Abstract

Background

To ensure evidence-based decision-making in pediatric oral health, Cochrane systematic reviews that address topics pertinent to this field are necessary. We aimed to identify all systematic reviews of paediatric dentistry and oral health by the Cochrane Oral Health Group (COHG), summarize their characteristics and assess their methodological quality. Our second objective was to assess implications for practice in the review conclusions and provide an overview of clinical implications about the usefulness of paediatric oral health interventions in practice.

Methods

We conducted a methodological survey including all paediatric dentistry reviews from the COHG. We extracted data on characteristics of included reviews, then assessed the methodological quality using a validated 11-item quality assessment tool (AMSTAR). Finally, we coded each review to indicate whether its authors concluded that an intervention should be implemented in practice, was not supported or was refuted by the evidence, or should be used only in research (inconclusive evidence).

Results

We selected 37 reviews; most concerned the prevention of caries. The methodological quality was high, except for the assessment of reporting bias. In 7 reviews (19%), the research showed that benefits outweighed harms; in 1, the experimental intervention was found ineffective; and in 29 (78%), evidence was insufficient to assess benefits and harms. In the 7 reviews, topical fluoride treatments (with toothpaste, gel or varnish) were found effective for permanent and deciduous teeth in children and adolescents, and sealants for occlusal tooth surfaces of permanent molars.

Conclusions

Cochrane reviews of paediatric dentistry were of high quality. They provided strong evidence that topical fluoride treatments and sealants are effective for children and adolescents and thus should be implemented in practice. However, a substantial number of reviews yielded inconclusive evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Evidence-based dentistry has contributed substantially to improving the quality of oral health in general and in the paediatric population in particular. Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the highest standard in evidence-based healthcare available to clinicians to guide clinical practice. The Cochrane Collaboration is the world’s largest producer of systematic reviews of primary research in human health care and health policy [1]. The Cochrane Oral Health Group (COHG) is one of 50 review groups within the Cochrane Collaboration.

High methodological quality is necessary for valid interpretation and application of systematic review findings [2, 3]. Moreover, systematic reviews can be a source of knowledge for healthcare practice, provided that they give conclusive evidence that interventions are effective, ineffective or harmful. To our knowledge, no study has assessed the methodological quality and implications for practice of Cochrane systematic reviews of paediatric oral health.

We aimed to identify all existing systematic reviews of the COHG related to paediatric dentistry and oral health and to summarize the most relevant characteristics of the reviews. Our second objective was to evaluate the methodological quality of the systematic reviews using A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR), a validated 11-item quality assessment tool. Finally, we aimed to assess the implications for practice in the review conclusions and provide an overview of clinical implications about the usefulness of paediatric oral health interventions in practice.

Methods

We conducted a methodological survey including all paediatric reviews indexed in the Dentistry and Oral Health category of the COHG reviews. We extracted data on characteristics of included Cochrane reviews, then assessed the methodological quality using the AMSTAR checklist. Finally, we examined the review conclusions to assess whether the experimental intervention was conclusive, ineffective, harmful or contained inconclusive evidence.

Criteria for considering systematic reviews

Eligible systematic reviews were of paediatric dentistry and oral health produced by the COHG. In the first step, we selected systematic reviews if the authors clearly reported participants as “children” or “adolescents” in the title and objectives. If this was not clear, we systematically examined the full text of selected articles to determine whether authors defined an upper age limit as selection criteria or whether the maximum age of included patients was ≤ 18 years old. We selected updates of systematic reviews rather than initial versions. We excluded systematic reviews that included at least one RCT of adults and reviews that did not mention the age of participants.

Search methods for systematic reviews

We identified eligible Cochrane systematic reviews indexed in the Dentistry and Oral Health category of the COHG at http://www.thecochranelibrary.com. The last search was conducted in November 2013. Two authors independently and in duplicate screened all full-text reports. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

Characteristics of included Cochrane systematic reviews

Two reviewers extracted data independently and in duplicate, with discrepancies resolved by discussion. For each systematic review, we recorded the publication year, the country, the topic, the participants and the primary outcomes. For each meta-analysis of primary outcomes, we recorded the experimental intervention, the comparator, the number of RCTs examined, the number of participants, and the relative effect (treatment effect measure and combined estimate [95% confidence interval]).

Assessment of methodological quality of Cochrane systematic reviews

Two reviewers independently and in duplicate evaluated the methodological quality of systematic reviews using the AMSTAR checklist, a measurement tool of 11 items [4, 5]. Disagreements were resolved with a third author. We did not use the PRISMA checklist because it is not intended to be a quality assessment tool as compared with the AMSTAR, which is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews [5, 6]. The following characteristics were assessed: a priori design, study selection and data extraction, literature search, status of publication, characteristics of the included and excluded studies, scientific quality of the included studies, methods used to combine the findings of studies, publication bias and conflict of interest.

