Abstract

Background

It has frequently been reported that Plasmodium vivax suppressed Plasmodium falciparum and ameliorated disease severity in patients infected with these two species simultaneously. The authors investigate the hypothesis that immunological responses stimulated by P. vivax may play a role in suppressing co-infecting P. falciparum.

Methods

Sera, taken sequentially from one of the authors (YN) during experimental infection with P. vivax, were added to in vitro cultures of P. falciparum. Cross-reactive antibodies against P. falciparum antigens, and cytokines were measured in the sera.

Results

Significant growth inhibitory effects upon P. falciparum cultures (maximally 68% inhibition as compared to pre-illness average) were observed in the sera collected during an acute episode. Such inhibitory effects showed a strong positive temporal correlation with cross-reactive antibodies, especially IgM against P. falciparum schizont extract and, to a lesser degree, IgM against Merozoite Surface Protein (MSP)-119. Interleukin (IL)-12 showed the highest temporal correlation with P. vivax parasitaemia and with body temperatures in the volunteer.

Conclusion

These results suggest the involvement by cross-reactive antibodies, especially IgM, in the interplay between plasmodial species. IL-12 may be one of direct mediators of fever induction by rupturing P. vivax schizonts, at least in some subjects. Future studies, preferably of epidemiological design, to reveal the association between cross-reactive IgM and cross-plasmodial interaction, are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A number of studies have reported that Plasmodium species apparently suppressed each other, in population [1, 2], or in a mixedly-infected individual [3–8]. It is noteworthy that the emergence of Plasmodium vivax in patients' peripheral blood has led to a "total disappearance" of Plasmodium falciparum, while passive transfer of P. falciparum-immune IgG exhibited weaker suppressive effects on P. falciparum in these patients [9]. The severity of P. falciparum infection has been reported to be dramatically ameliorated in patients simultaneously infected with P. vivax [2, 10]. Mutual suppression between Plasmodium parasites has been thoroughly reviewed [11–13]. These observations have led to speculation that the much lower disease-specific mortality and case fatality rate from malaria in Asia-Pacific region than in Africa may be due to the presence of so-called "benign" P. vivax malaria [14, 15], because P. falciparum is by far the most dominant in sub-Saharan Africa [16]. Therefore, understanding the interaction of these Plasmodium species is important, especially because several P. vivax vaccines are currently being developed. The authors hypothesized that the host immunological reactions to infecting P. vivax might be playing a role in this suppression of co-infecting P. falciparum. Although such a notion has been long held [17–19], actual data has been rarely available for human malaria. However, any study design that leaves ailing human volunteers (other than the researcher) untreated is unacceptable from a bioethical point of view. By contrast, "almost all of the associated legal, ethical, and metaphysical problems vanish" with self-recruitment of the researcher, according to the founder of modern bioethics [20]. Hence, to examine the hypothesis, YN volunteered to be infected with P. vivax, and his serum was collected sequentially during this infection. The inhibitory effect of these sera upon P. falciparum growth was quantified by using an in vitro culture technique. To illustrate the kinetics of the immunological processes, immunological mediators including cross-reactive antibodies against P. falciparum and cytokines in these sera were also measured.

Case presentation

Human subjects

The volunteer (YN, an author) was a 35-year old Japanese man. He had previously experienced Plasmodium infection only once, when he was infected with P. vivax, one year before the present study [21]. Control subjects were composed of 21 healthy adult Bangkok residents (9 male and 12 female, median age: 33 years) who had never been infected with any Plasmodium species.

Plasmodium vivax parasites

In January 2001, 2 ml of whole blood was obtained from an adult patient who was infected with P. vivax near Thailand-Myanmar border. PCR confirmed that this blood was infected with P. vivax but not with other Plasmodium species [22]. Fifty female anopheline mosquitoes were fed on this blood in a membrane feeder. One month later, sporozoites were detected in the salivary glands of two randomly selected mosquitoes.

Course of illness in the volunteer

The volunteer was challenged by another infected mosquito on day 0. The mosquito was tested by PCR, confirming the presence of P. vivax only. The volunteer was continuously monitored in Mahidol University Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Bangkok, a non-malarious region. The volunteer experienced microscopically positive parasitaemias of P. vivax from day 14. From day 20, a regimen of artemisinin (200 mg/day for 3 days) and doxycycline (100 mg/day for 6 days) was administered to radically terminate the blood-stage parasites. The blood collection was resumed on day 29, when the anti-malarial drugs should have been completely eliminated from the volunteer's blood [23, 24]. Subsequently YN relapsed, and parasites were detected in the peripheral blood microscopically on day 36. After experiencing an acute phase, he was treated with chloroquine (1,500 mg on day 52; 500 mg on day 53 and 54), and with primaquine (15 mg per day for 14 days) to radically kill both the blood-stage parasites and the hypnozoites. The illness, especially headache, was subjectively much milder than in the previous infection one year before; nevertheless, the peak parasitaemia was three-times higher than the previous one.

