Abstract

Background

Obesity in Canada is a growing concern, but little is known about the available services for managing obesity in adults. Our objectives were to (a) survey and describe programs dedicated to weight management and (b) evaluate program adherence to established recommendations for care.

Methods

We conducted an online environmental scan in 2011 to identify adult weight management services throughout Canada. We examined the degree to which programs adhered to the 2006 Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management and Prevention of Obesity in Adults and Children (CCPGO) and the analysis criteria developed by the Association pour la Santé Publique du Québec (ASPQ).

Results

A total of 83 non-surgical (34 community-based, 42 primary care-based, 7 hospital-based) and 33 surgical programs were identified. All programs encouraged patient self-management. However, few non-surgical programs adhered to the CCPGO recommendations for assessment and intervention, and there was a general lack of screening for eating disorders, depression and other psychiatric diseases across all programs. Concordance with the ASPQ criteria was best among primary care-based programs, but less common in other settings with deficits most frequently revealed in multidisciplinary health assessment/management and physical activity counselling.

Conclusions

With more than 60% of Canadians overweight or obese, our findings highlight that availability of weight management services is far outstripped by need. Our observation that evidence-based recommendations are applied inconsistently across the country validates the need for knowledge translation of effective health services for managing obesity in adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The high prevalence of obesity in adults [1] and its serious health consequences [2–4] pose a major challenge for the Canadian health care system. The direct costs of overweight and obesity in Canada equaled six billion Canadian dollars in 2006, representing 4.1% of total health care expenditures [5]. In response, a national strategy on healthy living and prevention of chronic diseases was developed [6]. In parallel, many provinces have devoted resources to addressing obesity, mainly by increasing the availability of bariatric surgery [7–9]. To help guide obesity care, the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management and Prevention of Obesity (CCPGO) emphasize the fundamental role of multidisciplinary health care teams to effectively manage obesity [10].

Despite increased awareness of obesity, little is known about weight management services available to Canadian adults. Almost three-quarters of overweight and obese Canadian adults have tried to lose weight, but very few have reported receiving advice about weight management from health care providers [11]. This suggests that the health care system is not providing weight management services, which results in m any Canadians accessing the unregulated commercial weight-loss industry. The availability of commercial services varies substantially in quality, safety, and effectiveness, leading the Association pour la santé publique du Québec (ASPQ) to publish a reference guide outlining the fundamental principles that individuals can use to inform decision-making regarding weight management services [12]. Independently, a recent workshop of stakeholders from across Canada identified the completion of an inventory of health services for managing obesity as an important step to identify research priorities, policy directives, and resource allocation within the health care system [13]. With reference to this foundational work, the aims of this study were to (a) complete the first pan-Canadian environmental scan to identify programs for managing obesity in adults and (b) evaluate the degree to which programs adhere to recommendations from the CCPGO and ASPQ.

Methods

Study design

An online survey was created in collaboration with and hosted by the Canadian Obesity Network-Réseaucanadien en obésité (CON-RCO, (http://con-initiatives.com/adultscan), which was based on previous research to quantify the number of pediatric weight management programs in Canada [14]. Our team used several strategies to ensure the survey was widely promoted at national level. For instance, all CON-RCO members (n >6500 as of 2011) received two email invitations in February and July 2011. Dr. Arya Sharma (CON-RCO Scientific Director) posted survey details on his blog in March 2011. The survey was advertised extensively during the 2nd National Obesity Summit, which was attended by over 800 obesity clinicians and researchers in Montreal, Quebec (May 2011). Invitations were distributed through 15 Canadian health care professional organizations (see acknowledgements) in early 2011. Finally, all individuals who completed the survey were encouraged to forward it to their colleagues to encourage recruitment through ‘word-of-mouth’.

All the program organizations were contacted by telephone or email between August and December 2011 to validate the information. For the sake of inclusivity, the definition of ‘weight management program’ was left to the discretion of program representatives. To calculate the number of programs per million of overweight or obese individuals, we divided the number of programs in each province by the number of persons who reported a body mass index (BMI) that classified them as overweight or obese in the CANSIM database (Statistics Canada, CANSIM, table 051-0001. Last modified: 2011-09-28).

