Abstract

Background

Swine barn air contains endotoxin and many other noxious agents. Single or multiple exposures to pig barn air induces lung inflammation and loss of lung function. However, we do not know the effect of exposure to pig barn air on inflammatory response in the lungs following a secondary infection. Therefore, we tested a hypothesis that single or multiple exposures to barn air will result in exaggerated lung inflammation in response to a secondary insult with Escherichia coli LPS (E. coli LPS).

Methods

We exposed Sprague-Dawley rats to ambient (N = 12) or swine barn air (N = 24) for one or five days and then half (N = 6/group) of these rats received intravenous E. coli LPS challenge, observed for six hours and then euthanized to collect lung tissues for histology, immunohistochemistry and ELISA to assess lung inflammation.

Results

Compared to controls, histological signs of lung inflammation were evident in barn exposed rat lungs. Rats exposed to barn air for one or five days and challenged with E. coli LPS showed increased recruitment of granulocytes compared to those exposed only to the barn. Control, one and five day barn exposed rats that were challenged with E. coli LPS showed higher levels of IL-1β in the lungs compared to respective groups not challenged with E. coli LPS. The levels of TNF-α in the lungs did not differ among any of the groups. Control rats without E. coli LPS challenge showed higher levels of TGF-β2 compared to controls challenged with E. coli LPS.

Conclusion

These results show that lungs of rats exposed to pig barn air retain the ability to respond to E. coli LPS challenge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Swine production is a major agricultural industry in Canada and employs many fulltime workers who may work in shifts of 8 hours/day and 5 days/week inside the confined barns (reviewed in [1]). Full-time barn workers experience multiple-interrupted exposures to complex swine barn environment [2–5]. Swine barn environment is a heterogeneous mixture containing organic dust, various microbes, endotoxin and a number of gases such as ammonia, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulphide and methane [2, 6, 7]. Therefore, despite clean appearance, the modern large scale barns pose greater health risk to swine barn workers [8].

Exposure to barn air causes respiratory symptoms, loss of lung function, increased airway hyperresponsivneess (AHR) and airway inflammation (reviewed in [1]). Single (2–5 hour) experimental exposure of naïve human volunteers to barn environment induces fever, malaise, drowsiness [9], bronchial responsiveness [10] and lung inflammation with increased influx of neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils and macrophages in broncholavelolar lavage fluid (BALF) as well as chemoattractants such as IL-8 [8, 9, 11]. When compared to naïve volunteers, repeatedly exposed swine farmers demonstrate accentuated inflammatory and airway responses following a single experimental barn exposure [9, 12, 13] to indicate a possible adaptation response.

Recently, we have used rat and mouse models to mimic occupational exposures of full-time barn workers and demonstrate that single or five exposures to the barn air induce lung inflammation and AHR. Interestingly, the responses were attenuated after 20 exposures to the barn [14, 15]. We have also reported that barn air induced lung inflammation but not AHR is dependent on TLR4 activation [15]. Recently, we showed transient recruitment of pulmonary intravascular monocytes/macrophages (PIMMs) in rats at 48 hours after a single 8-hour exposure to the barn air and that treatment of these rats with Escherichia coli LPS (E. coli LPS) at 48 hours after the barn exposure resulted in robust lung inflammation [16]. Taken together, these data showed that single exposure to barn air induced recruitment of PIMMs and recruited PIMMs may mediate exacerbation of lung inflammation in response to a secondary challenge with E. coli LPS.

To date, we do not know lung responses of barn exposed animals to secondary challenge with LPS prior to PIMM recruitment. Because there is potential that a barn worker may be exposed to a bacterial infection within a few hours of finishing a work shift, it is important to understand this lung response. Since our previous work has shown significant recruitment of PIMMs at 48 hours post-single barn exposure [16], it is important to understand the host response to a secondary LPS challenge prior to this time point.

Therefore, in the current study, we used a recently characterized rat model of barn air induced lung inflammation to test a hypothesis that lungs of rats exposed to single or multiple times to pig barn air will be competent to respond to a E. coli LPS challenge at 18 hour post barn exposure. Our data show that lungs of rats exposed to the barn air remain capable of mounting an effective innate inflammatory response to a secondary E. coli LPS challenge.

