Abstract

Background

Discretionary salt use varies according to socio-demographic factors. However, it is unknown whether salt knowledge and beliefs mediate this relationship. This study examined the direct and indirect effect of socio-demographic factors on salt knowledge and discretionary salt use in a sample of 530 Australian adults.

Methods

An internet based cross-sectional survey was used to collect data for this study. Participants completed an online questionnaire which assessed their salt knowledge, beliefs and salt use behaviour. Mplus was used to conduct structural equation modelling to estimate direct and indirect effects.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 49.2 years, and about a third had tertiary education. Discretionary salt use was inversely related to age (r=-0.11; p<0.05), and declarative salt knowledge (knowledge of factual information) scores (r = -0.17; p<0.01), but was positively correlated with misconceptions about salt (r = 0.09; p<0.05) and beliefs about the taste of salt (r = 0.51; p<0.001). Structural equation modelling showed age, education and gender were indirectly associated with the use of discretionary salt through three mediating pathways; declarative salt knowledge, misconceptions about salt and salt taste beliefs.

Conclusions

Inequalities observed between socio-demographic groups in their use of discretionary salt use can potentially be reduced through targeted salt knowledge and awareness campaigns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

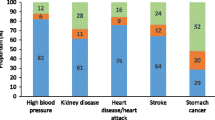

Higher intakes of dietary salt intake have been shown to increase blood pressure [1, 2] and may have possible role in increased risk of stroke [3, 4]. Elevated blood pressure plays a major role in the aetiology of cardiovascular disease [5].

A number of Australian studies have found that salt intake ranges between 6.4 g to 10 g per day [6–8], exceeding the recommended maximum amount of 6 g/day [9]. Similarly, data from U.S. and U.K. shows that the population salt intake exceeds the recommended amount [10, 11].

Similar to other western diets [12–14], the food categories that contribute most to Australians’ salt consumption are processed foods including bread and cereal products (32%) followed by meat products and dishes (21%) [15]. It is estimated that processed foods account for about 80% of salt in the Australian diet while discretionary salt contributes about 20% [16]. In order to achieve its population intake target of 6 g salt per day, the UK Food Standards Agency proposed a salt reduction strategy which comprises both reduction of salt in major salt contributing food categories (such as bread and cereals) as well as discretionary salt intake (i.e. salt added to the food) [17, 18].

In Australia, ischaemic heart disease and cardiovascular disease were the two leading causes of death in 2010 [19]. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease was higher among the Australians in the lowest socio-economic groups compared to those in the highest socio-economic groups [20, 21]. Higher proportions of individuals with lower levels of education were diagnosed with hypertension compared to those with higher levels of education [20].

Differences observed in dietary behaviours and diet quality are often attributed to socio-demographic factors such as age [22], gender [23], education [23–25] and income [24, 25]. Similarly, use of discretionary salt is also associated with socio-economic factors [26]. Individuals from lower income households, those with lower levels of education [26], males [27] and younger adults [28] have higher levels of discretionary salt use.

Apart from financial cost [29] and environmental factors such as access to healthier diets [30], social cognitive factors such as knowledge [31], self-efficacy [32], attitudes and beliefs [33] are often among the reasons attributed for the variation in dietary quality among the different socio-economic groups. For example, individuals with higher levels of education [31, 34–37] and higher incomes [34, 38] have been shown to have higher levels of nutrition knowledge. Similarly, women [31, 39] and older people [35, 38] tend to demonstrate higher levels of nutrition knowledge. More specifically, knowledge about salt has been found to be higher among older people and those with higher levels of education [40].

Although socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, education and income are indicators of health inequalities, unless there is a major societal change [26], little can be done in the short term to address or change these factors. Therefore, identification of modifiable, mediating factors may provide more feasible opportunities for interventions to reduce the disparities between the various socio-demographic groups.

To our knowledge, no study has examined the role of salt knowledge and beliefs as possible mediators between socio-demographic factors and discretionary salt use.

Given the importance of consumer knowledge as a likely influence on salt consumption and its importance for salt reduction policy monitoring [41], there is a need to clarify the role of salt knowledge and beliefs in relation to salt usage behaviour within the population.