Program classification and rating

Non-surgical, publically funded programs as well as private, for-profit programs were categorized according to their setting. Three types of programs were classified: 1) a service offered in the community, e.g., group-based education and exercise sessions, was categorized as a ‘community-based program’, 2) a program that included individual assessment and counselling by a health care professional, e.g., physician and dietician, in the primary care environment was considered a ‘primary health care program’, and 3) a program based in a hospital was considered a ‘hospital-based program’. Any program that (i) had either a psychiatrist, a psychologist or a social worker on the health care team and (ii) reported offering psychological/emotional support services, e.g., stress management and emotional eating, or behavioral therapy was categorized as offering ‘psychological/behavioral counselling’. Commercial programs were invited to participate in the survey. They were classified in community-based or primary care programs depending on the presence of a physician in the team.

Programs were scored for their concordance with the CCPGO assessment recommendations according to the seven indicators presented in Table 1 [10]. We also assessed the programs according to four of the seven ASPQ reference guide’s criteria that we were able to evaluate within the survey (Table 1) [12]. For example, a program promoting a credible rate of weight loss, e.g., less than 1 kilogram per week, or a credible weight management objective, e.g., 5 to 10% weight loss over six months, was considered adherent to the first criterion. The second criterion included two elements (the approach and the supervision). The ‘approach’ criterion was met for lifestyle modification or if food supplements or meal replacements were prescribed by a health professional. The ‘supervision’ criterion was met if the program was delivered by at least two health care professionals from different disciplines, e.g., physician and dietitian. A program offering nutritional counselling without the use of a long-term, very low energy diet, e.g., less than 1000 calories per day, adhered to the third criterion. Finally, a program offering physical activity counselling adhered to the fourth criterion.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and StatXact 3.1 (CytelInc, Cambridge, MA). Because all continuous variables were non-normally distributed, results are reported as median ± interquartile ranges (IQR, 25th–75th percentiles). Categorical variables are reported as proportions. Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used to examine differences between types of programs. A Bonferroni correction was used for multiple testing. We considered differences to be significant if the p-value was <0.05. The reported sample sizes (n) correspond to the number of programs for which information was available.

Results

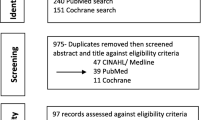

The online survey received 117 program entries from February to December 2011. In addition, our team manually entered data from nine surgical programs that did not complete the online survey, but were referred to us by the Canadian Association of General Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Working Group. Out of a total of 126 programs, ten were excluded (two were non-Canadian, three had duplicate entries, two non-surgical programs registered without completing the survey and could not be contacted for data verification, one was dedicated to animals, one included individuals exclusively with diabetes, and one program was discontinued before we were able to validate their information). The geographical distribution of the 116 remaining programs is shown in Table 2. The number of programs per million overweight or obese individuals in each province is shown in Figure 1, while the number of programs in relation to the total population of each province is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Program characteristics

Most programs were delivered at a single site (min = 1 site, max = 1502 sites; IQR 1–1 site, n = 112). The median time since the establishment of the program was five years (IQR 2–9.25 years, n = 107). Other program characteristics, e.g., source of funding and participation in research, are described in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Program inclusion criteria

Programs had a variety of referral processes, including physician only (16%, n = 107), physician and/or other health care professional (16%, n = 107), and self-referrals (68%, n = 107). Only 33% (n = 24) of surgical programs accepted self-referrals; however, self-referral was very common among community-based programs (91%, n = 34). The median minimum patient age for referral was 18 years old (IQR 16–18 years old, n = 109) whereas the median patient maximal age for referral was 70 years old (IQR 65–80years old, n = 82), although approximately one-quarter (24%, n = 108) did not apply an upper age limit. Most programs used BMI as the primary inclusion criterion (Table 3) and applied exclusion criteria [surgical programs (100%, n = 27), community-based programs (71%, n = 34), primary health care programs (59%, n = 41) and hospital-based programs (86%, n = 7)], the most common being the presence of an active uncontrolled psychiatric disorder ,e.g., substance abuse, mental disease and eating disorder.

