Abstract

Using the theory of fixed point index, we establish new results for the existence of nonzero solutions of Hammerstein integral equations with reflections. We apply our results to a first-order periodic boundary value problem with reflections.

MSC:34K10, 34B15, 34K13.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In a recent paper, Cabada and Tojo [1] studied, by means of methods and results present in [2, 3], the first-order operator coupled with periodic boundary value conditions, describing the eigenvalues of the operator and providing the expression of the associated Green’s function in the nonresonant case. One motivation for studying this particular problem is that differential equations with reflection of the argument have seen growing interest along the years; see, for example, the papers [1, 4–13] and references therein. In [1], the authors provide the range of values of the real parameter ω for which the Green’s function has constant sign and apply these results to prove the existence of constant sign solutions for the nonlinear periodic problem with reflection of the argument

The methodology, analogous to the one utilized by Torres [14] in the case of ordinary differential equations, consists of two steps. First, we rewrite problem (1.1) as a Hammerstein integral equation with reflections of the type

where the kernel k has constant sign. Then we make use of the well-known Guo-Krasnosel’skiĭ theorem on cone compression-expansion (see, for example, [15]).

In this paper, we continue the study of [1] and we prove new results regarding the existence of nontrivial solutions of Hammerstein integral equations with reflections of the form

where the kernel k is allowed to be not of constant sign. In order to do this, we extend the results of [16, 17], valid for Hammerstein integral equations without reflections, to the new context. We make use of a cone of functions that are allowed to change sign combined with the classical fixed point index for compact maps (we refer to [18] or [15] for further information). As an application of our theory we prove the existence of nontrivial solutions of the periodic problem with reflections (1.1).

2 The case of kernels that change sign

We begin with the case of kernels that are allowed to change sign. We impose the following conditions on k, f, g that occur in the integral equation:

where T is fixed in .

(C1) The kernel k is measurable, and for every we have

(C2) There exist a subinterval , a measurable function Φ with a.e. and a constant such that

(C3) The function g satisfies that , a.e. and

(C4) The nonlinearity satisfies the Carathéodory conditions, that is, is measurable for each fixed u and v and is continuous for a.e. , and for each , there exists such that

We recall the following definition.

Definition 2.1 Let X be a Banach Space. A cone on X is a closed, convex subset of X such that for and and .

Here, we work in the space , endowed with the usual supremum norm, and we use the cone

Note that .

The cone K has been essentially introduced by Infante and Webb in [16] and later used in [17, 19–27]. K is similar to a type of cone of nonnegative functions first used by Krasnosel’skiĭ; see, e.g., [28], and Guo, see, e.g., [15]. Note that functions in K are positive on the subset but are allowed to change sign in .

We require some knowledge of the classical fixed point index for compact maps; see for example [18] or [15] for further information. If Ω is a bounded open subset of K (in the relative topology) we denote by and ∂ Ω the closure and the boundary relative to K. When D is an open bounded subset of X, we write , an open subset of K.

The next lemma is a direct consequence of classical results from degree theory, for details see [15].

Lemma 2.2 Let D be an open bounded set with and . Assume that is a compact map such that for . Then the fixed point index has the following properties:

-

(1)

If there exists such that for all and all , then .

-

(2)

If for all and for every , then .

-

(3)

Let be open in X with . If and , then F has a fixed point in . The same result holds if and .

Definition 2.3 We use the following sets:

The set was introduced in [26] and is equal to the set called in [17]. The notation makes it clear that choosing c as large as possible yields a weaker condition to be satisfied by f in Lemma 2.6. A key feature of these sets is that they can be nested, that is,

Theorem 2.4 Assume that hypotheses (C1)-(C4) hold for some . Then F maps into K and is compact. When these hypotheses hold for each , F is compact and maps K into K.

Proof For and , we have

and

Therefore, we have that for every .

The compactness of F follows from the fact that the Hammerstein integral operator that occurs in (2.1) is compact (this a consequence of Proposition 3.1 of Chapter 5 of [29]). □

In the sequel, we give a condition that ensures that, for a suitable , the index is 1 on .

Lemma 2.5 Assume that

() there exists such that

where

and

Then the fixed point index, , is equal to 1.

