite outgrowths in PC-12 cells. 6-OHDA-induced ERK phosphorylation was decreased by Rh1 and Rg2. 20(R)-form and 20(S)-form of the ginsenosides exerted similar effects in inducing neurite outgrowths in PC-12 cells.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates neuroprotective effects of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 on neuronal cell lines. These results suggest potential Chinese medicine treatment for neurodegenerative disorders (eg Parkinson's disease).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a common motor system disorder characterized clinically by rigidity, resting tremor and slow movements [1]. It is associated with a progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons within the substantia nigra and depletion of dopamine in the striatal region [2, 3]. Dopamine (DA) is a catecholamine neurotransmitter in the brain, produced mainly in the substantia nigra and the ventral tegmental area. Six-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) is a hydroxylated analogue of DA. Metabolism of dopamine leads to the generation 6-OHDA [4, 5] which exerts specific neurotoxicity on catecholaminergic neurons by a selective transport mechanism, including its uptake and accumulation in those neurons [6] due to its structural similarity with DA. Recent studies demonstrated that 6-OHDA toxicity might involve an extracellular autoxidation process [6, 7]. Alterations in intracellular signaling pathways including the MAPKs pathway were recently found to accompany 6-OHDA toxicity. Specifically, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERK) activation and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation have been observed in various models [8–10].

Ginseng, the fleshy root of the Panax species in the family Araliaceae, is an herbal medicine traditionally used in East Asia and is now popular worldwide. Recent Studies have demonstrated its beneficial effects in vivo and in vitro in various pathological conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, immunodeficiency, cancer and hepatotoxicity [11]. Moreover, increasing evidence suggests that ginsenosides are responsible for the pharmacological effects of ginseng [12]. As ginsenosides (or ginseng saponins) possess antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory and immunostimulant properties; they can positively affect neurodegenerative diseases or delay neuronal aging [11]. In fact, ginsenosides have been reported to have various actions on the central nervous system (CNS) [13, 14], in particular, their anti-Parkinson effects. Ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 protect dopaminergic neurons in vivo and in vitro against toxicity induced by MPTP, 6-OHDA or glutamate [15–20]. They also enhance neurite outgrowth with or without stimulation of the nerve growth factor (NGF) [14, 18, 21]. Ginsenosides are classified into two major groups, namely dammarane and oleanane types [22]. Most ginsenosides belong to the dammarane type which is further divided into the protopanaxadiol (PPD) group and the protopanaxatriol (PPT) group according to their genuine aglycones [23]. Both ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 belong to the PPT group. While ginsenosides in the PPT group have generally stimulating effects on the CNS, such as anti-fatigue and hypertensive effects, anabolic stimulation, enhanced mental acuity and intellectual performance, ginsenosides in the PPD group are generally CNS-depressants with anti-stress, antipyretic and hypotensive effects [24]. However, the action mechanism of ginsenosides, Rh1 and Rg2 in particular, is still unclear. Each ginsenoside has 20(R) and 20(S) forms. However, the C-20 stereocytochemistry is relevant to the effects of ginsenosides still await investigation.

Nuclear receptors are transcriptional factors that specifically regulate target gene expression in response to hormones and other metabolic ligands [25]. Estrogen receptors (ERs), thyroid hormone receptor (TR), glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) are well-known subfamilies of nuclear receptors. The two ER subtypes, namely ERα and ERβ, together with their splice variants mediate diverse physiological processes in different tissues [26, 27] while ERα seems to be the major component in mediating neuroprotection and estrogen-induced differentiating effects [28, 29]. Previous studies revealed that liganded ERα enhanced NGF-induced differentiation in PC-12 cells while in the absence of 17β-estradiol (17βE2), the expression of ERα actually partly suppressed NGF-induced neurite outgrowth or expression of neuronal markers [30]. Increased NGF-induced gene expression by 17βE2 suggests the transcriptional activity of ERα on PC-12 cell differentiation. By contrast, several studies demonstrated that ERα was involved in the mediation of neuronal survival against various insulted including glutathione depletion, serum deprivation and glutamate toxicity [29, 31, 32].

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are an evolutionarily conserved family of serine/threonine-specific kinases that regulate various cellular activities, such as cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis [33, 34]. In mammals, MAPKs include the ERKs, p38 MAPK and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNKs) [35]. ERK's role in neurotoxicity is dependent on the experimental paradigm. Previous studies suggested that the activation of ERK by growth factors or by stress conferred a survival advantage to cells [36, 37]; however, recent studies found that ERK promoted neuronal cell death in vivo and in vitro[38, 39] while inhibition of ERK had protective effects in various models of neuronal cell death [40–42].

The present study aims to evaluate the effects of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 on neuroprotection, cell differentiation and on ERK activation in neuronal cells.

