Abstract

Background

Low levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL) are considered an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and constitute one of the criteria for the Metabolic Syndrome (MetS). Lifestyle interventions promoting a low-fat, plant-based eating pattern appear to paradoxically reduce cardiovascular risk but also HDL levels. This study examined the changes in MetS risk factors, in particular HDL, in a large cohort participating in a 30-day lifestyle intervention that promoted a low-fat, plant-based eating pattern.

Methods

Individuals (n = 5,046; mean age = 57.3 ± 12.9 years; 33.5% men, 66.5% women) participating in a in a Complete Health Improvement Program (CHIP) lifestyle intervention within the United States were assessed at baseline and 30 days for changes in body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), lipid profile and fasting plasma glucose (FPG).

Results

HDL levels decreased by 8.7% (p<0.001) despite significant reductions (p<0.001) in BMI (-3.2%), systolic BP (-5.2%), diastolic BP (-5.2%), triglycerides (TG; -7.7%), FPG (-6.3%), LDL (-13.0%), total cholesterol (TC, -11.1%), TC: HDL ratio (-3.2%), and LDL: HDL ratio (-5.3%). While 323 participants classified as having MetS at program entry no longer had this status after the 30 days, 112 participants acquired the MetS classification as a result of reduction in their HDL levels.

Conclusions

When people move towards a low-fat, plant-based diet, HDL levels decrease while other indicators of cardiovascular risk improve. This observation raises questions regarding the value of using HDL levels as a predictor of cardiovascular risk in populations who do not consume a typical western diet. As HDL is part of the assemblage of risk factors that constitute MetS, classifying individuals with MetS may not be appropriate in clinical practice or research when applying lifestyle interventions that promote a plant-based eating pattern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epidemiological studies indicate that low levels of plasma or serum HDL is an important risk factor in the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. Consequentially, the National Cholesterol Education Program has advocated increasing HDL levels as an important strategy for the primary prevention of CVD [2]. Lowered HDL has also been included as one of the risk factors used to establish a diagnosis of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) [3].

Lifestyle interventions that promote a low-fat, plant-based eating pattern have been shown to reduce HDL levels [4–8]. Consequentially, it has been suggested that low-fat, plant-based diets may not be ideal for people suffering CVD [9, 10], despite being well established to reduce other CVD risk factors including body mass, BP, TC and LDL [4–8]. Furthermore, long-term intervention studies involving low-fat, plant-based diets have even been shown to regress atherosclerotic plaques [4, 7] and reduce cardiac events [4], despite also lowering HDL levels. This apparently conflicting observation has led to debate surrounding the merits of a low-fat, plant-based diet for the management of CVD. In a recent review of HDL [11] argued that lowered HDL level is not associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease in the absence of other lipid or non-lipid risk factors.

The purpose of this study was to further explore the changes in CVD risk factors, especially HDL, in a large cohort of individuals participating in a lifestyle intervention that advocated a low-fat, plant-based eating pattern—the Complete Health Improvement Program (CHIP). The effect of these changes on the MetS rubic and the implications of this for classifying individuals with MetS were specifically examined.

Methods

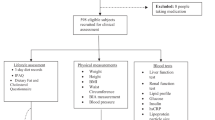

The study evaluated the pre- to post-biometric changes of 5,046 individuals (mean age = 57.3±12.9 years; 33.5% men, 66.5% women), who self-selected to participate in a CHIP lifestyle intervention conducted in various locations throughout the United States. Consent for the study was obtained from Avondale College of Higher Education Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. 20:10:07).

The CHIP intervention, previously described [5, 6, 12], encouraged and supported participants to move towards a low-fat, plant-based diet ad libitum, with emphasis on the whole-food consumption of grains, legumes, fruits and vegetables. Specifically, the program recommended less than 20% of calories be derived from fat. In addition, participants were encouraged to consume 2-2.5 litres of water daily and limit their daily intake of added sugar, sodium and cholesterol to 40 g, 2,000 mg, and 50 mg respectively. Furthermore, the program encouraged participants to engage in 30 minutes of daily moderate-intensity physical activity and practice stress management techniques.

