Abstract

Background

The objective of the present study was to identify the effects and relative importance of demographic factors and psychosocial stressors on self-esteem of psychiatric patients.

Method

The present study was carried out on a consecutive sample of 1,190 individuals attending an open-access psychiatric outpatient clinic. Patients were diagnosed according to DSM III-R diagnostic criteria following detailed assessments. At screening, patients and controls completed two self-esteem questionnaires, the Rosenberg self-esteem scale and the Janis and Field Social Adequacy scale. In addition, a large amount of demographic and psychosocial data was collected on all patients.

Results

Significantly increased self-esteem was observed with an increase in age, educational achievement and income. Employed patients showed significantly higher self-esteem compared to unemployed patients. Female patients had a significantly lower self-esteem compared to male patients. The self-esteem of psychiatric patients did not vary significantly with their marital status. No relationship was detected between acute stressors and the self-esteem of psychiatric patients, although severe enduring stressors were associated with lower self-esteem in psychiatric patients.

Conclusion

The results of this large study demonstrate that the self-esteem of adult psychiatric patients is affected by a number of demographic and psychosocial factors including age, sex, educational status, income, employment status, and enduring psychosocial stressors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Previous research in non-psychiatric populations has shown that self-esteem is related to a number of demographic factors such as sex [1–4], age [1, 5–8], marital status [9, 10], educational status [11–20], and income [21–23]. Self-esteem is also related to various psychosocial factors, including life events [24–26], social support [27–29], and delinquency [30–34]. However, sometimes these findings have not been consistent between studies. For example, while a majority of researchers [1–4] have reported higher global self-esteem in men compared to women, others have not found these differences [35, 36].

Nonetheless, since previous research mostly has been carried out in non-psychiatric populations, it is uncertain how relevant these findings are to psychiatric patients. This is important since lowered self-esteem is recognised to occur in several psychiatric disorders, particularly depressive disorders [37, 38], eating disorders [39–41], and alcohol and drug use disorders [42–48]. Indeed, it has been proposed that lowered self-esteem is an important etiological determinant in the development of each of these disorders [26, 28, 49–51]. Therefore, it is of considerable interest to determine which factors are associated with lowered self-esteem in psychiatric patients.

The current study has been designed to explore the relationship between self-esteem and a number of demographic and psychosocial factors in a large sample of psychiatric outpatients, with the aim of clarifying the relative strength of each of these associations.

Method

Population Sample

The current study was carried out on data collected on a consecutive sample of 1,190 cases attending a psychiatric open access clinic over a one-year period. In this clinic patients can refer themselves or be referred through a family doctor. The sample consisted of 957 psychiatric patients, 182 cases with conditions not attributable to a mental disorder but who had psychosical stressor (the "psychosocial stressor" group, also termed "V-codes" in DSM-III R), and 51 healthy individuals who accompanied patients and were themselves assessed but did not receive a psychiatric diagnosis (controls).

At the clinic, a therapist, who is a psychologist, a social worker or a psychiatric nurse, sees each patient. Any diagnoses made are then confirmed during a subsequent interview with a psychiatrist, with a final consensus diagnosis being made according to DSM III-R criteria. It is the practice in the clinic that patient's accompany, particularly family members, may be assessed. As part of the assessment, all attendants completed a questionnaire containing two self-esteem scales (see below). Demographic information such as age, sex, marital status, income, level of education, and current employment status, as well as the scores on the two self-esteem scales was collected from the questionnaire. Information regarding personality disorders, developmental disorders, and severity of psychosocial stressors was collected from the patients' files. The gathered data from patients and control subjects was analysed separately.

Self-Esteem Scales

Two well-recognised patient-completed questionnaires were used to measure self-esteem. These were the Janis and Field Social Adequacy Scale (JF Scale) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg Scale). The JF Scale consists of 23 self-rating items, which measure anxiety in social situations, self-consciousness, and feelings of personal worthlessness. The maximum score is 115, and a higher score reflects increased self-esteem. Reliability estimates based on the Spearman-Brown formula and split-half reliability estimates for this scale are 0.91 and 0.83, respectively.