Methods

Chemicals

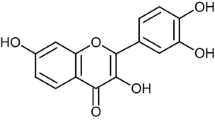

Ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 (enantiomeric mixtures) as well as individual stereoisomers, ie 20(R)-Rh1, 20(S)-Rh1, 20(R)-Rg2 and 20(S)-Rg2 in powder form (>99% purity) were provided by ZHJ (Figure 1). The powder was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a stock solution of 10 mM. Further dilution was made in complete culture medium or serum-free medium, depending on the experimental setup.

Nerve Growth Factor-β (NGF-β) from rat (Sigma-Aldrich; USA) was reconstituted using sterile PBS containing 0.1% BSA to a stock concentration of 1 μg/ml. Further dilution was made in complete culture medium or serum-free medium, depending on the experimental setup.

Six-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) hydrochloride (Sigma) was dissolved in sterile Hank's Buffered Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 0.1% ascorbic acid to a 1 mM stock solution, and further dilution to target concentrations was made in serum-free medium.

Cell culture

SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium containing nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) (Gibco; USA) with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Gibco; USA) and 0.5% Penicillin-Streptomycin-Neomycin (PSN) Antibiotic Mixture (Gibco; USA). The cells were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2. The culture medium was renewed every three to four days and the cells were subcultured every seven to eight days. The cells were detached from the culture flask by treatment with trypsin-EDTA (Gibco; USA) at a ratio of 1 ml per 25 cm2 for half a minute.

PC-12 cells were cultured in F-12 K Medium (Gibco; USA) with 15% Horse Serum (HS) (Gibco; USA), 2.5% FBS (Gibco; USA) and 1% PSN Antibiotic Mixture (Gibco). The cells were seeded on Type-I rat-tail collagen (Millipore; USA) coated culture flasks (Nunclon; USA), 6-well plastic plates (Iwaki; Japan) and 4-well plastic plates (Nunclon; USA). The cells were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2. The culture medium was renewed every three to four days and the cells were subcultured every seven to eight days. The cells were detached by physical flushing.

Neurite outgrowth assessments

PC-12 cells were seeded in 4-well plates at a density of 30,000 cells per well in complete culture medium. The medium was changed after 24 hours to complete the culture medium plus 20 μM ginsenoside Rh1 or Rg2 with or without 5 ng/ml NGF co-treatment. The concentration of NGF was chosen based on previous observations that 5 to 10 ng/ml NGF-β in serum-free medium induced optimal neurite outgrowth in PC-12 cells [26]. After 48 hours, the cells were observed under an inverted light microscope (ZEISS; Germary) at 200 × magnification and photos were taken for subsequent quantification of neurite outgrowth.

The cells were classified according to their morphology into three groups [43], namely (1) cells with long neuritis (ie cells with at least one neurite twice the length of its cell body diameter); (2) cells with short neuritis (ie cells without a long neurite but with at least one neurite that was longer than its cell body diameter); (3) cells without neuritis (ie cells without any neurite outgrowth that was longer than its cell body diameter. At least 120 cells were counted for each treatment. The percentages of each group of cells in each treatment were determined.

Analysis of cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity after 6-OHDA and/or ginsenosides exposure was quantitatively measured by LDH cytotoxicity assay with Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science; Germary). The cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 30,000 cells per well. For 6-OHDA and ginsenosides toxicity assay, 24 hours after seeding, the cells were washed once with serum-free medium, and then treated with different concentrations of 6-OHDA (5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 μM) or ginsenosides (10 and 20 μM of Rh1 or Rg2) for another 24 hours. Low control (serum-free medium) and high control (serum-free medium containing 2% Triton X-100) groups were set up to represent normal cell death and maximum cell death respectively. For the assay for ginsenosides' effects on 6-OHDA toxicity, 24 hours after seeding, the cells were pre-incubated in serum-free medium containing ginsenosides (10 and 20 μM of Rh1 or Rg2) for 24 hours. Then the cells were challenged with 6-OHDA (40 or 60 μM) with or without ginsenosides co-treatment for another 24 hours.

Prior to LDH assay, the 96-well plates were centrifuged (Beckman Allegra 6R; Beckman Instruments, USA) at 1000 g for 10 minutes to sediment the cells. Then 46 μl of supernatant was drawn from each well to a new empty well. The dye solution was mixed with the catalyst solution at a volume ratio of 45:1 and immediately after, 46 μl of reaction mixture was added to each well. The plate was incubated in the dark for 30 minutes, and then the optical density of the reaction mixture was measured with a multi-functional plate reader (Tecan Infinit F200; TECAN; Switzerland) at 495 nm with reference at 690 nm. The readings were normalized by subtracting the optical density of corresponding medium. The percentage of cell death (cytotoxicity) was calculated according to the following formula:

Western blot analysis of ERK1/2 activation

The cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1,000,000 cells per well in complete culture medium. For SH-SY5Y cells, treatment was applied 24 hours after seeding whereas for PC-12 cells, 24 hours after seeding the medium was changed to complete medium supplemented with 5 ng/ml NGF for 48 hours to induce differentiation. Treatment was done with serum-free medium for both cells. The cells were exposed to 20 μM ginsenoside for 24 hours and then 20 μM ginsenoside plus 50 μM 6-OHDA for 3 hours. The cells were washed by ice-cold PBS before lysed with lysis buffer containing Protein Extraction Reagent (Novagen; USA) and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set III (Calbiochem; USA) (200:1). The cell lysate was collected and centrifuged (5430R; Eppendorf; Germany) (14,000g,) at 4°C for 30 minutes. The supernatant containing the proteins was collected for protein quantification or storage at -80°C.