Before participating in the CHIP intervention (baseline) and then again at 30 days (post-intervention), participants’ height, weight, and BP were taken. In addition, fasting (12-hour) blood samples were collected by trained phlebotomists and analysed for TC, LDL, HDL, TG and FPG levels.

The five risk factors for MetS, as described by the "harmonized definition" [3] are: central obesity (based on population specific waist circumference), raised BP (systolic ≥130 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥ 85 mmHg), elevated FPG (≥5.5 mmol/L), increased TG (≥1.7 mmol/L), and decreased HDL (<1.03 mmol/L in males and <1.3 mmol/L in females). The study participants were classified as meeting these criteria at baseline and post-intervention, however, as waist circumference was not measured in this study, BMI >30 kg/m2 was used as surrogate for central obesity, as suggested by the International Diabetes Federation [13]. Participants were deemed as having MetS if they met three or more of the defining criteria [3].

The data were analysed using IBM™ Statistics (version 19) and expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The extent of changes (baseline to post-intervention) in the MetS risk factors were assessed using paired t-tests. McNemar chi square test was used to determine changes from baseline to post-intervention in the number of participants who met the five MetS risk factor criteria, as well as the number who were classified as having the syndrome.

Results

Overall changes

After 30 days, significant mean reductions (p<0.001) were recorded in all of the five MetS risk factors, including HDL, which decreased almost 9% (Table 1).

HDL

The change in HDL, stratified according to baseline HDL level, is presented in Table 2. Participants with the highest initial levels of HDL experienced the greatest decreases in the 30 days. The decrease in HDL was not as great as the decrease in LDL and TC (13% and 11%, respectively), resulting in improvements in the TC:HDL ratio of 3% and the LDL:HDL ratio of 5% (Table 1).

MetS

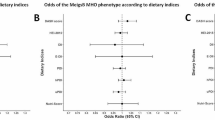

As shown in Table 3, there was a significant reduction in the number of participants who met the MetS criteria for BMI, BP, TG and FPG, but a significant increase in the number of participants who met the criteria for HDL.

While 1889 (41.7%) participants entered the program characterised as having MetS, this was reduced to 1566 (34.6%) following the intervention; a reduction of 323 participants. Two hundred and fifty seven participants who were not classified as having MetS at program entry acquired this status at the completion of the intervention, however, 157 of these individuals (61%) only did so because of reduced HDL levels. For these individuals, the TC: HDL and LDL: HDL ratios increased significantly from baseline to post-intervention (3.56±0.77 versus 4.12±0.87, p<0.001; 2.31±0.71 versus 2.44±0.76, p=0.006, respectively) as both TC (12%, p<0.001) and LDL (15%, p<0.001) did not decrease as much as HDL (21%, p<0.001).

Discussion

The most striking observation of the present study is that when people move towards a low-fat, plant-based diet, HDL levels tend to decrease while all other measures of cardiovascular risk improve. This large study is the first to highlight the implications of this effect for MetS classification. Furthermore, the findings raise questions about the usefulness of measuring HDL levels for predicting cardiovascular risk, especially among specific groups such as vegetarian populations.

Further evidence that the cardiovascular risk of the participants in this study improved despite the trend for HDL to decrease, is seen in the improvements in the overall TC: HDL and LDL: HDL ratios. A meta-analysis of 61 prospective studies with vascular deaths as an endpoint suggested that the TC: HDL ratio was more predictive than either HDL or non-HDL cholesterol sub-fractions, and two times more predictive than TC [14]. However, in the present study, this ratio, as well as the ratio of LDL: HDL, significantly increased among participants who were newly characterised with MetS and low HDL levels. In addition, there were significant reductions in the number of participants who met the MetS criteria for BMI, BP, TG and FPG levels (11-29%), as compared to the 30% increase in the number of participants who meet the HDL criterion. These results show that in the context of interventions that emphasise a low-fat, plant-based eating pattern, changes in HDL levels may be misleading, whether measured as an absolute value or calculated as a ratio of TC or LDL.

