Abstract

Background

The aim of the present study was to investigate epidemiological data about cigarette smoking in relation with risk and preventive factors among Greek adolescents.

Methods

We randomly selected 10% of the whole number of schools in Northern Greece (133 schools, 18,904 participants were included). Two anonymous questionnaires (smoker's and non-smoker's) were both distributed to all students so they selected and filled in only one. A parental signed informed consent was obtained using an informative leaflet about adolescent smoking.

Results

The main findings of the study were: a) 14.2% of the adolescents (mean age+/−SD: 15.3+/−1.7 years) reported regular smoking (24.1% in the age group 16–18 years), b) 84.2% of the current smokers reported daily use, c) students who live in urban and semirural areas smoke more frequently than those in rural areas, d) students in technically oriented schools smoke twice as frequent compared to those in general education, e) risk factors for smoking: male gender, low educational level of parents, friends who smoke (OR: 10.01, 95%CI: 8.53-11.74, p<0.001), frequent visits to internet cafes (OR:1.53, 95%CI: 1.35-1.74, p<0.001), parents, siblings (OR:2.24, 95%CI: 1.99-2.51, p<0.001) and favorite artist (OR:1.18, 95%CI: 1.04-1.33, p=0.009) who smoke, f) protective factors against smoking: participation in sports (OR:0.59, 95%CI: 0.53-0.67, p<0.001), watching television (OR:0.74, 95%CI 0.66-0.84, p<0.001) and influence by health warning messages on cigarette packets (OR:0.42, 95%CI: 0.37, 0.48, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Even though prevalence of cigarette smoking is not too high among Greek adolescents, frequency of everyday cigarette use is alarming. We identified many social and lifestyle risk and preventive factors that should be incorporated in a national smoking prevention program among Greek adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cigarette smoking is considered a modern epidemic with incalculable consequences for public health and economy. It was estimated that in 2008, smoking was responsible for the death of more than 5 million people worldwide - more than those caused by tuberculosis, AIDS and malaria together - and it is expected that in the 21st century this number will approach 1 billion unless antismoking measures will be taken [1]. The use of tobacco is the world's leading cause of morbidity and premature mortality that can be prevented [2].

Smoking experimentation is related to adolescence as adolescents are more influenced by their social environment [3]. Almost all adults who smoke regularly report that they started at or before age 18 [4], adolescents are less likely to quit smoking [5, 6] as symptoms of nicotine dependence can easily be developed [7]. The prevalence of current smoking among adolescents in the USA and in many European countries is well above the established targets for the near future [8, 9].

Many social and psychological factors have been positively related with adolescent smoking: parental and peer smoking [10, 11], poor performance in school [12], low socioeconomic conditions [13, 14], childhood abuse [15, 16], exposure to films or advertisements which promote smoking [17–20], anxiety [21] and depression [22]. On the other hand there are some protective factors even though data are not so robust. Parents or friends who do not smoke [23, 24], negative beliefs about smoking [24], sports participation [25] and religious identity [26].

The aim of the present study was to investigate epidemiological trends about cigarette smoking as well as psychosocial differences between adolescents (12–18 years) smokers and non-smokers that may act as preventive or risk factors. A secondary aim of the study was the validation of two questionnaires – one for smokers and another one for non-smokers – in a subgroup of the initial sample.

Methods

Design

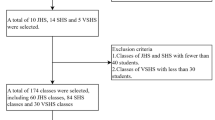

Initially, a special proposal-application was submitted to the Ministry of Education, requesting permission so that a questionnaire on smoking habits may be answered by students (12–18 year old) in junior high and high schools of Northern Greece. After the approval was obtained, we used summary lists of all junior high and high schools in the prefectures of Macedonia (13 counties), Thrace (3 counties), Thessaly (4 counties) and Epirus (4 counties). The exact number of schools, the type of school (e.g. general or technical education, morning or evening shift) and the number of students was reported.