Blood collection

Venous blood was collected every day as follows: (i) the pre-challenge period (days -6 to 0); (ii) the initial infection period (days 1 to 20); (iii) the relapse period (days 29 to 53). Blood was collected 7, 29 and 29 times during the periods (i), (ii) and (iii), respectively. The sera collected during the period (i) provided the baseline. The volunteer was phlebotomized once per day when the body temperature did not show a noticeable elevation; otherwise twice per day (one at a peak of body temperature and one at about 12 hours after the peak). Blood was allowed to coagulate at 25°C for 20 minutes, and centrifuged. Serum was preserved at -70°C until use. No drugs were administered from day -20 and throughout the entire period of the infection, except for the above medications.

In vitro cultures of Plasmodium falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum was cultured in vitro, in each of the volunteer's sera, as follows. K1 strain of P. falciparum was synchronized into the ring form stage [25], and subsequently mixed with the incomplete medium and the purified type-O red blood cells, so that the P. falciparum parasitaemia was set to 0.5% and the haematocrit was adjusted to 50%. In the each well on a 96-well flat-bottomed plate, 10 μl of this parasite preparation, 45 μl of the incomplete medium, and 35 μl of each of the volunteer's sera were mixed (final volume 90 μl; hematcrit 5.6%; serum concentration 39% (v/v)). The plate was incubated under 5% CO2pressure at 37°C. After 24 hours, 60 μl of the supernatant was replaced by 35 μl of the the same serum and 45 μl of incomplete medium. After a further 28 hours, two thin films were prepared from each well. The percent reduction from the baseline was defined as the growth inhibition of the each serum. As a result, the volunteer's sera collected during the relapse period exhibited growth inhibitory effects, significantly elevated above the baseline level (Figure 1c). This was particularly marked between days 46 and 51 (mean: 42%, maximum: 68%), and to a lesser degree, between days 33 and 35.

Course of illness in the volunteer and in vitro growth inhibition on P. falciparum exhibited by the volunteer's sera. (a) Plasmodium vivax parasitaemias (percentage of infected red blood cells) determined microscopically in the volunteer are represented by a line, while detection of P. vivax by PCR is denoted by horizontal black bars. (b) Body temperatures measured at the time of phlebotomies are shown. (c) The solid line represents the average of in vitro growth inhibition obtained from four cultures, while the dotted lines represent standard errors. The broken line denotes the upper 95% confidence limit of the baseline sera. Days of high values are denoted on the symbols in this and subsequent figures. Day 0 is the day of challenge.

Measurement of cross-reactive antibodies

To investigate the degree of cross-reactive immunity in the sera, we measured IgM and IgG levels against P. falciparum schizont extract and Merozoite Surface Protein (MSP)-119 of P. falciparum. ELISA was carried out as previously described [26]. P. falciparum schizont extract and MSP-119(Wellcome sequence) were obtained as described in [26–28]. Each IgG plate contained a standard dilution series of a laboratory reference hyper-immune adult Gambian plasma pool. For IgM, a standard dilution series of non-specific IgM purified from human serum (Sigma-Aldrich) was coated in one set of wells. Of note, IgM values against P. falciparum schizont extract and MSP-119 were elevated after day 47 (Figure 2a,b). The temporal correlation between pairs of time-series variables, such as growth inhibitory effect and antibody level, were quantified as follows. First, simple linear regression was applied. Next, since the blood was sampled at non-random time points and temporally non-independent, we also employed Prais-Winsten's method for time-series regression [29]. In doing so, the time-axis was divided into discrete time-steps of a fixed length (half day, one day and two days). When a time-step included more than one sample, the averaged value was used. As a result, the in vitro growth inhibitory effects on P. falciparum and the levels of IgM against P. falciparum (especially, schizont extract) showed strong temporal correlation, in any time-step lengths examined (Table 1).

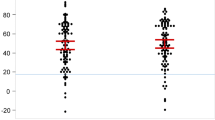

Cross-reactive antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum antigens. (a) IgM against P. falciparum schizont extract, (b) IgM against P. falciparum Merozoite Surface Protein (MSP)-119, (c) IgG against P. falciparum schizont extract, and (d) IgG against P. falciparum MSP-119. The solid line represents the concentration of IgM, or the titer of IgG as compared to the hyper-immune pooled serum (titer = 1). The broken line denotes the upper 95% confidence limit obtained from the baseline, while the mean and confidence interval in the control subjects are denoted as the vertical bar overlapping Y axis.

