Abstract

Background

Evaluation of evidence for the effectiveness of implementation strategies aimed at reducing prescriptions for the use of acid suppressive drugs (ASD).

Methods

A systematic review of intervention studies with a design according to research quality criteria and outcomes related to the effect of reduction of ASD medication retrieved from Medline, Embase and the Cochrane Library. Outcome measures were the strategy of intervention, quality of methodology and results of treatment to differences of ASD prescriptions and costs.

Results

The intervention varied from a single passive method to multiple active interactions with GPs. Reports of study quality had shortcomings on subjects of data-analysis. Not all outcomes were calculated but if so rction of prescriptions varied from 8% up to 40% and the cost effectiveness was in some cases negative and in others positive. Few studies demonstrated good effects from the interventions to reduce ASD.

Conclusion

Poor quality of some studies is limiting the evidence for effective interventions. Also it is difficult to compare cost-effectiveness between studies. However, RCT studies demonstrate that active interventions are required to reduce ASD volume. Larger multi-intervention studies are necessary to evaluate the most successful intervention instruments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Analysis of the use of dyspeptic medication demonstrate that acid-suppressive drugs (ASD) are prescribed in 10% of the population each year [1–3]. Three percent of these patients are chronic users (>180 DDD), mostly of Proton-Pump Inhibitors (PPI), of which prescriptions increase 5% every year [4, 5]. Together dyspeptic patients account for almost 11% of the pharmaceutical budget of the public insurance companies in the Netherlands. The Dutch multi-disciplinary guideline on 'Dyspepsia management' recommends PPI therapy for typical reflux symptoms for a maximum of eight weeks [6]. Only severe oesophagitis grade C/D requires long-term treatment with PPI. In most other cases gradual termination is possible.

However, many physicians repeat prescriptions without systematic evaluation of symptoms. Consequently Dutch national prevalence data of oesophagitis do not match with the rate of people using ASD, indicating that prescription recommendations are not adequately implemented [7–9].

Many patients with recurrent dyspeptic or reflux complaints also believe they have to use ASD lifelong [9–13]. Rebound effects and not explicit placebo-effects are additional factors for patients' pressure for medication. This calls for GP assisting interventions, aiming at cessation of chronic ASD use [14–16]. While ASD users consume an increasing part of the pharmaceutical budget, more effective use of resources of health care is necessary [17, 18]. Better affordable strategies to reduce ASD are required to stimulate a rational pharmacotherapy.

Traditional strategies of implementation of guidelines, like passive education or economic measurements to optimise particular prescribing management have proven to be ineffective [19–21]. Grol et al demonstrated that GPs need several attributes to comply with recommendations in guidelines [22–24]. Suggesting that interventions based on multiple strategies will be more successful when actively implemented. Earlier reviews of dyspepsia guidelines enclosed only studies with single intervention strategies of various backgrounds. Recent reviews also evaluated combined strategies like audit, feedback or outreach visits, but the information provided did not permit conclusions pertaining the effect on prescription management only [25–28]. In this review we systematically evaluate the effectiveness of intervention methods for implementation of dyspepsia guidelines with the objective to reduce the volume and costs of ASD prescriptions.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search from 1995 to 2004 in Medline, Embase and the Cochrane Library which included search parameters of the following subject heading terms: 'dyspepsia', 'guideline', 'medication', 'implementation' and 'costs effectiveness'. Furthermore reference sections in original papers and reviews were screened to find studies otherwise published.

Selection of studies was done in two stages. In the first stage studies were screened by titles and abstracts for the description of involvement in an intervention aimed at changing management of dyspepsia. In the second stage the full text of the selected articles was retrieved to proceed the final selection by two criteria. The first inclusion criterion was that studies met criteria for adequate methodology and design. RCT and cohort follow up studies demonstrating quality criteria of evidence (A, B) set by Jailwala et al, were considered eligible to be included in the review [29]. The second inclusion criterion was the presence of outcome measurements related to reduction of medication: proportion of patients that stopped; the number of prescriptions or mean dosage of ASD; effectiveness of diagnostic tests on prescriptions; prescription costs or total disease related costs. Finally we classified the differences in strategy by which guidelines were implemented in daily clinical care: passive hand-over of (education) materials (I), or active strategies by a single (II) or multiple (III) interaction with patients and/or practitioners.

