Abstract

Background

There are few comprehensive reviews of breast cancer outcomes in older women. We synthesize data to describe key findings and gaps in knowledge about the outcomes of breast cancer in this population.

Methods

We reviewed research published between 1995 and June 2003 on breast cancer quality of life and outcomes among women aged 65 and older treated for breast cancer. Outcomes included communication, satisfaction, and multiple quality of life domains.

Results

Few randomized trials or cohort studies that measured quality of life after treatment focused exclusively on older women. Studies from older women generally noted that, with the exception of axillary dissection, type of surgical treatment generally had no effect on long-term outcomes. In contrast, the processes of care, such as choosing therapy, good patient-physician communication, receiving treatment concordant with preferences about body image, and low perceptions of bias, were associated with better quality of life and satisfaction.

Conclusions

With the exception of axillary dissection, the processes of care, and not the therapy itself, seem to be the most important determinants of long-term quality of life in older women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is an important disease and one where health care services have the potential to improve the quality and quantity of life. Breast cancer is also largely a disease of old age [1, 2]. By the year 2030, one in five women in the United States will be 65 years of age or older (hereinafter referred to as "older") [3]. This demographic imperative, coupled with the dramatic increases in rates of breast cancer with advancing age, is expected to translate into a large absolute increase in the number of older women treated for and surviving breast cancer [4]. These older breast cancer survivors are likely to be a physiologically, socially, and racially heterogeneous group with varying numbers of comorbid conditions and varying outcomes following treatment for their disease [4, 5].

Older women diagnosed with breast cancer today have many different treatment options from which to choose. While most women will chose treatments that maximize survival, information about quality of life can be an important component in decision-making in several clinical situations. For instance, if a woman is considering two treatments with equivalent survival, such as mastectomy and breast conservation, then quality of life outcomes may be important considerations in her treatment decision-making. Likewise, in clinical trials of equivalent approaches, quality of life may be the identifying factor in determining the most "effective" treatment. Quality of life may also be important to women, providers, and researchers comparing the overall benefits of very toxic, but very effective regimens with those of less toxic approaches that yield somewhat lower survival. The balance of effectiveness, harms, and quality of life is especially important for older women, since treatment decisions must also factor in interactions of comorbid conditions and treatment.

Unfortunately, until recently, older women were not included in sizable numbers in breast cancer research. In addition, the inclusion of quality of outcomes into clinical and observation trials is also a fairly recent trend [6]. Thus, there is only limited information available on quality of life outcomes after different treatment regimens among diverse older populations. In this paper we review what is known about quality of life outcomes in older women with breast cancer. We highlight findings across multiple domains, discuss special considerations in measuring outcomes in this age group, and make some recommendations for future research. This review is intended to serve as a focal point for discussion and extension of existing efforts to improve the quality of breast cancer care for the growing older population.

Methods

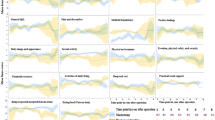

For the purposes of this review, quality of life outcomes associated with breast cancer care are defined as the net effects of the health care structure and process on the health and well-being of women diagnosed with this disease [7]. As such, quality of life is a multidimensional construct encompassing clinical, financial, functional, and psychosocial domains affected by treatment and its interactions with baseline comorbidity and circumstances (Figure 1) [6–9]. We use the term quality of life to be synonymous with the expression 'health-related quality of life' [10].

To identify relevant articles for this review, we conducted a search of published literature indexed on MedLine, CancerLit, CINAHL, and PsychInfo between 1995 and June 2003. We chose 1995 as the earliest year for review to ensure that results would be consistent with current standards of care. To capture literature encompassing a broad set of domains that might be affected by breast cancer or its treatments, we included the following terms in our searches: "breast neoplasms" and "aged" or "elderly" with "quality of life," "pain," "fatigue," "mental health," "adjustment," "body image," "satisfaction," "sexuality," "social support," "function," "communication," "cognition," or "economics." We also examined the bibliographies of retrieved articles for additional relevant citations. For citations of articles published prior to 1995, we only included sentinel articles pertinent to older women. We confined our review to original reports of randomized trials and cohort studies to examine data by age group and domain of quality of life. We excluded methodological articles, reviews, case series, and case reports, and non-English language articles. Articles were reviewed for inclusion of older women and data were abstracted on post-treatment quality of life or other outcomes for this age group. It should be noted that most observational studies to date have only examined short-term side effects and symptoms of treatment and future research is need on long-term side effects of treatments in older breast cancer survivors. We confine citations of data to results that were statistically significant, highlighting findings that are controlled for key confounding variables, such as baseline functioning [11]. We present a qualitative summary of these results. We did not attempt to conduct a meta-analysis of results since each study was conducted using varying time horizons, used different measurement tools and definitions of quality of life domains, included heterogeneous populations with a variety of tumor stages, and was conducted in different countries and cultural perspectives.

Results

Overall, few randomized trials or cohort studies measured quality of life after treatment and focused exclusively on older women [12–14]. With rare exceptions, [15–17] studies involving breast cancer outcomes were conducted in non-minority populations.