Patient assessment

Table 4 presents the assessment of patients according to the CCPGO recommendations. In general, community-based programs included the evaluation of fewer items than other categories of programs. Waist circumference (WC) was not measured systematically across all programs and screening for eating disorders, depression, and/or other psychiatric diseases was infrequently completed. Surgical programs tended to satisfy more of the recommendations (median score: 5/7) than non-surgical programs (median score: 3/7).

Types of intervention

Figure 2 describes the types of intervention offered. Bariatric surgery procedures performed by surgical programs (n = 29) included adjustable gastric banding (72%), sleeve gastrectomy (66%), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (59%), biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (10%), and intragastric balloon (7%). Most surgical programs (72%, n = 29) offered more than one type of procedure. Surgical programs offered less physical activity counselling than non-surgical programs (Table 5). Consistent with the CCPGO [10], support for self-management was provided by most programs [surgical programs (83%, n = 24), community-based programs (88%, n = 34), primary health care programs (98%, n = 42), and hospital-based programs (100%, n = 7)].

Types of intervention offered by the different categories of programs. Surgical programs n = 33 (for intervention components other than bariatric surgery n = 25 and for psychological/behavioral component n = 24), Community-based programs n = 34, Primary health care programs n = 42 and Hospital-based programs n = 7. Bariatric surgery = *, †, ‡. Pharmacotherapy for the management of weight = §. Nutritional counselling = none. Physical activity counselling = †. Psychological/behavioral component = none. *Significant difference between surgical programs and community-based programs. † Significant difference between surgical programs and primary health care programs. ‡ Significant difference between surgical programs and hospital-based programs. § Significant difference between community-based programs and primary health care programs.

Analysis according to selected ASPQ criteria

Few programs adhered to the four ASPQ criteria that we evaluated, but primary care programs rated the highest degree of adherence (Table 5). The main deficiencies included a lack of a multidisciplinary health care team and absence of physical activity counselling. Figure 3 shows the degree of program multidisciplinarity and Table 6 describes the types of health care professionals included on the teams. Surgical programs had a greater variety of team members and total number of health care professionals versus non-surgical programs. Community-based programs tended to include services that were provided by health care professionals working individually.

Different types of professionals involved in weight management programs. Surgical programs n = 24, Community-based programs n = 34, Primary health care programs n = 42 and Hospital-based programs n = 7. *, †, ‡. *Significant difference between surgical programs and community-based programs. † Significant difference between surgical programs and primary health care programs. ‡ Significant difference between surgical programs and hospital-based programs.

Discussion

Our nationwide survey is the first comprehensive assessment of health services for managing obesity in Canadian adults. Overall, our research revealed several important findings. First, weight management programs in Canada are scarce, with approximately nine programs per million overweight or obese people. Second, the evaluation of the programs’ initial assessment and intervention according to CCPGO recommendations showed that (a) only primary health care programs systematically measure WC, (b) community-based programs tend to not complete physical examination and assessment of comorbidities compared with other types of programs, and (c) there is a lack of screening for mental health issues across all program categories. Third, most programs support their patients towards self-management. Finally, most programs did not fulfill the ASPQ criteria, with multidisciplinary assessment/management and physical activity counselling being the most deficient. However, primary care programs have the best concordance scores with the ASPQ criteria.

