Abstract

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) are rare soft-tissue tumors with an extremely heterogeneous clinical behavior. They may arise in different organs and may behave indolently or sometimes metastasize with different grades of biological aggressiveness. We report the case of a young woman with a primary inoperable PEComa of the liver with malignant histological features. Since the mTOR pathway is often altered in PEComas and responses have been reported with mTOR-inhibitors such as sirolimus or temsirolimus, we decided to start a neoadjuvant treatment with sirolimus. The patient tolerated the treatment fairly well and after 8 months a favorable tumor shrinkage was obtained. The patient then stopped sirolimus and 2 weeks later underwent partial liver resection, with complete clinical recovery and normal liver function. The histological report confirmed a malignant PEComa with vascular invasion and negative margins. Then 6 additional months of post-operative sirolimus treatment were administered, followed by regular radiological follow-up. For patients with a large and histologically aggressive PEComa, we think that neoadjuvant treatment with mTOR-inhibitor sirolimus may be considered to facilitate surgery and allow early control of a potentially metastatic disease. For selected high-risk patients, the option of adjuvant treatment may be discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sarcomas are a heterogeneous, rare and complex group of mesenchymal tumors, which can occur at any age and in any part of the body. Rarity of the disease, heterogeneity of the site, grade and histology have been the major determinants for the controversial results obtained in clinical studies conducted so far in the management of localized sarcomas [1].

The term perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) was first introduced by Zamboni et al. [2] to describe a family of soft-tissue tumors characterized by melanocytic and smooth muscle differentiation that may arise in different organs and are considered ubiquitous tumors. The distinctive feature of PEComa is the perivascular epithelioid cell, a mesenchymal cell type frequently seen adjacent to blood vessels. The so-called PEComa family of tumors encompasses additional clinical entities such as angiomyolipoma, clear-cell sugar tumors of the lung, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and unusual clear-cell tumors of various organs [3]. Their biological behavior is extremely heterogeneous, ranging from indolent and benign forms to aggressive tumors with malignant transformation and metastatic potential [4].

Due to the rarity and different sites of presentation, the management of these tumors is still a matter of debate in terms of the timing of surgery and the need formultimodal treatments. Here we report the case of a young woman with a primitive PEComa of the liver who underwent radical resection after neoadjuvant treatment with sirolimus.

Case presentation

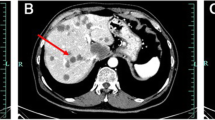

A 31-year-old woman was first referred to our institution in January 2012 because vomiting and gastric reflux had prompted a liver echography and a large hepatic mass had been found. The patient was on an antidepressant drug (ziprasidone) plus lansoprazole. She underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which showed a voluminous, richly vascularized mass occupying the right lobe of the liver (Figure 1a). The biopsy showed sheets of large epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and pleomorphic nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Scattered multinuclear giant cells were present. Mitotic activity was 4/50 high power fields (HPF) and tumor necrosis was not observed (Figure 2). Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were strongly positive for MelanA and microphthalmia transcription factor (MIFT), and focally positive for HMB-45, desmin and smooth muscle actin. Lymphovascular invasion was found in the specimen. A diagnosis of epithelioid angiomyolipoma with high-grade cellular atypia (epithelioid PEComa with malignant potential) was therefore made, according to the criteria proposed by Folpe and Kwiatkowski [4].

A total body computed tomography scan excluded the presence of extra-hepatic disease and hematology, renal and liver function tests were normal. Our gastrointestinal Multidisciplinary Team discussed surgical options but in consideration of the volume of the disease, very close to hepatic veins, we decided to postpone surgery and consider neoadjuvant treatment. PEComas are usually considered chemoresistant tumors, but published reports of responses obtained with the mTOR-inhibitors sirolimus and temsirolimus [5–9] provided the rationale for the use of an agent of this class.

Two months later the patient started therapy with oral sirolimus 2 mg per day continuatively, as compassionate use authorized by the local Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico of Istituto Oncologico Veneto (Padova, Italy)). In the absence of toxicity at day 15, the dose was increased to 3 mg per day. Her sirolimus plasma concentration was regularly checked due to the risk that liver involvement by the tumor and concomitant medications could alter drug clearance. Trough values were in the range from 12.6 to 20.1 μg/l, and therefore within therapeutic range. Over the following weeks the patient experienced gastrointestinal toxicity (diarrhea and gastric reflux, grade 2 according to CTCAE), and so loperamide and analgesics were administered and there were a few short treatment interruptions.

After 3 months, an MRI scan demonstrated a partial response of the mass, with colliquation of its inner part and a reduction of the internal vascularization. Thus, sirolimus was continued at the same dosage for another 5 months, when a new radiological assessment showed further shrinkage of the tumor (Figure 1b).