The consistently strong inverse association between low HDL levels and the risk of cardiovascular events observed in epidemiological studies [15, 16], has traditionally been explained by its role in reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), also known as cholesterol efflux [16]. Notwithstanding this role, HDL more recently has been shown to have many anti-atherogenic properties, which include anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, nitric oxide promoting, prostacyclin-stabilizing, and platelet-inhibiting functions [17, 18]. Indeed, it has been postulated that the anti-inflammatory properties of HDL and its ability to protect LDL from oxidation may be just as important as its role in RCT [19].

Despite the documented anti-atherogenic properties of HDL, there is evidence that questions the relationship between HDL levels and risk of cardiovascular events, as many individuals who suffer coronary atherosclerotic events have normal or even elevated HDL levels [18, 20]. Specifically, the Framingham study demonstrated that more than 40% of cardiac events occurred in men and women with normal HDL levels [20]. In addition, other studies have shown that when HDL levels are raised pharmacologically, the elevated levels do not always correlate with reduced risk of coronary heart disease [21, 22].

The result of this study, which suggests that HDL levels may not be helpful for predicting cardiovascular risk in individuals consuming a low-fat, plant-based diet, is supported by other epidemiological and clinical studies. Over 30 years ago, Connor observed that the Tarahumara Indians of Mexico, who consumed a largely plant-based diet comprising approximately 12% fat, 13% protein (predominantly from corn and beans) and 85% carbohydrate, had very low rates of vascular disease and blood lipids, including HDL [23]. However, blood lipids, including HDL, were observed to significantly increase after only five weeks when their traditional diet was changed to a Western diet [24]. It was argued that the increase in HDL was the "normal response to a high-fat diet" and that low-HDL in concert with low-LDL in a low-fat diet is associated with a low risk of coronary disease. Other epidemiological findings also show that individuals who consume a plant-based diet are at lower risk of CVD and type 2 diabetes mellitus, despite having lowered HDL levels [19, 25]. In addition, the Lifestyle Heart Trial [7], which incorporated a plant-based diet with less than 10% fat, showed a 7.9% improvement in measured coronary artery percent diameter stenosis after five years despite a 13% reduction in HDL. Similarly, individuals with diagnosed CVD and a recommendation for bypass surgery who participated in the Pritikin residential program, which recommends a plant-based diet (10% fat), experienced a 16% reduction in HDL but decreases in symptomatic angina [26]. These patients averted surgery for more than five years after program entry despite sustained lowered HDL levels.

The value of increasing HDL levels has been further questioned as its range of functions has become better understood [11, 17, 18]. With its heterogeneous structure and subtypes, varying functions are now being demonstrated [18]. To date, a number of apolipoproteins and antioxidant enzymes have been identified in the HDL structure that may explain its anti-inflammatory (e.g. ApoA-1 and paraoxonase 1) and inflammatory properties (e.g. ApoA-II and ApoC-III) [16, 18, 27]. Although the mechanisms governing HDL inflammatory and anti-inflammatory ratios are yet to be fully elucidated, these may at least in part be influenced by the presence of oxidized lipids and oxidants, which inhibit or directly damage the anti-inflammatory molecules on HDL [27]. Noteworthy, antioxidants and phytonutrients abundant in plant foods may increase the activity of HDL enzymes or counter the adverse effect of oxidants on apoA-1 and/or the pro-inflammatory effect on LDL lipids [28]. Given that people following a low-fat, plant-based diet typically have lowered levels of serum TC and LDL, the need for elevated HDL levels may be diminished from an RCT perspective. Indeed, lifestyle factors have been shown to influence the subpopulations of HDL.

Additional evidence against the role of HDL in CVD risk has come from genetic studies, designed to examine the associations of LDL, HDL and TG with CVD risk [29, 30]. Early studies showed that rare mutations that encode LCAT (lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase) and ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette transporter, also known as cholesterol efflux regulatory protein (CERP)), which profoundly reduce HDL levels, were inconsistently associated with CVD risk [29]. Subsequent Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses examined several DNA variants that affect HDL levels and found no associations with major adverse CVD end points and risk of myocardial infarction [29]. In contrast, genetics variants that raise LDL levels significantly increased CVD risk. More recent MR analyses, using carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a surrogate for atherosclerosis, confirmed a strong relationship between LDL and CIMT, but not with HDL and TG [30].