Processes of Care and Satisfaction

Satisfaction with breast cancer treatment is primarily a function of the process of care, and not the actual treatment received. A summary of these processes of care issues is found in Table 1. As one example, women who felt their surgeons initiated a conversation about treatment concerns reported higher satisfaction six months post-treatment than women who felt their surgeons communicated less, controlling for treatment and other factors [18]. Of note, surgeons who received additional training in surgical oncology have been noted by their older patients to bring up a discussion about patient concerns 60% more often (95% CI 1.02–2.56) than surgeons without specialty training [18].

Older patients may prefer and rely on physician-initiated quality of life discussions [19] and may prefer that their physicians provide information in person as opposed to written materials [20]. Higher levels of communication, both physician and patient-initiated, also affect women's perceptions of having a choice of treatment. For instance, in one study, older women who reported that their physicians asked them caring questions, asked about their concerns, or who discussed a number of options were more than twice as likely to report that they felt they were given a choice of treatment, controlling for other factors [18].

Interestingly, there appears to be a positive health benefit to having had a choice per se. In one cohort, by six months after surgery, women who reported having had a choice of therapy also reported higher adjusted global health on a linear rating scale than women who felt they had no choice (78.7 vs. 75.3 on a zero to 100 scale, p = .03) [21]. Women reporting a choice also felt more satisfied with their treatments than women who reported having no choice, considering other factors. Other investigators have also noted that women who share in the decision-making process are more likely to report being satisfied, have better post-treatment adjustment to cancer, than women who feel that they did not participate [9, 22–25]. Of note, in one longitudinal cohort, older women who received treatment that was consistent with their preferences around body image reported better mental health at follow-up than those who received surgery that was inconsistent with their preferences (e.g., receiving mastectomy without reconstruction despite a concern about maintaining body image) [26]. Interventions to facilitate decision-making that is consistent with preferences, such as CD-ROM programs, appear to have the potential to improve satisfaction with treatment decisions and with interactions with health care providers, as well as increase overall self-reported health and physical functioning [27].

Other features of women's interactions with the medical care system appear to be significant predictors of satisfaction, including perceptions of ageism (p = .01) and racism p = .03) [16]. For example, women who perceive high levels of ageism have reported less general satisfaction with their breast cancer care than women who felt there was less ageism in their interactions in the health care system.

The setting of care may also influence outcomes. For instance, for older women with multiple comorbid illnesses (>3), in-patient rehabilitation has been noted to improve multiple domains of quality of life, and many of these effects appeared to be maintained after discharge [28]. Similarly, intensive nurse case management programs have been found to improve mood and reduce feelings of uncertainty [29].

Experiences outside of the health care system, such as having less social support, have also been associated with being less satisfied with one's breast cancer care [13]. In addition, Silliman and colleagues found that older women with inadequate social support had poor psychosocial outcomes after breast cancer treatment [30].

Preferences for Treatment

In the studies conducted to date, older patients are able to state their preferences, and generally want to be fully informed about their treatment options [31–34]. Preferences are important considerations in treatment choices [35]. For example, in two studies, older breast cancer patients were willing to select a risky treatment option (chemotherapy with major toxicity) for a small increase in life expectancy (e.g., 6 months) [31, 36]. In another study, 80% of older women indicated that chemotherapy would be worthwhile if they could live an additional two years,[37] but others have found that women in this age group would accept aggressive chemotherapy for as little as a 1% increase in survival [38, 39]. Overall, these results suggest that older women are willing to trade-off short-term physical well-being, such as occurs with chemotherapy, for increased survival.

Physical Function and Pain

While many have hypothesized that breast conservation will result in better post-treatment functioning than mastectomy, in reviewing the literature we found that adjusted physical function scores were not significantly different by treatment group, [12] but rather, largely related to women's general pre-morbid level of illness [16, 17, 40–43].

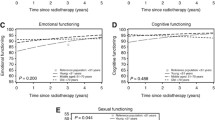

The physical function outcome of treatment relates to use of axillary node dissection [44]. In one series, the cumulative risk of having arm problems two years post-treatment were three times higher (95% CI 1.94–4.67) among women who underwent axillary surgery compared to women without axillary surgery, controlling for covariates. Arm problems after axillary dissection were reported by up to 60% of women and had a consistent negative impact on long-term functional abilities [16]. Of note, one study reported that the effects of having axillary dissection and arthritis were multiplicative two years post-surgery (Figure 2) [45]. The expected benefit of having fewer concerns about recurrence after axillary dissection has not been demonstrated [16]. Using a decision analytic approach, Parmigiani and colleagues also noted that axillary dissection had an overall negative impact on the quality-adjusted survival of 60-year-old women [46]. Other researchers have noted that long-term decrements in physical function can affect activities of daily living that are critical to an older woman's ability to live independently [42, 43]. Thus, in a Medicare population, the risks of axillary surgery may outweigh any benefits in guiding adjuvant therapy or of more detailed knowledge of prognosis [47–56]. Sentinel node biopsy has been shown to have lower mordibity than axillary dissection, [57] and may be particularly useful in older patients, especially those with arthritis or other pre-existing mobility limitations [58]. Final conclusions about the value of axillary dissection will rest on the accuracy of sentinel biopsy and women's preferences.