Cytokines

Interferon (INF) -γ, Interleukin (IL) -1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-12p40, TNF-α were measured, at least in duplicate, using commercial ELISA kits (Diaclone, Besancon). TNF-α showed highly variable values among multiple measurements (data not shown). Among the cytokines examined, IL-12 showed the highest correlation with P. vivax parasitaemia (compare Figure 3a vs Figure 1a). When IL-12 was regressed against the parasitaemia, Prais-Winsten's R2 at half-day time-steps was 0.62 (P < 0.0001). This suggested that IL-12 is closely associated with schizont rupture. IFN-γ was extremely spiky and appeared only in the first few paroxysms (defined as a body temperature above 37.5°C), both in initial and relapse periods (Figure 3b). Other cytokines showed weaker association with paroxysm or parasitaemia (Figure 3c,d,e).

Serum cytokine levels. Concentrations of (a) IL-12, (b) IFN-γ, (c) IL-6, (d) IL-1β, (e) IL-4 (all in pg/ml) (solid lines). The broken line denotes the upper limit of 95% confidence interval obtained from the baseline, while the mean and confidence interval in the control subjects are shown as the vertical bar overlapping Y axis.

Conclusion

Host antibody responses against Plasmodium are heterogeneous across different ethnicities [30], ages and accumulated exposure [31]. A single observation from one volunteer cannot, therefore, be generalized. However, despite this caveat, the present study suggests the possibility that cross-reactive antibodies, especially IgM, in an individual who has been infected only with P. vivax suppress growth of P. falciparum. Although IgM does not undergo a process of affinity maturation, this is compensated for by the fact that it is a pentamer. At least one report found that IgM exhibited a stronger neutralizing effects on Plasmodial merozoites than did IgG [32]. Indeed, this lower specificity may make IgM more likely show cross-species reactivity. The short-lived nature of IgM may also explain why mutual suppression across Plasmodial species is rather transient [6] (also reviewed in [33]), or why immunization with one species rarely protected the vaccinees from other species [34]. In vivo, IgG-mediated cellular mechanisms [9, 35], may also play an important role in the cross-Plasmodium interaction.

IL-12, which showed the highest correlation with P. vivax parasitaemia, is hence likely to be (one of) the most direct mediator(s) bridging from rupturing schizonts to fevers. It was reported that IL-12 and IFN-γ synergistically enhance the parasiticidal activities of peripheral blood mononuclear cells [36–41]. Therefore, the sharp peaks of INF-γ under the presence of IL-12 observed in the volunteer could mount an early in vivo defense against blood-stage parasites, and may contribute to the suppressive effect of P. vivax on P. falciparum.

Collectively, these results suggest a possibility that P. vivax infections may suppress P. falciparum in multiple ways including cross-reactive IgM and cytotoxicity-inducing cytokines. To thoroughly prove that Plasmodium-specific IgM is playing a major role in cross-Plasmodium suppression, such specific IgM should have been purified. Such studies should be part of any further work to test the hypothesis proposed here, preferably within an epidemiologically appropriate framework.

Consent

The present study was approved by the Committee for Ethics, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying information.

Abbreviations

- MSP:

-

Merozoite Surface Protein

- IL:

-

Interleukin.

References

Maitland K, Williams TN, Bennett S, Newbold CI, Peto TE, Viji J, Timothy R, Clegg JB, Weatherall DJ, Bowden DK: The interaction between Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax in children on Espiritu Santo island, Vanuatu. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996, 90: 614-620. 10.1016/S0035-9203(96)90406-X.

Luxemburger C, Ricci F, Nosten F, Raimond D, Bathet S, White NJ: The epidemiology of severe malaria in an area of low transmission in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997, 91: 256-262. 10.1016/S0035-9203(97)90066-3.

Boyd MK, Kitchen SF: Veneral vivax activity in persons simultaneously inoculated with Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med. 1938, 18: 505-514.

Pukrittayakamee S, Vanijanonta S, Chantra A, Clemens R, White NJ: Blood stage antimalarial efficacy of primaquine in Plasmodium vivax malaria. J Infect Dis. 1994, 169: 932-935.

Black J, Hommel M, Snounou G, Pinder M: Mixed infections with Plasmodium falciparum and P. malariae and fever in malaria. Lancet. 1994, 343: 1095-10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90203-8.