Therefore, the aims of this study were 1) to examine the relationships between socio-demographic factors, salt knowledge, salt taste beliefs and discretionary salt use; and, 2) to determine the possible mediating roles of salt knowledge and salt taste beliefs in the relationships between socio-demographic status and discretionary salt use in an Australian adult population.

Methods

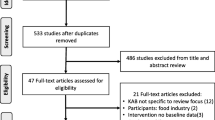

Five hundred and sixty eight invitation emails were sent to a convenience sample of online members of a market research company’s research panel. The panel members were individuals who had registered and agreed to participate in surveys in return for reward points. The invitation email included the link to the survey website which contained the questionnaire which was completed online.

Sample and procedure

The study population consisted of Australian adults above 18 years of age. The participants were invited to answer a self-administered online questionnaire, which could be completed at their convenience within 20 to 25 minutes. The study was approved by the University of Wollongong Research Ethics Committee (Ethics reference no: HE11/351).

The survey was kept open for seven days. During this period, a total of 574 individuals completed the survey; of these, 44 respondents were excluded for not meeting the screening criteria set to ensure data quality [42]. For example, respondents who completed the survey in less than one third of the average completion time were considered likely to have sped through the survey without giving much thought. Therefore, these responses were excluded from data analysis. A total of 530 usable questionnaires were used in the final analysis.

Survey questionnaire

The salt knowledge and beliefs items formed part of a larger questionnaire, which examined salt knowledge and food purchasing behaviour.

Salt knowledge and beliefs about salt taste were measured using a validated salt knowledge questionnaire [43] which contained 25 items (see Additional file 1) relating to declarative knowledge which is defined as “awareness and understanding of factual information” [44] or also known as “know that” [44] knowledge (for example, knowledge about the properties of nutrients such as salt and risk factors associated with high salt intake) and procedural knowledge or “know how” knowledge [45]. In addition, it also assessed misconceptions about salt and health. The declarative knowledge section included questions about dietary recommendations, diet-disease relationships, and the salt content of commonly eaten foods while the procedural knowledge included questions on label reading [43].

Salt knowledge scoring

All correct (i.e. accurate) responses were scored as one, while incorrect responses which included “don’t know” or “not sure” and non-responses were assigned a score of zero. Scores from three sections: dietary recommendations, diet-disease relationships, and salt content of commonly eaten foods were summed to form declarative knowledge scores and the sum of scores obtained from the label reading questions formed procedural knowledge scores. These scores were used for the subsequent analyses.

Misconceptions about salt

Misconceptions about salt were assessed using three items (Additional file 1) with five-point Likert scales ranging from “certainly wrong” to “certainly true”. Responses which indicated misconceptions were scored as one, while other responses were assigned a score of zero. For example, a score of one was given if the respondent answered “certainly true” or “probably true” for the following item “Sea salt is better than table salt”. The scores were summed to derive a total score for misconceptions about salt. Higher scores indicate higher levels of misconceptions or “false beliefs” about salt.

Beliefs about the importance of the taste of salt

Beliefs related to the taste of salt were assessed using two items; 1) “In general, low salt food tastes bad”, 2) “Salt should be used in cooking to enhance the taste of the food”. These belief items were measured on five-point Likert scales ranging from “certainly wrong” to “certainly true”. Reliability analysis showed that the two items formed one factor (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.56). The items were summed to derive a total beliefs score about the importance of the taste of salt. Higher scores indicate stronger beliefs about the importance of the taste of salt.

Socio-demographic questions

Socio-demographic questions elicited information about gender, age, highest level of education and household income (Table 1).

Discretionary salt use

Discretionary salt use was measured by two questions which had been used in a previous Australian National Nutrition Survey [47, 48]. Participants were asked to indicate the frequency of their salt use at the table and in cooking based on four response categories “always”, “usually”, “sometimes” and “never or rarely” (Table 2). Scores were assigned according to the frequencies (1 for never, 2 for sometimes etc.). Higher scores indicated higher frequency in engaging in particular behaviours. The scores were then summed to reflect discretionary salt use. Higher scores indicate higher frequency of salt use.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and Spearman bivariate correlations were calculated using SPSS Statistics version 18.0. Structural equation modelling was conducted using Mplus version 6.11 [49]. A path analysis was conducted based on the proposed theoretical model shown in Figure 1.

