Abstract

Background

L-carnitine-mediated beta-oxidation of fatty acids has a well established role in energy supply of oocytes and embryos. Disturbed carnitine metabolism may impair the reproductive potential in IVF and can serve as a biomarker of pregnancy outcome.

Methods

Our study was performed between March 24, 2011 and May 9, 2011. We performed 44 unselected IVF cycles, (aged 23–40 years (mean: 32.3+/−5.1 years) and had BMI of 17.3-34.7 (mean: 23.80+/−4.9). Samples were also obtained from 18 healthy women of similar age admitted for minor elective surgery to serve as control for plasma carnitine profile. Serum and follicular fluid (FF) free carnitine (FC) and 20 major acylcarnitines (ACs) were measured by ESI/MS/MS method.

Results

Serum FC and AC levels in IVF patients were comparable to those in healthy control women. In FF FC and short-chain AC concentrations were similar to those in maternal serum, however, the levels of medium-chain, and long-chain AC esters were markedly reduced (p<0.05). The serum to FF ratio of individual carnitine compounds increased progressively with increasing carbon chain length of AC esters (p<0.05). There was a marked reduction in total carnitine, FC and AC levels of serum and FF in patients with oocyte number of >9 and/or with embryo number of >6 as compared to the respective values of <9 and/or <6 (p<0.05).

Conclusions

In IVF patients with better reproductive potential the carnitine/AC pathway appears to be upregulated that may result in excess carintine consumption and relative depletion of carnitine pool. Consequently, IVF patients may benefit from carnitine supplementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Normal oocyte maturation, fertility and embryo development is closely associated with energy metabolism [1–4]. The prominent role of fatty acids in energy supply to acquire developmental competence of oocyte and early embryos has been established [5–8]. However, growing body of evidences suggests, that non-esterified fatty acid supply in excess of its metabolic utilization results in fatty acid accumulation that may compromise oocyte maturation and developmental capacity of early embryo [9–11]. Interestingly, when free fatty acid composition of serum and/or follicular fluid (FF) was analyzed it became apparent that not isolated individual fatty acids, but rather physiologically relevant ratios and /or combinations of fatty acids cause significant dysregulation of cellular processes [8].

Free fatty acids are metabolised via beta-oxidation that is mediated by L-carnitine. L-carnitine is present in free and esterified forms in tissues and body fluids. It has multiple metabolic functions including transport of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria for beta-oxidation, transfer of short- and medium-chain acyl groups from the peroxisome to mitochondria, regulation of intracellular acyl-CoA/free CoA ratio and export of toxic acyl residues from the mitochondria [12–17]. Accumulation of acylcarnitines, (AC)s therefore is regarded as indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired cellular fatty acid metabolism [18]. The importance of L-carnitine in improving oocyte quality and reproductive performance has been demonstrated in animal and human studies [19–24].

On the basis of these observations it was intriguing to investigate further the relationship between carnitine profile and reproductive potential. In women who wants to conceive a child we can only analyze the serum carnitine profile and no FF samplaes are available, therefore patients receiving IVF can be an observational model. Also testing whether L-carnitine or individual carnitine esters alone or in combination can serve as potential biomarkers of pregnancy outcome.

The present study was conducted to determine the patterns of free carnitine (FC) and AC esters in serum and FF in women undergoing IVF. Attempts were also made to assess the properties of blood-follicular barrier by quantifying simultaneously the short-, medium- and long-chain ACs in the two distinct fluid compartments. In addition, composition of carnitine pools was related to indices of reproductive potential such as number of oocytes and that of viable embryos.

Methods

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Pécs. Signed informed consent was obtained from all patients who participated in the study. The investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

Our case–control study was performed between March 24, 2011 and May 9, 2011 in the Assisted Reproduction Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Pécs, Hungary. In this period we performed 44 unselected IVF cycles, in 42 cases we made transvaginal ultrasound guided aspiration of FF. In the remaining 2 cycles the stimulation was unsuccessful. The patients were aged 23–40 years (mean: 32.3±5.1 years) and had BMI of 17.3-34.7 (mean: 23.80±4.9).