The protein concentration in the lysate was determined with a commercially available kit (Bio-Rad; USA) and calculated from a standard protein concentration curve. Protein samples were adjusted to equal concentration and volume by lysis buffer and then mixed with equal volume of sampler buffer (Bio-Rad; USA) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol by volume. The protein samples were heated at 100°C for five minutes before electrophoresis. The proteins were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel (4.5% stacking gel, 10% lower gel) and then transferred to Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Membrane (Bio-Rad; USA) overnight. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris buffered saline-Tween (TBST) solution. The membrane was then incubated with Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) or p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) antibody for two hours followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody for one hour. Bands on the PVDF membranes were visualized by a commercially available enhanced luminal-based chemiluminescent substrate (WESTSAVE UpTM; AbFrontier; Korea) and developed on films (Agfa; Germary). The integrated optical density (IOD) of bands was measured with Metamorph software (Universal Imaging Corporation; USA).

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Statistical differences between the treatment and control groups were analyzed by Welch's t-test with SigmaPlot 11.0 software (Systat Software, Inc.; Canada). For comparison between multiple groups, one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used followed by a Dunnett's post-hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

6-OHDA and ginsenosides cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity of 6-OHDA and ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 on SH-SY5Y cells was tested with the LDH assay. A significant increase (P = 0.010) in LDH release was observed following 24 hours of incubation with 6-OHDA at concentrations higher than 20 μM (Figure 2a), indicating that 6-OHDA exerted toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells. It may be suggested that the percentage of cell death increased in a dose-dependent manner within the range of 5 μM to 100 μM 6-OHDA. 50% cell death was estimated to occur at approximately 60 μM 6-OHDA (LC-50). Based on this experiment, two concentrations (40 μM and 60 μM) around and lower than the LC-50 were chosen for later experiments examining the effects of ginsenoside pretreatment on 6-OHDA toxicity.

Figures showing the effect of ginsenoside treatments on SH-SY5Y cells against 6-OHDA toxicity a. Six-hydroxydopamine toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells. The percentage of cell death (cytotoxicity) after 24 hours of exposure to different concentrations of 6-OHDA. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). (Welch's t-test, ** P = 0.010, ***P < 0.001, vs. control). Negative percentage is considered to be zero percentage as it is resulted by calculation of the LDH assay formula. b. Ginsenosides toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells. The percentage of cell death (cytotoxicity) after 24 hours of exposure to different concentrations of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 Values are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). The cytotoxicity of ginsenoside-treated groups and the control group was not significantly different (one way ANOVA, P = 0.110). c. Effect of ginsenoside pretreatment on 40 μM 6-OHDA toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells. The percentage of cell death (cytotoxicity) after 24 hours of pretreatment of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 (10 μM and 20 μM) followed by 24 hours co-treatment with ginsenosides together with 40 μM 6-OHDA. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). The cytotoxicity of ginsenoside-pretreated groups were not significantly different from that of the un-pretreated group (one way ANOVA, P = 0.184). d. Effect of ginsenoside pretreatment on 60 μM 6-OHDA toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells. The percentage of cell death (cytotoxicity) after 24 hours of pretreatment of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 (10 μM and 20 μM) followed by 24 hours co-treatment with ginsenosides together with 60 μM 6-OHDA. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). (Welch's t-test, *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, vs. un-pretreated group. 10 μM Rh1: P = 0.022; 10 μM Rg2: P = 0.002; 20 μM Rg2: P = 0.036).

No significant difference in LDH release was observed following 24 hours of incubation with the two ginsenosides (10 μM and 20 μM) comparing with the control group (Figure 2b). These two concentrations were used for subsequent experiments examining the effects of ginsenoside pretreatment on 6-OHDA toxicity.

Effects of ginsenoside pretreatment on 6-OHDA toxicity

A decrease in mean cytotoxicity was observed for ginsenoside-pretreated groups upon exposure to both 40 and 60 μM 6-OHDA. Statistical analysis showed that upon 40 μM 6-OHDA exposure, the mean toxicity for ginsenoside-pretreated groups were not significantly different (P = 0.184, One Way ANOVA) from that of the un-pretreated group (Figure 2c). However, upon 60 μM 6-OHDA exposure, the mean toxicity for three ginsenoside-pretreated groups (10 μM Rh1: 13.02 ± 4.26%; 10 μM Rg2: 11.86 ± 1.95%; 20 μM Rg2: 12.12 ± 5.57%) were found to be significantly different (P = 0.022 for 10 μM Rh1 and P = 0.036 for 20 μM Rg2; P = 0.002 for 10 μM Rg2) from that of the un-pretreated group (22.55 ± 1.61%; Figure 2d). These results suggest neuroprotective effects of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 against 6-OHDA toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells.