Materials and methods

Rats and treatment groups

The animal experiment protocols were approved by Animal Research Ethics Board, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada and were conducted according to the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines. Specific pathogen-free, six-week-old, male, Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Canada) were maintained in the animal care unit of Western College of Veterinary Medicine. Rats were randomly assigned to six groups (n = 6 each). All the personnel involved in collection and analyses of samples were blinded to the treatment groups.

Exposure to swine barn air and E. coli LPS challenge

The barn exposure procedure has been described previously [14]. Briefly, the rats were placed in the cages and the cages were hung from the barn ceiling approximately at a height of two meters from the floor. Rats were exposed either to ambient air (N = 12) or to the barn air (N = 24). Barn exposure was for a period of eight hours per day for one (N = 12) or five days (N = 12). Immediately following exposure to the barn or ambient air, one half of these rats (n = 6/group) were euthanized and lung tissues were collected. The remaining half of the rats received a secondary challenge with E. coli LPS intravenously (1.5 μg/kg of body weight, Sigma-Aldrich, MD) 18 hours after completion of the barn exposure, observed for six-hours and then euthanized prior to collection of lung tissues for histology, immunohistochemistry and ELISA. Previously, we demonstrated induction of lung inflammation following intravenous administration of E. coli LPS (1.5 μg/kg) [16, 17].

Tissue collection and processing

Lung tissues were collected and processed as described previously [14, 17]. Briefly, following euthanasia, three pieces from each lung lobe (left and right) were taken and fixed in 4% buffered-paraformaldehyde for 16–18 hours and embedded in paraffin. Haematoxylin and eosin stained, five micron thick sections, were used for histopathological evaluation of lung inflammation. Remaining lung tissue was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until used.

Semi-quantitative evaluation of lung inflammation was performed as described before [15]. Briefly, histological signs of lung inflammation, such as perivascular and peribronchiolar inflammation as well as perivascular edema, were evaluated by an observer blinded to the study design. Stained slides were coded and randomly selected fields (40 × objective covering an area of 0.096 mm2/field) were used for subjective grading of histological changes. Absence of inflammation and edema was recorded as, "-", minimal inflammation as, "+", moderate as, "+ +", intense as, "+ + +" and very intense as, "+ + + +". When intensity of inflammation was intermediate between two successive grades such as "-"and "+", a range, "- to +" was assigned.

Immunohistochemistry

Lung sections were processed for immunohistochemistry as described [18]. Briefly, the sections were deparaffinized, hydrated and incubated with 5% hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase, treated with pepsin (2 mg/ml in 0.01 N HCl) for 45 minutes to unmask the antigens and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 30 minutes. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies against TNF-α(1:50), IL-1β(1:25), TGF-β2 (1:100) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., CA), ED-1 (1:150, mouse anti rat CD68, AbD Serotec, NC) and anti-granulocytes (1:50, BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON, Canada) followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated respective secondary antibodies (1:150; DAKO A/S, Denmark). The reaction was visualized using a colour development kit (VECTOR -VIP, Vector laboratories, USA). Controls consisted of staining without primary antibody or with isotype matched immunoglobulin instead of primary antibody.

We used ED-1 and anti-granulocyte antibodies to detect and quantify septal macrophages and granulocytes in the lungs respectively. Previously, ED-1 antibody has been shown to recognize a lysosomal protein in rat monocytes/macrophages [19, 20], while anti-granulocyte antibody recognizes all types of granulocytes [21] and has previously been used by our group [16]. Following immunohistochemistry, stained slides (n = 3/group) were coded and twenty randomly selected fields (High Power Field (HPF) covered by 40 × objective) were used for counting ED-1 and anti-granulocyte positive cells in the lung septae.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

We followed sandwich ELISA protocols to measure the concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β and TGF-β2 using commercially available capture/detection antibody pairs and recombinant protein standards (TNF-α, BD Biosciences, ON, Canada and IL-1β and TGF-β2, R&D Systems, MN, USA) as described before [15, 17, 22]. Briefly, lung samples were homogenized in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (100 mg lung tissue/ml of HBSS) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (100 μl/10 ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). ELISA plates were coated with capture antibody (over night at 4°C), blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma Aldrich, Canada) followed by addition of standards and samples (n = 3,100 μl each in duplicates) and incubation over night at 4°C. The plates were washed with PBS-Tween and incubated with detection antibody (60 minutes at 37°C) followed by color detection reagents and reading at 450 nm.

