Abstract

Background

An intravenous urogram (IVU) has traditionally been considered mandatory before treating renal and ureteric stones by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). This study was designed to see whether there is a difference in complications and the need for ancillary procedures in patients managed by ESWL for renal and ureteric calculi, according to preoperative imaging technique.

Methods

This retrospective study compared 133 patients undergoing ESWL from January 2001 to July 2002. Patients were divided into three groups according to the preoperative imaging technique used: i) IVU; ii) non-contrast enhanced helical computed tomography (UHCT); and iii) ultrasound (US) + X-ray kidney, ureter and bladder (KUB). The groups were matched in terms of age and gender, as well as location, side and size of stones.

Results

There was no statistically significantly difference for number of ESWL sessions, number of shock waves and use of ancillary procedures between the three groups. The stone-free rate was 98% for the IVU and UHCT groups, and 97% for the US + X-ray KUB group.

Conclusions

The complication rate and need for ancillary procedures was comparable across the three groups. Patients imaged by UHCT or US + X-ray KUB prior to ESWL for uncomplicated renal and ureteric stones do not require IVU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Since the introduction of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) in the early 1980s, intravenous (excretory) urograms (IVU) have been used to plan treatment for patients with renal and ureteric stones. Intravenous urograms are beneficial for displaying calyceal anatomy and its relationship to stone burden [1]. In recent years, newer modalities for imaging the urinary tract have been introduced, such as contrast computed tomography (CT urogram), non-contrast enhanced helical CT (UHCT), magnetic resonance urography and real-time ultrasonography (US), particularly power Doppler US [2]. Intravenous urography is no longer the primary modality for the initial evaluation of ureteric colic, uroseptic fever, haematuria and obstructive uropathy, which are commonly associated with renal and ureteric stones [3]. Intravenous urograms have also been replaced by UHCT and US + X-ray kidney, ureter and bladder (KUB) in the radiological evaluation of suspected reno-ureteric colic presenting to the emergency room. Approximately 10 million urograms were obtained in the USA in 1975. Just two decades later, the number of IVUs performed dropped to under 0.6 million per year [4].

Many recent studies have confirmed that UHCT has high sensitivity and specificity in the evaluation of acute flank pain [5, 6]. Ultrasonography with X-ray KUB is not as sensitive as UHCT; however, it has the advantages of lower radiation dose and easy availability, and it avoids the hazards of a contrast agent [7].

Non-contrast enhanced helical CT is quicker to perform and has fewer contraindications, although it brings a potentially higher radiation dosage to the patient [7]. A combination of X-ray KUB and US exposes patients to the least radiation of these three modalities commonly used in the evaluation of suspected renal and ureteric stones.

It is clear from a review of current literature that the diagnostic accuracy of UHCT is superior to IVU in patients presenting with acute flank pain [3–6]. What is not so clear is whether UHCT or US + X-ray KUB alone could be used to plan ESWL for moderate-sized renal and ureteric stones. This study was designed to see if there is difference in the need for ancillary procedures, stone-free rate and complications in patients managed by in situ ESWL for renal and ureteric calculi among patients preoperatively imaged by either IVU, UHCT or US + X-ray KUB.

Methods

This study compared patients undergoing ESWL from January 2001 to July 2002; data was collected retrospectively. Patients were divided into three groups based upon the modality used to image the urinary tract preoperatively, that is, IVU, US + X-ray KUB or UHCT.

One hundred and thirty-three patients were included in the study; 50 in each of the IVU and UHCT groups, and 33 in the US + X-ray KUB group. Thirty-two women and 101 men participated and their mean age was 38.3 ± 12 years. One-third had family history of stone disease and 32% were recurrent stone formers. Fifty-five percent of the stones were on the left side of the body. The three groups were matched for age and gender, as well as location, side and size of stones (Table 1). Patients with ureteric stricture, a history of open surgery, residual fragments post-percutaneous surgery, malrotated kidney and ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction were excluded from the study.

The outcome variables used were number of shock waves, sessions of ESWL, need for ancillary procedures, stone-free rate, efficiency quotient (EQ) [8] and complications. Demographic data was collected from the patient charts and the data was analyzed through the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 10 software.

