Abstract

Background

Carcinosarcoma is a malignancy that rarely occurs in the renal pelvis.

Materials and methods

We present a case of histologically proven, native renal pelvis carcinosarcoma in a 65-year-old woman who had accepted a renal transplant. We performed a laparoscopic ureterectomy, combined with lymph node dissection and immunosuppression with sirolimus (SRL), which was alternated with the conventional immunosuppressant - cyclosporine.

Results

This patient was still alive 34 months after renal transplantation.

Conclusions

Operation is still the best choice, and the SRL may be beneficial for preventing the progression of a tumor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The overall incidence of de novo malignancies in renal transplant (RT) recipients is significantly higher than in the general population due to long-term immunosuppressive therapy and oncogenic viral infections [1, 2]. The malignant tumors of the transplanted kidney are mainly nonmelanoma skin cancers and malignancies, including post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder and solid organ cancer [3, 4]. The prevalence and characteristics of post-transplant malignancies differ in various geographic areas. In western countries, the most common type of post-transplant urinary tract malignancy is renal cell carcinoma [1]. In contrast, the majority of reported tumors in Chinese patients were urothelial carcinomas [5, 6], which occurred in 4.1% of all RT recipients and 47.6% of all patients with a post-transplant malignancy [6]. Carcinosarcoma of the kidney and renal pelvis (CSKP) commonly presented as high-grade, advanced stage disease, and was associated with a poor prognosis regardless of location [7].

Carcinosarcoma of the renal pelvis is an extremely rare malignancy with a poor prognosis in the few reported cases [8–11]. The carcinosarcoma of the renal pelvis in patients after renal transplantation is rarer. Here, we present a histologically proven case of carcinosarcoma of the left renal pelvis in renal transplant recipient.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old female patient developed chronic renal failure with unknown etiology and began hemodialysis in 2003. The patient denied past tobacco use or analgesic abuse. The patient received a renal transplantation in 2005 from a male cadaveric donor. Immunosuppressive therapy was applied using a triple immunosuppressive regimen, including cyclosporine (CsA), prednisone, and mycophenolate mofetil.

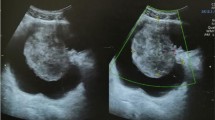

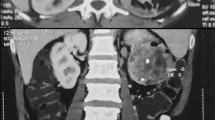

The patient suffered from a pulmonary cytomegalovirus infection 8 months after the renal transplantation, and took oral cyclosporine and prednisone for a combination immunosuppressive treatment after the transplant. She had normal renal function, and the serum creatinine levels were maintained at 0.62 to 0.88 mg/dL. Forty-eight months after the renal transplantation, the patient went to the local hospital because of recurrent gross hematuria with waist pain on the left side. The CT examination revealed a left pelvic lesion of approximately 5 cm × 4 cm (Figure 1). It was showed in the CT image that, irregular nodular soft tissue shadow filled in the left pelvis; the adjacent calyces and renal parenchyma were compressed; and there was no obvious swollen lymph gland shadow. Preoperative cystoscopy and chest computed tomography (CT) examinations revealed no abnormalities.

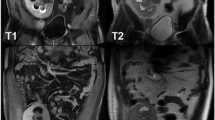

A pathological examination showed that the size of the full-cut kidney and the surrounding fat capsule was 15 cm × 10 cm × 5 cm, and the actual kidney size was 12 cm × 7 cm × 4 cm. A bulging mass of 6 cm × 4 cm was observed at the renal pelvic cut surface without an envelope. This mass showed infiltrative growth that was gray and of fine quality, partly translucent and jelly-like, and also showed some hemorrhagic and necrotic areas. The renal parenchyma was atrophied and the ureteral length was 8 cm. Microscopic observations revealed two tumor components. One was a high-grade urothelial carcinoma component with partial papillary arrangement, and the epithelial cells were mostly heterotypic and pleomorphic, with some of them falling off. The cell nucleus was obviously pleomorphic, deeply stained, and the nucleolus was prominent and visible with pathological mitotic figures. The other was a heterologous sarcomatous component with a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) structure, and this was the dominant component. The tumors showed a diffuse growth or formed an alternate distribution of cell-rich areas and cell-sparse areas. The sparse areas were associated with myxoid stroma. The blood vessels were surrounded by tumor cells. The cells were fusiform and polygonal, and the cytoplasm was abundant, with red staining. The nucleus was large, deeply stained and irregular, and the nucleolus was prominent, with visible mitotic figures, multifocal necrosis and hemorrhage. Part of the region showed urothelial carcinoma and MPNST component with a transitional phase (Figure 2). According to the TNM classification system, the patient was diagnosed with stage pT3N0M0.

An immunohistochemical examination showed that cytokeratin of the urothelial carcinoma was positive (Figure 3). Vimentin was positive in the sarcoma, and was negative in the urothelial carcinoma (Figure 4). Some of the MPNST cells S-100 were positive in the carcinoma and sarcoma transition area, and strongly positive in the area of the sarcoma cells (Figure 5). Smooth muscle actin (SMA) of sarcoma cells was negative, and Human Melanoma Black (HMB45) and desmin were negative.