Statistical analyses

All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Group differences were examined for significance using two-way analysis of variance with Tukey Test as post hoc test (SigmaStat for Windows Version 3.11, San Jose, CA). Significance was established at P < 0.05.

Results

Histopathology of lung sections

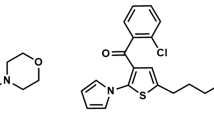

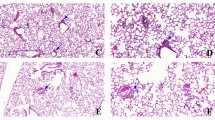

Semi quantitative evaluation of histological signs of lung inflammation is summarized in Table 1. Control rat lungs showed no signs of inflammation (Figure 1A) while rats treated with intravenous E. coli LPS alone and one or five day barn exposed rats with or without E. coli LPS treatment showed lung inflammation characterized by peribrochiolar infiltration of neutrophils (Figure 1B), perivascular and peribrochiolar infiltration of inflammatory cells (Figure 1C–F) and perivascular edema (picture not shown).

Histopathology of lung sections. Histopathological changes in the lungs of rats exposed either to ambient (control) or swine barn air with or without E. coli LPS challenge were evaluated using hematoxylin and eosin stained sections. Control rat lung tissues showed no inflammation and normal architecture of the organ (A) while rats challenged with E. coli LPS (B), one day barn exposed rats without E. coli LPS (C) and with E. coli LPS (D), five day barn exposed rats with or without E. coli LPS (E and F respectively) showed peribronchiolar (arrows and inset, B) and septal neutophilic infiltration (arrows and inset, C), perivascular infiltration of leukocytes (arrowheads and insets, C-E), and peribronchiolar accumulation of leukocytes (arrowhead and inset, F). Original magnification A-B: ×400, C-F: ×100 and micrometer bar = 50 μm.

Immunohistochemistical identification and quantification of macrophages and granulocytes

There was no significant difference in the mean number of ED-1 positive cells in the lung septae among all the groups (Figure 2F, P > 0.05). The mean number of granulocytes was increased in the lung septae of one (P = 0.029) or five (P = 0.051) day exposed rats challenged with E. coli LPS when compared to one or five day exposed rats not treated with the LPS (Figure 3F).

Immunohistochemical quantification of monocytes/macrophages in the lung. Monocytes/macrophages were stained using ED-1 antibody in the lung sections from control (A), E. coli LPS (B), one day barn exposed rats without and with E. coli LPS challenge (C-D) and five day barn exposed rats without (E) (arrows) and with E. coli LPS challenge respectively (picture not shown) F: Quantification of septal monocytes/macrophages revealed no significant difference among any of the groups (P > 0.05).Original magnification A-F: ×400 and micrometer bar = 50 μm.

Immunohistochemical quantification of granulocytes in the lung. Granulocytes in the lung sections were stained using anti-granulocyte antibody from control (A, arrows and inset), E. coli LPS (B), one day (C-D) exposed rats without and with E. coli LPS challenge and five day (E) barn exposed rats without (arrows, B-E) and with E. coli LPS challenge (picture not shown) respectively. F: Quantification of septal granulocytes showed increased numbers in one day exposed rats with E. coli LPS challenge compared to one day exposed rats without E. coli LPS challenge (P = 0.029). Five day exposed rats with E. coli LPS challenge show a trend towards significant increase when compared to respective five day exposed rats without E. coli LPS challenge (F, P = 0.051). Original magnification A-F: ×400 and micrometer bar = 50 μm.

Expression and quantification of IL-1β

Immunohistochemistry detected staining for IL-1β in airway epithelium (Figure 4, A–E), blood vessel wall, lung septa and occasionally in alveolar macrophages (AMs) (data not shown). Quantification with ELISA revealed significantly higher IL-1β concentrations in the lungs of ambient air or barn exposed rats (one or five exposures) that received E. coli LPS challenge compared to respective groups without E. coli LPS challenge (Figure 4F, P < 0.001).