The patients were recruited into this study according to the date of the procedure, so it was an unselected population. They presented with the following main infertility diagnosis: male factors (14, 33.3%), damaged or blocked Fallopian tubes (10, 23.8%), severe endometriosis (7, 16.7%) and unexplained infertility (11, 26.2%). These latter patients experienced six unsuccessful intrauterine inseminations previously.

Among the patients there were no diabetes mellitus (type I and II), or reduced glucose tolerance.

Superovulation treatment was started after the necessary examinations, such as cervical smear, serum hormone measurements (follicular stimulating and luteinizing hormones /FSH, LH/, prolactin, estradiol, progesterone, testosterone, thyroid-stimulating hormone) on the 3rd and 21st days of the unstimulated cycles, human immune-deficiency virus and hepatitis-B surface antigen screening, hysteroscopy and andrologic examination. Patient enrollment into IVF procedure was approved by two independent physicians.

Control patients

During the study period samples were also obtained from 18 healthy women aged 25–40 years (mean: 33.4±5.2 years) and had BMI of 19.4-32.6 (mean: 25.01±4.7) admitted for minor elective surgery to serve as control for plasma carnitine profile.

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation

Inducing IVF GnRh agonist triptorelin (Gonapeptyl; Ferring®, Germany) was used in a long or short protocol, and the stimulation was performed with individual dosages of rFSH (Gonal-F; Serono® Aubonne, Switzerland), varying from 100 to 225 IU per day depending on the follicular maturation. The starting dose was adapted according to the BMI and the age. For patients with a previously known low response it was increased to a maximum dose of 300–350 IU daily. The follicular maturation was determined by ultrasound examination from the 6th day of the cycle, every other day. We changed the amount of the administered gonadotropins individually according to the size of the follicles. Ovulation was induced by injection of 250 μg of hCG (Ovitrelle; Serono®Aubonne, Switzerland) when at least two follicles exceeded 17 mm in diameter, and aspiration of FF was performed 36 hours later by ultrasonography-guided transvaginal puncture under routine intravenous sedation.

Collection of follicular fluid

The oocyte collection was performed using Sonoace 6000C two dimensional real time ultrasound scanner equipped with 4–8 MHz endovaginal transducer. The oocyte collection was performed in G-MOPS™ medium (Vitrolife, Göteborg, Sweden).

FF from individual follicles was aspirated and after collecting the oocytes the fluid was centrifuged for 10 min at 1500 r.p.m. and the supernatants were frozen and stored at −70°C for future analysis.

Fertilization methods

We performed the fertilization with intracytoplasmatic sperm injection (ICSI) depending on the andrological status (sperm count less than 15M/ml), the maternal age (> 35) and the number of the previous IVF cycles the patient had before (>2). The oocytes selected for ICSI were denuded with hyaluronidase and were assessed for maturity. Only metaphase II oocytes, identified by the presence of the first polar body, were chosen for fertilization. ICSI was performed 3–6 h after oocyte recovery in the medium G-MOPS™. The remained oocytes were fertilized with the conventional IVF method in a bicarbonate buffered medium (G-IVF™, Vitrolife®, Göteborg, Sweden). Fertilization was assessed 24 hours later in the medium G-1™ v5 (Vitrolife®, Göteborg, Sweden), the presence of two pronucleus signed the fertilization.

Embryo transfers were done 3–5 days after the oocyte retrieval. From day 3 to blastocyst stage we use the medium G-2™v5 (Vitrolife®, Göteborg, Sweden). According to the patient request we transferred one, two or three embryos. Cryopreservation of the remaining embryos was performed at this stage according to the Hungarian law. Progestogen supplementation was provided using 300 mg of progesterone 3 times a day (Utrogestan; Lab.Besins International S.A.®, Paris, France).

To evaluate the success of the treatment transvaginal ultrasound examination was performed 21 days after the embryo transfer to detect gestational sac.