Radiation has not been found to increase pain or affect quality of life (measured on the EORTC breast module) in older women participating in clinical trials [14]. For older women undergoing chemotherapy, quality-adjusted benefits are similar to those seen in younger women when considering women with estrogen receptor negative tumors. For older women with estrogen positive disease, quality adjusted survival is significantly improved with chemotherapy, albeit at a somewhat lower level than seen in younger women [59].

The process of care also seems to affect physical outcomes. For instance, Mandelblatt and colleagues found that older women who perceived high levels of ageism (vs. lower levels) in the health care system or felt that they had no choice of treatment (vs. having a choice) reported significantly more bodily pain [13].

Symptoms

Symptoms, such as hot flashes on tamoxifen treatment, have been noted to decrease general quality of life in older women, either directly, or through associated disturbed sleep and fatigue [60]. Fatigue from treatment, especially in association with pain or other symptoms, can increase anxiety and depression [61]. In a cross-sectional study of 841 older patients, pain, fatigue, and insomnia were significantly related to losses in physical functioning, even after controlling for cancer treatment and comorbid conditions [62]. In a one-year follow-up of the same cohort, chemotherapy was related to reports of fatigue in the short-term, but not at one-year post-treatment [63]. A recent randomized controlled trial of exercise training[64] suggests that overall quality of life, as measured by the FACT-B scale, increases significantly in the postmenopausal breast cancer survivors who exercise regularly. Reductions in fatigue and improvements in mood were also reported, indicating that further testing of exercise interventions in older breast cancer survivors is warranted.

Mental Health and Overall Impact

The processes of care, including feeling like one had a choice of treatment also are important predictors of health outcomes. For example, in one cohort of older women, choice was independently associated with reports of better mental health [13]. Recently, Keating and colleagues extended these results and demonstrated that the concordance between desired and actual decision-making was actually more important than the actual process itself [65].

Receipt of chemotherapy (yes vs. no) has not been related to any long-term mental health outcomes except for having a perception that breast cancer had a greater impact on one's life, even after considering stage and other factors [13]. One aspect of this negative impact has been distress about weight gain associated with chemotherapy [66].

Interestingly, better educated women report that breast cancer has a greater impact on their lives than their less well educated counterparts, but the oldest women (75+ years) rate breast cancer as having less of an impact on their lives than younger women (67 to 74 years) [13]. The experience of having breast cancer has also been noted to have positive effects on women's lives, [67]and feeling a sense of purpose in life has been found to have a greater impact on quality of life than breast cancer itself [67].

Interestingly, older women are less likely to use mental health (or alternative medicine) services than younger patients [68]. However, participation in mental health support, such as performing expressive journaling has been found to improve short-term (i.e., 3 months) mental health outcomes and vitality and to decrease the number of medical appointments for cancer-related symptoms [69].

Cognition

Patients with breast cancer frequently complain of problems with their memory and concentration. Such reports are known colloquially as "chemobrain" or "chemofog" http://www.pinkribbon.com/chemobr.htm. Empirical evidence is accumulating that cognitive problems are associated with use of surgery and chemotherapy (e.g., Ahles et al, 2002) [70]. For example, Cimprich [71] examined attention and reported decrements in attention-related tasks in older, but not in younger breast cancer patients. Tamoxifen has also been found to negatively affect cognition [72] in a sample of women aged 57–75.

As cognitive problems interact with fatigue, pain, depression, and sleep quality in their impact on functioning, interventions to improve cognition (and/or reduce these other symptoms) could lead to improvements in other domains. Cognitive behavior therapy has been found to be effective in improving sleep, cognition, and quality of life in younger groups [73] and such interventions could be expanded to include older women. Examination of long-term cognitive effects of adjuvant treatment using validated neuropsychological batteries and evaluation of fatigue prior to and after surgery and adjuvant therapy is warranted. Improving cognition may also have long-term effects on survival, since impaired cognitive status has been associated with poorer survival, controlling for age, stage, and treatment [41].

Body Image and Sexuality

In the multi-center EORTC trial of mastectomy versus breast conservation (plus tamoxifen) there was a trend towards better body image one year after treatment among women 70 years and older [12]. In other studies, older women undergoing breast conservation have reported better body image (and mental health) two-years post-treatment compared to the women who had undergone mastectomy, [26, 74] although results have been inconsistent [75, 76]. National estimates of breast reconstruction rates following mastectomy demonstrate lower use among older women, with only 1.3% to 4.1% of women over age 70 having reconstruction compared to 17.9% of younger women [77, 78].

There is a paucity of data on sexual feelings and outcomes in older women with breast cancer. In our own research, we observed that 15.1% of women had been sexually active prior to breast cancer diagnosis and that many women reported that breast cancer had either a "very negative" or "somewhat negative" impact on their sexual feelings and interest (Mandelblatt, unpublished data, 2003).

