Abstract

Background

A significant minority of patients do not receive all the evidence-based care recommended for their conditions. Health care quality may be improved by reducing this observed variation. Composite measures offer a different patient-centred perspective on quality and are utilized in acute hospitals via the ‘care bundle’ concept as indicators of the reliability of specific (evidence-based) care delivery tasks and improved outcomes. A care bundle consists of a number of time-specific interventions that should be delivered to every patient every time. We aimed to apply the care bundle concept to selected QOF data to measure the quality of evidence-based care provision.

Methods

Care bundles and components were selected from QOF indicators according to defined criteria. Five clinical conditions were suitable for care bundles: Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease (CHD), Stroke & Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA), Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Diabetes Mellitus (DM). Each bundle has 3-8 components. A retrospective audit was undertaken in a convenience sample of nine general medical practices in the West of Scotland. Collected data included delivery (or not) of individual bundle components to all patients included on specific disease registers. Practice level and overall compliance with bundles and components were calculated in SPSS and expressed as a percentage.

Results

Nine practices (64.3%) with a combined patient population of 56,948 were able to provide data in the format requested. Overall compliance with developed QOF-based care bundles (composite measures) was as follows: CHD 64.0%, range 35.0-71.9%; Stroke/TIA 74.1%, range 51.6-82.8%; CKD 69.0%, range 64.0-81.4%; and COPD 82.0%, range 47.9-95.8%; and DM 58.4%, range 50.3-65.2%.

Conclusions

In this small study compliance with individual QOF-based care bundle components was high, but overall (‘all or nothing’) compliance was substantially lower. Care bundles may provide a more informed measure of care quality than existing methods. However, the acceptability, feasibility and potential impact on clinical outcomes are unknown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wide variation in the provision of evidence-based care is recognized as a fundamental issue in all health care systems worldwide. The consequences of such variation often impact negatively on patients in terms of health care quality, safety, experiences and increased financial costs (including additional treatments and litigation) associated with sub-optimal clinical practices [1, 2].

It is widely accepted that there is a need to minimize unnecessary variation to improve the reliability of best practice care provision and the associated financial costs [2–4]. Practicing evidence-based medicine and implementing clinical care guidelines are promoted to assist clinical decision making and optimal management of patients, but does not necessarily ensure that patients who should receive all appropriate care actually do so [5–8].

Around 50% of hospital patients may receive the full recommended care and treatments which their clinical condition merits. The difference between the highest and lowest performing health care systems suggests that there is ‘an enormous gap’ in evidence-based (or recommended) care provision [1, 9]. In primary care settings, evidence of wide variation has also been found between individual health care providers [10]. For example, in general medical practice in the United Kingdom (UK) substantial variation in patient care has been described in anxiolytic, hypnotic, antidepressant and antibiotic prescribing [11–13].

The Quality & Outcomes Framework (QOF) is a pay-for-performance (P4P) scheme that was introduced to UK general practice in April 2004 to help address longstanding variation in the quality of primary care provision [14]. Clinical conditions are suitable for QOF inclusion and therefore financial incentivisation if they are common, associated with significant morbidity (and to a lesser extent mortality), and are diagnostically unambiguous. Indicators should be evidence based, achievable by every primary care team, clearly defined and consistently extractable from different computerized information systems [14].

Since 2009, QOF indicators have been developed through a rigorous National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) led process which includes input from an expert panel and extensive piloting [14]. The Framework consists of a number of incentivized ‘point-in-time’ indicators arranged into four main groups: additional services, patient experience, organizational and clinical sections [15]. Practices ‘earn’ points according to their level of achievement for each indicator, with payment currently starting at a minimum threshold (usually 40%) rising to a maximum (usually 90%).

The average achievement of available QOF points for the period April 2009 to March 2010 was 93.7% in general practices in England and 97.2% in Scotland [16, 17]. The implication is that the quality of care delivered by practices to patients with incentivized disease conditions is very high. However, there is some concern that maximum payment thresholds for QOF indicators are actually too low and that the high performances achieved by most practices may give the inaccurate impression that care quality does not necessarily need to be improved further [18, 19].