Measurements of FC and ACs

FC and all the ACs were determined by butyl-ester forms using isotope dilution mass spectrometry (MS) method in a Micromass Quattro Ultima (Manchester, UK) ESI triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled with a Waters 2795 HPLC (Milford, MA, USA) system for sample introduction. For sample preparation 10 μl of serum or FF was used and a previously described procedure was followed [25]. During the ESI/MS/MS analysis FC and ACs were measured by positive precursor ion scan of m/z 85, with a scan range of m/z: 200?550. The applied capillary voltage, cone voltage and collision energy were 2.54 kV, 55 V and 26 eV, respectively.

Our mass spectrometry facility is a registered participant in the International Newborn Screening Quality Assurance Program organized by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, USA [26].

Routine hormone measurements were performed by using commercially available immunoassay kits. FSH and LH were measured with the electrochemiluminescent assay of Roche Ltd. (Elecsys 2010), while beta-HCG was measured with radioimmunoassay (Laborexpert, Hungary).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normality of data was evaluated by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Variables are presented as median and interquartile range. Differences in carnitine ester concentrations between patient and control groups were analysed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. If changes were found to be significant, Mann–Whitney U test were performed. Data binning was applied in the case of oocyte and embryo number. This process is a data pre-processing technique used to reduce the effects of minor observation errors. Optimal binning thresholds, resulting into harmonic groups were offered by the statistical program. For correlation analysis between serum and follicular fluid values, the non-parametric Spearman’s bivariate test was used. A difference of p<0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Carnitine profile measurements

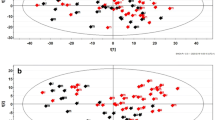

Serum and FF FC, individual and total ACs, as well as total carnitine concentrations of patients undergoing IVF are given in Table 1. For comparison the respective serum carnitine values for healthy control women was also presented. In the control group no follicular samples were available. As shown 20 distinct AC esters were detected in the serum and FF samples and there were no significant differences in serum carnitine levels between healthy subjects and IVF patients. However, analysis of FF carnitines revealed, that only the free and short-chain ACs were similar to those in maternal serum and the levels of medium-chain and long-chain AC ester levels were markedly lower. Accordingly, the serum to FF ratio of individual carnitine compounds increased progressively as the carbon chain length of carnitine esters increased (Figures 1 and 2). When FF carnitine profile was studied as a function of corresponding serum carnitines, a strong positive correlation was found between the two variables irrespective of their carbon chain length. Thus, serum free carnitine, total ACs, total carnitine, and total-, short-, medium- and long-chain ACs correlate highly significantly with the respective carnitine values in FF. Analysis of individual ACs, revealed that serum levels of C5-OH (short-chain), C12:1 (medium-chain) and C14, C14:1, C16 and C18 (long-chain) do not correlate with those in FF (Table 2). These observations suggest that FF carnitines mostly derive from plasma filtrate and AC esters with shorter carbon chain length more readily cross the blood/ovarian barrier than ACs with longer chain length.

Carnitine profile and reproductive potential

The association of serum and FF carnitine status with the number oocytes in IVF patients is shown in Table 3. It can be seen that serum FC fraction decreased significantly (p<0.05), and there was a general tendency to decrease for each, the short-, the medium-, and long-chain ACs in patients with binned oocyte number in patients where 9 or more oocyte were collected. Of the long- chain ACs the decrease of C14:1 fraction also proved to be significant (p<0.05).

Similar pattern of distribution was observed for FF carnitine compounds. In patients with oocytes of 9 or more FC (p<0.05) and short-chain ACs (p<0.05) were significantly reduced, whereas the reduction of total medium-chain and total long-chain ACs did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4 compares serum and FF concentrations of FC and major ACs in IVF patients with binned embryo number of 6 or less embryo developed with those patients where more than 6 embryo developed. Higher embryo number is associated with significantly depressed FC (p<0.05) and total serum carnitines (p<0.05), albeit the decrease of ACs is insignificant (p<0.10), it appears to be consistent. These findings are mirrored in the carnitine profile of FF where in addition to the significant decrease of FC (P<0.05), ACs of various carbon chain length decreased moderately but unanimously in patients with embryo number of more than 6.

Discussion

The present study provided evidences that serum carnitine profile of patients undergoing IVF is comparable to that of healthy women. FC and major AC esters can be detected in the FF, and the serum to FF ratio of individual carnitine compounds is inversely related to the carbon chain length of carnitine esters. Moreover, markers of reproductive potential (number of oocytes and embryos) appeared to be associated with reduction of FC and some individual ACs both in serum and FF.