The pathological diagnosis was that the left renal pelvic carcinosarcoma invaded the renal parenchyma, but was not involved the ureteral stump.

The patient accepted laparoscopic ureterectomy combined with lymph node dissection in our hospital. The operation went well, and 7 days after the operation, she was discharged from the hospital as she had recuperated. One week after the operation, she began to adjust the immunosuppressive regimen by using sirolimus (SRL) instead of cyclosporine, and the initial loading dose of SRL was 2 mg and 1 mg the next day, which was taken 4 hours after meals. Regular monitoring of blood concentrations was carried out after the conversion, and the drug dosage was adjusted according to the blood concentration, to maintain a plasma concentration of 4 to 6 μg/L of SRL. The patient refused to undergo any adjuvant therapy after the operation. She accepted regular postoperative follow-up. At the time of writing, 34 months after the left kidney ureterectomy, she is still alive with normal renal function.

Discussion

The overall incidence of de novo malignancies after RT is four to five times higher than that in the general population and has been estimated to be as high as 20% after 10 years [1]. According to the Cincinnati Transplant Tumor Registry, the most prevalent de novo neoplasms in organ transplant recipients are skin cancers and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease [1, 2]. For urinary tract, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) was the most frequent tumor after RT in the west [1, 5], with urothelium cancer being most frequent in China [6]. The development of carcinosarcoma is well documented in the mammary gland, the larynx and the uterus. Less frequently, development in bladder, esophageal, lung and kidney has been reported. Fewer than twenty cases of carcinosarcoma of the pelvis have been described in the literature.

Carcinosarcoma is often difficult to distinguish from sarcomatoid carcinoma. Carcinosarcomas are composed of epithelial and sarcomatous components, and sarcomatoid carcinomas are malignant spindle cell neoplasms composed of epithelial components containing changes of sarcomatoid morphology [12]. Microscopically, the carcinomatous component is mostly transitional cell carcinoma and the sarcomatous component is largely composed of spindle or pleomorphic tumor giant-cells. Carcinosarcomas and sarcomatoid carcinomas are similar on hematoxylineosin staining, so immunohistochemical study is mandatory for diagnosis. In this case, epithelial component expressed cytokeratins while sarcomatous component vimentin and S-100. The pathological diagnosis is confirmed.

Exact survival rate remains a matter of controversy due to a lack of consistent long-term follow-up. Wang et al. reviewed the carcinosarcoma involving kidney and renal pelvis, and the median cancer specific survival was 6 months and the 1-year cancer specific survival rate for the entire cohort was 30.2% [7]. In the present report, this patient is still alive (>34 months) with normal renal function and no metastasis. This survival may be because regular follow-up allowed for diagnosis and treatment of the tumor in an early stage and because SRL instead of cyclosporine may have suppressed the progression of tumor. Hojo et al. has reported that cyclosporine can promote cancer progression by a direct cellular effect that is independent of its effect on the host’s immune cells, and that cyclosporine-induced transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) production is involved in this [13]. That is to say, cyclosporine can also promote cancer progression directly. As is reported, when compared with cyclosporine, SRL induce adverse events more frequently, but the mean MDRD eGFR is higher for renal function [14]. The reintroduction of calcineurin inhibitors is safe in patients who have been withdrawn from sirolimus owing to adverse effects [15]. SRL, besides its antiangiogenic properties, has a strong tumor-specific functional effect on established tumor vessels [16].

Carcinosarcoma is rare in renal pelvis but progresses rapidly and has an unsatisfactory prognosis. The pathologic stage is the main predictor of patient survival. No direct correlation has been found with previous stone disease, infection, or radiation exposure and tumor development. Chemotherapy offers little response and no survival advantage [17–20]. Treatment is early nephrectomy. For this, early diagnosis should be made. Transplanted and native kidneys should be screened for tumors by ultrasound after transplantation [21]. Thus, tumors can be diagnosed at an early stage. RT recipients should do ultrasound and CT in regular postoperative follow-ups to allow for the diagnosis of carcinosarcoma at an early stage. Nonfunctioning native kidneys with suspicious lesions should be removed early [5].

Conclusion

In conclusion, carcinosarcoma is rare in the renal pelvis, progresses rapidly and has an unsatisfactory prognosis. It is not sensitive to chemo-radiation. Operation is still the best choice, and the SRL may be beneficial for preventing the progression of the tumor. From a therapeutic and prognostic point of view, it is important to make a correct and early diagnosis.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CsA:

-

cyclosporine

- CSKP:

-

carcinosarcoma of the kidney and renal pelvis

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- MPNST:

-

malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

- RCC:

-

renal cell carcinoma

- RT:

-

renal transplant

- SRL:

-

sirolimus.

References

Penn I: Occurrence of cancers in immunosuppressed organ transplant recipients. Clin Transpl. 1994, 1994: 99-109.