This is a surveillance study with a reference population consisted of 1,341 schools. Then we excluded schools for children with mental disabilities, church-schools and evening schools that enrolled mostly adults. We randomly selected 10% of the original sample of schools and the present study was conducted in 133 schools. The degree of reproducibility was assessed by recompletion of the questionnaires – over a period of two weeks – in 10% of the schools that had been selected (13 schools). Finally we distributed the questionnaires to the whole sample of the study which was conducted from November 2009 to May 2010.

Questionnaires

A parental signed informed consent was obtained using an informative leaflet about adolescent smoking and the questionnaire their children are going to complete. For the purpose of the study two questionnaires were prepared: one for smokers and the other one for non-smokers (see Additional file 1). The questionnaires were anonymous, were both distributed simultaneously to all students so they selected and filled in only one of them.

The students completed the questionnaires in the classroom under examination conditions, the teacher was absent while the researcher explained in detail all questions and the children wrote their answers. At the end of the survey, each child sealed the completed questionnaire in an envelope. This whole procedure was designed in such a way to emphasize that their answers were confidential. The main advantage of the questionnaires was that the average time to be completed was 10–15 minutes. After completion of the questionnaires, doctors who took part in the study gave lectures about the consequences of cigarette smoking on human health and the importance of early cessation.

Questions about anthropometric data, patterns of smoking behaviour, parents’ educational level, smoking habits of family and social environment, leisure activities, possible causes of initiation or abstinence, proposals for anti-smoking measures were included. The majority of the questions had predefined answers to promote convenience and participation while several questions were the same in both questionnaires. Current cigarette smoker was considered every participant who had smoked at least one cigarette during the month before completing the questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

Reproducibility for each question was assessed using the Cohen’s kappa statistic. As an overall rate of reproducibility for the entire questionnaire the mean of the Cohen’s kappa statistic and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals were reported. Initially, the test Kolmogorov-Smirnov was used in the quantitative variables to determine if the data was normally distributed. The percentages were compared by chi-square test. Student’s t test was applied to compare two groups when data were normally distributed; otherwise the corresponding non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was applied. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the corresponding non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare groups of three or more. The association of smoking with other factors was estimated with random-effects logistic regression in order to take into account the clustering of schools. First univariate analysis was performed and the final multivariable model was selected after backward elimination method with the likelihood criteria. STATA version 12.0 was used for this analysis. In all statistical tests the level of significance was set at 0.05 and two-sided. The statistical analysis applied to the statistical package SPSS 17.0.

Results

The initial sample size of the study consisted of 19,572 students. We gathered 19,027 questionnaires (participation rate: 97.2%). Non-participation was due to absence from school on the day of the study (e.g. illness, participation in sports or cultural activities). None of the students who were present at school refused to complete the questionnaire. One hundred and twenty three questionnaires were not suitable for analysis (e.g. age > 18 years old, silly/illogical/inadequately (<3 questions) answered: 1 million cig./day, tick both YES and NO answers). Finally the data of 18,904 questionnaires were encoded and statistically analysed.

We calculated the reproducibility rate of both questionnaires among 1,791 students (10% of the total number of the study’s schools). Reproducibility as assessed by the Cohen’s kappa statistic for the questionnaire of smokers and non-smokers was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.85, 0.90) and 0.88 (95% CI: 0.86, 0.91) respectively.

Concerning the whole study sample (n = 18,904, mean age ± SD: 15.3 ± 1.7 years), 2,685 students (14.2%) completed the smokers’ questionnaire which was equivalent with regular cigarette smoking. Of these, 2,245 (83.6%) reported everyday consumption (15.7 ± 10.6 cigarettes/day), 414 (15.4%) reported regular use but not every day (40.1 ± 72.9 cigarettes for the last month) and 26 students were current smokers but they had not given any information about their smoking habits. On the other hand 4,984 students of the current non-smokers reported that they had tried sometimes in the past (mean age ± SD: 13.9 ± 2.3 years). The percentage of lifetime cigarette use was 40.6% (7,669/18,904).

We initially compared smoking habits according to gender, school type and area of residence. Boys smoke more frequently than girls (16.4% vs 11.8%, p < 0.001, Table 1) while the percentage of students in high schools with technical education who reported regular smoking was more than double compared to that in general high schools (36.7% vs 17.8%, p < 0.001, Table 1). The above comparison did not include junior high schools due to low number of students in junior high schools with technical education (n = 198).