In recent years considerable efforts have been made to identify potential biomarkers in FF to predict IVF outcome. FF serves as dynamic, physiological environment of maturing oocytes and embryos, therefore, it is assumed to reflect metabolic changes that occur during maturation. It has been shown to contain hormones, growth factors, reactive oxygen species, cytokines, apoptotic factors and several metabolic intermediates [27, 28]. Targeted analysis of specific biomarkers or certain combination of biomarkers has revealed important correlation with oocyte quality and/or related embryo.

The recent introduction of metabolomic and proteomic profiling of FF demonstrated that combined use of a panel of biomarkers as opposed to a single biomarker proved to be a reliable estimate of pregnancy outcome [29–32].

Our present study was prompted by the observations that L-carnitine-mediated β-oxidation of fatty acids is an essential energy source for oocyte and embryo development [5–8]. In this regard Dunning et al. reported that inhibition of carnitine palmitoyl transferase I (CPT I), the enzyme that catalyzes the initial step of β-oxidation, with etomoxir impaired subsequent embryo development. On the other hand, upregulation of β-oxidation during oocyte maturation by L-carnitine increased oocyte developmental competence as manifested by the increased rate of cleavage to 2-cell stage [21]. It was also demonstrated by the same group that L-carnitine supplementation during in vitro 3D follicle culture significantly increased β-oxidation and markedly improved both fertilization rate and blastocyst development without altering survival, growth or differentiation of follicles [22]. The beneficial effect of L-carnitine on reproductive performance has been well- documented, it has been claimed, however, that in addition to its essential role in β-oxidation l-carnitine has the capacity to protect against oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis [20, 23, 24, 33]. L-carnitine-related improvement of insulin resistance and glucose utilization may also contribute to the better IVF outcome [34]. However several animal studies investigated the impact of L-carnitine supplementation on oocyte quality and preimplantation embryo development [22–24, 35–37], very limited data are accessible for the carnitine levels of human ovarian follicular samples [38, 39] and no reports are available on their acylcarnitine profiles. In their study Montjean et al. could not observe correlations between the total carnitine content of the follicular fluid and either the circulating estradiol content of the serum or the outcome of the IVF attempt. Robker et al. investigated the L-carnitine concentrations in follicular fluid samples from women who were administered human chorionic gonadotropin. It is not known whether the L-carnitine level is regulated during the menstrual cycle by gonadotropin [38]. In our study in an attempt to further explore the relationship between IVF parameters and the composition of endogenous carnitine pool we determined the concentrations of FC and 20 major AC esters in serum and FF samples obtained from patients receiving IVF. Importantly, all individual ACs measured could be detected in FF, their concentrations, however, proved to be dependent on maternal serum concentrations and on the carbon chain length of acyl groups. These findings are consistent with the notion that FC and AC esters cross the blood-follicular barrier but the passage through this barrier is reduced as molecular weight and lipophilicity increases with the increasing carbon chain length. Moreover, serum and FF carnitine profiling revealed marked reduction in total carnitine, FC and AC levels in IVF patients with oocyte number of >9 and/or with embryo number of >6 as compared to those with the respective values of <9 and/or <6. Based on these results we suggest that the L-carnitine/AC pathway is upregulated and the actual carnitine pool is depleted in patients with better reproductive potential.

Mitochondrial transport of long-chain fatty acids for β-oxidation is achieved via the carnitine circle. This requires the consecutive action of CPT I, carnitine-AC translocase, and CPT II [40, 41]. The coordinated increase in the activity of these enzymes may result in enhanced transfer of activated long-chain fatty acids across the mitochondrial membranes and in an increase of substrate availability for β-oxidation to meet the greater energy requirements of IVF patients with better developmental performance. It is conceivable that this accelerated process consumes excess carnitine and deprives carnitine pools.