The criteria selection for design and outcome assessment in the second stage was performed independently by a second reviewer (NdeW) and disagreement was resolved by consensus. Non-systematic studies that did not evaluate the intervention or did not report outcome measurements were excluded. After a description of the type of intervention of the included studies, from each study the data pertaining to the effectiveness of the intervention were extracted. Outcome figures of prescriptions volume and costs, as well as the expenditures per patient were analysed to compare the differences in effects related to the intervention method.

Results

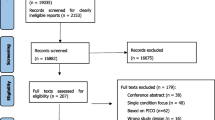

We found 37 articles that met the inclusion criteria, 26 in the search selection and 8 in the reference sections of studies. Of these articles, 16 were marked as review articles and 21 represented original research reports (Figure 1).

Seven of the original studies were excluded because they described guidelines or measured the compliance to guidelines without reporting relevant outcomes [30–36]. Another three studies were excluded because they were limited to policy evaluations and one study was excluded because it described a theoretical model [37–40].

Finally, 10 studies were eligible to be included in analysis (Table 1) [41–50]. Seven of these studies were designed as RCT (A2) [43–48, 50]. The inclusion of the research population and baseline similarity for the intervention was well described and five of them included intention to treat analysis, but most studies had shortcomings in reporting outcomes and statistics.

In the cohort studies (B) the number of involved GPs was unknown and outcomes were not reported sequentially and in the multi-centre study (B) was the randomisation procedure unclear [41, 42, 49]. None of the B qualified studies described physicians' involvement in therapy management and one of them was a direct intervention from the government [41].

Three of the 10 selected studies did not evaluate cost-effectiveness. One study focused merely on costs. Excluding the evaluation of governments' intervention on population level (unknown numbers of GPs and patients), the studies involved a total of 847 GPs and/or 3512 patients.

Intervention methods

Intervention methods used in these studies were classified according to three pre-defined strategies. The first category focused on passive intervention without further implementation activities on individual patient or doctors level and enclosed the two cohort studies(I). The first evaluated the follow up of governmental directives [41]. The second followed up the revised GP therapy after discontinuing hospital treatment [49].

The RCTs were included in the two categories of active single (II) and active multiple (III) interventions. In the first category two studies reported effects of guidelines introduced to the physicians by education and consensus meetings and one study reported effects of a guideline addressed to patients to reduce themselves medication [47, 48, 50]. In the multiple active category most RCTs reported about GPs who were educated about guidelines together with active support, feedback or peer visitations during the intervention [42–46].

The selection process of practitioners and adherence to the intervention were not clearly reported in all RCT studies. The duration of the intervention period as well as the compliance in the groups was not always described systematically. In general RCTs, reported detailed about the intervention strategy.

Effect on the number of Prescription and Diagnostic tests

The study on the authorisation program of de government caused a decrease of 80% of all PPI prescriptions [41]. The study in which was addressed to patients to reduce their medication use, ASD prescriptions decreased by 17% [50]. In the remaining eight GP centred intervention studies, half of them introduced and promoted H. pylori tests, while the other half focused on guideline education with feedback strategies, the effects demonstrated variable outcomes. In the H. pylori tests group GPs were reinstructed for treatment, or were activated for using more H. pylori tests, which resulted in two unknown numbers of less ASD users and in one number of 31% patients that ceased ASD use [49, 46, 42]. The use of more tests caused in one study more endoscopic referrals. The forth study of this group invited patient for a H. pylori test, which resulted in 8% less ASD users.

In the guideline and feedback group GPs held consensus meetings or were given feedback about their prescription policies, but in three of these studies effects on ASD use were not reported [47, 43, 45]. In the fourth study of this group GPs got a prescription protocol and were extensively visited, what resulted in 40% less ASD users [44].

In general reduction of ASD was not described systematically, but if so studies with multiple active interventions demonstrated better results.

Costs effects

From the cohort studies (I) the authorisation program in Canada reported 62% sustained decrease of costs for PPI [41]. The other cohort study and the one with serological H. pylori tests demonstrated no significant cost effects or did not report calculations [42, 49].

In the studies with single intervention method (II) the promotion of the dyspepsia protocol resulted in an increase of 22% ASD costs [47]. The other two studies demonstrated by involving patients successful reduction of ASD, but costs effect calculations were not presented [48, 50]. From the multiple intervention methods (III) three studies demonstrated costs effects varying respectively of 6% increase of ASD costs, no significant changes of overall medication costs until to 5% decrease in medication costs [46, 45, 43].

Calculation of costs in all studies was not done systematically nor uniform. Sometimes percentages of ASD costs were given, sometimes the absolute costs and sometimes none of the two. Some studies reported overall medical costs, including ASD costs. The different costs calculations are therefore difficult to compare in this review.