Proof We show that for every and for every . In fact, if this does not happen, there exist and such that , that is,

Taking the absolute value and then the supremum for gives

This contradicts the fact that and proves the result. □

Let us see now a condition that guarantees the index is equal to zero on for some appropriate .

Lemma 2.6 Assume that

() there exist such that such that

where

and

Then .

Proof Let , then . We prove that

In fact, if not, there exist and such that . Then we have

Thus we get, for ,

Taking the minimum over gives a contradiction. □

The above lemmas can be combined to prove the following theorem. Here, we deal with the existence of at least one, two or three solutions. We stress that, by expanding the lists in conditions (S5), (S6) below, it is possible to state results for four or more positive solutions; see for example the paper by Lan [30] for the type of results that might be stated. We omit the proof which follows directly from the properties of the fixed point index stated in Lemma 2.2(3).

Theorem 2.7 The integral equation (2.1) has at least one nonzero solution in K if either of the following conditions hold:

(S1) There exist with such that () and () hold:

(S2) There exist with such that () and () hold.

The integral equation (2.1) has at least two nonzero solutions in K if one of the following conditions hold:

(S3) There exist with such that (), () and () hold.

(S4) There exist with and such that (), () and () hold.

The integral equation (2.1) has at least three nonzero solutions in K if one of the following conditions hold:

(S5) There exist with and such that (), (), () and () hold.

(S6) There exist with and such that (), (), () and () hold.

3 The case of nonnegative kernels

We now assume the functions k, f, g that occur in (2.1) satisfy the conditions (C1)-(C4) in the previous section, where (C2) and (C4) are replaced with the following.

() The kernel k is nonnegative for and a.e. and there exist a subinterval , a measurable function Φ, and a constant such that

() The nonlinearity satisfies Carathéodory conditions, that is, is measurable for each fixed u and v and is continuous for a.e. , and for each , there exists such that

These hypotheses enable us to work in the cone of nonnegative functions

that is smaller than the cone (2.2). It is possible to show that F is compact and leaves the cone invariant. The conditions on the index are given by the following lemmas; the proofs are omitted as they are similar to the ones in the previous section.

Lemma 3.1 Assume that

() there exists such that , where

Then .

Lemma 3.2 Assume that

() there exist such that , where

Then .

A result equivalent to Theorem 2.7 is clearly valid in this case, with nontrivial solutions belonging to the cone (3.1).

4 The case of kernels with extra positivity

We now assume the functions k, f, g that occur in (2.1) satisfy the conditions (C1), (), (C3) and () with ; in particular note that the kernel satisfies the stronger positivity requirement

These hypotheses enable us to work in the cone

Remark 4.1 Note that a function in that possesses a nontrivial norm, has the useful property that is strictly positive on .

Once again F is compact and leaves the cone invariant. The assumptions on the index are as follows.

Lemma 4.2 Assume that

() there exists such that , where

Then .

Lemma 4.3 Assume that

() there exist such that  , where

, where

Then .

A result similar to Theorem 2.7 holds in this case.

Remark 4.4 If f is defined only on we can extend it to considering firstly

and secondly

This approach that follows the one of Lan [31] and that has been exploited in [32–34] in the context of problems without reflections, is useful to prove the existence of multiple positive solutions in presence of strong singularities in the nonlinearity f. For a related result, that uses the principal eigenvalue of the corresponding linearized equation, see [35].

Remark 4.5 Note that results similar to Sections 2, 3 and 4 hold when the kernel k is negative on a strip, negative and strictly negative. This gives nontrivial solutions that are negative on an interval, negative and strictly negative, respectively.

5 An application

We now turn our attention to the first-order functional periodic boundary value problem

We apply the shift argument of [1] (a similar idea has been used in [14, 36]), by fixing and considering the equivalent expression

Following the ideas developed in [1], we can verify that the functional boundary value problem (5.3)-(5.4) can be rewritten into a Hammerstein integral equation of the type

Also, can be expressed in the following way (see [1] for details):

The results that follow are meant to prove that we are under the hypothesis of Theorem 2.4.

The sign properties of the kernel (5.6) can be summarized as follows.