Social and Role Function

Social and role functions are inextricably linked to social support and integration prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Breast cancer survivors who are more socially integrated before their breast cancers report better post-treatment role function and vitality than less socially integrated women [79]. In fact, Michael and colleagues report that social integration accounts for greater variance in quality of life than treatment itself [79]. As a result, others have developed social support interventions targeted to breast cancer survivors with poor support systems. In a recent randomized, prospective trial, the quality of life of older women improved when communicating with a community-based nurse case manager who provided help with managing comorbid conditions, assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), and help navigating the health care system [80]. Similarly, Silliman and colleagues [30] found that older women relied heavily on their physicians for support and they suggest enhanced physician-patient communication may improve emotional health outcomes in these women. With intense support, women generally report better well-being and lower distress, [81] although some studies have not been able to demonstrate this effect [82].

Economic Outcomes

Breast cancer accounted for between one-fifth and one-quarter of the $157 billion dollars in cancer costs in the United States in 2001 [83]. Lower costs per woman have been reported for older women compared to costs for younger women[84]and is probably partly explained by less aggressive treatment offered to older women [35]. Interestingly, economic market forces affect costs and patterns of care in older women. For example, Hadley and colleagues examined Medicare claims and demonstrated that women living in areas with the highest ratio of mastectomy fees relative to breast conservation fees were significantly more likely to have mastectomy, while women in areas where there was less of a fee differential between the two procedures were most likely to get breast conservation [85].

In one economic analysis spanning a five year horizon after breast cancer treatment, Polsky and colleagues found that the initial costs of six weeks of radiation makes breast conservation more expensive than mastectomy, with no significant differences in quality-adjusted survival. Summing costs and outcomes over five years post-treatment, breast conservation and radiation cost more than $200,000 per quality adjusted life year saved (QALY) compared to mastectomy. In an alternative formulation, where breast conservation and radiation are compared to open choice, and choice is assumed to have a utility in and of itself (as noted above), the cost-effectiveness ratio for breast conservation drops to as low as approximately $50,000 to $75,000 per QALY, well within the threshold for current medical expenditures [86].

Caregiver Burden

There is a paucity of data about the impact of breast cancer in older women on their family members and caregivers. Female gender, older age, and past grief experiences have been associated with increased distress and grief in spousal caregivers of cancer patients [87]. In one study, daughters and sisters of women with breast cancer perceived that their information and support needs were not well met [88]. In another report, Northouse and colleagues found that family members of patients with recurrent disease experienced decrements in emotional well being, and that negative impact was mediated by family hardiness and social support [89]. Among caregivers of a small sample of cancer patients sleep problems predicted 63.6% of the variance in caregiver depression [90]. Since older women are likely to be primary caregivers for their spouses or grandchildren, when they are undergoing breast cancer treatment or terminally ill, caregiver burden is compounded by loss of this key family resource. Overall, more research is needed to assess caregiver needs and develop appropriate interventions geared to older patients and their families.

Special Considerations in Quality of Life Measurement

To date, quality of life assessments in older women have employed a wide variety of methods and tools to assess outcome. Some limitations of prior evaluations include use of a limited number of domains, lack of standard agreement on the appropriate comparison groups (e.g., other cancer patients, women without cancer) or failure to compare results to any control group, and inclusion of narrow segments of the breast cancer population (e.g., only well-educated, non-minority women). Furthermore, few prior studies were designed to specifically evaluate outcomes for older women, particularly to assess the interactions of decrements in function or well being associated with treatment with comorbid conditions. For example, mild treatment related peripheral neuropathy might significantly impair ambulation in an older diabetic woman with pre-existing neuropathic changes. Visual problems associated with tamoxifen could be especially detrimental to older women with underlying visual impairment. Lack of control for baseline function may also over-estimate the magnitude of treatment-related decrements in quality of life.

Certain domains of quality of life may be more salient to older women than other groups of breast cancer patients. For instance, for older women, ambulation and mobility impairments may make the difference between independent living and assisted living [43, 91]. Likewise, mild fatigue may have a multiplicative effect in impairing activities of daily living in a frail older woman, while only being bothersome to a younger woman. Presence of comorbid conditions may also limit discussion of treatment options [92] or complicate delivery of treatment such as chemotherapy [40, 93, 94]. Conversely, it is important to recognize heterogeneity in elderly women such that special subsets will have few chronic diseases and greater functional status; such patients will be able to tolerate more intensive therapy (i.e. "fit elderly") [95].

Administration of quality of life evaluations for older patients may also be difficult and can compromise the quality of data obtained. For instance, visual or hearing problems may lead to miscomprehension of survey items, and memory impairments may lead to obtaining inaccurate data, especially about more distal events. Older women also may telescope time and discount the importance of health events that are in the future versus those in the present.

Thus, as indicated by the pathways depicted in Figure 1, consideration of comorbidity data is essential for future outcomes research among older women. Exclusion of older women with multiple comorbidities from clinical trials may result in less representative samples of breast cancer patients and interfere with improving understanding of the impact that such conditions have on quality of life. Specialized tools and methodologies may need to be developed and applied to research with older female populations to fully capture non-cancer influences on outcomes. Examples could include the multiple informants approach when working with cognitively impaired women [96] or the Comprehensive Prognostic Index [97] which is created by combining indices of comorbidities that impact breast cancer survival with age and cancer stage.

Thus, there are many methodological challenges inherent in working with older populations. Researchers interested in studying older women's quality of life will need to be cognizant of these special issues to ensure high quality results. Further research is necessary to ensure that we are using the proper approaches to obtain valid information and to improve the quality of care for older women.