Neurite outgrowth assessment and morphological observation

The morphology of PC-12 cells was examined under inverted light microscope 48 hours after treatment. In their native states the PC-12 cells appear polygonal in shape and very few cells possess neurites while upon 5 ng/ml NGF exposure the cells extend obvious neurite outgrowths. Rh1 and Rg2 treatments both enhanced neurite outgrowths in the absence of NGF while their effects were potentiated with NGF co-treatment (Figure 3a). The morphological changes of PC12 cells were then quantified. After treatment with ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2, the percentage of PC12 cells possessing neurites was more than that of control. (Figure 3b).

Comparison of morphology and quantitative changes in PC-12 cells a. Morphology comparison of PC-12 cells with or without ginsenoside and/or NGF treatment. (A) Control; (B) 5 ng/ml NGF; (C) 20 μM Rh1; (D) 20 μM Rh1 + 5 ng/ml NGF; (E) 20 μM Rg2; (F) 20 μM Rg2 + 5 ng/ml NGF. Scale Bar: 50 mb. Quantitative changes in PC-12 cell morphology. The stacked bars illustrate the percentages of cells that do not possess neurites, possess short neurites only, or possess long neurites in each treatment group. At least 120 cells were counted for each treatment. Ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 (20 μM) both increased the percentage of cells possessing short or long neurites in the absence of NGF (Rh1: 20.3%, 6.5%; Rg2: 25.1%, 7.3%) compared to the control group (8.5%, 2.6%). In the presence of NGF (5 ng/ml) the effects of Rh1 and Rg2 were mostly enhanced, but were not greatly different from NGF treatment alone (Rh1+NGF: 26.8%, 10.8%; Rg2+NGF: 22.9%, 10.9%; NGF: 22.7%, 11.3%).

Inhibition of 6-OHDA-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation by ginsenosides

50 μM 6-OHDA induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in both SH-SY5Y cells and PC-12 cells after three hours of incubation while without 6-OHDA the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was barely detectable. Pretreatment with ginsenosides Rh1 (Figure 4) or Rg2 (Figure 5) for 24 hours reduced the levels of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in both cells. Statistical analysis (Welch's t-test) showed that the means of IODpERK /IODERK relative to the 6-OHDA control group were significantly reduced (SH-SY5Y :P < 0.001 for Rh1 and P = 0.015 for Rg2; PC-12: P = 0.027 for Rh1 and P < 0.001 for Rg2) with ginsenoside pretreatment (Figures 4 and 5). These results suggest a protective role of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 on both cells against 6-OHDA toxicity.

Inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation by ginsenosides Rh 1 and Rg 2 in SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Representative immunoblots showing the reduction in ERK1/2 phosphorylation by ginsenosides pretreatment in SH-SY5Y cells. (B) Bar chart showing reduction in IODpERK/IODERK of ginsenosides pretreated groups relative to the 6-OHDA control group (data presented as mean ± SD, n = 3). (Welch's t-test, * P = 0.015, *** P < 0.001).

Inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation by ginsenosides Rh 1 and Rg 2 in PC-12 cells. (A) Representative immunoblots showing the reduction in ERK1/2 phosphorylation by ginsenosides pretreatment in PC-12 cells. (B) Bar chart showing reduction in IOD pERK/IODERK of ginsenosides pretreated groups relative to the 6-OHDA control group (data presented as mean ± SD, n = 3). (Welch's t-test, * P = 0.027, *** P < 0.001).

Ginsenoside stereoisomers induce neurite outgrowth

Neurite outgrowth assessment in PC12 cells was repeated with the individual stereoisomers of ginsenosides, ie 20(R)-Rh1, 20(S)-Rh1, 20(R)-Rg2 and 20(S)-Rg2.

The percentage of cells possessing neuritis with the treatments of all four ginsenoside stereoisomers was found to be higher than that of control. And these treatments increased the neurite outgrowth in the absence of NGF while their effects potentiated with NGF co-treatments (Figure 6).