Theorem 5.1 [1]

Let .

-

(1)

If then is strictly positive on .

-

(2)

If then is strictly negative on .

-

(3)

If then vanishes on and is strictly positive on .

-

(4)

If then vanishes on P and is strictly negative on .

-

(5)

If then is changes sign on .

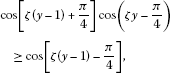

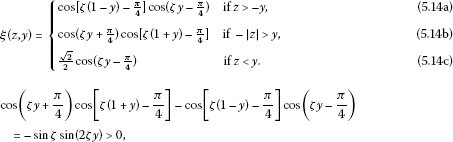

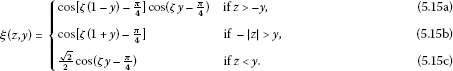

In [1], some existence results has been obtained for problem (5.3)-(5.4) when , i.e., when the kernel k has constant sign on . But nothing is obtained for the changing sign case. Still, there are some things to be said about the kernel k when . First, realize that, using the trigonometric identities and and making the change of variables , , we can express k as

The following lemma relates the sign of k for ζ positive and negative.

Lemma 5.2 [1]

where is the kernel for the value ζ.

Now we have the following result.

Lemma 5.3 The following hold:

-

(1)

If , then k is strictly positive in

-

(2)

If , k is strictly negative in S.

Proof By Lemma 5.2, it is enough to prove that k is strictly positive in S for . We do here the proof for the connected component of S. For the other one, the proof is analogous.

If , then , and hence .

Also, if , then and, therefore, .

If , then so .

If , then so .

If , then so .

With these inequalities the result is straightforward from equation (5.7). □

Lemma 5.4 If then where Φ admits the following expression

and β is the only solution of the equation

in the interval .

Proof Let

then

Observe that implies and , therefore, . Furthermore, since ,

Hence, equation (5.8) has a unique solution β in . Besides, since , we have that . Furthermore, it follows that

Now, realize that

while .

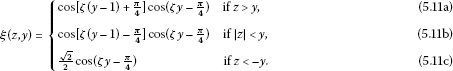

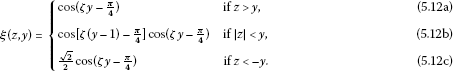

We study now the different cases for the value of y.

-

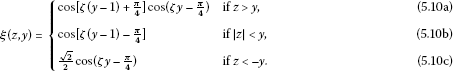

If , then

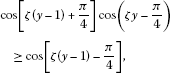

It is straightforward that , so . By our study of equation (5.8), it is clear that

Therefore, and .

-

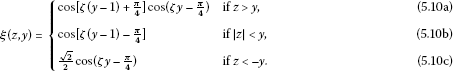

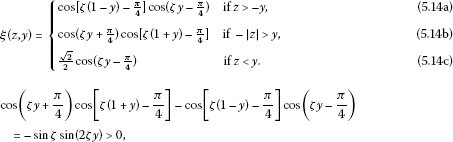

If , then ξ is as in (5.10a)-(5.10c) and , but in this case

so and .

-

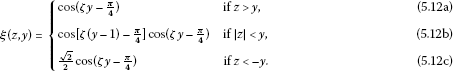

If , then

We have that

therefore and .

-

If , then

, so and .

-

If , then

Let , then

if and only if

which is true as and our study of equation (5.8). Hence, .

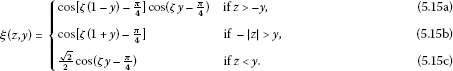

-

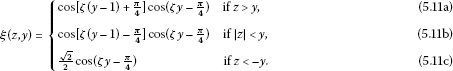

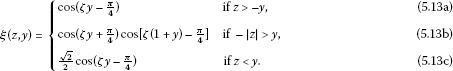

If , then ξ is the same as in (5.13a)-(5.13c) but in this case

so .

-

If , then

then .

-

If , then

Since

.

It follows, by studying the arguments of the cosines involved, that , therefore for all . □

We now give a technical lemma that will be used afterward.

Lemma 5.5 Let be a symmetric function with respect to p, decreasing in . Let be an affine function such that . Under these hypotheses, the following hold:

-

(1)

If or then .