Mediation analyses were conducted based on the approach suggested by Hayes [50] which allows testing for indirect effects in the absence of direct associations between the independent and dependent variables. In addition, the magnitude of the of indirect effect was calculated as the ratio of indirect effect to the total effect and expressed as a percentage [51, 52].

Model fit was tested using the Tucker-Lewis (TLI) and comparative fit (CFI) indices, standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Models were deemed to be acceptable when the fit indices met the following criteria; TLI and CFI >0.95, SRMR <0.08 and RMSEA <0.06 [53]. Because of their non-normal distributions, data were analysed using MLR (maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and a chi-square test statistic) that are robust to non-normality.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants. Slightly more than half of the respondents (58.3%) were female and about a third of the respondents (27.0%) had tertiary education. Almost half of the respondents’ had annual household incomes above $60,000.

Discretionary salt use

Almost half (48.1%) of the respondents reported that they never or rarely added salt at the table, and only 35.1% of the respondents reported that they never or rarely added salt in cooking (Table 2). About a third of the study sample reported that they usually or always used salt in cooking (34.7%) and at the table (25.7%).

Relationship between socio-demographic indicators with knowledge, beliefs and discretionary salt use

Table 3 shows the associations between socio-demographic indicators and salt knowledge, salt taste beliefs and discretionary salt use. Salt use was negatively correlated with age(r=-0.11; p<0.05), declarative salt knowledge scores (r=-0.17; p<0.001), and positively associated with the misconceptions score (r=0.09; p<0.05) and salt taste beliefs (r=0.51; p<0.001). However no significant association was found between procedural knowledge scores and salt use.

Structural equation modelling

Structural equation modelling based on the proposed theoretical model (Figure 1) showed the data were a poor fit (χ2(4) = 13.07, p=0.01, CFI = 0.97, TFI = 0.78, SRMR = 0.02, RMSEA =0.07). The model was retested with additional paths between gender, age and salt taste beliefs based on the suggested modification indices and previous literature which indicated there are differences in food beliefs between genders [54] and age groups [55]. The final model (Figure 2) showed that the data were a good fit (χ2(2) = 1.20, p=0.05, CFI = 1.00, TFI = 1.03, SRMR = 0.01, RMSEA =0.00).

Standardised regression co-efficient based on final model. Gender is coded as 1= male, 2 = female; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; †path included in the analysis based on suggested modification indices; only statistically significant (p<0.05) paths are shown in this figure. Indirect paths are reported in Table 4 due to space limitations.

The model (Figure 2) explained 27.7% of variation in discretionary salt use. Age (β=0.17, p<0.001), gender (β=0.13, p<0.01) and education (β=0.15, p<0.01) were directly associated with declarative salt knowledge scores, with older adults, females and those with higher levels of education more likely to have higher levels of declarative salt knowledge while household income (β=0.13, p<0.01) was positively associated with procedural knowledge. Only education was found to have a significant inverse relationship with the misconceptions about salt (β=-0.14, p<0.01).

Of the socio-demographic predictors, only age and gender were directly associated with salt taste beliefs. Older people (β=-0.09, p <0.05) and females (β =-0.13, p<0.01) were more likely to have lower levels of salt taste beliefs. Salt taste beliefs had the strongest positive association (β = 0.50, p<0.001) with salt use followed by declarative knowledge (β =-0.12, p<0.01).

Mediation analysis

Table 4 shows the direct and indirect relationships between socio-demographic factors, declarative salt knowledge, misconceptions and beliefs with discretionary salt use.

Education had a significant negative indirect effect on salt use (β =-0.03, p<0.05) through two paths 1) declarative knowledge which accounted for 50% of the total effect of education on salt (β = -0.02, p<0.05) and 2) misconception about salt and salt taste beliefs which accounted for 25% of the total effect (β =-0.01, p<0.05). Similarly, age had a significant negative indirect effect on salt use through two paths 1) declarative knowledge (β =-0.02, p<0.05) and 2) salt taste beliefs (β =-0.04, p<0.05). More than half (54%) of the total effect of age on salt use was mediated by these two paths. The effect of gender on salt use was mediated by salt taste beliefs (β =-0.06, p<0.01). No significant direct or indirect relationship was observed between household income and salt use. Declarative knowledge demonstrated a negative direct effect on salt use (β = -0.12, p<0.01). Misconceptions about salt had a significant indirect relationship via salt taste beliefs with salt use (β =0.09, p<0.001).