Comparison of ginsenoside stereoisomers' effects on PC-12 cell morphology. The stacked bars illustrate the percentages of cells that do not possess neurites, possess short neurites only, or possess long neurites in each treatment group. At least 160 cells were counted for each treatment. 20(R)-Rh1, 20(S)-Rh1, 20(R)-Rg2 and 20(S)-Rg2 (20 μM) all increased the percentage of cells possessing short or long neurites in the absence of NGF compared to the control group. In the presence of NGF (5 ng/ml) the neurite outgrowth were slightly enhanced, and no obvious difference in the effects were observed between 20(R)-ginsenosides and 20(S)-ginsenosides.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that 6-OHDA is cytotoxic to SH-SY5Y cells, and the toxicity increases in a dose-dependent manner. Pretreatment with ginsenosides Rh1 or Rg2 attenuates the 6-OHDA toxicity while not being toxic to the cells themselves. The results suggests that Rh1 and Rg2 may have induced changes in cellular activity, which helped the cells overcome 6-OHDA toxicity. It is well documented that oxidative stress is implicated in 6-OHDA-induced neuronal cell death [6, 17]. The pathophysiology of many neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's disease and PD are also closely associated with oxidative damage [44]. Neuroprotection can therefore be partly achieved by counteraction of the oxidative stress with various anti-oxidants, such as glutathione, flavonoids, estrogens and phytoestrogens [44–46]. Ginsenosides have been widely reported to have anti-oxidation activities [15–17] and to promote neurite outgrowth [14, 18]. A study by Liu et al. on the structure-activity relationship predicts that Rh1 is an anti-oxidant while Rg2 is a pro-oxidant [47]; however, Rg2 has been reported in other studies to have exhibited an anti-oxidation effect [46, 48]. To further elucidate the mechanisms of Rh1 and Rg2, we will investigate whether anti-oxidative activity plays a role here.

The neuroprotective effects of Rh1 and Rg2 were also exemplified in MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. 6-OHDA induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in SH-SY5Y cells as well as PC-12 cells, and the phosphorylation could be partly inhibited by pretreatment with Rh1 and Rg2. It has been reported that ginsenosides may bind to transmembrane membrane receptors to activate related signaling pathways downstream [49]. The MAPK-regulated kinases have a prominent role in regulating cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation and adaptation [8]. Activation of two families of MAPKs, JNK/SAPK and p38 MAPK is often correlated with neurodegeneration while the role of ERKs is less clear and may vary depending on the specific cell type [45]. In the 6-OHDA neuronal models, there seems to be a time course-dependent relationship between ERK phosphorylation and its effects. The first peak of phosphorylated ERK around 15 minutes after 6-OHDA treatment appears to be pro-survival whereas the second one that comes after several hours results from sustained mitochondrial ERK phosphorylation which enhances neuronal cell death [50, 51]. In the present study, significant ERK1/2 phosphorylation was found 3 hours after the 6-OHDA treatment, which is likely to be sustained rather than transient. However, we do not prelude that the change in ERK1/2 phosphorylation could be a biphasic response. The reduction of ERK1/2 phosphorylation by Rh1 or Rg2 pretreatment may indicate their neuroprotective effects against 6-OHDA toxicity. Another study also found similar inhibition effects on ERK1/2 phosphorylation exerted by Rg1[8].

In the present study, wild-type PC-12 cells were used as a model for neuronal differentiation. The result showed that ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 induced neurite outgrowth both in the absence and presence of NGF. However, the dose-response relationship and time-dependent changes, and whether this effect promotes neuroprotection remain to be determined. The synergistic effect between NGF and ginsenosides was not apparent, perhaps because the NGF concentration used was already very potent in inducing PC-12 cell differentiation, or perhaps the incubation time was not long enough for that to occur. The mechanism of neurite induction by ginsenosides is still undefined but may be related to nuclear receptor signaling.

Ginsenosides are steroidal saponins similar to estradiol in terms of their chemical structure (Figure 1). They have a rigid four trans-ring steroid skeleton, with a modified side-chain at C20 whereas estradiol does not possess a side-chain [52]. This structural similarity may be the cause for their similar activities as well, for instance, binding to the steroid hormone receptor ERα. Moreover, ginsenosides and estrogens share many of their target tissues. Previous studies have already demonstrated estrogen-like activity of several ginsenosides, including Rg1, Rb1 and Rh1; however, it remains controversial as to whether or not the activation of ERα is dependent on ligand binding [49, 52–55]. Nevertheless, the neuroprotective effects of estrogen also includes nongenomic mechanisms that may involve MAPK or Akt signaling, as well as its antioxidant ability, both of which may be ER-independent [56]. Thus, for the elucidation of the mechanisms of Rh1 and Rg2, further studies are warranted to test for their possible interactions with ERα (ligand binding assays; response genes expression). More investigations on ER-independent estrogen action may also contribute to our understanding of ginsenosides' estrogen-like effects.

Most ginsenosides isolated are present naturally as enantiomeric mixtures [57]. The structural factor involved is the stereochemistry at carbon-20 position. Recent studies showed that different stereoisomers of the same ginsenoside, ie 20(R)-ginsenoside and 20(S)-ginsenoside have different pharmacological effects [58, 59]. Conversely, the present study suggests that the neuroprotective properties of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 may not be related to their C-20 stereochemistry. Therefore, whether C-20 stereochemistry affects ginsenoside action may vary from case to case. Further investigation may delineate the structure-function relationship of ginsenosides.

Conclusion

6-OHDA induces cell death in SH-SY5Y cells in a dose-dependent manner while pre-incubation with ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 may attenuate such toxicity, possibly by anti-oxidation, activating nuclear receptors or modulations on intracellular signaling pathways. ERK1/2 phosphorylation is observed after 6-OHDA treatment in both SH-SY5Y cells and PC-12 cells. Pre-incubation with Rh1 or Rg2 reduces 6-OHDA-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which is possibly neuroprotective to the cells. Rh1 and Rg2 also induce neurite outgrowth in wild type PC-12 cells both in the presence and absence of NGF. C-20 stereochemistry does not play a part in the action of the two ginsenosides but their exact mechanism of neuroprotection remains unclear.