In urban (city of Thessaloniki) and semirural areas (counties’ capitals) the incidence of smoking was higher than rural regions (p < 0.001, Table 1). It is worth noting that in urban area the percentage of smoking was similar between boys and girls (16.6% vs 15.4%, p = 0.207) while smoking prevalence among boys was significantly higher compared to girls in rural and semirural regions (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). The daily cigarette consumption was different among areas of residence (14.7 ± 9.8 for Thessaloniki, 16.5 ± 10.9 for semirural and 15.7 ± 11.1 for rural areas, p = 0.005, Kruskal-Wallis test).

Boys start smoking regularly at an earlier age compared to girls although the mean difference is only a few months (14.4 ± 1.9 vs 14.8 ± 1.5 years old, p < 0.001, Student’s t-test: 5.05, df: 2608). On the other hand the age of starting smoking did not differ among the three areas of residence (14.7 ± 1.7 vs 14.5 ± 1.8 vs 14.5 ± 1.8 years old respectively, p = 0.133, ANOVAF-test: 2.02, dfb/dfw: 2/2619).

We defined addiction to nicotine as consumption of more than 15 cigarettes/day and the first one within 30–60 minutes after awaking. We calculated that almost a third (32.8%) of the smokers fulfil the above criteria (Table 2). Curiosity and a way to deal with unpleasant feelings (e.g. nervousness, anxiety and anger) were the most reported causes for starting smoking (Table 3). Regarding the question about what smokers dislike in relation with smoking, the most popular answers were: the high price of cigarettes (55.7%), bad breath and clothes smell (50.3%) and harmful effect on my health (48.7%).

The associations of different factors with smoking status are presented in Table 4. Friends who smoke was proved to be the most important risk factor (OR: 10.01, 95% CI: 8.53-11.74, p < 0.001, Wald χ2 = 2562.15; df = 15). In multivariable analysis, the odds of smoking was higher in male gender, with higher age, with greater BMI, with frequent visits to internet cafes, when parents, siblings, friends and favorite artist smoked (Table 4). On the other hand, participation in sports, watching television and influence by health warning messages on cigarette packets act as protective factors against smoking (Table 4). An interesting finding was that knowledge about smoking related diseases was quite similar between the two groups. Higher percentages of non-smokers compared to smokers reported that anti-smoking measures are necessary (96% vs 68.3%, p < 0.001; Table 4). More specifically, the most popular answers were: prohibition of smoking in public places and workplaces (smokers: 31.5% vs non-smokers: 73.7%, p < 0.001, x2-test: 1580.31; df:1), prohibiting of cigarettes’ selling to people ≤17 years old (smokers: 43% vs non-smokers: 69.7%, p < 0.001, x2-test: 606.35; df:1) and informative campaign about the consequences of smoking on human health (smokers: 36.8% vs non-smokers: 58.4%, p < 0.001, x2-test: 361.71; df:1).

Finally we tried to correlate intensity of smoking (number of cigarettes per day) with various social factors reported in the questionnaires. Smoking status of father (14.7 ±10.2 cig./day if father does not smoke vs 16.2 ±10.8 cig./day if father smokes, p = 0.001; Mann–Whitney U test: -3.38), mother (14.8 ±10 vs 16.6 ±11.1, p < 0.001), siblings (14.7 ±10.2 vs 17.1 ±11.1, p < 0.001; Mann–Whitney U test: -3.97), educational level of father (15.4 ±11.3 cig./day for the university degree vs 17.7 ±12.4 cig./day for the lowest score elementary school, p = 0.001; Mann–Whitney U test: -3.37) and educational level of mother (15.1 ±10.5 vs 17.6 ±11.5, p = 0.001; Mann–Whitney U test: -3.39) were associated with smoking intensity of the adolescents. We also found that those who visit more frequently internet café (17.8 ±12.2 cig./day vs 13.7 ±8.7, p < 0.001; Mann–Whitney U test: -6.10) and were not influenced by the messages on cigarette packets (16.2 ±10.5 cig./day vs 13.6 ±10.6, p < 0.001; Mann–Whitney U test: -5.80) used to smoke more. Adolescents whose parents know that they smoke used to consume more cigarettes daily (17.8 ±10.9 vs 10.9 ±8.1, p < 0.001; Mann–Whitney U test: -15.98).