There is growing interest in the use of composite – as well as individual - measures of care delivery as an alternative method of describing the quality of clinical care processes and outcomes [10]. The main benefit of the composite (‘all or nothing’) approach is that it may highlight opportunities for further improvement in care provision even when individual measures already indicate that care quality is high.

The care bundle concept is one such composite measure that is promoted as a systematic method of monitoring and improving the reliability and quality of health care [20–22]. A care bundle is simply a number of health care interventions grouped together and which normally have a synergistic relationship that impacts on clinical outcome [23]. Bundles usually contain three to six components which may include clinical interventions such as care processes, procedures, or diagnostic tests, but are not deemed suitable to act as comprehensive lists of all possible care. Selection of appropriate bundle components is based on best evidence, local considerations and may change with time and experiences [24, 25].

Specific care bundles have been implemented in a range of secondary care settings such as paediatric and adult ICU, medical and surgical wards and Accident and Emergency departments in North America and the UK [26, 27]. Related clinical outcomes have included significant reductions in health care acquired infections, condition-specific and all-cause mortality, and reduced re-admission rates of elderly patients, length of ICU stay and number of ventilation days [20, 28–30]. Although higher compliance rates with bundles are associated with improved outcomes [31], these are difficult to sustain because of a combination of system and human factors which often results in rates below 50% [32–34].

Measuring compliance with bundled interventions on a composite ‘all-or-nothing’ basis may provide the healthcare team with a more accurate indicator of care quality and evidence-based care provision [35]. In essence this means every relevant care component should routinely be delivered (or considered) for every single patient on time and every time. Embracing this rationale may act as a greater prompt to improve patient care than the current method of monitoring data with individual bundle elements, which can give a misleading impression of overall performance.

Evidence of the potential value of composite measures of care quality in general practice – specifically QOF data - is limited [36, 37]. Given the benefits of the bundle approach in acute hospital settings, we aimed to develop care bundles based on those QOF disease areas and indicators in general practice that were judged to be most suitable. We further aimed to measure individual and composite compliance with developed care bundles to highlight the extent of any potential care ‘gaps’ which may point to opportunities for further improvement.

Methods

Design of care bundles as proxies for composite measures

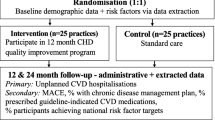

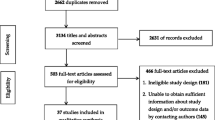

The condition-specific care bundles and associated individual components were selected from the ‘Quality and outcomes framework guidance for GMS contract 2009/10’ by the authors [15]. Studying QOF data was a pragmatic choice, as it provided a measure of current evidence-based clinical practices. We agreed selection criteria to help identify potentially suitable clinical conditions and indicators according to previous published guidance [24] and local practical considerations. All QOF sections and indicators were initially considered. The selection criteria (Table 1) were applied in a step-wise manner as illustrated in Figure 1 to exclude unsuitable indicators and conditions.

Measuring care bundle compliance

Setting and sample size

We emailed a convenience sample of 14 West of Scotland general practitioners (GPs) who are also senior medical educators based in the west region of NHS Education for Scotland (NES) with details of the proposed study during February 2011. We invited them to discuss the invitation with their practice teams and indicate to us a preparedness to participate.

Data collection

On the 31st March 2011 the practice manager in each participating practice identified and downloaded the relevant QOF data requested (using guidance provided) from local information systems to an encrypted USB mobile data device. This device was then transported by the GP educator to the regional office for analysis by the research team. The 31st March is the date on which recorded performance by the practice is formally measured against QOF criteria and associated annual earnings calculated. Practice teams work towards this date all year to record and achieve the maximum patient care as all indicators are automatically ‘reset’ on the following day - 1st April.

Practice managers were asked to indicate the total number of patients registered on their practice list and on each disease register. We decided to code ‘exception reported’ indicators as if they had been met - in other words that the specified care was ‘delivered’ to patients. We based this premise on the fact that exception reporting has historically accounted for ≤ 1.6% of all QOF costs [38] and we assumed that the suitability of the care described by an indicator would have been considered (if not delivered) for each patient during the exemption process.