All patients were treated on a second-generation, Dornier MPL 9000™ echo-guided lithotripter. Patients were treated by one of two ESWL residents under the supervision of the admitting staff member. The decision about the number of shock waves and energy setting to be used was made by the residents. Treatment was started at 14 Kv and gradually increased to 20 Kv based on patient tolerance; all treatments were done under sedoanalgesia. Therapy was terminated at 100% electrode consumption or earlier if the patient could not tolerate it or if complete fragmentation was noted on continuous real-time sonography. Post-treatment evaluation was made by a radiologist through plain X-ray and/or ultrasound; evaluations were reviewed by the admitting urologist and a decision regarding further treatment made. Patients were declared stone free if there was no radiological evidence of a stone at three months.

Results

Our results indicate that there is no difference in the need for ancillary procedure, stone-free rate and complications in the various groups.

The mean number of ESWL sessions required was 1.7 and mean shock waves were 2854; the difference between the three groups was not significant (P = 0.15 and 0.25, respectively). Only three (2.3%) patients required ancillary procedures. Two patients needed placement of a percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) catheter and one required ureteroscopy. Both patients needing PCN placement developed significant steinstrasse in a single functioning kidney. None of the patients required ancillary procedures for the primary stone.

The stone-free rate was 98% each for the IVU and UHCT groups, and 97% for the US + X-ray KUB group. The EQ was calculated as 60, 70 and 59 for the IVU, UHCT and US + X-ray KUB groups, respectively.

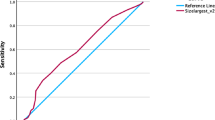

Overall 11% of patients had significant complications. Six patients in the IVU group and two in the US + X-ray KUB group developed steinstrasse, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.43). Similarly, five patients – one in each of the IVU and US + X-ray KUB groups, and three in the UHCT group – developed colic, and required admission (Figure 1). Two patients developed a post-treatment urinary tract infection.

Discussion

Acute flank pain is the most common urological presentation in the emergency room. The diagnostic workup requires comprehensive history-taking, physical examination and radiological investigation. Although the present day urologist's armamentarium is replete with investigative tools, the ideal initial radiological workup remains controversial [9].

Urinary tract imaging is required prior to ESWL to identify the cause and degree of obstruction. Obstruction most commonly is due to stones, but may have many other aetiologies. Urinary tract imaging can also determine the site and size of the stone and delineate the intracalyceal anatomy. Intravenous urogram has been the standard imaging modality in uroradiology since the 1930s [10]. It is able to demonstrate the anatomy of the entire urinary tract, it localizes the site and level of obstruction, and provides a gross assessment of excretory renal function. Some of its potential drawbacks, however, are its associated contrast reaction, inability to identify radiolucent calculi, contraindications to use in renal failure and, often it takes long time for acquiring delayed films in cases of obstruction.

In recent years, UHCT has proved to be an accurate radiographic modality [5]. The potential benefit of UHCT is its use in patients with contrast allergies, pre-existing renal failure and unclear clinical diagnosis mimicking renal colic. Unenhanced helical CT has proven to be an accurate, safe and rapid examination for diagnosing and treating patients presenting with acute flank pain. Helical CT can be used in place of IVU to plan treatment of patients with flank pain caused by obstructing ureteral stones. Stones that are larger than 5 mm, located within the proximal two-thirds of the ureter and seen on two or more consecutive CT images are more likely to require endoscopic removal, lithotripsy, or both. Computed tomography is adequate for both diagnosis and treatment. Besides stone visualization, UHCT detects obstructions by several indirect signs, such as pyelo-ureteral dilatation, perinephric and periureteral stranding, renal enlargement, renal sinus fat blurring and rim sign [11–13], which are useful when a stone is not readily identifiable. The superiority of UHCT compared with IVU in terms of sensitivity and specificity has been confirmed in a number of recent clinical trials [4–6].

Identification of concomitant anatomical abnormalities and coexisting urinary (acute pyelonephritis, subcapsular renal haematoma) and non-urinary abnormalities is important for making therapeutic decisions [14]. Using a functional study (IVU, magnetic resonance, CT urography and radioisotope studies) ensures that UPJ obstruction cannot be missed. Non-calculus ureteric obstruction can be identified on UHCT by indirect signs such as ureteric dilatation and peri-ureteric stranding, and on US by hydroureter. The findings of this study indicate that, in a selected group of patients, contrast study prior to treating ≤ 20 mm renal and ureteric stones by ESWL is not necessary.