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study which has examined the mediating effects of salt knowledge and salt taste beliefs on socio-demographic factors and discretionary salt use using a psychometrically validated salt knowledge questionnaire.

The proportion of respondents who reported always or usually adding salt at the table in this study (25.7%) was similar to the proportion of respondents who reported usually adding salt after cooking in National Health Survey 2001 (25.5%) [47]. The findings of this study demonstrated that age, gender and education influenced discretionary salt usage indirectly through salt knowledge (i.e. declarative knowledge), misconceptions and beliefs about the importance of the taste of salt. These findings are similar to other studies which have shown that nutrition knowledge mediates the relationships between socio-demographic factors and diet quality [56] and fruit and vegetables [57]. In addition, similar to previous findings [55] results of this study supported the importance of the role of beliefs about taste in use of discretionary salt.

However, contrary to previous findings [26], we did not observe any significant relationship between income and discretionary salt use. There is a possibility that the lack of direct relationship observed here might be caused by the interactions between the socio-demographic variables as shown in previous studies [58]. For example, income may mediate the relationship observed between education and salt use due to higher income being associated with higher levels of education.

Of the three components of knowledge, only declarative knowledge was directly and indirectly associated with salt use while misconceptions were associated with salt use indirectly through beliefs. Despite the postulated importance of procedural knowledge in dietary behaviour [39, 45, 59], and previous studies which showed that individuals who use food labels tend to exhibit healthier dietary practices [60, 61], no relationship was observed in this study between procedural knowledge and discretionary salt use. Possibly the questions used to assess procedural knowledge were not being directly related to the use of discretionary salt (the questions in this study were related to the reading of food labels). Alternatively, this could also suggests that components of declarative knowledge i.e. understanding dietary recommendations, diet-disease relationships and knowing the salt content of commonly eaten foods are important determinants of discretionary salt use and should be included in salt education campaigns.

Implications for nutrition policy and communication

Evidence of modifiable factors such as knowledge and salt taste beliefs which mediate the influence of socio-demographic factors on discretionary salt use provides an opportunity for the design of effective behavioural change interventions which operate on these mediators. For example, at present, most national salt reduction strategies include consumer education and awareness campaigns [62]. Thus, the identification of cognitive mediators in this study would facilitate the creation of tailored nutrition education programmes to suit the needs of smaller segments of population. Higher use of the internet is increasingly making it possible to deliver cost effective and more interactive tailored nutrition education programme [63].

Although the influence of taste beliefs in the current study was limited to the use of discretionary salt, consumers’ perceptions about poor tasting, low salt products has been noted as one of the reasons which led to poor uptake of salt reduced products [64], and to the decision to reintroduce salt into salt reduced products [65]. This suggests that there is a need to correct the misconceptions and beliefs which exist around the use of salt in food. Changes in consumer salt taste beliefs are likely to induce changes in salt usage behaviour which might lead to the alteration of taste preferences and eventually acceptance and preference for lower salt products [66, 67].

Most countries with salt reduction initiatives have a voluntary programme for food manufacturers to reduce salt content in processed foods [62]. Even though this approach has been shown as a cost- effective way to reduce salt in the diet [68], it may take time and may vary between food companies within the same food category [69] and between countries [12, 18, 69]. Therefore, until the time when there is widespread availability of food products with lower amounts of salt, active participation from consumers will be required to reduce the salt in their diet. This includes reading food labels to choose products with lower salt content and reduce the amount of discretionary salt use.

Salt reduction initiatives should include both components; working with food industries to reformulate food products and educating consumers to reduce discretionary salt to ensure gradual reduction in preference for salt taste [28, 70]. In addition, health educators may also need to consider the most appropriate approach towards education and awareness campaigns i.e. whether to focus on a single nutrient (dietary salt) or the overall diet and behavioural factors associated with hypertension [71].

Limitations and future research directions

This study has several limitations. First, as a cross-sectional study, the findings can only be used to examine associations and not to draw inferences regarding causality. Further, results of this study might not be generalisable to the whole population due to use of convenience sampling. However, the sample appears to be more representative of the general population than samples from other surveys in which [37, 39, 72] female respondents or those with tertiary education are often over-represented. In contrast, in the present sample, the proportions of female respondents and those with tertiary education were similar to those in the general population [46].