Few national reports have been published regarding health services available for managing obesity. For instance, one US-based report surveyed obesity treatment programs for both adults and children in public hospitals, which makes it difficult to directly compare with our study [15]. Nevertheless, the authors showed that the most frequent types of interventions for adults were nutrition-based (37.5%), clinic-based (35.0%), bariatric surgery (28%), primary care-based (20%), and research-based (17.5%). These findings are consistent with our observations. Compared with the recent survey of pediatric weight management programs in Canada [14], we found both a greater number and variety of services. This observation is most likely explained by the diversity of management settings available to the adult population compared with the pediatric population, which included mostly hospital-based services [14]. There were few hospital-based, non-surgical programs in our survey, suggesting that few hospitals are actively providing weight management outside of bariatric surgery. There is a need to develop this resource in the future to manage more complex cases, especially when surgery is not available or contraindicated.

Our results also show that although most programs (except community-based programs) measured patients’ BMI, only primary care programs systematically measured WC. For surgical programs, this might be explained by the fact that patients with severe obesity usually have a very high WC, and the measurement tends to be unreliable [16]. However, there is a need to focus on the WC measurement for adults, especially those with a BMI <35 kg/m2, which is consistent with the CCPGO recommendations [10]. In addition, there was a lack of screening of eating disorders, depression, and other psychiatric diseases in all categories of programs, including the surgical programs. This is surprising since patients with severe obesity have a high prevalence of depression [17, 18], anxiety disorders [18] and eating disorders [19]. In addition, it is important to objectively assess the psychological health of individuals seeking bariatric surgery [20–22]. Nonetheless, a report by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death in the United Kingdom highlighted that only 29% of bariatric surgery patients had received any psychological input into their care, suggesting that even if bariatric surgery programs offer a psychological/behavioral component, few patients complete an assessment or receive care [23]. Our results are also in line with a recent Omnibus survey that indicated the current obesity guidelines are still not effectively implemented [11]. Although numerous interventions have been shown to be effective [24–26], guidelines are still applied inconsistently in routine care by health professionals because of barriers such as time constraints, lack of awareness or familiarity with the guidelines, disagreement with the guidelines’ conclusions or relevance, lack of resources and support, or lack of motivation to work with patients with obesity [27–29]. Finally, the majority of programs did not adhere to the criteria recommended by ASPQ [12]. However, primary care-based programs adhered most closely to these criteria, which is encouraging, since this is where most Canadians access the health care system. Furthermore, as others have shown [30], there was a lack of physical activity counselling in the surgical programs. This is surprising since it appears that exercise may help weight loss after the surgery [31–33] and that physical activity favors weight maintenance [34–36].

Some limitations must be taken into consideration when interpreting our data. First, despite using a variety of methods to ensure our survey was circulated broadly throughout Canada, some programs may not have been surveyed. Second, our results relied on self-reported data, although our efforts to validate the data using follow-up telephone interviews with program representatives minimized this bias. Third, programs that could not be reached by telephone for validation had some missing data. Nevertheless, the use of a standardized questionnaire allowed us to compare programs. It should also be noted that some criteria of concordance with CCPGO recommendations, e.g., assessing readiness to change and realistic weight loss goals, lack empirical validation. We chose to report ‘programs per million overweight or obese people’, but this metric does not capture the number of people served per million since a program may serve 13 or 40,000 patients a year. Finally, not all the ASPQ criteria were applied because of the lack of data, e.g. costs and advertising.

Conclusions

Although high-quality weight management services are offered in academic, public, and private practices in Canada, the supply of services is vastly outstripped by potential demand across the country. Few non-surgical programs follow the CCPGO recommendations for assessment, especially for screening of psychiatric or eating disorders. In addition, the majority of programs do not adhere to the ASPQ criteria, with multidisciplinary assessment/management and physical activity counselling being the most deficient. This national perspective can help to inform clinicians and administrators within the Canadian health care system to understand existing strengths, as well as address areas of weakness that require additional planning and implementation to optimize obesity-related health services for adults with obesity.

References

Canada S: Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2, Nutrition (2004). In. 2004, Health Canada: Ottawa

NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification Evaluation and Treatment of Obesity in Adults (US): Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults--the evidence report. National institutes of health. Obes Res. 1998, 6 (Suppl 2): 51S-209S.