-

(2)

If or then .

-

(3)

If then if and only if .

-

(4)

If then if and only if .

Remark 5.6 An analogous result can be established, with the proper changes in the inequalities, if f is increasing in .

Proof It is clear that if and only if , so (1) and (2) are straightforward. Also, realize that, since g is affine, we have that .

Let us prove (3) as (4) is analogous:

Therefore if and only if . □

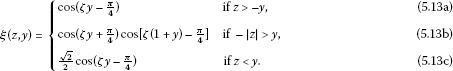

Lemma 5.7 Let and such that . Then

where

Proof We know by Lemma 5.3 that k is positive in . Furthermore, it is proved in [1] that

so, differentiating and doing the proper substitutions we get that

Therefore, in , which means that any minimum of k with respect to t has to be in the boundary of the differentiable regions of . Thus, it is clear that, in ,

By definition, . Also, realize that the arguments of the cosine in (5.7) are affine functions and that the cosine function is strictly decreasing in and symmetric with respect to zero. We can apply Lemma 5.5 to get

Finally, we have to compare the cases (5.17b) with (5.17c) for and (5.17d) with (5.17c) for . Using again Lemma 5.5, we obtain the following inequality:

Thus, for .

To compare (5.17d) with (5.17c) for realize that k is continuous in the diagonal (see [1]). Hence, since the expressions of (5.17d) and (5.17c) are already locally minimizing (in their differentiable components) for the variable z, it is clear that for . Therefore,

It is easy to check that the following order holds:

Thus, we get the following expression:

To find the infimum of this function, we will go through several steps in which we discard different cases. First, it is easy to check the inequalities and , so we need not to think about (5.19d), (5.19g) and (5.19h) anymore.

Now, realize that . Since the cosine is decreasing in and symmetric with respect to zero this implies that .

Note that (5.19c) can be written as

Its derivative is

which only vanishes at for .

Therefore, is a maximum of the function. Since is symmetric with respect to and a is the symmetric point of b with respect to , is the infimum of (5.19c), which is contemplated in (5.19b) for .

Making the change of variables , we have that (5.19f) can be written as

Since , it is clear now that  in .

in .

Let

Then

Since the argument in the cosine of the numerator is in the interval for , it is clear that for , which implies that is increasing in that interval and (5.19b) and (5.19f) reach their infimum in the left extreme point of their intervals of definition.

We have then that

The third element of the set is clearly greater or equal than the first. The second element is . Since is increasing in ,

Therefore,

□

Remark 5.8 It is easy to find an upper estimate of . Just assume .

We can do the same study for . The proofs are almost the same, but in this case the calculations are much easier.

Lemma 5.9 If then where Φ admits the following expression:

Proof This time, a simplified version of inequality (5.9) holds,

so we only need to study two cases. If , we are in the same situation as in the case studied in Lemma 5.4. Hence, . If we are in the same situation as in the case . Therefore, . □

Lemma 5.10 Let and such that . Then

where

Proof Ψ is as in (5.18a)-(5.18d), but we get the simpler expression

By the same kind of arguments used in the proof of Lemma 5.7, we get the desired result. □

Lemma 5.11

Proof First of all, if , then . The solution of the problem , is clearly , but at the same time it has to be of the kind in equation (5.5), so . This proves the first part.

If , then

We make two observations here.

From equation (5.6), it follows that and for a.e. . Hence, for and a function , using the change of variables , , we have that

Therefore, . The second observation is that, taking into account Lemma 5.3, is positive in , so

Using the same kind of arguments as in Lemma 5.3, it follows that is negative in if and if , so it is enough to compute where .

With the change of variable ,

where

and

It follows that

With these facts, we conclude that there is a unique maximum of the function in the interval , precisely where , this is, for and, therefore, the statement of the theorem holds. □

Lemma 5.12 Let and . Then

Proof It follows that

Therefore, , this is,

Using similar arguments to the ones used in the proof of Lemma 5.7, we can show that

□

With the same method, we can prove the following corollary.

Corollary 5.13 Let and . Then

Remark 5.14 If , then

just because of the observation in the proof of Lemma 5.11.