Abbreviations

- 17βE2:

-

17β-estradiol

- 6-OHDA:

-

6-hydroxydopamine

- JNK:

-

c-jun N-terminal kinase

- DA:

-

Dopamine

- DMEM/F12:

-

Dulbecco's modified eagle medium containing nutrient mixture F-12

- ERs:

-

Estrogen receptors

- ERKs:

-

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases

- GRs:

-

glucocorticoid receptors

- HS:

-

Horse Serum

- MAPKs:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- NGF:

-

nerve growth factor

- PD:

-

Parkinson's disease

- PSN:

-

Penicillin-Streptomycin-Neomycin

- PPD:

-

protopanaxadiol

- PPT:

-

protopanaxatriol

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TR:

-

thyroid hormone receptor

References

Warner TT, Schapira AH: Genetic and environmental factors in the cause of Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2003, 53 (Suppl 3): 16-25.

Davie CA: A review of Parkinson's disease. Br Med Bull. 2008, 86: 109-127. 10.1093/bmb/ldn013.

Hanrott K, Gudmunsen L, O'Neill MJ, Wonnacott S: 6-Hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis is mediated via extracellular auto-oxidation and caspase 3-dependent activation of protein kinase Cδ. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281: 5373-5382.

Linert W, Herlinger E, Jameson RF, Kienzl E, Jellinger K, Youdim MB: Dopamine, 6-hydroxydopamine, iron, and dioxygen--their mutual interactions and possible implication in the development of Parkinson's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996, 1316: 160-168.

Napolitano A, Crescenzi O, Pezzella A, Prota G: Generation of the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine by peroxidase/H2O2 oxidation of dopamine. J Med Chem. 1995, 38: 917-922. 10.1021/jm00006a010.

Soto-Otero R, Méndez-Alvarez E, Hermida-Ameijeiras A, Muñoz-Patiño AM, Labandeira-Garcia JL: Autoxidation and neurotoxicity of 6-hydroxydopamine in the presence of some antioxidants: potential implication in relation to the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2000, 74: 1605-1612.

Blum D, Torch S, Nissou MF, Benabid AL, Verna JM: Extracellular toxicity of 6-hydroxydopamine on PC12 cells. Neurosci Lett. 2000, 283: 193-196. 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)00948-4.

Ge KL, Chen WF, Xie JX, Wong MS: Ginsenoside Rg1 protects against 6-OHDA-induced toxicity in MES23.5 cells via Akt and ERK signaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127: 118-123. 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.038.

Li Z, Hu Y, Zhu Q, Zhu J: Neurotrophin-3 reduces apoptosis induced by 6-OHDA in PC12 cells through Akt signaling pathway. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2008, 26: 635-640. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2008.03.009.

Rodriguez-Blanco J, Martín V, Herrera F, García-Santos G, Antolín I, Rodriguez C: Intracellular signaling pathways involved in post-mitotic dopaminergic PC12 cell death induced by 6-hydroxydopamine. J Neurochem. 2008, 107: 127-140. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05588.x.

Rausch WD, Liu S, Gille G, Radad K: Neuroprotective effects of ginsenosides. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars). 2006, 66: 369-375.

Hasegawa H: Proof of the mysterious efficacy of ginseng: basic and clinical trials: metabolic activation of ginsenoside: deglycosylation by intestinal bacteria and esterification with fatty acid. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004, 95: 153-157. 10.1254/jphs.FMJ04001X4.

Chen CF, Chiou WF, Zhang JT: Comparison of the pharmacological effects of Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolium. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008, 29: 1103-1108. 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00868.x.

Rudakewich M, Ba F, Benishin CG: Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of ginsenosides Rb(1) and Rg(1). Planta Med. 2001, 67: 533-537. 10.1055/s-2001-16488.

Chen XC, Fang F, Zhu YG, Chen LM, Zhou YC, Chen Y: Protective effect of ginsenoside Rg1 on MPP+-induced apoptosis in SHSY5Y cells. J Neural Transm. 2003, 110: 835-845. 10.1007/s00702-003-0005-y.

Chen XC, Zhou YC, Chen Y, Zhu YG, Fang F, Chen LM: Ginsenoside Rg1 reduces MPTP-induced substantia nigra neuron loss by suppressing oxidative stress. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005, 26: 56-62. 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00019.x.

Hwang YP, Jeong HG: Ginsenoside Rb1 protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced oxidative stress by increasing heme oxygenase-1 expression through an estrogen receptor-related PI3K/Akt/Nrf2-dependent pathway in human dopaminergic cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010, 242: 18-28. 10.1016/j.taap.2009.09.009.