Conclusions

For small to moderate-sized renal or ureteric stones (up to 20 mm), the need for ancillary procedures following ESWL depends upon the patency of the distal tract; it does not differ according to preoperative image techniques of either US + X-ray KUB, UHCT or IVU. Therefore, we feel that patients who are imaged by either US + X-ray KUB or UHCT do not require IVU for planning ESWL. However, a prospective trial in which patients undergoing ESWL are imaged by both UHCT and IVU will provide more conclusive results.

References

Sampaio FJ, Aragao AH: Inferior pole collecting system anatomy: its probable role in extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy. J Urol. 1992, 147: 322-324.

Shokier AA, Abdulmaaboud M: Prospective comparison of non-enhanced helical computerized tomography and Doppler ultrasonography for the diagnosis of renal colic. J Urol. 2001, 165: 1082-1084.

Miller OF, Rineer SK, Reichard SR, Buckley RG, Donovan MS, Graham IR, Goff WB, Kane CJ: Prospective comparison of unenhanced spiral computed tomography and intravenous urogram in the evaluation of acute flank pain. Urology. 1998, 52: 982-987. 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00368-9.

Pollack HM: Uroradiology. In A History of the Radiological Science. Edited by: Gagliardi RA, McCLennan BL. 1996, Reston Virginia: American Roentgen Society, 237-238.

Ahmed NA, Ather MH, Rees J: Unenhanced helical CT in the evaluation of acute flank pain. Int J Urol. 2003, 10: 287-292. 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00628.x.

Wong SK, Ng LG, Tan BS, Cheng CW, Chee CT, Chan LP, Lo HG: Acute renal colic: value of unenhanced spiral computed tomography compared with intravenous urography. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2001, 30: 568-572.

Denton ER, Mackenzie A, Greenwell T, Popert R, Rankin SC: Unenhanced helical CT for renal colic – is the radiation dose justifiable?. Clin Radiol. 1999, 54: 444-447.

Clayman R, McClennan B, Garvin T: Lithostar: An electromagnetic acoustic unit for extracorporeal lithotripsy. J Endourol. 1989, 3: 307-310.

Yilmaz S, Sindel T, Arslan G, Ozkaynak C, Karaali K, Kabaalioglu A, Luleci E: Renal colic: comparison of spiral CT, US and IVU in the detection of ureteral calculi. Eur Radiol. 1998, 8: 212-217. 10.1007/s003300050364.

Swick M: Demonstration kidneys, ureter, bladder and urethra by x-ray using intravenous administration of new contrast medium uroselectan [German]. Klin Wschr. 1929, 8: 2085-2087.

Smith RC, Levine J, Dalrymple CN, Barish M, Rosenfield AT: Acute flank pain: a modern approach to diagnosis and management. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1999, 20: 108-135.

Vieweg J, The C, Freed K, Leder RA, Smith RH, Nelson RH, Preminger GM: Unenhanced helical computerized tomography for the evaluation of patients with acute flank pain. J Urol. 1998, 160: 679-684. 10.1097/00005392-199809010-00010.

Guest AR, Cohan RH, Korobkin M, Platt JF, Bundschu CC, Francis IR, Gebramarium A, Murray UM: Assessment of the clinical utility of the rim and comet-tail signs in differentiating ureteral stones from phleboliths. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001, 177: 1285-1291.

Ahmed NA, Ather MH, Rees J: Incidental diagnosis of diseases on un-enhanced helical computed tomography performed for ureteric colic. BMC Urol. 2003, 3: 2-10.1186/1471-2490-3-2.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/2/15/prepub

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

MHA conceived of the idea for the study, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. NF collected data and helped in writing the manuscript. SA collected data and analyzed results. MNS conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ather, M.H., Faruqui, N., Akhtar, S. et al. Is an excretory urogram mandatory in patients with small to medium-sized renal and ureteric stones treated by extra corporeal shock wave lithotripsy?. BMC Med 2, 15 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-2-15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-2-15