Second, we have used self-reported use of table salt and salt in cooking as measures of discretionary salt use. Even though self-reported use of salt has been found to be correlated with actual behaviour [73], a more objective measure such as that provided by the lithium-marker technique [74] should be considered for future studies.

Third, discretionary salt use contributes less than 20% of the total amount of dietary salt in average person’s diet [16, 75] while processed foods account for about 80% of the salt in Australian diet. Therefore, measurement of discretionary salt represents only a small amount of consumers’ dietary salt intake. Further, it is possible that use of discretionary salt may be lower when foods with high salt content are consumed or prepared and therefore it may potentially underestimated total salt intake. However, previous studies have shown that that higher use of discretionary salt was associated with higher total salt intake [76, 77]. For example, analysis of 24-hour urinary sodium excretion of Australian adults between the age of 50 to 75 years found that those who reported use of salt in cooking had higher urinary sodium excretion than those who did not [78].

Fourth, the model only explained about a third of the variation in discretionary salt use. Therefore, future studies should be extended to study other factors which may mediate the relationship between socio-demographic factors and use of discretionary salt such as self-efficacy [32] and attitudes [33] and salt taste preferences. In addition, interactions between socio-demographic predictors such as education, household income and differences between the genders should also be explored. There is also a possibility that the total variation explained by the model can be increased with the addition of processed food items as outcome variables, especially those which were used to assess salt knowledge levels (e.g. processed meat, cheese).

Fifth, it should be noted that the questions on procedural knowledge in this study only focused on label reading and not on discretionary salt use. Therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting all results pertaining to procedural knowledge. Future studies should extend the scope of procedural knowledge to clarify whether the reason for a non-significant relationship observed between procedural knowledge and discretionary salt use was due to limited scope of procedural knowledge or declarative knowledge is indeed a more important component of knowledge in predicting salt use.

Finally, since only two items were used to measure the salt taste beliefs construct in this study, as expected, the internal reliability of the beliefs construct was moderately low [79]. Despite this low reliability, we found a moderate correlation between beliefs and discretionary salt use. Therefore, future studies should employ a greater number of belief items to further examine the relationship between beliefs and salt use. There is a possibility that a scale with higher reliability may increase the relationships observed between beliefs and salt use.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that declarative salt knowledge, salt beliefs and misconceptions mediate the relationships between age, gender and education with discretionary salt use. The study findings provide health promoters with opportunities to design targeted education and awareness campaigns. However, the study needs to be replicated to confirm the applicability of the findings in other populations.

References

He FJ, MacGregor GA: Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Implications for public health. J Hum Hypertens. 2002, 16 (11): 761-770. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001459.

Rose G, Stamler J, Stamler R, Elliott P, Marmot M, Pyorala K, Kesteloot H, Joossens J, Hansson L, Mancia G, et al: Intersalt: An international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24 hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion. Br Med J. 1988, 297 (6644): 319-328.

Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala N-B, Cappuccio FP: Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2009, 339: b4567-10.1136/bmj.b4567.

Gardener H, Rundek T, Wright CB, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL: Dietary sodium and risk of stroke in the Northern Manhattan study. Stroke. 2012, 43 (5): 1200-1205. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.641043.

World Health Organization: The World Health Report 2002 – Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. 2002, World Health Organization, Geneva

Charlton K, Yeatman H, Houweling F, Guenon S: Urinary sodium excretion, dietary sources of sodium intake and knowledge and practices around salt use in a group of healthy Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010, 34 (4): 356-363. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00566.x.

Beard TC, Woodward DR, Ball PJ, Hornsby H, von Witt RJ, Dwyer T: The Hobart Salt Study 1995: Few meet national sodium intake target. Med J Aust. 1997, 166: 404-407.

O’Reilly SL, Brinkman M, Giles G, English D, Nowson CA: Sodium intake and use of discretionary salt in an Australian population sample [abstract]. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010, 69: E84.

National Health and Medical Research Council: Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand, including recommended dietary intakes. [http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/n35.pdf]

Loria CM, Mussolino ME, Cogswell ME, Gillespie C, Gunn JP, Labarthe DR, Saydah S, Pavkov ME: Usual sodium intakescompared with current dietary guidelines — United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011, 60 (41): 1413-1444.