Future Directions

This review is intended to highlight key outcomes among older women surviving breast cancer. Our results can be used to inform clinical decision-making and design interventions to improve quality of care and optimize functioning in this growing population (Table 2). Additional research is needed to understand dynamic interactions between cancer survivorship, comorbidities, aging per se, poverty, ethnicity, and the processes of interaction with the medical care system in producing the observed outcomes of care.

References

National Cancer Institute: SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1973–1995. Specific data from NCHS Public Use Tape. (Edited by: Ries LAG, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA and Edwards BK). Bethesda, MD 1998.

National Cancer Institute DCCPS,Surveillance Research Program,Cancer Statistics Branch,released April: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Public-Use Data (1973–1998). 2001.

BJ Soldo, EM Agree: America's elderly. Washington, DC, Population Reference Bureau, Inc. 1988.

TL Lash, RA Silliman: Prevalence of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998, 90: 399–400. 10.1093/jnci/90.5.399

JS Mandelblatt, AS Bierman, K Gold, Y Zhang, al et: Constructs of burden of illness in elderly breast cancer patients: A comparison of measurement methods. Health Serv Res 1999, 36: 1085–1107.

JS Mandelblatt, JM Eisenberg: Historical and methodological perspectives on cancer outcomes research. Oncology (Huntingt) 1995, 9: 23–32.

DL Patrick, P Erickson: Health status and health policy. Quality of Life in Health Care Evaluation and Resource 1993.

MF Drummond, GL Stoddard, GW. Torrance: Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care programmes. New York, NY, Oxford University Press 1987.

LJ Fallowfield, A Hall, GP Maguire, M Baum: Psychological outcomes of different treatment policies in women with early breast cancer outside a clinical trial. Br Med J 1990, 301: 575–580.

PA. Ganz: Quality of life measures in cancer chemotherapy, methodology and implications. PharmacoEcon 1994, 5: 376–388.

Bottomley A, Therasse P: Quality of life in patients undergoing systemic therapy for advanced breast cancer. Lancet Oncol 2002, 3: 620–628. 10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00876-8

de Haes JC, Curran D, Aaronson NK, Fentiman IS: Quality of life in breast cancer patients aged over 70 years, participating in the EORTC 10850 randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 2003, 39: 945–951. 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00149-7

J Mandelblatt, S.B Edge, NJ Meropol, R. Senie, T Tsangaris, L Grey, al. et: Predictors of long-term outcomes in older breast cancer survivors: perceptions versus patterns of care. J Clin Oncol 2003, 21: 855–863. 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.007

Rayan G, Dawson LA, Bezjak A, Lau A, Fyles AW, Yi QL, Merante P, Vallis KA: Prospective comparison of breast pain in patients participating in a randomized trial of breast-conserving surgery and tamoxifen with or without radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003, 55: 154–161. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)03826-9

Gotay CC, Holup JL, Pagano I: Ethnic differences in quality of life among early breast and prostate cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2002, 11: 103–113. 10.1002/pon.568

J Mandelblatt: Variations In Breast Cancer Treatment in Older Medicare Beneficiaries: Is it black or white? Cancer 2002.

K Ashing-Giwa, PA Ganz, L Petersen: Quality of life of African-American and white long term breast carcinoma survivors. Cancer 1999, 85: 418–426. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990115)85:2<418::AID-CNCR20>3.0.CO;2-9

Liang W, C Burnett, JH Rowland, NJ Meropol, L Eggert, YT Hwang, al. et: Communication between physicians and older women with localized breast cancer: implications for treatment and patient satisfaction. J Clin Oncol 2002, 20: 1008–1016. 10.1200/JCO.20.4.1008

Detmar SB, Aaronson NK, Wever LD, Muller M, Schornagel JH: How are you feeling? Who wants to know? Patients' and oncologists' preferences for discussing health-related quality-of-life issues. J Clin Oncol 2000, 18: 3295–3301.

Maly RC, Leake B, Silliman RA: Health care disparities in older patients with breast carcinoma: informational support from physicians. Cancer 2003, 97: 1517–1527. 10.1002/cncr.11211

D Polsky, N Keating, J Weeks, K Schulman: Patient Choice of Breast Cancer Treatment: Impact on health state preferences. Med Care 2002.

J Morris, R Ingham: Choice of surgery for early breast cancer: Psychosocial considerations. Soc Science & Med 1988, 27: 1257–1262. 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90355-3

BR Cassileth, RV Zupkis, K Sutton-Smith, al et: Information and participation preferences among cancer patients. Ann Intern Med 1980, 92: 832–836.

J Morris, GT Royle, I Taylor: Changes in the surgical management of early breast cancer in England. J Royal Soc Med 1989, 82: 12–14.

A Liberati, G Apolone, A Nicolucci, C Confalonieri, R Fossati, R Grilli, al et: The role of attitudes, beliefs, and personal characteristics of Italian physicians in the surgical treatment of early breast cancer. Am J Pub Health 1991, 81: 38–42.