IL-1β expression and quantification in the lung. Immunohistochemical expression of IL-1β was detected using anti-IL-1β antibody in the lung sections from controls (A-B), one day (C-D) exposed rats without and with E. coli LPS challenge respectively, five day exposed rats without E. coli LPS challenge (E) and with E. coli LPS challenge (picture not shown). IL-1β expession in the airway epithelium (arrows, A-E) is shown. F. Quantification of IL-1β protein using ELISA shows increased concentrations in rats that received E. coli LPS compared to respective groups of rats that did not receive E. coli LPS (Figure 4, P < 0.001). Original magnification A-F: ×400 and micrometer bar = 50 μm.

Expression and quantification of TNF-α

Immunohistochemistry detected TNF-α in airway epithelium (Figure 5A–E), blood vessel wall, lung septa and occasionally in AMs and quantification using ELISA revealed no difference among any of the groups (Figure 5F, P > 0.05).

TNF-α expression and quantification in the lung. Immunohistochemical expression of TNF-α was detected using anti-TNF-α antibody in the lung sections from controls (A-B), one day (C-D) exposed rats without and with E. coli LPS challenge respectively, five day exposed rats without E. coli LPS challenge (E) and with E. coli LPS challenge (picture not shown). TNF-α expression in the airway epithelium (arrows, A-E) is shown. F. Quantification of TNF-α protein using ELISA showed no significant difference among any of the groups (Figure 5, P > 0.05). Original magnification A-F: ×400 and micrometer bar = 50 μm.

Expression and quantification of TGF-β2

Immunohistochemistry detected TGF-β2 in airway epithelium (Figure 6A–E), blood vessel wall, lung septa and occasionally in AMs and quantification using ELISA revealed that control rats without E. coli LPS challenge showed higher levels of TGF-β2 compared to controls rats challenged with E. coli LPS (Figure 6F, P = 0.001).

TGF-β2 expression and quantification in the lung. Immunohistochemical expression of TGF-β2 was detected using anti- TGF-β2 antibody in the lung sections from controls (A-B), one day (C-D) exposed rats without and with E. coli LPS challenge respectively, five day exposed rats without E. coli LPS challenge (E) and with E. coli LPS challenge (picture not shown). TGF-β2 expression in the airway epithelium (arrows, A-E) is shown. F. Quantification of TGF-β2 protein using ELISA showed increased levels in control rats without E. coli LPS challenge compared to control rats with E. coli LPS challenge (*, P = 0.001).Original magnification A-F: ×400 and micrometer bar = 50 μm.

Discussion

We conducted this study to investigate lung responses to a secondary LPS challenge in rats exposed to barn air. Our data show that lungs of rats exposed to barn air became more inflamed following challenge with LPS when compared to those exposed to barn air only. These data suggest that lungs of animals exposed to pig barn air are capable of responding to microbial challenges.

We have previously demonstrated that significant PIMM recruitment is observed at 48 hours after a single exposure to pig barn air and these recruited PIMMs exacerbated lung inflammation in response to a secondary LPS challenge [16]. Now, we studied secondary LPS-induced lung inflammation in rats exposed to the barn air prior to PIMM recruitment. We chose to do an E. coli LPS challenge at 18 hours after single or five day barn exposure and confirmed the lack of significant recruitment of PIMMs at these time points by immunohistochemical staining using ED-1 antibody which is a known marker for rat monocytes/macrophages.

In the current study we have demonstrated induction of lung inflammation following one or five days of barn exposure as before [14–16]. The E. coli LPS challenge of one day barn exposed but not control rats at 18 hour post-exposure showed an increase in granulocyte recruitment compared to respective control groups. However, there were no differences in granulocyte numbers between LPS-treated barn exposed and control animals. Neutrophils are the predominant granulocytes recruited into the inflamed lung [23] and are considered central to development of acute lung inflammation [24, 25]. As expected we did not observe an increase in lung monocyte/macrophage numbers at 6 hour post-LPS challenge, as this early time point in acute lung inflammation is characterized by an early recruitment of neutrophils followed by monocytes and macrophages in the later periods [26, 27]. However, our previous work in rat endotoxin-induced lung inflammation model has also shown increased monocytes recruitment at 3 and 24 hour time points, both dependent on neutrophils [28]. Our current data show that lungs of animals, that had been exposed to barn air, experienced an inflammatory response following challenge with LPS that was equal to, if not greater than that experienced by animal lungs that had not been exposed to barn air prior to LPS challenge. Endotoxin or LPS in the barn or intravenously administered LPS alone used in this study will likely induce different host responses. Intravenously administered LPS very likely induce systemic vascular activation including lung vascular inflammation and exacerbate lung inflammation [16, 17]. In contrast to this, LPS in the barn air is associated with other contaminants in the barn and primarily induces lung inflammation and associated respiratory symptoms [1]. Some of the differences in the host responses following intravenous LPS challenge or the barn exposure may be due to differences in dose/exposure, duration of exposure and presence of other agents in the barn will all account for differences in host responses.