WHO: Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. 2000, Geneva, Switzerland: WHO technical report series, 894

Kortt M, Baldry J: The association between musculoskeletal disorders and obesity. Aust Health Rev. 2002, 25 (6): 207-214. 10.1071/AH020207.

Anis AH, Zhang W, Bansback N, Guh DP, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL: Obesity and overweight in Canada: an updated cost-of-illness study. Obes Rev. 2009, 11 (1): 31-40.

Health Canada: The Government of Canada reaffirms its commitment to combat Canada's rising obesity levels. 2005, Ottawa: Health Canada

Alberta Health Services: Becoming the Best: Alberta’s 5-Year Health Action Plan 2010-2015. 2010, Edmonton: Governement of Alberta

Bariatric surgery: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2005, 5 (1): 1-148.

Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec: L'organisation de la chirurgie bariatrique au Québec: Plan d'action. La Direction des communications du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec edn. 2009, Québec: Gouvernement du Québec

Lau DC, Douketis JD, Morrison KM, Hramiak IM, Sharma AM, Ur E: 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. Cmaj. 2007, 176 (8): S1-13. 10.1503/cmaj.061409.

Kirk SF, Tytus R, Tsuyuki RT, Sharma AM: Weight management experiences of overweight and obese Canadian adults: findings from a national survey. Chronic Dis Inj Canada. 32 (2): 8.

Mongeau L, Vennes M, Sauriol V: Losing weight for better, not worse : guidebook on the principles of healthy weight management and on a critical analysis of weight-loss products and services. 2005, Montréal: Association pour la santé publique du Québec, 64.

CIHR: Developing a research agenda to support bariatric care in Canada workshop report. 2010, Montréal: CIHR Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes and The Canadian Obesity Network, 35.

Ball GD, Ambler KA, Chanoine JP: Pediatric weight management programs in Canada: where, what and How?. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011, Jun, 6 (2–2): e58-61.

Siegel S, Marshall L, Cummings L: Obesity treatment programs in public hospitals and health systems. 2008, Washington: National Association of Public Hospitals and Health Systems

Janssen I, Shields M, Craig CL, Tremblay MS: Prevalence and secular changes in abdominal obesity in Canadian adolescents and adults, 1981 to 2007-2009. Obes Rev. 2010, 12 (6): 397-405.

Xu Q, Anderson D, Lurie-Beck J: The relationship between abdominal obesity and depression in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2011, 5: e267-e278. 10.1016/j.orcp.2011.04.007.

Lykouras L: Psychological profile of obese patients. Dig Dis. 2008, 26 (1): 36-39. 10.1159/000109384.

Dahl JK, Eriksen L, Vedul-Kjelsås E, Strømmen M, Kulseng B, Mårvik R, Holen A: Depression, anxiety, and neuroticism in obese patients waiting for bariatric surgery: Differences between patients with and without eating disorders and subthreshold binge eating disorders. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2012, 6: e139-e147. 10.1016/j.orcp.2011.07.005.

LeMont D, Moorehead MK, Parish MS, Reto CS, Ritz SJ: Suggestions for the pre-surgical psychological assessement of bariatric surgery candidates. 2004, Gainesville, Florida: American Society for Bariatric Surgery

Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, Williams NN: Behavioral assessment and characteristics of patients seeking bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006, 14 (Suppl 2): 51S-52S.

Collazo-Clavell ML, Clark MM, McAlpine DE, Jensen MD: Assessment and preparation of patients for bariatric surgery. Mayo ClinProc. 2006, 81 (10 Suppl): S11-17.

National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD): Too Lean a Service? A review of the care of patients who underwent bariatric surgery. 2012, London: NCEPOD

Douketis JD, Feightner JW, Attia J, Feldman WF: Periodic health examination, 1999 update: 1. Detection, prevention and treatment of obesity. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Cmaj. 1999, 160 (4): 513-525.

NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: The prevention and treatment of obesity. Effective Health Care Bulletins. 1997, 3 (2): 1-12.