Figueiredo MI, Cullen J, Hwang YT, Mandelblatt JS: Body image and emotional well-being in older women with breast cancer. (Edited by: 24th Annual Society of Behavioral Medicine Meeting). Salt Lake City, UT 2003.

Molenaar S, Sprangers MA, Rutgers EJ, Luiten EJ, Mulder J, Bossuyt PM, van Everdingen JJ, Oosterveld P, de Haes HC: Decision support for patients with early-stage breast cancer: effects of an interactive breast cancer CDROM on treatment decision, satisfaction, and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2001, 19: 1676–1687.

ME Heim, S Kunert, I. Ozkan: Effects of impatient rehabilitation on health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients. Onkologie 2001, 24: 268–272. 10.1159/000055090

Ritz LJ, Nissen MJ, Swenson KK, Farrell JB, Sperduto PW, Sladek ML, Lally RM, Schroeder LM: Effects of advanced nursing care on quality of life and cost outcomes of women diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2000, 27: 923–932.

RA Silliman, KA Dukes, LM Sullivan, SH Kaplan: Breast cancer care in older women: Sources of information, social support, and emotional health outcomes. Cancer 1998, 83: 706–711. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980815)83:4<706::AID-CNCR11>3.3.CO;2-R

RP McQuellon, HB Muss, SL Hoffman, G Russell, al et: Patient preferences for treatment of metastatic breast cancer: A study of women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1995, 13: 858–868.

Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Sutherland HJ, Tritchler DL, Lockwood GA, Till JE, Ciampi A, Scott JF, Lickley LA, Fish EB: Benign and malignant breast disease: the relationship between women's health status and health values. Med Decis Making 1991, 11: 180–188.

BJ McNeil, SG Pauker, Jr. Sox HC, A Tversky: On the elicitation of preferences for alternative therapies. N Engl J Med 1982, 306: 1259–1262.

Till JE, Sutherland HJ, Meslin EM: Is there a role for preference assessments in research on quality of life in oncology? Qual Life Res 1992, 1: 31–40.

JS Mandelblatt, J Hadley, J Kerner, K Schulman, al et: Patterns of breast cancer treatment in the elderly: Patient, physician, and medical system influences. 1999.

SB Yellen, DF Cella: Someone to live for: Social well-being, parenthood status, and decision-making in oncology. J Clin Oncol 1995, 13: 1255–1264.

RJ Simes, K Cocker, P Glaszious, al et: Costs and benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: An assessment of patient preferences. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1989, 8: 52.

ML Slevin, L Stubbs, HJ Plant, al et: Attitudes to chemotherapy: Comparing views of patients with cancer with those of doctors, nurses and general public. BMJ 1990, 300: 1458–1460.

PM Ravdin, IA Siminoff, JA Harvey: Survey of breast cancer patients concerning their knowledge and expectations of adjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol 1998, 16: 515–521.

Newschaffer CJ, Penberthy L, Desch CE, Retchin SM, Whittemore M: The effect of age and comorbidity in the treatment of elderly women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. Arch Intern Med 1996, 156: 85–90. 10.1001/archinte.156.1.85

JS Goodwin, JM Samet, WC Hunt: Determinants of survival in older cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996, 88: 1031–1038.

WA Satariano, DR Ragland, GN DeLorenze: Limitations in upper-body strength associated with breast cancer: a comparison of black and white women. J Clin Epidemiol 1996, 49: 535–44. 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00565-X

RA Silliman, MN Prout, T Field, et al: Risk factors for a decline in upper body function following the treatment for early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1999, 54: 25–30. 10.1023/A:1006159720583

Beaulac SM, McNair LA, Scott TE, LaMorte WW, Kavanah MT: Lymphedema and quality of life in survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Arch Surg 2002, 137: 1253–1257. 10.1001/archsurg.137.11.1253

J Mandelblatt, S Edge, N Meropol, R Senie, T Tsangaris, L Grey, al. et: Sequelae of axillary lymph node dissection in older women with stage 1 and 2 breast carcinoma. Cancer 2002, 95: 2445–2454. 10.1002/cncr.10983

G Parmigiani, DA Berry, EP Winer, C Tebaldi, JD Iglehart, LR Prosnitz: Is axillary lymph node dissection indicated for early-stage breast cancer? a decision analysis. J Clin Oncol 1999, 17: 1465–73.

E Maunsell, J Brisson, L Deschenes: Arm problems and psychological distress after surgery for breast cancer. Can J Surg 1993, 36: 315–320.

MW Kissin, GQ Della Rovere, D Easton, G Westbury: Risk of lymphoedema following treatment of breast cancer. Br J Surg 1986, 73: 580–584.

Vevers JM Roumen RM, Vingerhoets AJ Vrengdenhil G,Coebergh JW,Crommelin MA,et al: Risk, severity and predictors of physical and psychological morbidity after axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2001, 37: 991–999. 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00067-3

V Velanovich: Axillary Lymph Node Dissection for Breast Cancer: A decision analysis of T1 lesions. Annals of Surgical Oncology 1997, 5: 131–139.

B Cady: Is axillary lymph node dissection necessary in routine management of breast cancer? No. Important Advances in Oncology 1996, 251–265.

P Goss, T Hack, L Cohen, P Ritvo, J Katz: Long term physical and psychological morbidity of axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in patients with breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996, 15: 123.