Barn exposed as well as control rats challenged with LPS showed increased concentrations of IL-1β but not TNF-α in lung homogenates compared to their respective controls. Again, there were no differences in IL-1β or TNF-α expression between barn exposed and control rats challenged with LPS. IL-1β is produced by monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils as well as endothelial cells and fibroblasts, and is a known early response cytokine in acute lung inflammation and induces expression of adhesion molecules to regulate neutrophil migration [29–33]. IL-1β also directly activates neutrophils through stimulation of mitogen activated protein kinases to result in increased superoxide anion production and respiratory burst in neutrophils [34, 35]. IL-1β also induces fever, increases vascular permeability, production of IL-6 and leukocyte adherence to endothelium [36, 37]. On the other hand, neutralization of IL-1β has proven protective and beneficial to the host [38]. Based on the expression of these two proinflammatory cytokines, it appears that single or multiple exposures to barn air do not dampen the inflammatory response of lungs to LPS challenge.

Because lung inflammation is controlled by a complex network of both pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines [39], we examined the tissue expression and quantification of TGF-β2, a known anti-inflammatory cytokine with important roles in tissue repair and remodeling [40, 41]. The data show reduced expression of TGF-β2 in LPS challenged control rats compared to control rats without E. coli LPS challenge. This observation indicates that the suppression of TGF-β2 in inflamed lungs may be due to an active inflammatory reaction which is similar to previous reports of suppression of TGF-β2 expression in lungs of LPS challenged rats [42]. We have reported similar data from rats challenged with E. coli LPS at 48 hours after single barn exposure which contain significant numbers of PIMMs [16]. In contrast to LPS challenge 48 hours after an exposure to barn air or of control rats, we did not observe any change in the expression of TGF-β2 when rats were challenged with LPS at 18 hours after one or five exposures to barn air. It seems that exposure to barn air may have suppressed expression of TGF-β2 to LPS challenge. Considering well established roles of TGF-β2 in lung injury and repair, it may be useful to undertake further studies to explore the role of this cytokine in lung inflammation and repair following exposure to the barn air. Furthermore, because of the involvement of TLR4, it may also be useful to conduct in vitro studies to clarify the cell signaling pathways activated by the barn air.

Conclusion

Our data show that exposure to swine barn environment for one or five days induces lung inflammation, while a secondary challenge with E. coli LPS exacerbates the lung inflammation in rats exposed to pig barn air. These data suggest that exposure to barn air does not suppress lung's ability to respond to a secondary LPS challenge.

References

Charavaryamath C, Singh B: Pulmonary effects of exposure to pig barn air. J Occup Med Toxicol 2006, 1: 10. 10.1186/1745-6673-1-10

Donham KJ, Popendorf W, Palmgren U, Larsson L: Characterization of dusts collected from swine confinement buildings. Am J Ind Med 1986, 10: 294–297. 10.1002/ajim.4700100318

Cole D, Todd L, Wing S: Concentrated swine feeding operations and public health: a review of occupational and community health effects. Environ Health Perspect 2000, 108: 685–699. 10.2307/3434721

Wenger I: Air Quality and Health of Career Pig Barn Workers. Advances in Pork Production 1999, 10: 93–101.

Wenger II, Ouellette CA, Feddes JJ, Hrudey SE: The design and use of the Personal Environmental Sampling Backpack (PESB II) for activity-specific exposure monitoring of career pig barn workers. J Agric Saf Health 2005, 11: 315–324.