Now we can state conditions () and () for the special case of problem (5.1)-(5.2):

() Let

There exist and such that ,ORthere exist and such that

() There exist such that such that

where

Theorem 5.15 Let . Let such that . Let

Problem (5.1)-(5.2) has at least one nonzero solution in K if either of the following conditions hold:

(S1) There exist with such that () and () hold.

(S2) There exist with such that () and () hold.

The integral equation (2.1) has at least two nonzero solutions in K if one of the following conditions hold:

(S3) There exist with such that (), () and () hold.

(S4) There exist with and such that (), () and () hold.

The integral equation (2.1) has at least three nonzero solutions in K if one of the following conditions hold:

(S5) There exist with and such that (), (), () and () hold.

(S6) There exist with and such that (), (), () and () hold.

5.1 Example

Consider problem (5.1)-(5.2) with

Let , , , , , . Conditions (C1)-(C3) are clearly satisfied by the results proved before. (C4) follows the expression of h, so we are in the hypothesis of Theorem 2.4. Also,

Clearly, and , so condition (S2) in the previous theorem is satisfied and, therefore, the problem (5.1)-(5.2) has at least one solution.

References

Cabada A, Tojo FAF: Comparison results for first order linear operators with reflection and periodic boundary value conditions. Nonlinear Anal. 2013, 78: 32-46.

Cabada A, Cid JA: On comparison principles for the periodic Hill’s equation. J. Lond. Math. Soc. 2012, 86: 272-290. 10.1112/jlms/jds001

Cabada A, Cid JA, Máquez-Villamarín B: Computation of Green’s functions for boundary value problems with Mathematica. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 219: 1919-1936. 10.1016/j.amc.2012.08.035

Aftabizadeh AR, Huang YK, Wiener J: Bounded solutions for differential equations with reflection of the argument. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1988, 135: 31-37. 10.1016/0022-247X(88)90139-4

Andrade D, Ma TF: Numerical solutions for a nonlocal equation with reflection of the argument. Neural Parallel Sci. Comput. 2002, 10: 227-233.

Gupta CP: Existence and uniqueness theorems for boundary value problems involving reflection of the argument. Nonlinear Anal. 1987, 11: 1075-1083. 10.1016/0362-546X(87)90085-X

Gupta CP: Two-point boundary value problems involving reflection of the argument. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 1987, 10: 361-371. 10.1155/S0161171287000425

Ma TF, Miranda ES, de Souza Cortes MB: A nonlinear differential equation involving reflection of the argument. Arch. Math. 2004, 40: 63-68.

O’Regan D: Existence results for differential equations with reflection of the argument. J. Aust. Math. Soc. A 1994, 57: 237-260. 10.1017/S1446788700037538

O’Regan D, Zima M: Leggett-Williams norm-type fixed point theorems for multivalued mappings. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 187: 1238-1249. 10.1016/j.amc.2006.09.035

Piao D: Pseudo almost periodic solutions for differential equations involving reflection of the argument. J. Korean Math. Soc. 2004, 41: 747-754.

Piao D: Periodic and almost periodic solutions for differential equations with reflection of the argument. Nonlinear Anal. 2004, 57: 633-637. 10.1016/j.na.2004.03.017

Wiener J, Aftabizadeh AR: Boundary value problems for differential equations with reflection of the argument. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 1985, 8: 151-163. 10.1155/S016117128500014X

Torres PJ: Existence of one-signed periodic solutions of some second-order differential equations via a Krasnoselskii fixed point theorem. J. Differ. Equ. 2003, 190: 643-662. 10.1016/S0022-0396(02)00152-3

Guo D, Lakshmikantham V: Nonlinear Problems in Abstract Cones. Academic Press, Boston; 1988.