Penn I: Post-transplant malignancy. Drug Saf. 2000, 23: 101-113. 10.2165/00002018-200023020-00002.

Navarro MD, Lopez-Andreu M, Rodriguez-Benot A, Aguera ML, Del Castillo D, Aljama P: Cancer incidence and survival in kidney transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2008, 40: 2936-2940. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.09.025.

Morath C, Mueller M, Goldschmidt H, Schwenger V, Opelz G, Zeier M: Malignancy in renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004, 15: 1582-1588. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000126194.77004.9B.

Melchior S, Franzaring L, Shardan A, Schwenke C, Plümpe A, Schnell R, Dreikorn K: Urological de novo malignancy after kidney transplantation: a case for the urologist. J Urol. 2011, 185: 428-432. 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.091.

Qu X, Wang X, Huang X, Li X, Li J, Zhang X: Clinical analysis of urothelial cancer after renal transplantation. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2011, 43: 579-581.

Wang J, Wang FW, Kessinger A: The natural history and outcomes of the patients with carcinosarcoma involving kidney and renal pelvis. Adv Urol. 2011, 2011: 693964-

Dimitriou RJ, Gattuso P, Coogan CL: Carcinosarcoma of the renal pelvis. Urology. 2000, 56: 508-

Yilmaz E, Birlik B, Arican Z, Guney S: Carcinosarcoma of the renal pelvis and urinary bladder: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2003, 4: 255-259. 10.3348/kjr.2003.4.4.255.

Deshmukh SD, Gaopande VL, Pande DP, Pathak GS, Kulkarni BK: Carcinosarcoma of renal pelvis with immunohistochemical correlation. Gulf J Oncol. 2012, 12: 65-69.

Chiu KC, Lin MC, Liang YC, Chen CY: Renal carcinosarcoma: case report and review of literature. Ren Fail. 2008, 30: 1034-1039. 10.1080/08860220802403192.

Hisataki T, Takahashi A, Taguchi K, Shimizu T, Suzuki K, Takatsuka K, Iwaki H: Sarcomatoid transitional cell carcinoma originating from a duplicated renal pelvis. Int J Urol. 2001, 8: 704-706. 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00396.x.

Hojo M, Morimoto T, Maluccio M, Asano T, Morimoto K, Lagman M, Shimbo T, Suthanthiran M: Cyclosporine induces cancer progression by a cell-autonomous mechanism. Nature. 1999, 397: 530-534. 10.1038/17401.

Lebranchu Y, Snanoudj R, Toupance O, Weestel PF, De Ligny BH, Buchler M, Rerolle JP, Thierry A, Moulin B, Subra JF: Five‒year results of a randomized trial comparing de novo sirolimus and cyclosporine in renal transplantation: the spiesser study. Am J Transplant. 2012, 12: 1801-1810. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04036.x.

Garrouste C, Kamar N, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Guitard J, Esposito L, Lavayssiere L, Nogier M-B, Cointault O, Ribes D, Rostaing L: Long-term results of conversion from calcineurin inhibitors to sirolimus in 150 maintenance kidney transplant patients. Exp Clin Transplant. 2012, 10: 110-118. 10.6002/ect.2011.0116.

Guba M, Yezhelyev M, Eichhorn ME, Schmid G, Ischenko I, Papyan A, Graeb C, Seeliger H, Geissler EK, Jauch K-W: Rapamycin induces tumor-specific thrombosis via tissue factor in the presence of VEGF. Blood. 2005, 105: 4463-4469. 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3540.

Lopez-Beltran A, Escudero AL, Cavazzana AO, Spagnoli LG, Vicioso-Recio L: Sarcomatoid transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. A report of five cases with clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical and DNA ploidy analysis. Pathol Res Pract. 1996, 192: 1218-1224. 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80154-3.

Acikalin MF, Kabukcuoglu S, Can C: Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the renal pelvis with giant cell tumor‒like features: case report with immunohistochemical findings. Int J Urol. 2005, 12: 199-203. 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01002.x.

Petsch M, Planz B, Tschahargane C, Caspers H: Primary sarcomatoid carcinoma of the ureter. Aktuelle Urol. 2004, 35: 137-139. 10.1055/s-2004-818363.

Thiel DD, Igel TC, Wu KJ: Sarcomatoid carcinoma of transitional cell origin confined to renal pelvis. Urology. 2006, 67: 622-e629-622. e611

Kälble T, Lucan M, Nicita G, Sells R, Revilla F, Wiesel M: EAU guidelines on renal transplantation. Eur Urol. 2005, 47: 156-166. 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.02.009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JW and XW participated in the design of this study, and they both performed the statistical analysis. CL and ZG carried out the study and, together with SY, collected important background information and drafted the manuscript. LC conceived of this study, participated in the design and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jitao Wu, Xuyun Wang contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., Wang, X., Lin, C. et al. Carcinosarcoma of native renal pelvis in recipient after a renal transplant: a case report. World J Surg Onc 12, 407 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-407

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-407