There is also growing evidence that lifestyle interventions may be able to modulate the inflammatory or anti-inflammatory properties of HDL. In patients at risk of CVD, the anti-inflammatory properties of HDL improved following lifestyle modification, despite reductions in HDL [28]. In another study, the HDL shifted from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory in obese men, with MetS, who underwent a three-week intervention involving a low-fat, high- fibre diet and exercise [19]. More specifically, consumption of saturated fat reduces the anti-inflammatory potential of HDL, but consumption of polyunsaturated fat has been shown to increase it [31]. The regulation and function of HDL appears more complex than originally thought-- although high HDL levels are associated with reduced CVD at a population level, at an individual level HDL function may be more important than the actual HDL levels[32].

Conclusion

The findings of this study question the value of using HDL levels as a predictor of cardiovascular risk, especially in populations who do not consume a typical Western diet. The appropriateness of applying standard HDL criteria to populations that consume a plant-based diet may be particularly problematic. Finally, characterising individuals with MetS may not be appropriate in clinical practice or research when applying lifestyle interventions that promote a plant-based eating pattern.

Abbreviations

- MetS:

-

Metabolic Syndrome

- CHIP:

-

Complete Health Improvement Program

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- Apo:

-

Apolipoprotein

- LCAT:

-

LECITHIN cholesterol acyl transferase

- ABCA1:

-

ATP-binding cassette transporter.

References

Gordon DJ, Rifkind BM: High-density lipoprotein–the clinical implications of recent studies. N Engl J Med. 1989, 321 (19): 1311-1316. 10.1056/NEJM198911093211907.

Expert Panel on Detection Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults: Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA. 2001, 285: 2486-2497. 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486.

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart J, James WPT, Loria CM, Smith SC: Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009, 120 (16): 1640-1645. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644.

Esselstyn CB, Ellis SG, Medendorp SV, Crowe TD: A strategy to arrest and reverse coronary artery disease: a 5-year longitudinal study of a single physician’s practice. J Fam Pract. 1995, 41: 560-568.

Rankin P, Morton DP, Diehl H, Gobble J, Morey P, Chang E: Effectiveness of a volunteer-delivered lifestyle modification program for reducing cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am J Cardiol. 2012, 109: 82-86. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.069.

Morton DP, Rankin P, Morey P, Kent L, Hurlow T, Chang E, Diehl H: The effectiveness of the complete health improvement program (CHIP) in Australasia for reducing selected chronic disease risk factors: a feasibility study. N Z Med J. 2013, 126: 43-54.

Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, Brown SE, Gould KL, Merritt TA, Sparler S, Armstrong WT, Ports TA, Kirkeeide RL, Hogeboom C, Brand RJ: Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998, 280: 2001-2007. 10.1001/jama.280.23.2001.

Barnard RJ: Effects of life-style modification on serum lipids. Arch Intern Med. 1991, 151: 1389-1394. 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400070141019.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Spertus JA, Costa F: Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American heart association/national heart, lung, and blood institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005, 112: 2735-2752. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404.

National Cholesterol Education Program: Third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002, 106: 3143-3421.

Despres JP: HDL cholesterol studies–more of the same?. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013, 10: 70-72. 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.182.

Morton DP: The complete health improvement program (CHIP) as a lifestyle intervention for the prevention, management and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Manage J. 2012, 41: 26-27.

Alberti K, Zimmet P, Shaw J: Metabolic syndrome—a new world‒wide definition. A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diab Med. 2006, 23: 469-480. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x.

Prospective Studies Collaboration: Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet. 2007, 370: 1829-1839.

Brinton EA, Eisenberg S, Breslow JL: A low-fat diet decreases high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels by decreasing HDL apolipoprotein transport rates. J Clin Invest. 1990, 85: 144-151. 10.1172/JCI114405.

Rader DJ: Molecular regulation of HDL metabolism and function: implications for novel therapies. J Clin Invest. 2006, 116: 3090-3100. 10.1172/JCI30163.