Statistical analysis

Data were uploaded to and coded in Microsoft Office Excel 2007. All patient and practice identifiers were removed immediately, with practices being coded to enable feedback to be provided. Descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS v.17.0 to calculate each practice’s compliance as a percentage for the selected QOF indicators (bundle component) and the composite compliance for the selected clinical conditions (bundles). Overall compliance with care bundles (composite measures) and their components were calculated after adding the patients on each disease register of all the participating practices together.

Results

Care bundles (composite measures) and indicators

Five QOF clinical conditions fulfilled the pre-specified inclusion criteria: Stroke/TIA, secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD), diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (CKD) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The 24 retained indicators are shown in Table 2.

Response rate and demographics

A total of 12/14 practices agreed to participate. Nine practices were able to provide data in the format requested to allow meaningful analysis (64.3%). The combined patient population on the 31st March 2010 was 56,948. The prevalence of the selected clinical conditions in all practices was: CKD 3.4% (range 2.5% to 4.9%), stroke/TIA 2.2% (range 1.7% to 2.7%), diabetes mellitus 4.2% (range 3.6% to 5.5%), CVD 4.6% (range 4.2% to 6.2%) and COPD 2.3% (range 0.8% to 3.8%). Further demographic and disease register details of participating practices are shown in Table 3.

Composite measures and individual indicator compliance

The minimum and maximum payment thresholds for the selected indicators ranged from 40-50% and 60-90% respectively. All practices achieved the minimum threshold for all indicators and the vast majority also achieved the maximum threshold for most indicators.

The composite measures of the selected conditions (care bundles) varied for all practices and were as follows: CKD 69.0% (range 64.0-81.4%), stroke/TIA 74.1% (range 51.6% to 82.8%), Diabetes mellitus 58.4% (range 50.3% to 65.2%), CVD 64.0% (range 47.8% to 71.9%) and COPD 82.0 (range 47.9% to 95.8%). Care bundles with more components such as DM and CVD generally had lower compliance rates.

The diabetes mellitus care delivered by all practices as specified by individual indicators ranged from 82.9% (DM24) to 98.5% (DM15), yet overall care bundle compliance was substantially lower at 58.4%. In other words, 58.4% of all eligible patients received all the care specified by the bundle and 41.6% of patients did not receive one or more care components. For CVD care, individual indicator achievements ranged from 82.6% (CVD10) to 99.0% (CVD11) with 64.0% of patients receiving all specified care. The COPD care delivery was the most reliable, with 82.0% of patients receiving all components. However, overall the results suggest that the composite bundle approach highlights a greater level of variation within and between practices in evidence based care delivery and arguably therefore provides a more informed and discriminatory measure of care quality than the current, largely homogenous approach. The variation in the individual indicator and composite measures for each clinical condition and practice can be observed in Table 3.

Discussion

Main findings

This small study is the first known attempt to measure composite care delivery for specific clinical conditions in UK primary care using a care bundle approach. We identified five suitable clinical conditions for care bundles: COPD, CKD, DM, TIA/Stroke and CHD. Three to eight components were chosen and adapted from QOF indicators for each bundle. Compliance with individual bundle components was generally high, but substantially lower overall for the ‘all or nothing’ bundles. We would suggest that this ‘gap’ in performance may be a more valid reflection of the variation in expected care delivery at the patient level than current individual measures presently indicate.

The ‘gap‘ between component and care bundle compliance

There are at least five possible reasons for the observed ‘gap’ between individual component and overall bundle compliance. Firstly, the Framework financially incentivizes an individual indicator approach so this becomes the practice focus. Secondly, some components are easier to deliver than others. Thirdly, care bundle compliance (the composite measure) will always have a value equal to or lower than that of the indicator with the lowest performance - consequently there will always be a gap, although it is unknown whether or when the size of the ‘gap’ becomes of clinical significance. Fourthly, the ‘gap’ will usually increase exponentially with the rise in the number of bundle components. Finally, natural variation is inherent in all health care systems and will be affected by the effectiveness and efficiencies of local processes and team efforts.