The Rosenberg Scale measures global self-esteem and personal worthlessness. It includes 10 general statements assessing the degree to which respondents are satisfied with their lives and feel good about themselves. In contrast to the JF Scale, a decreased score reflects increased self-esteem. In the original report, Rosenberg quoted a reproducibility of 0.9 and a scalability of 0.7. The Rosenberg Scale has previously been validated in other studies [52, 53]. It is the most widely used scale to measure global self-esteem in research studies.

These two scales differ from each other in that the JF Scale measures multidimensional self-concept, while the Rosenberg Scale measures global self-esteem.

Statistical Methods

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the data. The two measures of self-esteem were considered as dependent variables, and all other variables, such as age, sex, income, and history of alcohol abuse were considered independent variables or factors. If the result of one way ANOVA showed statistically significant difference between means of the groups, the Student-Newman-Keuls test for multiple comparisons was applied. The Levene test was used to examine the homogeneity of variances, a main assumption in ANOVA.

Multifactorial ANOVA, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and Pearson correlation coefficients, was also applied in some cases. Multifactorial ANOVA was applied to control the variances related to the other factors and to measure interaction between the factors. ANCOVA is an extension of ANOVA that allows the removal of additional sources of variation from the error term, thus enhancing the power of the analysis. This test is also used to control for the effects of a third variable (covariate). Pearson correlation coefficient was used to quantify the relationship between two or more variables. It measures the strength and indicates the direction of the relationship [54].

Results

Correlation between Self-Esteem Scales

In the current study, the correlation coefficient between the two self-esteem scales was -0.72. This strong correlation between two scales suggests that they measure similar overlapping concepts.

Age

The sample was grouped into seven age categories (<18; 19–24; 25–30; 31–40; 41–50; 51–59; >60). The results showed statistically significant differences between these groups with both the JF Scale (F6,889 = 4.65, p < 0.0001) and the Rosenberg scale (F6,825 = 5.00, p < 0.0001). The results showed a general pattern of increase in self-esteem with age (Figure 1). With both scales, those aged more than 60 showed statistically significantly higher self-esteem than those aged less than 50 (p < 0.05). Those aged 51–59 also had significantly higher self-esteem than those groups aged 25–30 and 31–40 (p < 0.05). With the JF Scale, however, the youngest age group (<18) had significantly higher self-esteem than those aged 19–24 and those aged 25–30 (p < 0.05). Since a large portion of patients had depressive disorders, the effect of age on self-esteem was evaluated in sub groups of depressed and non-depressed patients. Similar pattern of increase of self-esteem with age was observed as total sample of patients.

Gender

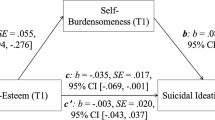

The sample of patients was divided into two groups of males and females. Female patients had significantly lower self-esteem compared to males on both the JF scale (mean in females 59.50 ± 18.72 vs. 65.93 ± 18.23 in males; F1,847 = 24.91, p < 0.0001) and the Rosenberg scale (mean in females 5.22 ± 2.91 vs. 4.71 ± 2.81 in males; F1,785 = 6.17, p < 0.01).

Since depressed patients formed a large portion of the sample, the sample was divided into non-depressed and depressed patients. Similar pattern was observed in either of the two subgroups. Compared to the non-depressed groups, self-esteem was lower in depressed females with both the JF scale (F1,413 = 12.55, p < 0.001) and the Rosenberg scale (F1,384 = 6.22, p < 0.01) (Figure 2). Depressed females had a significantly lower self-esteem than depressed males with the JF scale (F1,434 = 5.68, p < 0.02), but the difference did not reach statistical significance with the Rosenberg scale (F1,401 = 0.013, p= 0.91).

Gender and Self-Esteem. This shows the differences in self-esteem between males and female patients for all psychiatric patients, and also when this sample is divided into depressed patients and non-depressed patients. The female depressed patients have significantly lower self-esteem than the non-depressed patients as measured by both the JF-Scale (2A) and the Rosenberg Scale (2B). * = p < 0.05

Marital Status

The patients' marital status was assigned to one of seven groups, namely never married, married, separated, divorced, widowed, common-law, and other status. No two groups were significantly different at the 0.05 level of significance on the JF Scale. However, with the Rosenberg scale, married patients had significantly higher self-esteem compared to never married patients (F6,776 = 2.71, p < 0.01). The difference did not remain significant after adjusting for age with ANCOVA (F6,775 = 0.77, p = 0.59). Thus, our study does not demonstrate that marital status affected the self-esteem of psychiatric patients.