After a multidisciplinary discussion confirmed resectability of the mass, the patient stopped taking sirolimus and 2 weeks later underwent resection of segments IVb, V and VI. The surgical procedure was carried out free of complications, with full recovery. All surgical margins were negative at the final histological examination, which confirmed malignant PEComa with vascular invasion.

The presence of intravascular tumor cells is a strongly adverse prognostic factor for relapse of breast, colon and other types of tumors, while its role in sarcomas is not universally recognized [10]. However, in consideration of the size and the malignant features of this tumor, as well as fairly good tolerability of the drug, we decided to administer 6 additional months of sirolimus as post-operative treatment, still ongoing at the time of this writing.

Discussion

The definition of perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasia or PEComa encompasses several types of tumors including angiomyolipoma, clear-cell sugar tumors of the lung, lymphangioleiomyomatosis and unusual clear-cell tumors occurring in the kidney, pancreas, uterus or liver, among others [3]. The majority of PEComas arise in women, with a median age of 38 years [6]. They may arise in different anatomical sites, even if they seem to occur with more frequency in the retroperitoneum, abdominal cavity and other viscera such as the gastrointestinal tract, pelvis and liver [3, 4].

PEComas are generally benign tumors, and usually do not recur after surgical resection; however, a subgroup of PEComas exhibits a combination of infiltrative growth, atypical mitotic figures, high mitotic index and marked hypercellularity. These lesions have a malignant behavior, with either local recurrence or metastatic spread, commonly in the lungs. Folpe and Kwiatkowski [4] reported an association between malignant clinical behavior and a tumor size greater than 5 cm, histological infiltrative pattern, more than 1 mitosis/50 HPF and a high nuclear grade.

PEComas may be associated with the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant neurocutaneous disorder caused by genetic alterations of the TSC1 (9q34) or TSC2 (16p13.3) genes [11], and characterized by mental retardation, seizures and multiple tumors in different sites [12]. The role of the TSC genes in the pathogenesis of sporadic PEComa has still to be elucidated, but recent data suggest that small deletions or mutations (inactivating or missense) in genes TSC1 or TSC2 may account for loss of TSC2 expression in those tumors [5, 13]. For a series of 15 PEComas, Kenerson et al. [14] reported the immunohistochemical evidence of mTORC1 activity, which suggests loss of TSC1 or TSC2. The loss of heterozygosity in the TSC1 or TSC2 region has also been reported in seven cases of PEComa by Pan et al. [15]. These data support inhibition of mTOR as a rational strategy for treating tumors occurring in TSC or those harboring TSC-related mutations.

Due to its rarity, data on medical treatment for PEComas originate from small case series, most of which employed the mTOR-inhibitor sirolimus. Wagner et al. treated three patients with sirolimus, all of whom showed a radiographic responses [5]. Bissler et al. [7] described a program of 12 months of treatment followed by 12 months of observation for angiomyolipoma, reporting a 53% volume reduction during active therapy, but also 86% regrowth during the observation period. This experience underlines the role of continuative therapy to maintain tumor shrinkage. A case of facial angiofibroma associated with TSC and treated with sirolimus has been published [8]. One significant response has been reported with temsirolimus, an alternative mTOR inhibitor that requires weekly intravenous injections [9].

Our patient was diagnosed with a large and aggressive variant of a PEComa, which showed significant shrinkage after upfront treatment with sirolimus. This allowed radical removal of the mass without surgical complications or sequelae. The tolerability of this agent was fairly good although there were some short treatment breaks due to gastrointestinal toxicity. The sirolimus plasma concentration was regularly checked to ensure that any impairment of liver metabolism due to tumor involvement or interactions with concomitant medications (ziprasidone and analgesics) did not expose the patient to excessive drug concentrations.

Conclusion

This case is, to our knowledge, the first report of the use of neoadjuvant sirolimus for malignant PEComa achieving a significant impact on patient management and with a possibly curative potential. This confirms the importance of mTOR pathway inhibition in the treatment of these rare tumors. Tumors deemed inoperable or with borderline resectability may therefore be evaluated early for systemic neoadjuvant treatment with sirolimus to obtain tumor shrinkage and facilitate surgical removal. The option of adjuvant treatment may be considered for selected high-risk patients who can tolerate the mTOR inhibitor.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- HPF:

-

high power fields

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- PEComa:

-

perivascular epithelioid cell tumor

- TSC:

-

tuberous sclerosis complex.

References

Maruzzo M, Rastrelli M, Lumachi F, Zagonel V, Basso U: Adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas. Curr Med Chem. 2013, 20 (5): 613-620. 10.2174/092986713804999385.