Discussion

To our current knowledge this is the largest – according to the number of participants – epidemiological study in Greece about cigarette smoking among adolescents. The main findings of the present study are: a) 14.2% of the adolescents (mean age ± SD: 15.3 ± 1.7 years) reported regular smoking (24.1% in the age group 16–18 years), b) 40.6% reported lifetime cigarette use, c) 84.2% of the current smokers reported daily cigarette use, d) students who live in urban and semirural areas smoke more frequently than those in rural areas, e) students in technically oriented schools smoke twice as frequent compared to those in general education, f) we identified as risk factors for smoking: male gender, age, friends who smoke, frequent visits to internet cafés, parents, siblings and favourite artist who smoke, educational level of the parents (Table 4), g) we identified as protective factors against smoking: participation in sports, watching television and influence by health warning messages on cigarette packets (Table 4). The same factors are related with the intensity of smoking (cigarettes/day) as well as the presence of parents who are aware that their child smokes.

In a cross-sectional national survey in the USA among high school students it was found that the percentage of current smokers was 20% (21.3% for males and 18.7% for females) in 2007 while 8.1% reported smoking on 20 or more days during the last 30 days [8]. In our study the percentage of current smokers among high school students was 24.1% (27.2% for males and 20.4% for females) while the percentage of everyday smokers was 21% (1,885/8,960). In the Global Youth Tobacco Survey [9], which was conducted among students 13–15 years old, it was found that 9.5% of the participants were current smokers (19.2% for eastern European countries, 10.4% cigarette smoking for Greece in 2005 and 4.9% for the eastern Mediterranean region). In our study the percentage of current smokers among junior high school students was 5.1%.

Several studies have concluded that the risk for an adolescent to become a current smoker is increased if their parents [10, 27–29], siblings [28, 29] or best friends [28, 29] smoke. In a recent meta-analyses which included 58 studies [30], the relative odds of uptake of smoking in children were increased significantly if at least one parent smoked (OR: 1.72, 95% CI 1.59-1.86), more so by smoking by the mother (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.73-2.79) than the father (OR: 1.66, 95% CI 1.42-1.94) while smoking by a sibling increased the odds of smoking uptake by 2.30 (95% CI 1.85-2.86). In a recent review that investigated the relationship between participation in sports and smoking among adolescents, 14 out of 15 studies had found an inverse relationship [25]. The above findings are in accordance with our conclusions.

A recent study among adolescents in high schools in Thessaloniki, Greece found that physical activity was negatively correlated with smoking, whereas drinking alcohol and low parental education were positively correlated [31]. Damianaki et al [32] conducted a cross-sectional study in a sample of 924 students (12–18 years old) in a semi-urban area in Crete, Greece and found that 11.4% of the total sample was daily smokers (2,245/18,904 = 11.9% in our study) while there was positive relationship between current smoking and having brother or sister smoking (odds ratio: 2.7 (95% CI: 1.7-4.4) and 1.8 (1.1-3.3) respectively), having more than three friends who were smokers (OR: 2.6 (95% CI: 2–3.4) and last school grade [OR:1.4 (95% CI: 1.2-1.7)]. The Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) was conducted in Greece [33, 34] among 6,378 students (13–15 years old) during the academic year 2004–5. The authors found that 16.4% of the students reported being current users of tobacco products, 10.4% were current smokers of cigarettes while male gender (OR: 1.62; 95% CI: 1.08-3.08), parental smoking (OR: 2.59; 95% CI: 1.45-5.89), and having pocket money ≥ 16 Euros (OR:2.64; 95% CI: 1.19-5.98) proved to be independent risk factors associated with current cigarette smoking. In our study, which included adolescents 12–18 years old, the prevalence of current cigarette smoking was 14.2% while we also found similar risk factors as the above mentioned studies. Additionally we identified some important protective factors.