Radad K, Gille G, Moldzio R, Saito H, Ishige K, Rausch WD: Ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 effects on survival and neurite growth of MPP+-affected mesencephalic dopaminergic cells. J Neural Transm. 2004, 111: 37-45. 10.1007/s00702-003-0063-1.

Radad K, Gille G, Moldzio R, Saito H, Rausch WD: Ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 effects on mesencephalic dopaminergic cells stressed with glutamate. Brain Res. 2004, 1021: 41-53. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.030.

Xu L, Chen WF, Wong MS: Ginsenoside Rg1 protects dopaminergic neurons in a rat model of Parkinson's disease through the IGF-I receptor signalling pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2009, 158: 738-748. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00361.x.

Zou K, Zhu S, Meselhy MR, Tohda C, Cai S, Komatsu K: Dammarane-type Saponins from Panax japonicus and their neurite outgrowth activity in SK-N-SH cells. J Nat Prod. 2002, 65: 1288-1292. 10.1021/np0201117.

Christensen LP: Ginsenosides chemistry, biosynthesis, analysis, and potential health effects. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2008, 55: 1-99.

Tansakul P, Shibuya M, Kushiro T, Ebizuka Y: Dammarenediol-II synthase, the first dedicated enzyme for ginsenoside biosynthesis, in Panax ginseng. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580: 5143-5149. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.044.

Wild Rose College and Wholistic Clinic. [http://www.wrc.net/wrcnet_content/herbalresources/materiamedica/materiamedica.aspx?mmid=15]

McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O'Malley BW: Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999, 20: 321-344. 10.1210/er.20.3.321.

Katzenellenbogen BS, Choi I, Delage-Mourroux R, Ediger TR, Martini PG, Montano M, Sun J, Weis K, Katzenellenbogen JA: Molecular mechanisms of estrogen action: selective ligands and receptor pharmacology. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000, 74: 279-285. 10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00104-7.

Toran-Allerand CD: Minireview: A plethora of estrogen receptors in the brain: where will it end?. Endocrinology. 2004, 145: 1069-1074.

Dubal DB, Zhu H, Yu J, Rau SW, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Kindy MS, Wise PM: Estrogen receptor alpha, not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection against brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98: 1952-1957. 10.1073/pnas.041483198.

Mérot Y, Ferrière F, Debroas E, Flouriot G, Duval D, Saligaut C: Estrogen receptor alpha mediates neuronal differentiation and neuroprotection in PC12 cells: critical role of the A/B domain of the receptor. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005, 35: 257-267. 10.1677/jme.1.01826.

Mérot Y, Ferrière F, Gailhouste L, Huet G, Percevault F, Saligaut C, Flouriot G: Different outcomes of unliganded and liganded estrogen receptor-alpha on neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Endocrinology. 2009, 150: 200-211.

Gollapudi L, Oblinger MM: Stable transfection of PC12 cells with estrogen receptor (ERalpha): protective effects of estrogen on cell survival after serum deprivation. J Neurosci Res. 1999, 56: 99-108. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1<99::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-G.

Mize AL, Shapiro RA, Dorsa DM: Estrogen receptor-mediated neuroprotection from oxidative stress requires activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Endocrinology. 2003, 144: 306-312. 10.1210/en.2002-220698.

Raman M, Chen W, Cobb MH: Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene. 2007, 26: 3100-3112. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210392.

Zhang Y, Dong C: Regulatory mechanisms of mitogen-activated kinase signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007, 64: 2771-2789. 10.1007/s00018-007-7012-3.

Wang YZ, Bonner JC: Mechanism of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-1 and ERK-2 activation by vanadium pentoxide in rat pulmonary myofibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000, 22: 590-596.

Wang X, Martindale JL, Liu Y, Holbrook NJ: The cellular response to oxidative stress: influences of mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways on cell survival. Biochem J. 1998, 333: 291-300.

Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME: Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995, 270: 1326-1331. 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326.

Stanciu M, Wang Y, Kentor R, Burke N, Watkins S, Kress G, Reynolds I, Klann E, Angiolieri MR, Johnson JW, DeFranco DB: Persistent activation of ERK contributes to glutamate-induced oxidative toxicity in a neuronal cell line and primary cortical neuron cultures. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 12200-12206. 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12200.

Subramaniam S, Zirrgiebel U, von Bohlen , Halbach O, Strelau J, Laliberté C, Kaplan DR, Unsicker K: ERK activation promotes neuronal degeneration predominantly through plasma membrane damage and independently of caspase-3. J Cell Biol. 2004, 165: 357-369. 10.1083/jcb.200403028.

Lu K, Liang CL, Liliang PC, Yang CH, Cho CL, Weng HC, Tsai YD, Wang KW, Chen HJ: Inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK)1/2 provides neuroprotection in spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats: relationship with the nuclear factor-κB-regulated antiapoptotic mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2010, 114: 237-246.

Satoh T, Nakatsuka D, Watanabe Y, Nagata I, Kikuchi H, Namura S: Neuroprotection by MAPK/ERK kinase inhibition with U0126 against oxidative stress in a mouse neuronal cell line and rat primary cultured cortical neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2000, 288: 163-166. 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01229-5.