Variation in care is introduced ‘naturally’ through different and often complex patient presentations and ‘artificially’ through individual clinician differences and priorities, extenuating circumstances and local systems. ‘Patient characteristics’ and ‘deprivation’ have previously been identified as the two factors which are strongly associated with variation (‘the gap’) in primary health care settings in Scotland [12], England [11, 13, 39], the Netherlands [40], Australia [41] and the USA [42].

The care ‘gap’ between components and care bundles in our study was observed for all clinical conditions and participating practices. This ‘gap’ (variation) may be at least partially accounted for by hidden patient and deprivation factors. The implication may be that the care bundle method may measure the gap but could not necessarily help to eliminate it.

In UK secondary care settings, reported compliance with a variety of clinical care bundles ranges from 19-52% [32, 33]. Low compliance rates have important patient safety implications, as a positive and significant association has been found between compliance rates and clinical outcomes such as mortality [27, 28, 32]. A similar association has not yet been shown for primary care. Although the participating practices’ compliance with all the selected bundles was ≥ 58% it is not known whether compliance can be compared meaningfully across settings and for different care bundles. It would also be desirable to determine to what degree different compliance levels may impact on clinical outcomes in primary care settings.

The QOF and care bundles

We adapted care bundles from the QOF, currently the most ambitious, comprehensive and largest P4P scheme and quality measure in international healthcare and a ‘natural experiment in progress’ [43]. Framework research and experience may therefore be applicable to our study findings. For example: the Framework can cause a ‘street lamp effect’, i.e. neglect of health care activity and clinical conditions which do not attract financial incentives; it can create a de-personalizing ‘box ticking culture’; it is vulnerable to data distortion and potential gaming; it is accelerating a transition to nurse-led primary care; there is tension between the different QOF roles as a quality improvement method, regulatory framework or remuneration mechanism; the Framework promotes simplicity over complexity and measurability over meaningfulness. These valid concerns could similarly be raised about the care bundle method, with no clear answers at present [19, 43–46].

The impact of QOF on clinical outcomes continues to be debated. There is no evidence of any ‘discernable effect’ on hypertension-related outcomes [47], while new depression indicators failed to improve disease detection or treatment [46]. In addition, associations between QOF measures and all-cause mortality and emergency admissions have been found to be ‘small and inconsistent’ [39]. On the other hand, evidence of improved care quality for patients with specific chronic diseases and a ‘trend towards improvement’ in process and outcome at least partly attributable to QOF have recently been reported [44, 48–50]. It is unclear what impact (if any) surrogate measures such as care bundles would have on clinical outcomes, how this could be feasibly measured and what period of time would be required.

‘Time-interval’ indicators have been proposed as an alternative and more reliable measure to ‘point-in-time’ indicators to assess care quality [51]. Performance is evaluated over a specified period rather than at a single point in time. Mabotuwana et al applied this approach to hypertension management and found it feasible but with lower measures for ‘interval indicators’ compared with point-in-time indicators. The differences, similarities and potential benefits of any one method, whether care bundles, time-interval or QQF indicators are unclear.

Care bundle implementation

The care bundle method may be a useful new care quality measure and help to reduce healthcare variation. It may also help to better differentiate the care quality of practices, given that their current QOF scores are now broadly comparable. To implement the bundle a number of challenges would have to be overcome, for example: resistance from practices who are financially disadvantaged by ‘lower’ measures than the current thresholds; accounting for ‘natural’ variation so that practices are not unfairly penalized; existing information technology systems would have to be redesigned; a full evaluation to identify both impact and unintended consequences (e.g. a proportion of patients may end up receiving ‘no care’) would be necessary. If this new measure is considered desirable, it would have to be promoted and incentivized.