Discussion

There is no doubt that radical changes can be reached from a governments' intervention, but when doctors receive a passive mailing or recommendations of key players to pay more attention to prescription protocols the effects on the number of prescriptions and costs are disappointing [21]. Studies with more active intervention strategies that support the doctors with recommendations and visitations had better results.

In studies as identified for this review many of the interventions were concerned with eradication of H. pylori, which resulted in small changes of the number of ASD users or prescriptions. Focussing on positive effects of ASD reduction and related costs two of the three single intervention studies (II) demonstrated positive results. Among the four multiple intervention studies (III) three reported a positive cost reducing effect. On average this implies only a modest effect, comparable to the small effects observed in the earlier Cochrane reviews on the effects of changes in professional behaviour [26–28].

There was only one study that particularly intervened on the gradual termination of unnecessary use of ASD [14]. The GPs were recommended to accompany their patients which resulted in a larger decrease of ASD volumes. However costs were not calculated.

The overall conclusion is that the number of high-quality studies on effective interventions for ASD reduction is limited. In addition the incomparable methods applied to calculate prescription rates and costs preclude identification of the most effective intervention strategies. The latter can only be achieved after several studies, including similar outcome measurements evaluating distinct well-defined interventions, have become available.

Only a few quantitative studies evaluated with varying success that ASD reduction requires active intervention strategies with practical instrument for the GP. Grol and Grimshaw already showed the performance phenomenon that actual changes in practice depend on helpful attributes and in particular on attributes that will overcome identified barriers against changing behaviour [17, 18]. More RCT studies on population level have to calculate more thoroughly the effects that appoint to the particular successful instruments.

Doctors need rational arguments to get cooperation from patients. As long as side-effects of long term use of ASD are unknown and rebound effects make patients afraid to stop, to negotiate with patients to reduce medication is not an attractive alternative [12, 24].

From this point of view government's interventions like in Canada, which forces cooperation of patients and doctors by financial incentives, seems attractive, but sustainability is questionable [38]. An alternative could be that insurance companies introduce financial rewards, either for the doctor or the patient, to defeat barriers and enforce their negotiations. They possible too could facilitate to combine interventions, both practical instruments and financial compensation, into an effective intervention program of ASD reduction. Evaluation of these multi-interventions have to demonstrate which combinations of instruments fits GPs best.

Conclusion

Studies demonstrate that evidence for effective interventions is limited and cost-effectiveness is often difficult to compare. Larger multi-intervention studies with similar outcome measurements and distinct interventions are needed to evaluate the most successful instruments.

References

Agis Zorgverzekeringen: Chronic acid-suppressive drug use in Amsterdam in 2002. Amersfoort, Agis. 2003

Stichting Farmaceutische Kengetallen: Farmacie in Cijfers: maagmiddelen. Pharmaceutisch Weekblad. 2000, 135: 27.

Okkes IM, Oskam SK, Lamberts H: Van klacht naar diagnose. Episodegegevens uit de huisartspraktijk. 1998, Bussem, Coutinho

GIP Signaal: Gebruik van maagmiddelen 1996–2001. Genees- en hulpmiddelen Informatie Project/College voor Zorgverzekeringen, Amstelveen. 2002, nr.2

Quartero AO, Smeets HM, Wit de NJ: Trends and determinants of Pharmacotherapy for dyspepsia: analysis of 3-year prescription data in the Netherlands. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003, 38: 676-677. 10.1080/00365520310001923.

Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de Gezondheidszorg CBO: Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Maagklachten. Alphen aan de Rijn, Van Zuiden Communications. 2003

Van Der Linden MW, Westert GP, De Bakker DH, Schellevis FG: Tweede nationale studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk. Klachten en aandoeningen in de bevolking en in de huisartspraktijk. 2004, Utrecht, Nivel

Delaney BC: Review article: prevalence and epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004, 20 (Suppl 8): 2-4. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02219.x.

Fraser A, Delaney B, Moayyedi P: Symptom-based outcome measures for dyspepsia and GERD trials: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005, 100 (2): 442-52. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40122.x.

Soo S, Moayyedi P, Deeks J, Delaney B, Innes M, Forman D: Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia (Cochrane review). The Cochrane Library. 2000, Oxford:Updata, 2

Quartero AO, Post WMW, Numans ME, De Melker RA, De Wit NJ: What makes the dyspeptic patient feel ill? A cross sectional survey of functional health status, Helicobacter pylori infection, and psychological distress in dyspeptic patients in general practice. Gut. 1999, 45: 15-19.