Educational Status

The patients were divided into five groups according to their educational achievement (group 1 = grade <10; group 2 = grade 10–11; group 3 = high school graduate; group 4 = technical school or equivalent qualification; and group 5 = university degree or equivalent). The results of the Rosenberg scale showed that the patients in groups 4 and 5 had significantly higher self-esteems than those in groups 1 and 2 (F4,763 = 5.51, p < 0.001) (Figure 3). The difference between groups on this scale remained statistically significant after adjusting for age with ANCOVA (p < 0.001). Although the same trend was observed when using the JF Scale, none of the differences between the groups reached statistical significance.

Educational Achievement and Self-Esteem. The patients were divided into five groups according to their educational achievement (Less than Grade 10, Grade 10 – 11, Grade 12, Technical School or Equivalent, University Degree). The results of the Rosenberg scale showed that the patients in the latter two groups had significantly higher self-esteems than those in groups 1 and 2. * = p < 0.05

Employment Status

Patients were divided into six groups according to their employment status (employed full time; employed part time; housewife or househusband; unemployed; student; retired). The results of the JF scale showed that retired patients on average had significantly higher self-esteem compared to other groups (F5,832 = 2.48, p < 0.05). However, this difference did not remain statistically significant after adjusting for age (P = 0.19). With the Rosenberg scale employed patients had a significantly higher self-esteem than unemployed patients (F5,772 = 3.97, p < 0.01) This difference remained statistically significant after adjusting for age using ANCOVA (p < 0.05) or adjusting for sex using two way ANOVA (p < 0.05). Of interest was the finding that employed patients had significantly higher self-esteem compared to patients who were students (p < 0.05).

Personal Income

Patients were divided into eight groups according to their level of annual income (group 1 = $0–$4999; group 2 = $5000–$9999; group 3 = $10,000–$14,999; group 4 = $15,000–$19,999; group 5 = $20,000–$29,999; group 6 = $30,000–$39,999; group 7 = $40,000–$49,999; and group 8>$50,000). The results showed a significant difference between groups on the JF Scale (F7,738 = 2.47, p < 0.02). However, further probing with the Student-Newman-Keuls test indicated that no two groups were significantly different at the 0.05 level of significance. With the Rosenberg scale, patients with annual income of $40,000 to $49,000 had significantly higher self-esteem than patients whose annual income was less than $20,000 (F7,689 = 3.91, p < 0.001) (Figure 4). The correlation coefficients between income and either of the scales was low, but statistically significant (r1 for the JF scale was 0.11, p < 0.01; r2 for the Rosenberg scale was -0.16, p < 0.001). These findings suggest a possible weak relationship between self-esteem of psychiatric patients and personal income.

Family Income

With the JF scale scores there were no significant differences between groups. With the Rosenberg scale, patients whose annual family income was between $40,000 to $50,000 showed significantly higher self-esteem than those with an annual family income of less than $5,000 (F7,660 = 2.37, P = 0.02). The correlation coefficients between family income and either scales were low, but statistically significant (r1 for the JF scale was 0.11, p < 0.01; r2 for the Rosenberg scale was -0.15, p < 0.001). Again, these findings suggest a possible weak relationship between self-esteem of psychiatric patients and family income.

Psychosocial Stressors – Acute and Chronic

Psychiatric patients were divided into five groups based upon the severity of their acute psychosocial stressors as recorded at their initial interview. These five levels were none, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme. The results of ANOVA showed no statistically significant difference between any of these groups, for either scale.

Patients were also divided into the same five groups based on the severity of enduring psychosocial stressors, as assessed at their initial interview. The results of the JF scale show no statistically significant difference between the groups (F4,831 = 1.64, p = 0.15). However, with the Rosenberg scale, patients who experienced severe or extreme enduring stressors had significantly lower self-esteem than patients who experienced none, mild, or moderate enduring stressors (F4,774 = 3.44, p = 0.004).