Infante G, Webb JRL: Three point boundary value problems with solutions that change sign. J. Integral Equ. Appl. 2003, 15: 37-57. 10.1216/jiea/1181074944

Infante G, Webb JRL: Nonzero solutions of Hammerstein integral equations with discontinuous kernels. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2002, 272: 30-42. 10.1016/S0022-247X(02)00125-7

Amann H: Fixed point equations and nonlinear eigenvalue problems in ordered Banach spaces. SIAM Rev. 1976, 18: 620-709. 10.1137/1018114

Franco D, Infante G, O’Regan D: Positive and nontrivial solutions for the Urysohn integral equation. Acta Math. Sin. 2006, 22: 1745-1750. 10.1007/s10114-005-0782-3

Franco D, Infante G, O’Regan D: Nontrivial solutions in abstract cones for Hammerstein integral systems. Dyn. Contin. Discrete Impuls. Syst., Ser. A, Math. Anal. 2007, 14: 837-850.

Fan H, Ma R: Loss of positivity in a nonlinear second order ordinary differential equations. Nonlinear Anal. 2009, 71: 437-444. 10.1016/j.na.2008.10.117

Infante G: Eigenvalues of some non-local boundary-value problems. Proc. Edinb. Math. Soc. 2003, 46: 75-86.

Infante G, Pietramala P: Nonlocal impulsive boundary value problems with solutions that change sign. 1124. In Mathematical Models in Engineering, Biology and Medicine: Proceedings of the International Conference on Boundary Value Problems Edited by: Cabada A, Liz E, Nieto JJ. 2009, 205-213.

Infante G, Pietramala P: Perturbed Hammerstein integral inclusions with solutions that change sign. Comment. Math. Univ. Carol. 2009, 50: 591-605.

Infante G, Webb JRL: Loss of positivity in a nonlinear scalar heat equation. Nonlinear Differ. Equ. Appl. 2006, 13: 249-261. 10.1007/s00030-005-0039-y

Infante G, Webb JRL: Nonlinear nonlocal boundary value problems and perturbed Hammerstein integral equations. Proc. Edinb. Math. Soc. 2006, 49: 637-656. 10.1017/S0013091505000532

Nieto JJ, Pimentel J: Positive solutions of a fractional thermostat model. Bound. Value Probl. 2013., 2013: Article ID 5

Krasnosel’skiĭ MA, Zabreĭko PP: Geometrical Methods of Nonlinear Analysis. Springer, Berlin; 1984.

Martin RH: Nonlinear Operators and Differential Equations in Banach Spaces. Wiley, New York; 1976.

Lan KQ: Multiple positive solutions of Hammerstein integral equations with singularities. Differ. Equ. Dyn. Syst. 2000, 8: 175-195.

Lan KQ: Multiple positive solutions of Hammerstein integral equations and applications to periodic boundary value problems. Appl. Math. Comput. 2004, 154: 531-542. 10.1016/S0096-3003(03)00733-1

Infante G: Positive solutions of some nonlinear BVPs involving singularities and integral BCs. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst., Ser. S 2008, 1: 99-106.

Infante G: Positive solutions of nonlocal boundary value problems with singularities. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2009, 2009: 377-384. suppl.

Infante, G, Pietramala, P: The displacement of a sliding bar subject to nonlinear controllers. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Differential & Difference Equations and Applications. Springer, Berlin (in press)

Webb JRL: A class of positive linear operators and applications to nonlinear boundary value problems. Topol. Methods Nonlinear Anal. 2012, 39: 221-242.

Webb JRL, Zima M: Multiple positive solutions of resonant and non-resonant nonlocal boundary value problems. Nonlinear Anal. 2009, 71: 1369-1378. 10.1016/j.na.2008.12.010

Acknowledgements

It is a great pleasure for us to dedicate this paper to Professor Jean Mawhin on the occasion of his seventieth birthday.

A. Cabada was partially supported by FEDER and Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain, project MTM2010-15314. This paper was partially written during the visit of G. Infante to the Departamento de Análise Matemática of the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. G. Infante is grateful to the people of the aforementioned Departamento for their kind and warm hospitality. F.A.F. Tojo was partially supported by Diputación de A Coruña, Bolsas para Investigación 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The three authors have participated into the obtained results. The collaboration of each one cannot be separated in different parts of the paper. All of them have made substantial contributions to the theoretical results. The three authors have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cabada, A., Infante, G. & Fernández Tojo, F.A. Nontrivial solutions of Hammerstein integral equations with reflections. Bound Value Probl 2013, 86 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-2770-2013-86

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-2770-2013-86