Medical Research Council: An assessment of dietary sodium levels among adults (aged 19–64) in the UK general population in. 2008, [http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/08sodiumreport.pdf], , based on analysis of dietary sodium in 24 hour urine samples

Woodward E, Eyles H, Ni Mhurchu C: Key opportunities for sodium reduction in New Zealand processed foods. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012, 36 (1): 84-89. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00829.x.

Moshfegh AJ, Holden JM, Cogswell ME, Kuklina EV, Patel SM, Gunn JP, Gillespie C, Hong Y, Merritt R, Galuska DA: Vital signs: Food categories contributing the most to sodium consumption - United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012, 61 (5): 92-98.

Thomson BM: Nutritional modelling: Distributions of salt intake from processed foods in New Zealand. Br J Nutr. 2009, 102 (5): 757-765. 10.1017/S000711450928901X.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand: How much sodium and salt are we eating?. [http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/scienceandeducation/factsheets/factsheets/howmuchsaltareweeating/]

Food Standards Australia New Zealand: Sodium and salt. [http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/scienceandeducation/factsheets/factsheets/sodiumandsalt.cfm]

FSA Salt Model. UK Salt Intakes: Modelling Salt Reductions. [http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/spreadsheets/saltmodel.xls]

Wyness LA, Butriss JL, Stanner SA: Reducing the population’s sodium intake: The UK Food Standards Agency’s salt reduction programme. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15 (2): 254-261. 10.1017/S1368980011000966.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Causes of Death, Australia. 2010, [http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/6BAD463E482C6970CA2579C6000F6AF7?opendocument]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Cardiovascular disease: Australian facts 2011. Cardiovascular disease series. Cat. no. CVD 53. 2011, AIHW, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular disease in Australia. 2006, AIHW, Canberra

Hjartåker A, Lund E: Relationship between dietary habits, age, lifestyle, and socio-economic status among adult Norwegian women. The Norwegian Women and Cancer Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998, 52 (8): 565-572. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600608.

Groth MV, Fagt S, Brøndsted L: Social determinants of dietary habits in Denmark. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001, 55 (11): 959-966. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601251.

Kant AK, Graubard BI: Secular trends in the association of socio-economic position with self-reported dietary attributes and biomarkers in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1971–1975 to NHANES 1999–2002. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10 (02): 158-167.

Mullie P, Clarys P, Hulens M, Vansant G: Dietary patterns and socioeconomic position. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010, 64 (3): 231-238. 10.1038/ejcn.2009.145.

Turrell G, Stanley L, de Looper M, Oldenburg B: Health Inequalities in Australia: Morbidity, health behaviours, risk factors and health service use. Health Inequalities Monitoring Series No 2 AIHW Cat No PHE 72. 2006, Queensland University of Technology and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Henderson L, Irving K, Gregory J, Bates CJ, Prentice A, Perks J, Swan G, Farron M: The National Diet and Nutrition Survey: adults aged 19 to 64 years—vitamin and mineral intake and urinary analysis. 2003, HMSO, London, United Kingdom

Grimes CA, Riddell LJ, Nowson CA: The use of table and cooking salt in a sample of Australian adults. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010, 19 (2): 256-260.

Monsivais P, Aggarwal A, Drewnowski A: Are socio-economic disparities in diet quality explained by diet cost?. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010, 66 (6): 530-535.

Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC: Neighborhood environments: Disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009, 36 (1): 74-81. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. e10

Parmenter K, Waller J, Wardle J: Demographic variation in nutrition knowledge in England. Health Educ Res. 2000, 15 (2): 163-174. 10.1093/her/15.2.163.

Leganger A, Kraft P: Control constructs: Do they mediate the relation between educational attainment and health behaviour?. J Health Psychol. 2003, 8 (3): 361-372. 10.1177/13591053030083006.

Wardle J, Steptoe A: Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003, 57 (6): 440-443. 10.1136/jech.57.6.440.

Dallongeville J, Marécaux N, Cottel D, Bingham A, Amouyel P: Association between nutrition knowledge and nutritional intake in middle-aged men from Northern France. Public Health Nutr. 2001, 4 (01): 27-33.

De Vriendt T, Matthys C, Verbeke W, Pynaert I, De Henauw S: Determinants of nutrition knowledge in young and middle-aged Belgian women and the association with their dietary behaviour. Appetite. 2009, 52 (3): 788-792. 10.1016/j.appet.2009.02.014.