Talley NJ, Lauritsen K, Tunturi-Hihnala H, Lind T, Moum B, Bang C, Schulz T, Omland TM, Delle M, Junghard O: Esomeprazole 20 mg maintains symptom control in endoscopy-negative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a controlled trial of 'on demand' therapy for 6 months. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001, 15: 347-54. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00943.x.

Delaney B, Ford AC, Forman D, Moayyedi P, Qume M: Initial management strategies for dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005, CD001961-, 4

Hurenkamp GJ, Grundmeijer HG, Van Der Ende A, Tytgat GN, Assendelft WJ, Van Der Hulst RW: Arrest of chronic acis suppressant drug use after successful H. Pylori eradication in patients with peptic ulcer disease: a six-month follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001, 15 (7): 1047-54. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01017.x.

Talley NJ: Drug treatment of functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991, 182 (): 47-60.

Hurenkamp GJB, Grundmeyer HGLM, Bindels PJE, Tytgat GNJ, Van Der Hulst RWM: How do primary care physicians use long-term Acid suppressant drugs? A population-based analysis of Dutch general practices. J Fam Pract. 2002, 51: 241-45.

College voor Zorgverzekeringen: Rapport Twee markten verkent. Experimentele ontmanteling GVS en loslating WTG-vergoedingssystematiek: maagmiddelen en cholesterolverlagers. 2002, Amstelveen, CVZ

Wilhelmsen I: Quality of life in upper gastrointestinal disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1995, 211: 21-25. 10.3109/00365529509090288.

O'Connor HJ: Helicobacter pylori and dyspepsia: physicians' attitudes, clinical practice, and prescribing habits. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002, 16 (3): 487-96. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01183.x.

Talley NJ, Vakil N, Delaney B, Marshall B, Bytzer P, Engstrand L, de Boer W, Jones R, Malfertheiner P, Agreus L: Management issues in dyspepsia: current consensus and controversies. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004, 39 (10): 913-8. 10.1080/00365520410003452.

Cardin Fabrizio, Zorzi Manuel, Bovo Emanuela, Guerra Cosimo, Bandini Fabio, Polito Daniele, Bano Francesca, Grion Anna Maria, Toffanin Roberto: Effect of implementation of a dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori eradication guideline in primary care. Digestion. 2005, 72 (1): 1-7. 10.1159/000087215. Epub 2005 Jul 25

Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA: Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. BMJ. 1998, 317: 465-468.

Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L: Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001, 39 (8 Suppl 2): II2-45.

Grol R, Dalhuijsen J, Thomas S, In't Veld C, Rutten G, Mokking H: Attributes of clinical guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: observational study. BMJ. 1998, 317: 858-61.

Jones RH, Lydeard S, Dunleavey J: Problems with implementing guidelines: a randomised controlled trial of consensus management of dyspepsia. Quality in Health Care. 1993, 2: 217-21.

Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O'Brien MA, Oxman AD: Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, CD000259-2

O'brien M, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman A, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen D, Forsetlund L, Bainbridge D, Freemantle N, Davis DA, Haynes R, Harvey E: Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, CD000409-4

Shaw B, Cheater F, Baker R, Gillies C, Hearnshaw H, Flottorp S, Robertson N: Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005, CD005470-3

Jailwala J, Imperial TF, Kroenke K: Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 133 (2): 136-47. 2000 Jul 18

Axon AT, Bell GD, Jones RH, Quine MA, McCloy RF: Guidelines on appropriate indications for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Working Party of the Joint Committee of the Royal College of Physicians of London, Royal College of Surgeons of England, Royal College of Anaesthetists, Association of Surgeons, the British Society of Gastroenterology, and the thoracic Society of Great Britain. BMJ. 310 (6983): 853-6. 1995 Apr 1

Hungin AP, Rubin GP, Russell AJ, Convery B: Guidelines for dyspepsia management in general practice using focus groups. Br J Gen Pract. 1997, 47 (418): 275-9.

Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJO, Flook N, Chiba N, Armstrong D, Barkun A, Bradette M, the Canadian Dyspepsia Working Group, et al: An evidence-based approach to the management of uninvestigated dyspepsia in the era of Helicobacter pylori. CMAJ. 162 (12 Suppl): s3-23. 2000 June 13

Walter LP, Fendrick M, Cve DR, Peura DA, Garabedian-Ruffalo SM, Laine L: Helicobacter pylori-related disease. Guidelines for Testing and Treatment. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160: 1285-91. 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1285.