Zamboni G, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zancanaro C, Faccioli G, Gilioli E, Pederzoli P, Bonetti F: Clear cell ‘sugar’tumor of the pancreas. A novel member of the family of lesions characterized by the presence of perivascular epithelioid cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996, 20 (6): 722-730. 10.1097/00000478-199606000-00010.

Folpe AL: Neoplasms with perivascular epithelioid cell differentiation (PEComas). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Edited by: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Epstein J, Mertens F. 2002, Lyon: IARC Press, 221-222. [WHO Classification of Tumours.]

Folpe AL, Kwiatkowski DJ: Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms: pathology and pathogenesis. Hum Pathol. 2010, 41 (1): 1-15. 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.05.011.

Wagner AJ, Malinowska-Kolodziej I, Morgan JA, Qin W, Fletcher CD, Vena N, Ligon AH, Antonescu CR, Ramaiya NH, Demetri GD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Maki RG: Clinical activity of mTOR inhibition with sirolimus in malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: targeting the pathogenic activation of mTORC1 in tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28 (5): 835-840. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2981.

Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW: Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005, 29: 1558-1575. 10.1097/01.pas.0000173232.22117.37.

BisslerJJ MCFX, Young LR, Elwing JM, Chuck G, Leonard JM, Schmithorst VJ, Laor T, Brody AS, Bean J, Salisbury S, Franz DN: Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358 (2): 140-151. 10.1056/NEJMoa063564.

Hofbauer GF, Marcollo-Pini A, Corsenca A, Kistler AD, French LE, Wüthrich RP, Serra AL: The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin significantly improves facial angiofibroma lesions in a patient with tuberous sclerosis. Br J Dermatol. 2008, 159 (2): 473-475. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08677.x.

Italiano A, Delcambre C, Hostein I, Cazeau AL, Marty M, Avril A, Coindre JM, Bui B: Treatment with the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus in patients with malignant PEComa. Ann Oncol. 2010, 21 (5): 1135-1137. 10.1093/annonc/mdq044.

Yudoh K, Kanamori M, Ohmori K, Yasuda T, Aoki M, Kimura T: Concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor in the tumour tissue as a prognostic factor of soft tissue sarcomas. Br J Cancer. 2001, 84 (12): 1610-1615. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1837.

van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, Nellist M, Janssen B, Verhoef S, Lindhout D, van den Ouweland A, Halley D, Young J, Burley M, Jeremiah S, Woodward K, Nahmias J, Fox M, Ekong R, Osborne J, Wolfe J, Povey S, Snell RG, Cheadle JP, Jones AC, Tachataki M, Ravine D, Sampson JR, Reeve MP, Richardson P, Wilmer F, Munro C, Hawkins TL: Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 1997, 277 (5327): 805-808. 10.1126/science.277.5327.805.

Bonetti F, Martignoni G, Colato C, Manfrin E, Gambacorta M, Faleri M, Bacchi C, Sin VC, Wong NL, Coady M, Chan JK: Abdominopelvic sarcoma of perivascular epithelioid cells. Report of four cases in young women, one with tuberous sclerosis. Mod Pathol. 2001, 14 (6): 563-568. 10.1038/modpathol.3880351.

Smolarek TA, Wessner LL, McCormack FX, Mylet JC, Menon AG, Henske EP: Evidence that lymphangiomyomatosis is caused by TSC2 mutations: chromosome 16p13 loss of heterozygosity in angiomyolipomas and lymph nodes from women with lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998, 62 (4): 810-815. 10.1086/301804.

Kenerson H, Folpe AL, Takayama TK, Yeung RS: Activation of the mTOR pathway in sporadic angiomyolipomas and other perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms. Hum Pathol. 2007, 38 (9): 1361-1371. 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.01.028.

Pan CC, Chung MY, Ng KF, Liu CY, Wang JS, Chai CY, Huang SH, Chen PC, Ho DM: Constant allelic alteration on chromosome 16p (TSC2 gene) in perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa): genetic evidence for the relationship of PEComa with angiomyolipoma. J Pathol. 2008, 214 (3): 387-393. 10.1002/path.2289.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pfizer- Italy for providing sirolimus as compassionate use.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

We declare no competing interests for all authors.

Authors’ contributions

FB, UB, VZ and UC made substantial contributions to conception, data acquisition and analysis and interpretation of results. FB, MM, MCM were involved in drafting the article. UB and EG revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergamo, F., Maruzzo, M., Basso, U. et al. Neoadjuvant sirolimus for a large hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa). World J Surg Onc 12, 46 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-46

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-46