Lin C-TJ, Yen ST: Knowledge of dietary fats among US consumers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010, 110 (4): 613-618. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.020.

Hendrie GA, Coveney J, Cox D: Exploring nutrition knowledge and the demographic variation in knowledge levels in an Australian community sample. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11 (12): 1365-1371. 10.1017/S1368980008003042.

Eckel RM, Kris-Etherton PPRD, Lichtenstein AD, Wylie-Rosett JERD, Groom AM, Stitzel KMR, Yin-Piazza SM: Americans’ awareness, knowledge, and behaviors regarding fats: 2006–2007. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009, 109 (2): 288-10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.048.

Dickson-Spillmann M, Siegrist M: Consumers’ knowledge of healthy diets and its correlation with dietary behaviour. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011, 24 (1): 54-60. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01124.x.

Webster JL, Li N, Dunford EK, Nowson CA, Neal BC: Consumer awareness and self-reported behaviours related to salt consumption in Australia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2010, 19 (4): 550-554.

World Health Organization: Strategies to monitor and evaluate population sodium consumption and sources of sodium in the diet: report of a joint technical meeting convened by WHO and the Government of Canada, October. 2010, World Health Organisation, Canada, 1-42.

Rogers F, Richarme M: The Honesty of Online Survey Respondents: Lessons Learned and Prescriptive Remedies. [http://www.decisionanalyst.com/publ_art/onlinerespondents.dai]

Sarmugam R, Worsley A, Flood V: Development and validation of a salt knowledge questionnaire. review. 2012

Colman AM: A dictionary of psychology. 2012, Oxford University Press, United Kingdom, 3

Worsley A: Nutrition knowledge and food consumption: can nutrition knowledge change food behaviour?. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2002, 11 (s3): S579-S585. 10.1046/j.1440-6047.11.supp3.7.x.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Census Community Profile Series. 2006, Australia, [http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ViewData?&action=404&documentproductno=0&documenttype=Details&tabname=Details&areacode=0&issue=2006&producttype=Community%20Profiles&&producttype=Community%20Profiles&javascript=true&textversion=false&navmapdisplayed=true&breadcrumb=PLD&&collection=census&period=2006&producttype=Community%20Profiles&#Basic%20Community%20Profile]

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Occasional paper: Measuring dietary habits in the 2001 National Health Survey Australia. 2001, [http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4814.0.55.001#APPENDIX%20A%3A%202001%20NHS%20DIETARY%20INDI]

Australian Bureau of Statistics: National Nutritional Survey Users’ Guide 1995. 1998, Canberra, [http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/CA25687100069892CA256889002102FD/$File/48010_1995.pdf]

Muthén LK, Muthén BO: Mplus User’s Guide. 1998–2011, Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, Sixth

Hayes AF: Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. ComM. 2009, 76 (4): 408-420.

Mackinnon DP, Dwyer JH: Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev. 1993, 17 (2): 144-158. 10.1177/0193841X9301700202.

Hayes AF, Preacher KJ, Myers TA: Mediation and the estimation of indirect effects in political communication research. Sourcebook for political communication research: Methods, measures, and analytical techniques. Edited by: Bucy EP, Holbert L. 2011, Routledge, New York, 434-465.

Hu LT, Bentler PM: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999, 6 (1): 1-55. 10.1080/10705519909540118.

Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisle F: Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med. 2004, 27 (2): 107-116. 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_5.

Shepherd R, Farleigh CA: Attitudes and personality related to salt intake. Appetite. 1986, 7 (4): 343-354. 10.1016/S0195-6663(86)80003-4.

McLeod ER, Campbell KJ, Hesketh KD: Nutrition knowledge: A mediator between socioeconomic position and diet quality in Australian first-time mothers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011, 111 (5): 696-704. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.02.011.

Wardle J, Parmenter K, Waller J: Nutrition knowledge and food intake. Appetite. 2000, 34 (3): 269-275. 10.1006/appe.1999.0311.

Lahelma E, Martikainen P, Laaksonen M, Aittomäki A: Pathways between socioeconomic determinants of health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004, 58 (4): 327-332. 10.1136/jech.2003.011148.