Regarding risk factors a study of Russian adolescents found that behavioral activation increased conflict with parents and a tendency to go to clubs and bars, both of which increased cigarette use [35]. In the present study frequent (≥3 times/week) visits to internet cafés significantly increased the risk for smoking. Low socioeconomic status has been associated with greater cigarette smoking in several studies [36]. In our study educational level of the parents, which is usually an indirect index of socioeconomic status, was not related with adolescents’ cigarette use.

A recent systematic review [37] showed that media exposure was associated with increased risk of smoking initiation even though we found that watching television everyday was a protective factor against smoking. We hypothesized that prohibition of cigarette advertising on TV as well as educational programs about smoking related diseases could be an explanation. A report by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [38] in 14 countries about the effectiveness of cigarette package health warnings concluded that percentage of adult smokers thinking about quitting because of the warnings was >50% in six countries. Similarly we found that messages on cigarette packets act as a protective factor against smoking for adolescents.

We should mention that using two different questionnaires is not a common practice for most epidemiological studies and this could be considered a limitation. We decided to use two questionnaires because we thought that this would increase response rate and minimize time required for completion. As the percentages of current and lifetime cigarette smokers among Greek adolescents were quite high effective smoking prevention programs are urgently needed. The present study proved that many risk and protective social factors should be taken into account.

References

WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic: The MPOWER package. 2008, World Health Organization, Geneva

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention: Annual smoking -attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs - United States, 1995–1999. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2002, 51: 300-303.

Kandel DB, Andrews K: Processes of adolescent socialization by parents and peers. Int J Addict. 1987, 22: 319-342.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Cigarette use among high school students—United States, 1991–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006, 55 (26): 724-726.

Breslau N, Peterson EL: Smoking cessation in young adults: age at initiation of cigarette smoking and other suspected influences. Am J Public Health. 1996, 86: 214-220. 10.2105/AJPH.86.2.214.

Bancej C, O'Loughlin J, Platt RW: Smoking cessation attempts among adolescent smokers: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Tob Control. 2007, 16 (6): e8-10.1136/tc.2006.018853.

O’Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF: Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2003, 25: 219-225. 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00198-3.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Cigarette use among high school students-United States, 1991-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008, 57: 686-688.

Warren CW, Jones NR, Peruga A: Global Youth Tobacco Surveillance, 2000-2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008, 57: 1-28.

Taylor JE, Conard MW, O’Byrne KK: Saturation of tobacco smoking models and risk of alcohol and tobacco use among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004, 35: 190-196.

Molyneux A, Lewis S, Antoniak M: Prospective study of the effect of exposure to other smokers in high school tutor groups on the risk of incident smoking in adolescence. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 159: 127-132. 10.1093/aje/kwh035.

Van Den Bree M, Whitmer M, Pickworth W: Predictors of smoking development in a population based sample of adolescents: a prospective study. J Adolesc Health. 2004, 35: 172-181.

Jefferis B, Power C, Graham H: Effects of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on persistent smoking. Am J Public Health. 2004, 94: 279-285. 10.2105/AJPH.94.2.279.

Barnett JR: Does place of residence matter? Contextual effects and smoking in Christchurch. N Z Med J. 2000, 113: 433-435.

Nichols HB, Harlow BL: Childhood abuse and risk of smoking onset. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004, 58: 402-406. 10.1136/jech.2003.008870.

Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ: Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999, 282: 1652-1658. 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652.

Morgenstern M, Poelen EAP, Scholte R: Smoking in movies and adolescent smoking: cross-cultural study in six European countries. Thorax. 2011, 66: 875-883. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200489.

Waylen AE, Leary SD, Ness AR: Cross- sectional association between smoking depictions in films and adolescent tobacco use nested in a British cohort study. Thorax. 2011, 66: 856-861. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200053.

Hanewinkel R, Isensee B, Sargent JD: Cigarette advertising and teen smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2011, 127: 271-278. 10.1542/peds.2010-2934.