Presence of Psychiatric Disorders

The level of self-esteem was compared between normal and psychiatric patients. Psychiatric patients had significantly lower self-esteem compared to controls (p < 0.001). The amount by which self-esteem was lowered differed significantly between different diagnostic groups. However, presence of any psychiatric disorders lowered self-esteem.

Relative Importance of Different Factors

Significant difference at the 0.05 level of significance was observed for four factors on both scales of self-esteem: presence of psychiatric disorder, age, sex, and educational status. To compare the amount of variance due to each factor, multifactorial analysis of variance was performed. Among these factors, the factors of presence of psychiatric disorder and age had the strongest effect with both the JF scale (p < 0.001) and Rosenberg scale (p < 0.001). On the basis of their relative strength, the remaining factors are ranked in a decreasing order as sex (p < 0.001), and educational status (p = 0.01) for the JF scale, and educational status (p = 0.003) and sex (p = 0.007) for the Rosenberg scale.

Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between self-esteem and several demographic and psychosocial factors in psychiatric patients. This is the largest study to date in psychiatric patients and is unique in using more than a single scale to assess self-esteem in multiple psychiatric diagnoses. Nonetheless, before discussing the results it is important to mention that some of the measured factors, such as severity of psychosocial stressors, educational status, and employment status were assessed on non-standardized scales. Thus, the applicability of these results in other populations may be uncertain.

Self-Esteem and Age

In non-psychiatric populations, it is clear that self-esteem is stable over long periods, in a similar manner to personality traits [55]. It has also been shown that self-esteem is correlated with age, although the exact relationship between self-esteem and age is uncertain. While Bloom [5] found a curvilinear relationship between age and self-esteem, with self-esteem reaching a peak in the 40–49 age group, most other researchers have found self-esteem to remain relatively stable or to increase at older ages [6, 7]. Consistent with these studies, a general pattern of increase of self-esteem with age was observed in psychiatric patients that seem to be independent on type of their disorders.

Self-Esteem and Gender

There is a substantial literature in non-psychiatric patients showing that males have a higher self-esteem than females (e.g., 1–3). It is not clear if this difference is a trait, is related to the cultural aspects of society, or is a combination of several factors. Cultural factors are likely to play some role at least, since over the past 30 years the self-esteem of women appears to be decreasing [56]. Most researchers do not believe that these observed difference between self-esteem of males and females are inherent. The observed difference has been explained in several ways, including the way parents and teachers train and nurture children [57], the way parents communicate with each other [58], the expectations of society regarding the definition of what makes a successful man or woman [59], and the different social roles for males and females [60, 61]. It has been suggested that the differences between the self-esteem of males and females are likely to diminish as views about women and men's roles continue to change [20]. However, there are no longitudinal studies examining whether the self-esteem of women has changed during the last few decades.

In terms of psychiatric patients, our findings show that male patients had higher levels of self-esteem than females. This difference was less prominent when patients had a major depressive disorder, presumably due to the effects of the depressive disorder itself on self-esteem which dampen the observed self-esteem differences in non-depressed patients.

Self-Esteem and Marital Status

A previous study has reported significantly lower global self-esteem in divorced or separated mothers, compared to married mothers [62]. In contrast, we found that the self-esteem of the psychiatric patients in our sample was not affected by their marital status. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear. However, we propose that marital status today have less effect on self-esteem than it once had due to a change in society's attitude towards divorce.

Self-Esteem and Education

Low self-esteem has been associated with poor academic experiences [17]. On the other hand, higher levels of educational attainment lead to higher status jobs and indirectly have been felt to have a positive impact on self-esteem [20]. Therefore, higher educational attainment may have a direct impact on self-esteem or an indirect effect via higher occupational status or financial status usually accompanying the higher educational attainment.

The results of the present study showed that patients with higher educational attainment had higher self-esteem compared to those with lower educational attainment. This finding supports the relationship between greater educational achievement and higher self-esteem.