MA Warmuth, G Bowen, LR Prosnitz, L Chu, G Broadwater, B Peterson, G Leight, EP Winer: Complications of axillary lymph node dissection for carcinoma of the breast: A report based on a patient survey. Cancer 1998, 83: 1362–1368. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981001)83:7<1362::AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-2

D Ivens, AL Hoe, TJ Podd, CR Hamilton, I Taylor, GT Royle: Assessment of morbidity from complete axillary dissection. Br J Cancer 1992, 66: 136–138.

TF Hack, L Cohen, J Katz, LS Robson, P Goss: Physical and psychological morbidity after axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999, 17: 142–149.

Kuehn T, Klauss W, Darsow M, Regele S, Flock F, Maiterth C, Dahlbender R, Wendt I, Kreienberg R: Long-term morbidity following axillary dissection in breast cancer patients--clinical assessment, significance for life quality and the impact of demographic, oncologic and therapeutic factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000, 64: 275–286. 10.1023/A:1026564723698

Swenson KK, Nissen MJ, Ceronsky C, Swenson L, Lee MW, Tuttle TM: Comparison of side effects between sentinel lymph node and axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2002, 9: 745–753. 10.1245/ASO.2002.02.007

Schijven MP, Vingerhoets AJ, Rutten HJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Roumen RM, van Bussel ME, Voogd AC: Comparison of morbidity between axillary lymph node dissection and sentinel node biopsy. Eur J Surg Oncol 2003, 29: 341–350. 10.1053/ejso.2002.1385

Cole BF, Gelber RD, Gelber S, Coates AS, Goldhirsch A: Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised clinical trials with quality-adjusted survival analysis. Lancet 2001, 358: 277–286. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05483-6

Stein KD, Jacobsen PB, Hann DM, Greenberg H, Lyman G: Impact of hot flashes on quality of life among postmenopausal women being treated for breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000, 19: 436–445. 10.1016/S0885-3924(00)00142-1

Stone P, Richards M, A'Hern R, Hardy J: A study to investigate the prevalence, severity and correlates of fatigue among patients with cancer in comparison with a control group of volunteers without cancer. Ann Oncol 2000, 11: 561–567. 10.1023/A:1008331230608

Given B, Given C, Azzouz F, Stommel M: Physical functioning of elderly cancer patients prior to diagnosis and following initial treatment. Nurs Res 2001, 50: 222–232. 10.1097/00006199-200107000-00006

Given CW, Given B, Azzouz F, Kozachik S, Stommel M: Predictors of pain and fatigue in the year following diagnosis among elderly cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001, 21: 456–466. 10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00284-6

KS Courney, JR Mackey, GJ Bell, LW Jones, CJ Field, AS Fairey: Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: Cardipulmonary and quality of life outcomes. JCO 2003, 21: 1660–1668.

N Keating, E Guadagnoli, M Landrum, C Borbas, J Weeks: Patients participation in treatment decision making: Should Physicians match patients desired levels of involvement? J Clin Oncol 2002, 20: 1473–1479. 10.1200/JCO.20.6.1473

McInnes JA, Knobf MT: Weight gain and quality of life in women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001, 28: 675–684.

Tomich PL, Helgeson VS: Five years later: a cross-sectional comparison of breast cancer survivors with healthy women. Psychooncology 2002, 11: 154–169. 10.1002/pon.570

Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Hedderson MM, Schwartz SM, Standish LJ, Bowen DJ, Marshall LM: Types of alternative medicine used by patients with breast, colon, or prostate cancer: predictors, motives, and costs. J Altern Complement Med 2002, 8: 477–485. 10.1089/107555302760253676

Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Cameron CL, Bishop M, Collins CA, Kirk SB, Sworowski LA, Twillman R: Emotionally expressive coping predicts psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000, 68: 875–882. 10.1037//0022-006X.68.5.875

Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, Cole B, Mott LA, Skalla K, Whedon MB, Bivens S, Mitchell T, Greenberg ER, Silberfarb PM: Neuropsychologic impact of standard-dose systemic chemotherapy in long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2002, 20: 485–493. 10.1200/JCO.20.2.485

Cimprich B: Age and extent of surgery affect attention in women treated for breast cancer. Res Nurs Health 1998, 21: 229–238. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199806)21:3<229::AID-NUR6>3.0.CO;2-J

Paganini-Hill A, Clark LJ: Preliminary assessment of cognitive function in breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000, 64: 165–176. 10.1023/A:1006426132338

Quesnel C, Savard J, Simard S, Ivers H, Morin CM: Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in women treated for nonmetastatic breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003, 71: 189–200. 10.1037//0022-006X.71.1.189

Amichetti M, Caffo O: Quality of life in patients with early stage breast carcinoma treated with conservation surgery and radiotherapy. An Italian monoinstitutional study. Tumori 2001, 87: 78–84.

Nissen MJ, Swenson KK, Ritz LJ, Farrell JB, Sladek ML, Lally RM: Quality of life after breast carcinoma surgery: a comparison of three surgical procedures. Cancer 2001, 91: 1238–1246. 10.1002/1097-0142(20010401)91:7<1238::AID-CNCR1124>3.3.CO;2-O

Cohen L, Hack TF, de Moor C, Katz J, Goss PE: The effects of type of surgery and time on psychological adjustment in women after breast cancer treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 2000, 7: 427–434.