Bruce MC, Donnelly CA, Alpers MP, Galinski MR, Barnwell JW, Walliker D, Day KP: Cross-species interactions between malaria parasites in humans. Science. 2000, 287: 845-848. 10.1126/science.287.5454.845.

Mayxay M, Pukritrayakamee S, Chotivanich K, Imwong M, Looareesuwan S, White NJ: Identification of cryptic coinfection with Plasmodium falciparum in patients presenting with vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 65: 588-592.

Nagao Y, Dachlan YP, Soedarto , Hidajati S, Yotopranoto S, Kusmartisnawati , Subekti S, Ideham B, Tsuda Y, Kawabata M: Distribution of two species of malaria, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, on Lombok Island, Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2003, 34: 495-500.

Druilhe P, Sabchareon A, Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Oeuvray C, Perignon JL: In vivo veritas: lessons from immunoglobulin-transfer experiments in malaria patients. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997, 91 (Supplement 1): S37-S53. 10.1080/00034989761292.

Price RN, Simpson JA, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Hkirjaroen L, ter Kuile F, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, White NJ: Factors contributing to anemia after uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 65: 614-622.

White NJ: Malaria. Manson's Tropical Diseases. Edited by: Cook GC. 2003, Zumla AI: W. B. SAUNDERS, 21

Mayxay M, Pukrittayakamee S, Newton PN, White NJ: Mixed-species malaria infections in humans. Trends Parasitol. 2004, 20: 233-240. 10.1016/j.pt.2004.03.006.

Snounou G, White NJ: The co-existence of Plasmodium: sidelights from falciparum and vivax malaria in Thailand. Trends Parasitol. 2004, 20: 333-339. 10.1016/j.pt.2004.05.004.

Alles HK, Mendis KN, Carter R: Malaria mortality rates in South Asia and in Africa: implications for malaria control. Parasitol Today. 1998, 14: 369-375. 10.1016/S0169-4758(98)01296-4.

Adjuik M, Smith T, Clark S, Todd J, Garrib A, Kinfu Y, Kahn K, Mola M, Ashraf A, Masanja H: Cause-specific mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa and Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 2006, 84: 181-188. 10.2471/BLT.05.026492.

Guerra CA, Hay SI, Lucioparedes LS, Gikandi PW, Tatem AJ, Noor AM, Snow RW: Assembling a global database of malaria parasite prevalence for the Malaria Atlas Project. Malar J. 2007, 6: 17-10.1186/1475-2875-6-17.

Richie TL: Interactions between malaria parasites infecting the same vertebrate host. Parasitology. 1988, 96 (Pt 3): 607-639.

Mason DP, McKenzie FE, Bossert WH: The blood-stage dynamics of mixed Plasmodium malariae-Plasmodium falciparum infections. J Theor Biol. 1999, 198: 549-566. 10.1006/jtbi.1999.0932.

Mason DP, McKenzie FE: Blood-stage dynamics and clinical implications of mixed Plasmodium vivax-Plasmodium falciparum infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 61: 367-374.

Jonas H: Philosophical reflections on experimenting with human subjects. Daedalus. 1969, 98: 219-247.

Nagao Y, Chavalitshewinkoon-Petmitr P, Noedl H, Thongrungkiat S, Krudsood S, Sukthana Y, Nacher M, Wilairatana P, Looareesuwan S: Paroxysm serum from a case of Plasmodium vivax malaria inhibits the maturation of P. falciparum schizonts in vitro. Ann Trop Med Parasit. 2003, 97: 587-592. 10.1179/000349803225001409.

Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN: High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993, 61: 315-320. 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-B.

Saux MC, Mosser J, Pontagnier H, Leng B: Pharmacokinetic study of doxycycline polyphosphate (PPD), hydrochloride (CHD) and base (DB). Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1981, 6: 3-10.

Duc DD, de Vries PJ, Nguyen XK, Le Nguyen B, Kager PA, van Boxtel CJ: The pharmacokinetics of a single dose of artemisinin in healthy Vietnamese subjects. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994, 51: 785-790.

Trager W, Lanners HN: Initial extracellular development in vitro of merozoites of Plasmodium falciparum. J Protozool. 1984, 31: 562-567.

Okech BA, Corran PH, Todd J, Joynson-Hicks A, Uthaipibull C, Egwang TG, Holder AA, Riley EM: Fine specificity of serum antibodies to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein, PfMSP-1(19), predicts protection from malaria infection and high-density parasitemia. Infect Immun. 2004, 72: 1557-1567. 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1557-1567.2004.