Current Employment Status and Self-Esteem

Although there are many confounding variables such as age, previous occupational status, and degree of social support, generally a significant correlation has been found between low self-esteem and unemployment in non-psychiatric population [20, 63, 64]. Similarly, the results of the present study show that employed patients had significantly higher self-esteem compared to unemployed patients. Since the self-esteem of students was significantly lower than that of employed patients, it is possible that the factor of employment reflect the effects of financial security, respect, social position, and prestige on the self-esteem of individuals. It has also been found that in psychiatric patients self-esteem is significantly affected by job satisfaction [65].

Self-Esteem and Income

There has been some previous work, particularly in women, suggesting that higher income is associated with higher self-esteem [66, 67]. The findings from the present study suggest that patients with higher personal income, as well as those with higher family income, tend to have higher self-esteem compared to patients with low family or personal income. However, it should be noted that these differences were only significant with one of the two self-esteem measures, and between the groups on the opposite ends of the income scale. Thus, our findings do not lend strong support to suggestions that income strongly affects self-esteem in psychiatric patients.

Self-Esteem and Psychosocial Stressors

Most researchers agree that there is a complex link between self-esteem and psychosocial stressors. Low self-esteem, at least in part, is related to adverse social circumstances such as unemployment [23, 63] and life stressors such as divorce [65]. Different studies reported that negative interaction with family members, lack of close confiding relationship, and early loss of mother or early inadequate parenting were associated with lower self-esteem [9, 69, 70]. On the other hand, positive life changes can lead to higher self-esteem [26].

In the present study, we considered two aspects of psychosocial stressors on the self-esteem of psychiatric patients, their onset and their severity. Interestingly, our results demonstrate that acute psychosocial stressors had no significant effect on the self-esteem of patients. However, the longer the severe stressor, the more destructive the effects are on self-esteem. This was shown by the finding that patients who experienced extreme or severe enduring psychosocial stressors had significantly lower self-esteem than those not experiencing such stressors. In a similar manner, low self-esteem may impact unhealthy lifestyles [71], which itself can also increase psychosocial stressors.

Conclusion

We found that many factors are related to lowered self-esteem in psychiatric patients. Of these, the most significant were the presence of a psychiatric disorder, the exact psychiatric diagnosis, the age of the patients, and the gender of the patient. Educational achievement, income, and employment status also had effects on the self-esteem of psychiatric patients. However, it is hard to separate these latter effects from each other. Among other factors, marital status had little or no effect on self-esteem. We also found that severe enduring psychosocial stressors had an effect on self-esteem. In general, we found that the effects of the demographic factors and psychosocial stressors on the self-esteem of psychiatric patients were similar to their effects on self-esteem of the non-psychiatric population reported in the literature.

References

Hong S, Bianca M: Self-esteem: the effects of life satisfaction, sex, and age. 1. Psychol Rep. 1993, 72: 95-101.

O'Brien EJ: Sex differences in components of self-esteem. Psychol Rep. 1991, 68: 241-265.

Berger CR: Sex differences related to self-esteem factor structure. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1968, 32: 442-446.

Feather NT: Masculinity, femininity, self-esteem and subclinical depression. Sex-Roles. 1985, 12: 491-500.

Bloom KL: Age and the self-concept. Am J Psychiatry. 1961, 118: 534-538.

Gove WR, Ortega ST, Briggs Style C: The Maturational and role perspectives on aging and self through the adult years: an empirical evaluation. Am J Sociology. 1989, 94: 1117-1145.

Coleman PG, Ivani-Chalian C, Robindon M: Self-esteem and its sources: stability and change in later life. Aging and Society. 1993, 13: 171-192.

Brandtstadter J, Greve W: Explaining the resilience of the aging self: reply to Carstensen and Freund. Dev Rev. 1994, 14: 93-102.

Brown GW, Bifulco A, Veiel H, Andrews B: Self-esteem and depression. II: Social correlates of self-esteem. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990, 25: 225-234.

Rutter M: Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1987, 57: 316-331.

Morrison TL, Thomas MD, Weaver J: Self-esteem and self-estimates of academic performance. J Consul Clin Psychol. 1973, 41: 412-415.

Sigall H, Gould R: The effects of self-esteem and evaluator demandingness on effort expenditure. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1977, 35: 12-20.