Morrow M, Scott SK, Menck HR, Mustoe TA, Winchester DP: Factors influencing the use of breast reconstruction postmastectomy: a National Cancer Database study. J Am Coll Surg 2001, 192: 1–8. 10.1016/S1072-7515(00)00747-X

Alderman AK, McMahon L.,Jr., Wilkins EG: The national utilization of immediate and early delayed breast reconstruction and the effect of sociodemographic factors. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003, 111: 695–703. 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041438.50018.02

Michael YL, Berkman LF, Colditz GA, Holmes MD, Kawachi I: Social networks and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a prospective study. J Psychosom Res 2002, 52: 285–293. 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00270-7

A Jennings-Sanders, ET. Anderson: Older women with breast cancer perceptions of the effectiveness of nurse case managers. Nursing Outlook 2003, 51: 108–114. 10.1016/S0029-6554(03)00083-6

Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, Zuckerman E, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, Cooper MR, Harris L, Tkaczuk KH, Perry MC, Budman D, Norton LC, Holland J: Social support as a buffer to the psychological impact of stressful life events in women with breast cancer. Cancer 2001, 91: 443–454. 10.1002/1097-0142(20010115)91:2<443::AID-CNCR1020>3.0.CO;2-Z

Sandgren AK, McCaul KD, King B, O'Donnell S, Foreman G: Telephone therapy for patients with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2000, 27: 683–688.

Radice D, Redaelli A: Breast cancer management: quality-of-life and cost considerations. Pharmacoeconomics 2003, 21: 383–396.

WE Barlow, SH Taplin, CK Yoshida, DS Buist, D Seger, M Brown: Cost comparison of mastectomy versus breast-conserving therapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001, 93: 447–455. 10.1093/jnci/93.6.447

J Hadley, J Mandelblatt, JM Mitchell, JC Weeks, E Guadagnoli, YT Hwang, al. et: Medicare breast surgery fees and treatment received by older women with localized breast cancer. Health Serv Res 2003, 38: 553–573.

Polsky D, Glick HA, Willke R, Schulman K: Confidence intervals for cost-effectiveness ratios: a comparison of four methods. Health Econ 1997, 6: 243–252. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1050(199705)6:3<243::AID-HEC269>3.0.CO;2-Z

O Gilbar, H. Ben-Zur: Bereavement of spouse caregivers of cancer patients. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 2002, 72: 422–432. 10.1037//0002-9432.72.3.422

K Chalmers, S Marles, D Tataryn, S Scott-Findlay, K. Serfas: Reports of information and support needs of daughters and sisters of women with breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care 2003, 12: 81–90.

Northouse LL, Mood D, Kershaw T, Schafenacker A, Mellon S, Walker J, Galvin E, Decker V: Quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. J Clin Oncol 2002, 20: 4050–4064. 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.054

PA Carter, BL. Chang: Sleep and depression in cancer caregivers. Cancer Nursing 2000, 23: 410–415.

WA Satariano, DR Ragland: Upper-body strength and breast cancer: a comparison of the effects of age and disease. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1996, 51: M215–9.

Velanovich V, Gabel M, Walker EM, Doyle TJ, O'Bryan RM, Szymanski W, Ferrara JJ, Lewis F.R.,Jr.: Causes for the undertreatment of elderly breast cancer patients: tailoring treatments to individual patients. J Am Coll Surg 2002, 194: 8–13. 10.1016/S1072-7515(01)01132-2

R Yancik, MN Wesley, LA Ries, RJ Havlik, BK Edwards, JW Yates: Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA 2001, 285: 885–892.

Blackman SB, Lash TL, Fink AK, Ganz PA, Silliman RA: Advanced age and adjuvant tamoxifen prescription in early-stage breast carcinoma patients. Cancer 2002, 95: 2465–2472. 10.1002/cncr.10985

Firat S, Gore E, Byhardt RW: Do "elderly fit" patients have less comorbidity? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003, 55: 1166–1168. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)04577-7

Lash TL, Thwin SS, Horton NJ, Guadagnoli E, Silliman RA: Multiple informants: a new method to assess breast cancer patients' comorbidity. Am J Epidemiol 2003, 157: 249–257. 10.1093/aje/kwf193

Fleming ST, Rastogi A, Dmitrienko A, Johnson KD: A comprehensive prognostic index to predict survival based on multiple comorbidities: a focus on breast cancer. Med Care 1999, 37: 601–614. 10.1097/00005650-199906000-00009

Buchner DM, Wagner EH: Preventing frail health. Clin Geriatr Med 1992, 8: 1–17.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Trina McClendon for manuscript preparation. This review is dedicated to the memory of Natalie Davis Springarn: your example of living and dying gracefully with breast cancer give us hope and guide our work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mandelblatt, J., Figueiredo, M. & Cullen, J. Outcomes and quality of life following breast cancer treatment in older women: When, why, how much, and what do women want?. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1, 45 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-45

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-45