Reducing variation in quality can decrease costs if the care ‘gap’ is large, but costs increase as the gap narrows until there is a net expense [52]. Evaluation of care bundle implementation in some secondary care settings has found them to be cost-effective [53]. However, implementing interventions require initial financial and resource investment. McNeill et al found that only 20/265 (12%) of acute medicine units in the UK had the minimum facilities to comply with the ‘surviving sepsis care bundle’ [34]. However, the applicability of care bundles in acute settings cannot be assumed to translate to QOF-bundled components because care packages over 9-15 month periods.

The financial implications of quality-reporting programmes vary greatly. The QOF ‘probably’ represents value for money [54]. Adapting the Framework’s reporting system to allow composite quality measures would require substantial investment and feasibility and acceptability concerns would have to be addressed. Known incentives that facilitate increased practice participation include: financial payments, staff training and providing technical support [54, 55].

Implementing care bundles and increasing compliance with them relies not only on individual health care professionals but even more on the availability of adequate resources, support systems and leadership. Aligning care bundles with larger quality improvement initiatives and providing related training also appears to be an important factor influencing success and impact [28]. These issues need to be considered if the care bundle approach is to be successfully implemented in primary care settings.

Exception reporting and threshold ceilings

The threshold ‘ceiling’ for maximum financial reward is set at ≤ 90% achievement. Practices could hypothetically ‘stop’ delivering care once they reach these thresholds without financial penalty. Our findings indicate that many indicators with relatively low achievement ceilings were still performed for the vast majority of patients which seems to suggest that thresholds are an unlikely reason for the observed ‘gap’.

Exception reporting has previously been found to be consistent across practices and regions and accounts for a tiny minority of cases [38]. Concerns that practices may be ‘gaming’ results through excessive or inappropriate exception reporting have not been substantiated. However, exception reporting combined with less than 100% maximum threshold targets introduce an incentive ceiling [18].

Strengths and limitations

Our findings are based on a small, convenience sample of practices. We did not take into account patient list size, geographical distribution (degree of remoteness), socio-economic class and level of deprivation or prevalence of disease. Our findings may still have wider application, as different degrees of remoteness, access and practice size do not significantly contribute to variation in care quality as measured by QOF results [56, 57]. A recent review found that inequalities in chronic disease management have largely persisted after introduction of QOF (even though quality of care may have increased) [58]. While deprivation is a major contributing cause to overall care, it has not been shown to affect QOF scores. For example, Hamilton et al found that the impact of QOF on diabetes mellitus care was comparable in affluent and deprived areas [59].

We decided to code exception reported indicators as if the described care had been delivered. The consequence was a ‘smaller’ compliance ‘gap’, but one that may have more acceptability to frontline staff. Exclusion systems have an important role to help militate against the potential impact of socio-economic, patient and other factors out-with the practice team’s control. Simple care processes are mitigated more than complex ones and the additional work required in deprived areas is not always being rewarded [60]. We therefore purposefully selected ‘simple’ care bundle components in preference to ‘complex’ ones where possible. We accept that there are many other potential care bundle topics for general practice. However we chose a pragmatic approach to give an initial indication on the feasibility of the concept as applied to QOF data. Others may have chosen alternative approaches and clinical topics for bundles.

Conclusions

Based on our small study, we believe that the care bundle approach to QOF data has the potential to provide a more insightful measure of the quality of evidence based care provision than the current approach which focuses on compliance with individual indicators rather than individual patients. However, issues around the feasibility and acceptability of the implementation of this method as part of routine general practices need to be explored.

Authors‘ contributions

CdW led on the study design and data collection, undertook statistical analysis and interpretation, and drafted the initial manuscript. JM contributed to study design, data collection and critical review of the manuscript. PB conceived the study idea, acquired funding and contributed to the study design and the drafting and critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

Hines S, Joshi MS: Variation in quality of care within health systems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008, 34 (6): 326-332.

Moore CL, McMullen MJ, Woolford SW, Berger BM: Clinical process variation: effect on quality and cost of care. Am J Manag Care. 2010, 16 (5): 385-392.

Jacobs B, Duncan JR: Improving quality and patient safety by minimizing unnecessary variation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009, 20 (2): 157-163. 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.10.031.