Asmar S, Pickrell JA, Oehme FW: Pulmonary diseases caused by airborne contaminants in swine confinement buildings. Vet Hum Toxicol 2001, 43: 48–53.

Donham KJ, Popendorf WJ: Ambient levels of selected gases inside swine confinement buildings. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 1985, 46: 658–661.

Cormier Y, Israel-Assayag E, Racine G, Duchaine C: Farming practices and the respiratory health risks of swine confinement buildings. Eur Respir J 2000, 15: 560–565. 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15.22.x

Larsson K, Eklund AG, Hansson LO, Isaksson BM, Malmberg PO: Swine dust causes intense airways inflammation in healthy subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994, 150: 973–977.

Malmberg P, Larsson K: Acute exposure to swine dust causes bronchial hyperresponsiveness in healthy subjects. Eur Respir J 1993, 6: 400–404.

Larsson BM, Palmberg L, Malmberg PO, Larsson K: Effects of exposure to swine dust on levels of IL-8 in airway lavage fluid. Thorax 1997, 52: 638–642.

Palmberg L, Larssson BM, Malmberg P, Larsson K: Airway responses of healthy farmers and nonfarmers to exposure in a swine confinement building. Scand J Work Environ Health 2002, 28: 256–263.

Israel-Assayag E, Cormier Y: Adaptation to organic dust exposure: a potential role of l-selectin shedding? Eur Respir J 2002, 19: 833–837. 10.1183/09031936.02.02182001

Charavaryamath C, Janardhan KS, Townsend HG, Willson P, Singh B: Multiple exposures to swine barn air induce lung inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness. Respir Res 2005, 6: 50. 10.1186/1465-9921-6-50

Charavaryamath C, Juneau V, Suri SS, Janardhan KS, Townsend H, Singh B: Role of toll-like receptor 4 in lung inflammation following exposure to Swine barn air. Exp Lung Res 2008, 34: 19–35. 10.1080/01902140701807779

Gamage LN, Charavaryamath C, Swift TL, Singh B: Lung inflammation following a single exposure to swine barn air. J Occup Med Toxicol 2007, 2: 18. 10.1186/1745-6673-2-18

Charavaryamath C, Janardhan KS, Caldwell S, Singh B: Pulmonary intravascular monocytes/macrophages in a rat model of sepsis. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 2006, 288: 1259–1271. 10.1002/ar.a.20401

Singh B, Rawlings N, Kaur A: Expression of integrin αvβ3 in pig, dog and cattle. Histol Histopathol 2001,16(4):1037–1046.

Dijkstra CD, Dopp EA, Joling P, Kraal G: The heterogeneity of mononuclear phagocytes in lymphoid organs: distinct macrophage subpopulations in rat recognized by monoclonal antibodies ED1, ED2 and ED3. Adv Exp Med Biol 1985, 186: 409–419.

Damoiseaux JG, Dopp EA, Calame W, Chao D, MacPherson GG, Dijkstra CD: Rat macrophage lysosomal membrane antigen recognized by monoclonal antibody ED1. Immunology 1994, 83: 140–147.

van Goor H, Fidler V, Weening JJ, Grond J: Determinants of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis in the rat after renal ablation. Evidence for involvement of macrophages and lipids. Lab Invest 1991, 64: 754–765.

Gordon JR, Zhang X, Stevenson K, Cosford K: Thrombin induces IL-6 but not TNFalpha secretion by mouse mast cells: threshold-level thrombin receptor and very low level FcepsilonRI signaling synergistically enhance IL-6 secretion. Cell Immunol 2000, 205: 128–135. 10.1006/cimm.2000.1714

Thorn J: The inflammatory response in humans after inhalation of bacterial endotoxin: a review. Inflamm Res 2001, 50: 254–261. 10.1007/s000110050751

Kinoshita M, Ono S, Mochizuki H: Neutrophils mediate acute lung injury in rabbits: role of neutrophil elastase. Eur Surg Res 2000, 32: 337–346. 10.1159/000052215

Abraham E: Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2003, 31: S195-S199. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8

Larsen GL, Holt PG: The concept of airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162: S2-S6.