Kirk SF, Penney TL, McHugh TL, Sharma AM: Effective weight management practice: a review of the lifestyle intervention evidence. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012, 36 (2): 178-185. 10.1038/ijo.2011.80.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, Rubin HR: Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999, 282 (15): 1458-1465. 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458.

Puhl R, Brownell KD: Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001, 9 (12): 788-805. 10.1038/oby.2001.108.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA: The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009, 17 (5): 941-964. 10.1038/oby.2008.636.

Peacock JC, Zizzi SJ: An assessment of patient behavioral requirements pre- and post-surgery at accredited weight loss surgical centers. Obes Surg. 2011, 21 (12): 1950-1957. 10.1007/s11695-011-0366-5.

Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, Parikh JA, Dutson E, Mehran A, Ko CY, Gibbons MM: Exercise following bariatric surgery: systematic review. Obes Surg. 2010, 20 (5): 657-665. 10.1007/s11695-010-0096-0.

Egberts K, Brown WA, Brennan L, O'Brien PE: Does exercise improve weight loss after bariatric surgery? A systematic review. Obes Surg. 2012, 22 (2): 335-341. 10.1007/s11695-011-0544-5.

Jacobi D, Ciangura C, Couet C, Oppert JM: Physical activity and weight loss following bariatric surgery. Obes Rev. 2011, 12 (5): 366-377. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00731.x.

Schoeller DA, Shay K, Kushner RF: How much physical activity is needed to minimize weight gain in previously obese women?. Am J ClinNutr. 1997, 66 (3): 551-556.

Donnelly JE, Smith B, Jacobsen DJ, Kirk E, Dubose K, Hyder M, Bailey B, Washburn R: The role of exercise for weight loss and maintenance. Best Pract Res ClinGastroenterol. 2004, 18 (6): 1009-1029. 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.06.022.

Elfhag K, Rossner S: Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005, 6 (1): 67-85.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/69/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank: all representatives who submitted information regarding their weight management programs; Ximena Ramos Salas, Managing Director of the Canadian Obesity Network-Réseaucanadien en obésité (CON-RCO), and Brigitte Lachance, former Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec employee, who both participated in the design of the study; Nelson Loyola, the software consultant who developed the database and resolved technical problems; Dr. Arya Sharma, CON-RCO Scientific Director, who posted the information to access the survey on his blog; as well as all the associations who helped circulate information about the survey: the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, the College of Dietitians of British Columbia, the College of Dietitians of Manitoba, the College of Physicians & Surgeons of Alberta, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia, the Dietitians of Canada, the New Brunswick Association of Dietitians, the New Brunswick Medical Society, the Newfoundland and Labrador Kinesiology Association, the Nova Scotia Dietetic Association, the Nurses Association of New Brunswick, l’Ordreprofessionnel des diététistes du Québec, the Saskatchewan Dietitians Association, the Saskatchewan Medical Association and the Saskatchewan Registered Nurses’ Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there have no competing financial interests. The project was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, Partnerships for Health Systems Improvement, PHE-103970) and the Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec. The Centre de rechercheclinique Étienne-Le Bel is an FRQ-S funded research center. At the time of this research, Geoff Ball was a Population Health Investigator with Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions and a New Investigator of CIHR. Marie-France Langlois is the recipient of National researcher award from the Fonds de la recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQ-S).

Authors’ contributions

All of the authors contributed to the conception of the study. Marie-Michèle Rosa-Fortin performed all phone interviews, conducted the analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. Marie-France Langlois and Christine Brown also participated in data interpretation. All of the authors contributed to critically revise the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Electronic supplementary material

12913_2013_3007_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Figure S1: Number of programs per million of population in Canada in 2011* (* Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM, table 051-0001. Last modified: 2011-09-28.) (DOC 72 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosa Fortin, MM., Brown, C., Ball, G.D. et al. Weight management in Canada: an environmental scan of health services for adults with obesity. BMC Health Serv Res 14, 69 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-69

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-69