Selby JV, Schmittdiel JA, Lee J, Fung V, Thomas S, Smider N, et al: Meaningful variation in performance: what does variation in quality tell us about improving quality?. Med Care. 2010, 48 (2): 133-139. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c15a6e.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS: Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996, 312 (7023): 71-72. 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71.

Cinel I, Dellinger RP: Guidelines for severe infections: are they useful?. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006, 12 (5): 483-488. 10.1097/01.ccx.0000244131.15484.4e.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, et al: Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999, 282 (15): 1458-1465. 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458.

Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J: Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999, 318 (7182): 527-530. 10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527.

Resar RK: Making noncatastrophic health care processes reliable: Learning to walk before running in creating high-reliability organizations. Health Serv Res. 2006, 41 (4 Pt 2): 1677-1689.

Holmboe ES, Weng W, Arnold GK, Kaplan SH, Normand SL, Greenfield S, et al: The comprehensive care project: measuring physician performance in ambulatory practice. Health Serv Res. 2010, 45 (6 Pt 2): 1912-1933.

Tsimtsiou Z, Ashworth M, Jones R: Variations in anxiolytic and hypnotic prescribing by GPs: a cross-sectional analysis using data from the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework. Br J Gen Pract. 2009, 59 (563): e191-e198. 10.3399/bjgp09X420923.

Morrison J, Anderson MJ, Sutton M, Munoz-Arroyo R, McDonald S, Maxwell M, et al: Factors influencing variation in prescribing of antidepressants by general practices in Scotland. Br J Gen Pract. 2009, 59 (559): e25-e31. 10.3399/bjgp09X395076.

Wang KY, Seed P, Schofield P, Ibrahim S, Ashworth M: Which practices are high antibiotic prescribers? A cross-sectional analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2009, 59 (567): e315-e320. 10.3399/bjgp09X472593.

Lester H, Campbell S: Developing Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) indicators and the concept of ‘QOFability’. Qual Prim Care. 2010, 18 (2): 103-109.

British Medical Association: Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance for GMS contract 2009-2010: delivering investment in general practice. 2009, Available at: http://www.bma.org.uk/images/qof0309_tcm41-184025.pdf. Accessed 06/11, 2011

The Information Centre: Domain Summary: Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) for April 2009 - March 2010, England. 2011. 11, Available at: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/QOF/2009-10/National%20tables/QOF0910_National_DomainSummary.xls. Accessed 11/16, 2011

Information Services Division Scotland.Quality and Outcomes Framework: 2009/10 Achievement at Scotland and NHS Board level. 2011, Available at: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/General-Practice/Quality-And-Outcomes-Framework/2009-10/. Accessed 11/16, 2011

Fleetcroft R, Steel N, Cookson R, Howe A: Mind the gap! Evaluation of the performance gap attributable to exception reporting and target thresholds in the new GMS contract: National database analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008, 8: 131-10.1186/1472-6963-8-131.

Ashworth M, Kordowicz M: Quality and Outcomes Framework: smoke and mirrors?. Qual Prim Care. 2010, 18 (2): 127-131.

Marwick C, Davey P: Care bundles: the holy grail of infectious risk management in hospital?. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009, 22 (4): 364-369. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832e0736.

Resar R, Pronovost P, Haraden C, Simmonds T, Rainey T, Nolan T: Using a bundle approach to improve ventilator care processes and reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005, 31 (5): 243-248.

Hitchen L: England launches scheme to encourage use of “care bundles”. BMJ. 2008, 336 (7639): 294-295.

Haraden C: What is a bundle?. 2011, Available at: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/ImprovementStories/WhatIsaBundle.htm. Accessed 06/09, 2011

Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Ngo K, McDowell M, Holzmueller C, Haraden C, et al: Developing and pilot testing quality indicators in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2003, 18 (3): 145-155. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2003.08.003.

Wip C, Napolitano L: Bundles to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia: how valuable are they?. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009, 22 (2): 159-166. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283295e7b.