Kaplanski G, Marin V, Montero-Julian F, Mantovani A, Farnarier C: IL-6: a regulator of the transition from neutrophil to monocyte recruitment during inflammation. Trends Immunol 2003, 24: 25–29. 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)00013-3

Janardhan KS, Sandhu SK, Singh B: Neutrophil depletion inhibits early and late monocyte/macrophage increase in lung inflammation. Front Biosci 2006, 11: 1569–1576. 10.2741/1904

Dinarello CA: Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest 2000, 118: 503–508. 10.1378/chest.118.2.503

Kasama T, Miwa Y, Isozaki T, Odai T, Adachi M, Kunkel SL: Neutrophil-derived cytokines: potential therapeutic targets in inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2005, 4: 273–279. 10.2174/1568010054022114

Tosi MF: Innate immune responses to infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005, 116: 241–249. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.036

Williams JH Jr, Patel SK, Hatakeyama D, Arian R, Guo K, Hickey TJ, et al.: Activated pulmonary vascular neutrophils as early mediators of endotoxin-induced lung inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1993, 8: 134–144.

Parsey MV, Tuder RM, Abraham E: Neutrophils Are Major Contributors to Intraparenchymal Lung IL-1{beta} Expression After Hemorrhage and Endotoxemia. J Immunol 1998, 160: 1007–1013.

Yagisawa M, Yuo A, Kitagawa S, Yazaki Y, Togawa A, Takaku F: Stimulation and priming of human neutrophils by IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta: complete inhibition by IL-1 receptor antagonist and no interaction with other cytokines. Exp Hematol 1995, 23: 603–608.

Suzuki K, Hino M, Kutsuna H, Hato F, Sakamoto C, Takahashi T, et al.: Selective Activation of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascade in Human Neutrophils Stimulated by IL-1{beta}. J Immunol 2001, 167: 5940–5947.

Strieter RM, Belperio JA, Keane MP: Cytokines in innate host defense in the lung. J Clin Invest 2002, 109: 699–705.

Feghali CA, Wright TM: Cytokines in acute and chronic inflammation. Front Biosci 1997, 2: d12-d26.

Standiford TJ: Anti-inflammatory cytokines and cytokine antagonists. Curr Pharm Des 2000, 6: 633–649. 10.2174/1381612003400533

Thacker EL: Lung inflammatory responses. Vet Res 2006, 37: 469–486. 10.1051/vetres:2006011

Letterio JJ, Roberts AB: TGF-beta: a critical modulator of immune cell function. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1997, 84: 244–250. 10.1006/clin.1997.4409

Bartram U, Speer CP: The role of transforming growth factor beta in lung development and disease. Chest 2004, 125: 754–765. 10.1378/chest.125.2.754

Ayache N, Boumediene K, Mathy-Hartert M, Reginster JY, Henrotin Y, Pujol JP: Expression of TGF-betas and their receptors is differentially modulated by reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide in human articular chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2002, 10: 344–352. 10.1053/joca.2001.0499

Acknowledgements

The work was supported through a grant from Lung Association of Saskatchewan to Dr. B. Singh. Dr. C. Charavaryamath is a recipient of a Graduate Merit Scholarship from College of Graduate Studies and Research, Founding Chairs Graduate Fellowship from Canadian Centre for Health and Safety in Agriculture, University of Saskatchewan and a scholarship from the CIHR Strategic Training Program in Public Health and the Agricultural Rural Ecosystem and Partner Institutes including the Institute of Cancer Research, Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, Institute of Infection and Immunity, Institute of Population and Public Health and the University of Saskatchewan. Taryn Keet was a recipient of an Undergraduate Summer Research Award from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Gurpreet K. Aulakh is a recipient of Graduate Teaching Fellowship from the Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences, University of Saskatchewan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CC carried out the experiment, did the histopathological evaluation, statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. TK did the immunohistochemistry and GKA participated in the quantification of immunohistochemistry data. HT participated in statistical analyses and manuscript preparation. BS conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination as well as manuscript preparation. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Charavaryamath, C., Keet, T., Aulakh, G.K. et al. Lung responses to secondary endotoxin challenge in rats exposed to pig barn air. J Occup Med Toxicol 3, 24 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-3-24

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-3-24