Hoge DR, Smith EK, Crist JT: Reciprocal effects of self-concept and academic achievement in sixth and seventh grades. J Youth Adolesc. 1995, 24: 295-314.

Skaalvik EM, Hagtvet KA: Academic achievement and self-concept: an analysis of causal predominance in a developmental prospective. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990, 58: 292-307.

Hansford BC, Hattie JA: The relationship between self and achievement/ performance measures. Rev Educ Res. 1982, 52: 123-142.

West CK, Fish JA, Stevens RJ: General self-concept, self-concept of academic ability and school achievement: implication for 'causes' of self-concept. Austral J Educ. 1980, 24: 194-213.

Slomkowski C, Klein RG, Mannuzza S: Is self-esteem an important outcome in hyperactive children?. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1995, 23: 303-315.

Muijs RD: Symposium Self-perception and performance: Predictors of academic achievement and academic self-concept: a longitudinal perspective. Br J Educ Psychol. 1997, 67: 263-277.

Marsh HW: Causal ordering of academic self-concept and academic achievement: a multiwave, longitudinal panel analysis. J Educ Psychol. 1990, 82: 646-656.

Bachman JG, O'Malley PM: Self-esteem in young men: A longitudinal analysis of the impact of educational and occupational attainment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1977, 35: 365-380.

Diener E, Diener M: Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. J Personality and Soc Psychol. 1995, 68: 653-663.

Mueser KT, Becker DR, Torrey WC, Xie H., Bond GR, Drake RE, Dain BJ: Work and nonvocational domains of functioning in persons with severe mental illness: a longitudinal analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997, 185: 419-26.

Warr P, Jackson P: Self-esteem and unemployment among young workers. Le Travail Humain. 1983, 46: 355-366.

Miller PMcC, Kreitman NB, Ingham JG, Sashidharan SP: Self-esteem, life stress and psychiatric disorder. J Affect Disord. 1989, 17: 65-75.

Brown GW, Andrews B, Harris T, Adler Z, Bridge L: Social support, self-esteem and depression. Psychol Med. 1986, 16: 813-831.

Brown GW, Adler Z, Bifulco A: Life events, difficulties and recovery from chronic depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1988, 152: 487-498.

Brown GW, Andrews B, Bifulco A, Veiel HOF: Self-esteem and depression. I: Measurement issues and prediction of onset. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990, 25: 200-209.

Brown GW, Bifulco A, Andrews B: Self-esteem and depression. III: Etiological issues. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990, 25: 235-243.

Brown GW, Bifulco A, Andrews B: Self-esteem and depression. IV: Effects on course and recovery. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990, 25: 244-249.

Berman SM: Validation of social self-esteem and an experimental index of delinquent behaviour. Percept Mot Skills. 1976, 43: 847-850.

Rice F: The adolescent: development, relationships, and culture. Boston, Allyn and Bacon. 1992

Gordon WR, Caltabiano ML: Urban-rural differences in adolescent self-esteem, leisure boredom, and sensation-seeking as predictors of leisure-time usage and satisfaction. Adolescence. 1996, 31: 883-901.

Schweitzer R, Seth-Smith M, Callan V: The relationship between self-esteem and psychological adjustment in young adolescents. J Adolescence. 1992, 15: 83-97.

Heaven PCL: Personality and self-reported delinquency: a longitudinal analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996, 37: 747-751.

Ryff CD: Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989, 57: 1069-1081.

Richardson TM, Benbow CP: Long-term effects of acceleration on the social-emotional adjustment of mathematically precocious youths. J Educ Psychol. 1990, 82: 464-470.

Ryan ND, Puig-Antich J, Ambrosini P: The clinical picture of major depression in children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987, 36: 698-700.

Battle J: Relationship between self-esteem and depression. Psychol Rep. 1978, 42: 745-746.

Baird P, Sights JRL: Low self-esteem as a treatment issue in the psychotherapy of anorexia and bulimia. J Counselling Development. 1986, 64: 449-451.

Walters EE, Kendler KS: Anorexia nervosa and anorexic-like syndromes in a population-based female twin sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1995, 152: 64-71.

Kendler KS, MacLean C, Neale M, Kessler R, Health A, Eaves L: The genetic epidemiology of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1991, 148: 1627-1637.