Newman KC, Korbel DS, Hafalla JC, Riley EM: Cross-talk with myeloid accessory cells regulates human natural killer cell interferon-gamma responses to malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2: e118-10.1371/journal.ppat.0020118.

Burghaus PA, Holder AA: Expression of the 19-kilodalton carboxy-terminal fragment of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in Escherichia coli as a correctly folded protein. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994, 64: 165-169. 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90144-9.

Prais SJ, Winsten CB: Trend Estimators and Serial Correlation. 1954, Chicago: Cowles Commission Discussion Paper

Bolad A, Farouk SE, Israelsson E, Dolo A, Doumbo OK, Nebie I, Maiga B, Kouriba B, Luoni G, Sirima BS: Distinct interethnic differences in immunoglobulin G class/subclass and immunoglobulin M antibody responses to malaria antigens but not in immunoglobulin G responses to nonmalarial antigens in sympatric tribes living in West Africa. Scand J Immunol. 2005, 61: 380-386. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01587.x.

Tongren JE, Drakeley CJ, McDonald SL, Reyburn HG, Manjurano A, Nkya WM, Lemnge MM, Gowda CD, Todd JE, Corran PH, Riley EM: Target antigen, age, and duration of antigen exposure independently regulate immunoglobulin G subclass switching in malaria. Infect Immun. 2006, 74: 257-264. 10.1128/IAI.74.1.257-264.2006.

Couper KN, Phillips RS, Brombacher F, Alexander J: Parasite-specific IgM plays a significant role in the protective immune response to asexual erythrocytic stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection. Parasite Immunol. 2005, 27: 171-180. 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00760.x.

Butcher G: Cross-species Immunity in Malaria. Parasitol Today. 1998, 14: 166-10.1016/S0169-4758(97)01189-7.

Butcher GA, Mitchell GH, Cohen S: Antibody mediated mechanisms of immunity to malaria induced by vaccination with Plasmodium knowlesi merozoites. Immunology. 1978, 34: 77-86.

Roussilhon C, Oeuvray C, Muller-Graf C, Tall A, Rogier C, Trape JF, Theisen M, Balde A, Perignon JL, Druilhe P: Long-term clinical protection from falciparum malaria is strongly associated with IgG3 antibodies to merozoite surface protein 3. PLoS Med. 2007, 4: e320-10.1371/journal.pmed.0040320.

Favre N, Ryffel B, Bordmann G, Rudin W: The course of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infections in interferon-gamma receptor deficient mice. Parasite Immunol. 1997, 19: 375-383. 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1997.d01-227.x.

De Souza JB, Williamson KH, Otani T, Playfair JH: Early gamma interferon responses in lethal and nonlethal murine blood-stage malaria. Infect Immun. 1997, 65: 1593-1598.

Choudhury HR, Sheikh NA, Bancroft GJ, Katz DR, De Souza JB: Early nonspecific immune responses and immunity to blood-stage nonlethal Plasmodium yoelii malaria. Infect Immun. 2000, 68: 6127-6132. 10.1128/IAI.68.11.6127-6132.2000.

Rhee MS, Akanmori BD, Waterfall M, Riley EM: Changes in cytokine production associated with acquired immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001, 126: 503-510. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01681.x.

Dodoo D, Omer FM, Todd J, Akanmori BD, Koram KA, Riley EM: Absolute levels and ratios of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine production in vitro predict clinical immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2002, 185: 971-979. 10.1086/339408.

Artavanis-Tsakonas K, Riley EM: Innate immune response to malaria: rapid induction of IFN-gamma from human NK cells by live Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. J Immunol. 2002, 169: 2956-2963.

Acknowledgements

Most of the immunological experiments in the study were conducted with the assistance by Eleanor Riley, Patrick Corran, John G Raynes, and Jackie Cook. The corresponding author requested these researchers for their cooperation after 2003. The authors are grateful to Akira Kaneko, Colin Sutherland, Taro Kinoshita, Yusuke Maeda, Wouter Hazenbos, Noriko Fujiwara, and Pattra Suntornthiticharoen for their assistance and advice. The authors thank the staff of the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Mahidol University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YN conceived this study, and asked other authors to participate in this study, MKS assumed responsibility for PCR, PCP and PT assisted in P. falciparum cultures, ST prepared the infected mosquitoes, SK and PW assumed the responsibility for the clinical management of YN, JBS assisted in immunological measurements, TI assisted in PCR and measurements of cytokines, SL organized the entire study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagao, Y., Kimura-Sato, M., Chavalitshewinkoon-Petmitr, P. et al. Suppression of Plasmodium falciparum by serum collected from a case of Plasmodium vivax infection. Malar J 7, 113 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-113

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-113