While our study underlines the importance of carnitine-mediated β-oxidation in reproduction it is to be considered that women with disrupted carnitine cycle can conceive and proceed to successful pregnancy. Indeed, there are case reports of patients with adult-onset CPT II deficiency who become pregnant and went on to deliver preterm or full-term newborns [42–45]. In order to identify IVF patients at risk of functional L-carnitine deficiency further studies are to be conducted to measure simultaneously carnitine compounds and markers of free fatty acid metabolism.

Conclusions

Carnitine profiling of women undergoing IVF provided suggestive evidences that L-carnitine metabolism is accelerated and the developmental competence of oocytes and early embryos can be optimalized by giving supplemental L-carnitine.

Abbreviations

- AC:

-

Acylcarnitine

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CPT:

-

Carnitine palmitoyl transferase

- FC:

-

Free carnitine

- FF:

-

Follicular fluid

- FSH:

-

Follicular stimulating hormone

- hCG:

-

Human choriogonadotropin

- ICSI:

-

Intracytoplasmatic sperm injection

- IVF:

-

In vitro fertilization

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone.

References

Biggers JD, Whittingham DG, Donahue RP: The pattern of energy metabolism in the mouse oocyte and zygote. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967, 58: 560-567. 10.1073/pnas.58.2.560.

Van Blerkom JU, Davis PW, Lee J: ATP content of human oocytes and developmental potential and outcome after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 1995, 10: 415-424.

Nagano M, Katagiri S, Takahashi Y: ATP content and maturational/developmental ability of bovine oocytes with various cytoplasmic morphologies. Zygote. 2006, 14: 299-304. 10.1017/S0967199406003807.

Thompson JG, Lane M, Gilchrist RB: Metabolism of the bovine cumulus-oocyte complex and influence on subsequent developmental competence. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2007, 64: 179-190.

Hillman N, Flynn TJ: The metabolism of endogenous fatty acids by preimplantation mouse embryos developing in vitro. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1980, 56: 157-168.

Downs SM, Mosey JL, Klinger J: Fatty acid oxidation and meiotic resumption in mouse oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009, 76: 844-853. 10.1002/mrd.21047.

Sturmey RG, Reis A, Leese HJ, McEvoy TG: Role of fatty acids in energy provision during oocyte maturation and early embryo development. Reprod Domest Anim. 2009, 44: 50-58.

McKeegan PJ, Sturmey RG: The role of fatty acids in oocyte and early embryo development. Reprod Fert Develop. 2011, 24: 59-67.

Matorras R, Ruiz JI, Mendoza R, Ruiz N, Sanjurjo P, Rodriguez-Escudero FJ: Fatty acid composition of fertilization-failed human oocytes. Human Reprod 1998, 13:2227–2230. Br J Nutr. 2007, 98: 345-350. 10.1017/S0007114507705020.

Leroy JLMR, Vanholder T, Mateusen B, Christophe A, Opsomer G, de Kruif A, Genicot G, Van Soom A: Non-esterified fatty acids in AC of dairy cows and their effect on developmental capacity of bovine oocytes in vitro. Reproduction. 2005, 130: 485-495. 10.1530/rep.1.00735.

Van Hoeck V, Sturmey RG, Bermejo-Alvarez P, Rizos D, Gutierrez-Adan A, Leese HJ, Bois PEJ, Leroy JLMR: Elevated non-esterified fatty acid concentrations during bovine oocyte maturation compromise early embryo physiology. PLoS ONE. 2011, 6: e23183-10.1371/journal.pone.0023183.

Melegh B, Sumegi B, Sherry AD: Preferential elimination of pivalate with supplemental carnitine via formation of pivaloylcarnitine in man. Xenobiotica. 1993, 23: 1255-1261. 10.3109/00498259309059436.

Melegh B, Pap M, Morava E, Molnar D, Dani M, Kurucz J: Carnitine-dependent changes of metabolic fuel consumption during long-term treatment with valproic acid. J Pediatr. 1994, 125: 317-321. 10.1016/S0022-3476(94)70218-7.

Melegh B, Kerner J, Acsadi G, Lakatos J, Sandor A: L-carnitine replacement therapy in chronic valproate treatment. Neuropediatrics. 1990, 21: 40-43. 10.1055/s-2008-1071456.