Chafetz ME, Blane HT, Hill MJ: Frontiers of alcoholism. New York, Science House. 1970

Clinebell HJ: Understanding and counselling the alcoholic through religion and psychology. Nashville, Abingdon Press. 1968

Sands PM, Hanson PG, Sheldon RB: Recurring themes in group psychotherapy with alcoholics. Psychiatr Q. 1967, 41: 474-482.

Young M, Wrech CE, Bakema D: Area specific self-esteem scales and substance use among elementary and middle school children. J Sch Health. 1989, 59: 251-254.

Botvin GJ: Substance abuse prevention research: Recent developments and future directions. J Sch Health. 1986, 56: 369-374.

Allendorf S, Sunseri AJ, Cullinan J, Oman JK: Student heart health knowledge, smoking attitudes and self-esteem. J Sch Health. 1985, 55: 196-199.

Perez R, Padilla AM, Ramirez A: Correlates and changes over time in drug and alcohol use within a barrio population. Amer J Common Psychiatry. 1980, 8: 621-636.

Silverstone PH: Low self-esteem in eating disordered patients in the absence of depression. Psychol Rep. 1990, 67: 276-278.

Kaplan HB: Self-attitudes and deviant behavior. Pacific Palisades, CA, Goodyear. 1975

Kaplan HB: Deviant behavior in defence of self. New York, Academic Press. 1980

Hagborg W: The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and Harter's Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents: A concurrent validity study. Psychol School. 1993, 30: 132-136.

Fleming J, Courtney B: The dimensionality of self-esteem II: Hierarchical facets model for revised measurement scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1984, 46: 404-421.

Munro BH, Page EB: Statistical methods for health care research. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. 1993

Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Robins RW: Stability of self-esteem across the life span. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003, 84: 205-220.

Sondhaus EL, Kurtz RM, Strube MJ: Body attitude, gender, and self-concept: a 30-year perspective. J Psychol. 2001, 135: 413-429.

Hechtman L, Weiss G, Perlman T: Hyperactives as young adults. Can J Psychiatry. 1980, 25: 478-483.

Matteson R: Adolescent self-esteem, family communication, and marital satisfaction. J Psychol. 1974, 86: 35-47.

Bardwick J: The psychology of women. New York: Harper & Row. 1971

Meddin JR: Sex differences in depression and satisfaction with self: findings from a United States national survey. Soc Sci Med. 1986, 22: 807-812.

Gove WR: Sex, marital status and suicide. J Health Soc Behav. 1972, 13: 204-213.

Tcheng-Laroche F, Prince R: Separated and divorced women compared with married controls. Soc Sci Med. 1983, 17: 95-105.

Feather NT: Unemployment and its social correlates: a study of depressive symptoms, self-esteem, protestant ethic values, attributional style and apathy. Aust J Psychol. 1982, 34: 309-323.

Shams M, Jackson PR: The impact of unemployment on the psychological well-being of British Asians. Psychol Med. 1994, 24: 347-55.

Casper ES, Fishbein S: Job satisfaction and job success as moderators of the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002, 26: 33-42.

Brown GW, Bifulco A: Motherhood, employment and the development of depression: A replication of a finding?. Br J Psychiatry. 1990, 156: 169-179.

Keith PM, Schafer RB: Depression in one-and-two job families. Psychol Rep. 1980, 47: 669-670.

Holmes TH, Rahe RH: The social rating scale. J Psychosomatol Res. 1967, 11: 213-218.

Ingham JG, Kreitman NB, Miller P, Sashidharan SP, Surtees PG: Self-esteem, vulnerability and psychiatric disorder in the community. Br J Psychiatry. 1986, 148: 375-385.

Brown GW, Harris TO: Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. London, Tavistock. 1978

Johnson RL: The relationships among racial identity, self-esteem, sociodemographics, and health-promoting lifestyles. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2002, 16: 193-207.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Salsali, M., Silverstone, P.H. Low self-esteem and psychiatric patients: Part II – The relationship between self-esteem and demographic factors and psychosocial stressors in psychiatric patients. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2, 3 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2832-2-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2832-2-3