Leite JO, Fernandez ML: Should we take high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels at face value?. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010, 10: 1-3.

Jensen MK, Rimm EB, Furtado JD, Sacks FM: Apolipoprotein C-III as a potential modulator of the association between HDL-cholesterol and incident coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012, 1:

Roberts CK, Ng C, Hama S, Eliseo AJ, Barnard RJ: Effect of a short-term diet and exercise intervention on inflammatory/anti-inflammatory properties of HDL in overweight/obese men with cardiovascular risk factors. J Appl Physiol. 2006, 101: 1727-1732.

Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR: High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham study. Am J Med. 1977, 62: 707-714. 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9.

Briel M, Ferreira-Gonzalez I, You JJ, Karanicolas PJ, Akl EA, Wu P, Blechacz B, Bassler D, WEi X, Sharman A, Whitt I, Da Siva SA, Khalid Z, Normann A, Zhou Q, Walter SD, Vale N, Bhatnagar N, O’Regan C, Mills WJ, Bucher HC, Montori VM, Guyatt GH: Association between change in high density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMJ. 2009, 338: b92-10.1136/bmj.b92.

Singh IM, Shishehbor MH, Ansell BJ: High-density lipoprotein as a therapeutic target: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007, 298: 786-798. 10.1001/jama.298.7.786.

Connor WE, Cerqueira MT, Connor RW, Wallace RB, Malinow MR, Casdorph HR: The plasma lipids, lipoproteins, and diet of the Tarahumara indians of Mexico. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978, 31: 1131-1142.

McMurry MP, Cerqueira MT, Connor SL, Connor WE: Changes in lipid and lipoprotein levels and body weight in Tarahumara Indians after consumption of an affluent diet. N Engl J Med. 1991, 325: 1704-1708. 10.1056/NEJM199112123252405.

Ferdowsian HR, Barnard ND: Effects of plant-based diets on plasma lipids. Am J Cardiol. 2009, 104: 947-956. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.032.

Barnard RJ, Guzy P, Rosenberg J, O’Brien L: Effects of an intensive exercise and nutrition program on patients with coronary artery disease: five-year follow-up. J Cardiac Rehab. 1983, 3: 183-190.

Navab M, Reddy ST, Van Lenten BJ, Fogelman AM: HDL and cardiovascular disease: atherogenic and atheroprotective mechanisms. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011, 8: 222-232. 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.222.

Roberts CK, Barnard RJ: Effects of exercise and diet on chronic disease. J Appl Physiol. 2005, 98: 3-30.

Ng DS, Wong NCW, Hegele RA: HDL—is it too big to fail?. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013, 9: 308-312. 10.1038/nrendo.2012.238.

Shah S, Casas J, Drenos F, Whittaker J, Deanfield J, Swerdlow DI, Holmes MV, Kivimaki M, Langenberg C, Wareham N, Gertow K, Sennblad B, Strawbridge RJ, Baldassarre D, Veglia F, Tremoli E, Gigante B, de Faire U, Kumari M, Talmud PJ, Hamsten A, Humphries SE, Hingorani AD: Causal relevance of blood lipid fractions in the development of carotid atherosclerosis: mendelian randomization analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013, 6: 63-72. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.112.963140.

Nicholls SJ, Lundman P, Harmer JA, Cutri B, Griffiths KA, Rye KA, Barter PJ, Celermajer DS: Consumption of saturated fat impairs the anti-inflammatory properties of high-density lipoproteins and endothelial function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 48: 715-720. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.080.

Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Llera-Moya M, Rodrigues A, Burke MF, Jafri K, French BC, Phillips JA, Muchsavage ML, Wilensy RL, Mohler ER, Rothblat GH, Rader DJ: Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011, 364: 127-135. 10.1056/NEJMoa1001689.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HD developed the CHIP intervention. DM, PR and LK were involved in the design of this study. JG collected all the data. LK conducted the data analyses. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the analyses, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kent, L., Morton, D., Rankin, P. et al. The effect of a low-fat, plant-based lifestyle intervention (CHIP) on serum HDL levels and the implications for metabolic syndrome status – a cohort study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 10, 58 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-10-58

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-10-58