Kristal AR, Bowen DJ, Curry SJ, Shattuck AL, Henry HL: Nutrition knowledge, attitudes and perceived norms as correlates of selecting low-fat diets. Health Educ Res. 1990, 5: 467-10.1093/her/5.4.467.

Kempen E, Muller H, Symington E, Van Eeden T: A study of the relationship between health awareness, lifestyle behaviour and food label usage in Gauteng. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2012, 25 (1): 15-21.

Satia JA, Galanko JA, Neuhouser ML: Food nutrition label use is associated with demographic, behavioral, and psychosocial factors and dietary intake among African Americans in North Carolina. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005, 105 (3): 392-402. 10.1016/j.jada.2004.12.006.

Webster JL, Dunford EK, Hawkes C, Neal BC: Salt reduction initiatives around the world. J Hypertens. 2011, 29 (6): 1043-1050. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328345ed83.

Brug J, Oenema A, Campbell M: Past, present, and future of computer-tailored nutrition education. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003, 77 (4): 1028S-1034S.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake: The Food Environment: Key to Formulating Strategies for Change in Sodium Intake. 2010, Washington, [http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12818]

Campbell Soup Company: Campbell Continues to Provide Consumers with an Array of Lower-Sodium Choices. [http://investor.campbellsoupcompany.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=88650&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1586923&highlight=]

Bertino M, Beauchamp GK, Engelman K: Long-term reduction in dietary sodium alters the taste of salt. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982, 36 (6): 1134-1144.

Blais CA, Pangborn RM, Borghani NO: Effect of dietary sodium restriction on taste responses to sodium chloride: A longitudinal study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1986, 44 (2): 232-243.

Cobiac LJ, Vos T, Veerman JL: Cost-effectiveness of interventions to reduce dietary salt intake. Heart. 2010, 96 (23): 1920-1925. 10.1136/hrt.2010.199240.

Dunford EK, Eyles H, Mhurchu CN, Webster JL, Neal BC: Changes in the sodium content of bread in Australia and New Zealand between, and 2010: Implications for policy. Med J Aust. 2007, 195 (6): 346-349.

Pietinen P, Valsta LM, Hirvonen T, Sinkko H: Labelling the salt content in foods: a useful tool in reducing sodium intake in Finland. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11 (04): 335-340.

Barr SI: Reducing dietary sodium intake: The Canadian context. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010, 35 (1): 1-8. 10.1139/H09-126.

Grimes CA, Riddell LJ, Nowson CA: Consumer knowledge and attitudes to salt intake and labelled salt information. Appetite. 2009, 53 (2): 189-194. 10.1016/j.appet.2009.06.007.

Mittelmark MB, Sternberg B: Assessment of salt use at the table: comparison of observed and reported behavior. Am J Public Health. 1985, 75 (10): 1215-1216. 10.2105/AJPH.75.10.1215.

Leclercq C, Avalle V, Ranaldi L, Toti E, Ferro-Luzzi A: Simplifying the lithium-marker technique used to assess the dietary intake of household sodium in population studies. Clin Sci. 1990, 79 (3): 227-231.

Mattes RD, Donnelly D: Relative contributions of dietary sodium sources. J Am Coll Nutr. 1991, 10 (4): 383-393.

Jeffery P, Nowson C, Riddell L, Land M-A, Shaw J, Webster J, Chalmers J, Smith W, Flood V, Neal B: Salt intake in Victorian adults. Seminar - World salt awareness week. 2012, Melbourne, Victoria

Garriguet D: Sodium consumption at all ages. Health Rep. 2007, 18 (2): 47-52.

Huggins CE, O’Reilly S, Brinkman M, Hodge A, Giles GG, English DR, Nowson CA: Relationship of urinary sodium and sodium-to-potassium ratio to blood pressure in older adults in Australia. Med J Aust. 2011, 195 (3): 128-132.

Cortina JM: What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol. 1993, 78 (1): 98-104.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the survey respondents for participating in the study and the anonymous reviewers for their inputs.

Funding

This project was funded through a University of Wollongong grant to Professor Worsley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

RS and AW were responsible for the design of study. RS analysed and wrote the paper with contributions from AW. WW assisted in the data analyses. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarmugam, R., Worsley, A. & Wang, W. An examination of the mediating role of salt knowledge and beliefs on the relationship between socio-demographic factors and discretionary salt use: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 10, 25 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-25

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-25