Crunden E, Boyce C, Woodman H, Bray B: An evaluation of the impact of the ventilator care bundle. Nurs Crit Care. 2005, 10 (5): 242-246. 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2005.00134.x.

Carter C: Implementing the severe sepsis care bundles outside the ICU by outreach. Nurs Crit Care. 2007, 12 (5): 225-230. 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2007.00242.x.

Robb E, Jarman B, Suntharalingam G, Higgens C, Tennant R, Elcock K: Using care bundles to reduce in-hospital mortality: quantitative survey. BMJ. 2010, 340: 1234-10.1136/bmj.c1234.

Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L, Cohen BA, Prengler ID, Cheng D, et al: Reduction of 30-day post discharge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med. 2009, 4 (4): 211-218. 10.1002/jhm.427.

Duffin C: Introduction of ‘care bundles’ reduces patient mortality rates by 15 per cent. Nurs Manage (London). 2010, 17 (2): 7.

Guerin K, Wagner J, Rains K, Bessesen M: Reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infections by implementation of a post insertion care bundle. Am J Infect Control. 2010, 38 (6): 430-433. 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.03.007.

Gao F, Melody T, Daniels DF, Giles S, Fox S: The impact of compliance with 6-hour and 24-hour sepsis bundles on hospital mortality in patients with severe sepsis: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2005, 9 (6): R764-R770. 10.1186/cc3909.

Baldwin LN, Smith SA, Fender V, Gisby S, Fraser J: An audit of compliance with the sepsis resuscitation care bundle in patients admitted to A&E with severe sepsis or septic shock. Int Emerg Nurs. 2008, 16 (4): 250-256. 10.1016/j.ienj.2008.05.008.

McNeill G, Dixon M, Jenkins P: Can acute medicine units in the UK comply with the Surviving Sepsis Campaign’s six-hour care bundle?. Clin Med. 2008, 8 (2): 163-165.

Nolan JP, Soar J: Post resuscitation care–time for a care bundle?. Resuscitation. 2008, 76 (2): 161-162. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.12.005.

Guthrie B: Measuring the quality of healthcare systems using composites. BMJ. 2008, 337: a639-10.1136/bmj.a639.

Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, Emery J, Farmer A, Griffiths F, et al: Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ. 2007, 334 (7591): 455-459. 10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE.

Doran T, Fullwood C, Reeves D, Gravelle H, Roland M: Exclusion of patients from pay-for-performance targets by English physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008, 359 (3): 274-284. 10.1056/NEJMsa0800310.

Downing A, Rudge G, Cheng Y, Tu YK, Keen J, Gilthorpe MS: Do the UK government’s new Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) scores adequately measure primary care performance? A cross-sectional survey of routine healthcare data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007, 7: 166-10.1186/1472-6963-7-166.

Lingsma HF, Dippel DW, Hoeks SE, Steyerberg EW, Franke CL, van Oostenbrugge RJ, et al: Variation between hospitals in patient outcome after stroke is only partly explained by differences in quality of care: results from the Netherlands Stroke Survey. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008, 79 (8): 888-894. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.137059.

Si D, Bailie R, Dowden M, Kennedy C, Cox R, O’Donoghue L, et al: Assessing quality of diabetes care and its variation in Aboriginal community health centres in Australia. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010, 26 (6): 464-473. 10.1002/dmrr.1062.

O’Connor PJ, Rush WA, Davidson G, Louis TA, Solberg LI, Crain L, et al: Variation in quality of diabetes care at the levels of patient, physician, and clinic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008, 5 (1): A15.

Gillam S, Siriwardena AN: The quality and outcomes framework: triumph of technical rationality, challenge for individual care?. Qual Prim Care. 2010, 18 (2): 81-83.

Steel N, Willems S: Research learning from the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework: a review of existing research. Qual Prim Care. 2010, 18 (2): 117-125.

Williams PH, de Lusignan S: Does a higher ‘quality points’ score mean better care in stroke? An audit of general practice medical records. Inform Prim Care. 2006, 14 (1): 29-40.