Vaz FM, Melegh B, Bene J, Cuebas D, Gage DA, Bootsma A, Vreken P, van Gennip AH, Bieber LL, Wanders RJ: Analysis of carnitine biosynthesis metabolites in urine by HPLC-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2002, 48: 826-834.

Melegh B, Kerner J, Sandor A, Vinceller M, Kispal G: Effects of oral L-carnitine supplementation in low-birth-weight premature infants maintained on human milk. Biol Neonate. 1987, 51: 185-193. 10.1159/000242650.

Kispal G, Melegh B, Alkonyi I, Sandor A: Enhanced uptake of carnitine by perfused rat liver following starvation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987, 896: 96-102. 10.1016/0005-2736(87)90360-9.

Hoppel C: The role of carnitine in normal and altered fatty acid metabolism. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003, 41 (Suppl 4): S4-S12.

Bremer J: Carnitine metabolism and function. Physiol Rev. 1983, 63: 1420-1480.

Mansour G, Abdelrazik H, Sharma RK, Radwan E, Falcone T, Argarwal A: L-carnitine supplementation reduces oocyte cytoskeleton damage and embryo apoptosis induced by incubation in peritoneal fluid from patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009, 91: 2079-2086. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.097.

Dunning KR, Cashman K, Russell DL, Thompson JG, Norman RJ, Robker RL: Beta-oxidation is essential for mouse oocyte developmental competence and early embryo development. Biol Reprod. 2010, 83: 909-918. 10.1095/biolreprod.110.084145.

Dunning KR, Akison LK, Russel DL, Norman RJ, Robker RL: Increased beta-oxidation and improved oocyte developmental competence in response to l-carnitine during ovarian in vitro follicle development in mice. Biol Reprod. 2011, 85: 548-555. 10.1095/biolreprod.110.090415.

Wu G-Q, Jia B-Y, Li JJ, Fu X-W, Zhou G-B, Hou Y-P, Zhu S-E: L-carnitine enhances oocyte maturation and development of parthenogenetic embryos in pigs. Theriogenol. 2011, 76: 785-793. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.04.011.

Somfai T, Kaneda M, Akagi S, Watanabe S, Haraguchi S, Mizutanie E, Dang-Nguyen TQ, Geshi M, Kikuchi K, Nagai T: Enhancement of lipid metabolism with l-carnitine during in vitro maturation improves nuclear maturation and cleavage ability of follicular porcine oocytes. Reprod Fertil Develop. 2011, 23: 912-920. 10.1071/RD10339.

Bene J, Komlósi K, Magyari L, Talian G, Horváth K, Gasztonyi B, Miheller P, Figler M, Mózsik G, Tulassay Z, Melegh B: Plasma carnitine ester profiles in Crohn’s disease patients characterized for SLC22A4 C1672T and SLC 22A5 G-207C genotypes. Br J Nutr. 2007, 98 (2): 345-50. 10.1017/S0007114507705020.

Centers for disease control and prevention, Newborn screening Quality assurance program. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nsqap/Public/default.aspx

Baka S, Malamitsi-Puchner A: Novel follicular fluid factors influencing oocyte developmental potential in IVF: a review. Reprod BioMed online. 2006, 12: 500-506. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)62005-6.

Revelli A, Piane LD, Casano S, Molinari E, Massobrio M, Rinaudo P: Follicular fluid content and oocyte quality¨from single biochemical markers to metabolomics. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009, 7: 40-10.1186/1477-7827-7-40.

Seli E, Botros L, Sakkas D, Burns DH: Noninvasive metabolomic profiling of embryo culture media using proton nuclear magnetic resonance correlates with reproductive potential of embryos in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2008, 90: 2183-2189. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.1739.

Estes SJ, Ye B, Qiu W, Cramer D, Hornstein MD, Missmer SA: A proteomic analysis of IVF follicular fluid in women < 32 years old. Fertil Steril. 2009, 92: 1569-1578. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.120.

Pinero-Sagredo E, Nunes S, De Los Santos MJ, Celda D, Esteve V: NMR metabolic profile of human follicular fluid. NMR Biomed. 2010, 23: 485-495. 10.1002/nbm.1488.