Mamdani MM, Tu K, Jaakkimainen L, Bica A, Hux J: Proton pump inhibitors. Compliance with a mandated step-up program. Can Fam Physician. 2001, 47: 531-5.

Manes G, Balzano A, Marone P, Lionello M, Mosca S: Appropriateness and diagnostic yield of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in an open-access endoscopy system: a prospective observational study based on the Maastricht guidelines. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002, 16 (1): 105-10. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01136.x.

Cardin F, Zorzi M, Furlanetto A, Guerra C, Bandini F, Polito D, Bano F, Grion AM, Toffani R: Are dyspepsia management guidelines coherent with primary care practice?. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002, 37 (11): 1269-75. 10.1080/003655202761020533.

De Wit NJ, Mendive J, Seifert B, Cardin F, Rubin G: Guidelines on the management of H. pylori in primary care: development of an implementation strategy. Fam Pract. 2000, 17 (Suppl 2): s27-32. 10.1093/fampra/17.suppl_2.S27.

Chey WD, Fendrick AM: Noninvasive Helicobacter pylori testing for the 'test-and-treat' strategy: a decision analysis to access the effect of past infection on the test choice. Arch Intern Med. 161 (17): 2129-32. 10.1001/archinte.161.17.2129. 2001 Sep 24

No authors: Treating dyspepsia: new OTC drug changes the economic picture. Dis Manag Advis. 2003, 9 (10): 133-4.

Sanchez-del Rio A, Quintero E, Alarcon O: Appropriateness of indications for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in open-access endoscopy units. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004, 27 (3): 119-24. 10.1157/13058395.

Bursey F, Crowley M, Janes C, Turner CJ: Cost analysis of a provincial drug program to guide the treatment of upper gastrointestinal disorders. CMAJ. 162 (6): 817-23. 2000 Mar 21

Ladabaum U, Fendrick AM, Scheiman JM: Outcomes of initial non-invasive Helicobacter pylori testing in U.S. primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001, 96 (7): 2051-7. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03938.x.

Chan D, Patel P, Booth L, Lee D, Dent ThHS, Harris F, Sadler M, Shepherd H: A novel approach for implementing evidence-based guidelines in the community: the Appropriate Choices in Dyspepsia project. Journal of Clinical Excellence. 2001, 2: 219-23.

Hurenkamp GJ, Grundmeijer HG, Van Der Ende A, Tytgat GN, Assendelft WJ, Van Der Hulst RW: Tapering the use of chronic acid suppressant drugs in H. pylori negative chronic dyspeptic patients on maintenance therapy; an intervention strategy. Thesis, Amsterdam. 2001

Weijnen CF, De Wit NJ, Wensing M, Numans ME, Verheij TJM, Hoes AW: Financial incentive versus education for implementation of a dyspepsia guideline: a randomised trial in primary care. Gastroenterol. 2002, 122 (Suppl 1A): 576-9.

Banait G, Sibbald B, Thompson D, Summerton C, Hann M, Talbot S: Salford and Trafford Ulcer Research Network. Modifying dyspepsia management in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial of educational outreach compared with passive guideline dissemination. Br J Gen Pract. 2003, 53 (487): 94-100.

Jones RH, Lydeard S, Dunleavey J: Problems with implementing guidelines: a randomised controlled trial of consensus management of dyspepsia. Quality in Health Care. 1993, 2: 217-21.

Allison JE, Hurley LB, Hiatt RA, Levin ThR, Ackerson LM, Lieu TA: A randomized controlled trial of Test-and-Treat strategy for Helicobacter pylori. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163: 1165-71. 10.1001/archinte.163.10.1165.

Kearney DJ, Liu CF, Crump C, Brousal A: The effect of Helicobacter pylori treatment strategy on health care in patients with peptic ulcer disease and dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003, 98: 1952-62. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07584.x.

Krol N, Wensing M, Haaijer-Ruskamp F, Muris JWM, Numans ME, Schattenberg G, van Balen J, Grol R: Patient-directed strategy to reduce prescribing for patients with dyspepsia in general practice: a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 19 (8): 917-22. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01928.x. 2004 Apr 15

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/7/177/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank Paul van Dijk from Agis Health Insurance Company, who planned the acid suppressing drug program in which space was given for the performance of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HMS conceived of the study, conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. NJdeW participated in the design and analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. AWH helped to draft the manuscript and approved the final concept. They all approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Smeets, H.M., Hoes, A.W. & de Wit, N.J. Effectiveness and costs of implementation strategies to reduce acid suppressive drug prescriptions: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 7, 177 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-177

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-177