Subramanian DN, Hopayian K: An audit of the first year of screening for depression in patients with diabetes and ischaemic heart disease under the Quality and Outcomes Framework. Qual Prim Care. 2008, 16 (5): 341-344.

Serumaga B, Ross-Degnan D, Avery AJ, Elliott RA, Majumdar SR, Zhang F, et al: Effect of pay for performance on the management and outcomes of hypertension in the United Kingdom: interrupted time series study. BMJ. 2011, 342: 108-10.1136/bmj.d108.

Campbell S, Reeves D, Kontopantelis E, Middleton E, Sibbald B, Roland M: Quality of primary care in England with the introduction of pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357 (2): 181-190. 10.1056/NEJMsr065990.

Khunti K, Gadsby R, Millett C, Majeed A, Davies M: Quality of diabetes care in the UK: comparison of published quality-of-care reports with results of the Quality and Outcomes Framework for diabetes. Diabet Med. 2007, 24 (12): 1436-1441. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02276.x.

Oluwatowoju I, Abu E, Wild SH, Byrne CD: Improvements in glycaemic control and cholesterol concentrations associated with the Quality and Outcomes Framework: a regional 2-year audit of diabetes care in the UK. Diabet Med. 2010, 27 (3): 354-359. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02951.x.

Mabotuwana T, Warren J, Elley CR, Kennelly J, Paton C, Warren D, et al: Use of interval based quality indicators in blood pressure managment to enhance quality of pay for performance incentives: comparison to two indicators from the Quality and Outcomes Framework. QPC. 2010, 18: 93-100.

Peabody JW, Florentino J, Shimkhada R, Solon O, Quimbo S: Quality variation and its impact on costs and satisfaction: evidence from the QIDS study. Med Care. 2010, 48 (1): 25-30. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd47b2.

Halton KA, Cook D, Paterson DL, Safdar N, Graves N: Cost-effectiveness of a central venous catheter care bundle. PLoS ONE . 2010, 5 (9): e12815-10.1371/journal.pone.0012815. Electronic Resource

Walker S, Mason AR, Claxton K, Cookson R, Fenwick E, Fleetcroft R, et al: Value for money and the Quality and Outcomes Framework in primary care in the UK NHS. Br J Gen Pract. 2010, 60 (574): e213-e220. 10.3399/bjgp10X501859.

Halladay JR, Stearns SC, Wroth T, Spragens L, Hofstetter S, Zimmerman S, et al: Cost to primary care practices of responding to payer requests for quality and performance data. Ann Fam Med. 2009, 7 (6): 495-503. 10.1370/afm.1050.

McLean G, Guthrie B, Sutton M: Differences in the quality of primary medical care services by remoteness from urban settlements. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007, 16 (6): 446-449. 10.1136/qshc.2006.020875.

Doran T, Campbell S, Fullwood C, Kontopantelis E, Roland M: Performance of small general practices under the UK’s Quality and Outcomes Framework. Br J Gen Pract. 2010, 60 (578): e335-e344. 10.3399/bjgp10X515340.

Alshamsan R, Majeed A, Ashworth M, Car J, Millett C: Impact of pay for performance on inequalities in health care: systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010, 15 (3): 178-184. 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.009113.

Hamilton FL, Bottle A, Vamos EP, Curcin V, Anthea , Molokhia M, et al: Impact of a pay-for-performance incentive scheme on age, sex, and socioeconomic disparities in diabetes management in UK primary care. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2010, 33 (4): 336-349.

McLean G, Sutton M, Guthrie B: Deprivation and quality of primary care services: evidence for persistence of the inverse care law from the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006, 60 (11): 917-922. 10.1136/jech.2005.044628.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/12/351/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the GPs and Practice Managers who assisted us with this pilot and Dr Paul Johnson of the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow for initial statistical advice. We also thank our employing organisation, NHS Education for Scotland, for providing study funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Carl de Wet, John McKay and Paul Bowie contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Wet, C., McKay, J. & Bowie, P. Combining QOF data with the care bundle approach may provide a more meaningful measure of quality in general practice. BMC Health Serv Res 12, 351 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-351

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-351