Wallace M, Cottell E, Gibney MJ, McAuliffe FM, Windfield M, Brennan L: An investigation into the relationship between the metabolic profile of follicular fluid, oocyte developmental potential, and implantation outcome. Fertil Steril. 2012, 97: 1078-1084. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.122.

Abdelrazik H, Sharma R, Mahfouz R, Agarwal A: L-carnitine decreases DNA damage and improves the in vitro blastocyst development rate in mouse embryos. Fertil Steril. 2009, 91: 589-596. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.067.

Mingrone G, Greco AV, Capristo E, Benedetti G, Giancaterini A, DeGaetano A, Gasbarrini G: L-carnitine improves glucose disposal in type 2 diabetic patients. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999, 18: 77-82. 10.1080/07315724.1999.10718830.

Phongnimitr T, Liang Y, Srirattana K, Panyawai K, Sripunya N, Treetampinich C, Parnpai R: Effect of L-carnitine on maturation, cryo-tolerance and embryo developmental competence of bovine oocytes. Anim Sci J. 2013, 10.1111/asj.12067. [Epub ahead of print]

Moawad AR, Tan SL, Xu B, Chen HY, Taketo T: L-carnitine supplementation during vitrification of mouse oocytes at the germinal vesicle stage improves preimplantation development following maturation and fertilization in vitro. Biol Reprod. 2013, 88: 104-10.1095/biolreprod.112.107433.

Sutton-McDowall ML, Feil D, Robker RL, Thompson JG, Dunning KR: Utilization of endogenous fatty acid stores for energy production in bovine preimplantation embryos. Theriogenology. 2012, 77: 1632-1641. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.12.008.

Dunning KR, Robker RL: Promoting lipid utilization with l-carnitine to improve oocyte quality. Anim Reprod Sci. 2012, 134: 69-75. 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2012.08.013.

Montjean D, Entezami F, Lichtblau I, Belloc S, Gurgan T, Menezo Y: Carnitine content in the follicular fluid and expression of the enzymes involved in beta oxidation in oocytes and cumulus cells. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012, 29: 1221-1225. 10.1007/s10815-012-9855-2.

Ramsay RR, Gandour R, van der Leij FR: Molecular enzymology of carnitine transfer and transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001, 1546: 21-43. 10.1016/S0167-4838(01)00147-9.

Longo N, Amat di SanFilippo C, Pasquali M: Disorders of carnitine transport and the carnitine cycle. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006, 142C: 77-85. 10.1002/ajmg.c.30087.

Dreval D, Bernstein D, Zakut H: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase deficiency in pregnancy – a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994, 170: 1390-1392. 10.1016/S0002-9378(94)70168-7.

Lilker S, Kasodekar S, Goldszmith E: Anesthetic management of a parturient with carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency. Can J Anaesth. 2006, 53: 482-486. 10.1007/BF03022621.

Ramsey PS, Biggio JR: Carnitine palmitoyltransferase deficiency in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonat Med. 2005, 18: 357-359. 10.1080/14767050500275861.

Hull ML, Nemeth D, Hague WM, Wilkinson C, Liebelt J, Lane M, Feil D, Hons BS: Mitochondrial fatty acid transport enzyme deficiency – implications for in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2009, 91 (2732): 11-14.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by OTKA: T73430. The authors are grateful for Marta Hartung for her help in the technical management of the study. The work was supported by: SROP-4.2.2.A-11/1/KONV-2012-0053 Investigation of biomarkers in culture medium influencing on the success rate of in vitro fertilization

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare, that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

ÁV: Participated in designing the study, contributed to sample collection and critical discussion and drafted the manuscript. JB: Participated in designing the study, laboratory measurements and drafted the manuscript. ES: Conceived the study, participated in its design and critical discussion and drafted the manuscript. GLK: Contributed to data interpretation and statistical analysis. JB: Supervised the clinical part of the study, drafting the manuscript. BM: Supervised the laboratory part of the study, assisted with drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ákos Várnagy, Judit Bene, József Bódis and Béla Melegh contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Várnagy, Á., Bene, J., Sulyok, E. et al. Acylcarnitine esters profiling of serum and follicular fluid in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 11, 67 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-11-67

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-11-67