Braverman MT, Aarø LE: Adolescent smoking and exposure to tobacco marketing under a tobacco advertising ban: findings from 2 Norwegian national samples. Am J Public Health. 2004, 94: 1230-1238. 10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1230.

Henker B, Whalen CK, Jamner LD: Anxiety, affect, and activity in teenagers: Monitoring daily life with electronic diaries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002, 41: 660-670. 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00005.

Haarasilta LM, Marttunen MJ, Kaprio JA: Correlates of depression in a representative nationwide sample of adolescents (15–19 years) and young adults (20–24 years). Eur J Public Health. 2004, 14: 280-285. 10.1093/eurpub/14.3.280.

Emory K, Saquib N, Gilpin EA: The association between home smoking restrictions and youth smoking behavior: a review. Tob Control. 2010, 19: 495-506. 10.1136/tc.2010.035998.

Cengelli S, O'Loughlin J, Lauzon B: A systematic review of longitudinal population-based studies on the predictors of smoking cessation in adolescent and young adult smokers. Tob Control 2011 Aug 16. Tob Control. 2011, 21: 355-362.

Lisha NE, Sussman S: Relationship of high school and college sports participation with alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use: A review. Addict Behav. 2010, 35: 399-407. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.032.

Soweid RAA, Khawaja M, Salem MT: Religious identity and smoking behavior among adolescents: evidence from entering students at the American University of Beirut. Health Commun. 2004, 16: 47-62. 10.1207/S15327027HC1601_4.

Jarvelaid M: Adolescent tobacco smoking and associated psychosocial health risk factors. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2004, 22: 50-53. 10.1080/02813430310000988.

Can G, Topbas M, Oztuna F: Factors contributing to regular smoking in adolescents in Turkey. J Sch Health. 2009, 79: 93-97. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.0392.x.

Karp I, Paradis G, Lambert M: A prognostic tool to identify adolescents at high risk of becoming daily smokers. BMC Pediatr. 2011, 11: 70-10.1186/1471-2431-11-70.

Leonardi-Bee J, Jere ML, Britton J: Exposure to parental and sibling smoking and the risk of smoking uptake in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2011, 66: 847-855. 10.1136/thx.2010.153379.

Arvanitidou M, Tirodimos I, Kyriakidis I: Cigarette smoking among adolescents in Thessaloniki, Greece. Int J Public Health. 2008, 53: 204-207. 10.1007/s00038-008-8001-5.

Damianaki A, Kaklamani S, Tsirakis S: Risk factors for smoking among school adolescents in Greece. Child Care Health Dev. 2008, 34: 310-315. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00839.x.

Kyrlesi A, Soteriades ES, Warren CW: Tobacco use among students aged 13–15 years in Greece: the GYTS project. BMC Publ Health. 2007, 7: 3-10.1186/1471-2458-7-3.

Rachiotis G, Muula AS, Rudatsikira E: Factors associated with adolescent cigarette smoking in Greece: Results from a cross sectional study (GYTS Study). BMC Publ Health. 2008, 8: 313-10.1186/1471-2458-8-313.

Knyazev GG: Behavioral activation as predictor of substance use: mediating and moderating role of attitudes and social relationships. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004, 75: 309-321. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.007.

Hanson MD, Chen E: Socioeconomic status and health behaviors in adolescence: a review of the literature. J Behav Med. 2007, 30: 263-285. 10.1007/s10865-007-9098-3.

Nunez-Smith M, Wolf E, Huang HM: Media exposure and tobacco, illicit drugs, and alcohol use among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2010, 31: 174-192. 10.1080/08897077.2010.495648.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Cigarette package health warnings and interest in quitting smoking - 14 countries 2008-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011, 60: 645-651.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Hellenic Thoracic Society.

The present study was presented in a poster discussion session during the European Respiratory Society Congress 2011.

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in JECH editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

DGS, DTP, DC, AHB, and LTS conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. EK, and KG, draft the article or revise it critically for important intellectual content. SK and CK final approval of the version published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Spyratos, D.G., Pelagidou, D.T., Chloros, D. et al. Smoking among adolescents in Northern Greece: a large cross-sectional study about risk and preventive factors. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 7, 38 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-7-38

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-7-38