Wang X, Wang H, Xu L, Rozanski DJ, Sugawara T, Chan PH, Trzaskos JM, Feuerstein GZ: Significant neuroprotection against ischemic brain injury by inhibition of the MEK1 protein kinase in mice: exploration of potential mechanism associated with apoptosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003, 304: 172-178. 10.1124/jpet.102.040246.

Lustig RH, Hua P, Yu W, Ahmad FJ, Baas PW: An in vitro model for the effects of estrogen on neurons employing estrogen receptor-transfected PC12 cells. J Neurosci. 1994, 14: 3945-3957.

Ossola B, Kääräinen TM, Raasmaja A, Männistö PT: Time-dependent protective and harmful effects of quercetin on 6-OHDA-induced toxicity in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells. Toxicology. 2008, 250: 1-8. 10.1016/j.tox.2008.04.001.

Behl C, Skutella T, Lezoualc'h F, Post A, Widmann M, Newton CJ, Holsboer F: Neuroprotection against oxidative stress by estrogens: structure-activity relationship. Mol Pharmacol. 1997, 51: 535-541.

Li N, Liu B, Dluzen DE, Jin Y: Protective effects of ginsenoside Rg2 against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 111: 458-463. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.12.015.

Liu ZQ, Luo XY, Liu GZ, Chen YP, Wang ZC, Sun YX: In vitro study of the relationship between the structure of ginsenoside and its antioxidative or prooxidative activity in free radical induced hemolysis of human erythrocytes. J Agric Food Chem. 2003, 51: 2555-2558. 10.1021/jf026228i.

Samukawa K, Suzuki Y, Ohkubo N, Aoto M, Sakanaka M, Mitsuda N: Protective effect of ginsenosides Rg(2) and Rh(1) on oxidation-induced impairment of erythrocyte membrane properties. Biorheology. 2008, 45: 689-700.

Lee Y, Jin Y, Lim W, Ji S, Choi S, Jang S, Lee S: A ginsenoside-Rh1, a component of ginseng saponin, activates estrogen receptor in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003, 84: 463-468. 10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00067-0.

Kulich SM, Horbinski C, Patel M, Chu CT: 6-Hydroxydopamine induces mitochondrial ERK activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007, 43: 372-383. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.04.028.

Lin E, Cavanaugh JE, Leak RK, Perez RG, Zigmond MJ: Rapid activation of ERK by 6-hydroxydopamine promotes survival of dopaminergic cells. J Neurosci Res. 2008, 86: 108-117. 10.1002/jnr.21478.

Chan RY, Chen WF, Dong A, Guo D, Wong MS: Estrogen-like activity of ginsenoside Rg1 derived from Panax notoginseng. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87: 3691-3695. 10.1210/jc.87.8.3691.

Cho J, Park W, Lee S, Ahn W, Lee Y: Ginsenoside-Rb1 from Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer activates estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta, independent of ligand binding. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89: 3510-3515. 10.1210/jc.2003-031823.

Lau WS, Chan RY, Guo DA, Wong MS: Ginsenoside Rg1 exerts estrogen-like activities via ligand-independent activation of ERalpha pathway. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008, 108: 64-71. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.06.005.

Lee YJ, Jin YR, Lim WC, Park WK, Cho JY, Jang S, Lee SK: Ginsenoside-Rb1 acts as a weak phytoestrogen in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2003, 26: 58-63. 10.1007/BF03179933.

Dhandapani KM, Brann DW: Protective effects of estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators in the brain. Biol Reprod. 2002, 67: 1379-1385. 10.1095/biolreprod.102.003848.

Soldati F, Sticher O: HPLC separation and quantitative determination of ginsenosides from Panax ginseng, Panax quinquefolium and from ginseng drug preparations. 2nd communication. Planta Med. 1980, 39: 348-357. 10.1055/s-2008-1074929.

Kang DI, Lee JY, Yang JY, Jeong SM, Lee JH, Nah SY, Kim Y: Evidence that the tertiary structure of 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg(3) with tight hydrophobic packing near the chiral center is important for Na(+) channel regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005, 333: 1194-1201. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.026.

Liu J, Shiono J, Shimizu K, Yu H, Zhang C, Jin F, Kondo R: 20(R)-ginsenoside Rh2, not 20(S), is a selective osteoclastgenesis inhibitor without any cytotoxicity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009, 19: 3320-3323. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.054.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Hong Kong Baptist University Research Committee Mini-Area of Excellence Scheme RC/AOE/08-09/02 (to KKLY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

XFL and KKLY designed the study. XFL conducted the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. CNPL revised the manuscript. ZHJ helped conduct the experiments. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, XF., Lui, C.NP., Jiang, ZH. et al. Neuroprotective effects of ginsenosides Rh1 and Rg2 on neuronal cells. Chin Med 6, 19 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8546-6-19

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8546-6-19