Assessment of the implications for practice in conclusions sections of Cochrane systematic reviews

Two reviewers independently examined the implications-for-practice paragraph in the conclusions sections of all selected systematic reviews. Disagreements were resolved by a third author. For each review, we assessed whether the experimental intervention should be implemented in practice (ie, conclusive evidence that the intervention was effective and not harmful), was ineffective and should not be used in practice, was harmful and should not be used in practice, or should be used only in research (ie, the evidence identified was inconclusive; that is, the intervention could be beneficial or harmful) [7, 8]. The experimental intervention was considered ineffective if the evidence showed that it was ineffective for all primary outcomes, harmful if the evidence showed it was harmful for at least one adverse event, to be used in research only if the evidence was inconclusive for at least one primary outcome, or should be implemented in practice if the evidence showed that it was effective for all primary outcomes and not harmful, with no adverse events.

Results

Eligible Cochrane systematic reviews

The search yielded 278 Cochrane systematic reviews that specifically addressed dentistry and oral health issues. After 7 duplicates were removed, we finally included 37 systematic reviews focused on paediatric oral health [9–45].

Characteristics of included Cochrane systematic reviews

The median year of publication was 2008 (range 2002–2013) (Table 1). Most systematic reviews (57%) were performed in the United Kingdom. The reviews mainly concerned interventions for the prevention of dental caries (n = 16), orthodontic treatment and oral surgery (n = 4 for each domain), treatment of dental caries (n = 3) and behavior management (n = 2). Details are given in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Comparisons of primary outcomes

In 30 reviews, no meta-analysis was performed for primary outcomes in 65 comparisons: for 9 comparisons, no RCT existed for the primary outcomes; for 53 comparisons, only 1 RCT existed for the primary outcomes; and for 3 comparisons (2, 3, and 3 RCTs), no meta-analysis was performed for the primary outcomes. In 15 reviews, 65 meta-analyses were performed for primary outcomes (at least 2 RCTs included). Among the 65 meta-analyses, the median number of RCTs per meta-analysis was 3 [Q1–Q3 2–6, min–max 2–133] and the median number of patients per meta-analysis was 360 [Q1–Q3 182–1,673, min–max 50–65,179]. The number of meta-analyses with continuous outcomes was 61 (94%). Details are given in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Methodological quality of Cochrane systematic reviews

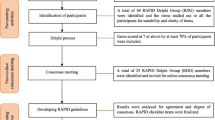

The overall quality of the selected reviews was high according to the AMSTAR checklist. In all reviews, the reporting of 8 of the 11 items was adequate (Figure 1). The weakest area was failure to report the likelihood of publication bias, in 14 reviews (38%), which did not assess publication bias [11–13, 17, 19, 20, 24–26, 34, 35, 38, 42, 43]. One review did not use “grey” literature as an inclusion criterion [34] and in another, the methods used to combine the findings of studies were inappropriate [38].

Implications for practice in Cochrane systematic reviews

For the 37 systematic reviews, 7 (19%) concluded that specific interventions should be implemented in practice (ie, interventions for which research showed that benefits outweighed harms), and 1 concluded that specific interventions should not be used in practice because of ineffectiveness (Table 2). All experimental interventions that had been shown to be effective involved prevention of dental caries. Research evidence supported the effectiveness of topical fluoride treatments (with toothpaste, gel or varnish) for permanent and deciduous teeth in children and adolescents, and sealants for occlusal tooth surfaces of permanent molars. We did not identify any intervention for which research showed that harms outweighed benefits. However, for 29 reviews (78%), the evidence was inconclusive because it was limited (see Additional file 3: Table S3).

Discussion

Our study shows that the number of Cochrane systematic reviews in paediatric dentistry and oral health has increased during the last few years. This situation should improve the basis for clinical decision-making because systematic reviews are considered essential sources of evidence for guideline development [46]. The methodological quality of most of our reviews was high, corresponding to the high quality standards of the Cochrane Collaboration. Nevertheless, the likelihood of publication bias was not frequently assessed. This is an important factor to take into account in the conduct of a meta-analysis and in the interpretation of results [47].

Cochrane reviews should not define recommendations for practice because this requires assumptions about the relative importance of benefits and harms of an intervention and judgements that are beyond the scope of a systematic review. However, Cochrane review authors always propose implications for practice. Our study demonstrated that most of the reviews (43%) and all interventions supported by research evidence focused on the prevention of dental caries. For children and adolescents, topical fluoride treatments (with toothpaste, gel or varnish) were found effective for permanent and deciduous teeth and sealants for occlusal tooth surfaces of permanent molars. The predominance of this topic seems justified because it is the most important from a public health policy viewpoint. Early childhood caries is the most frequent chronic disease affecting young children and is 5 times more common than asthma [48]. The selected reviews also concerned orthodontic treatment and oral surgery. However, for clinicians, several secondary research gaps are the management of oro-dental trauma or conservative treatments. Actually, the latter involve materials that may be harmful because of some toxicity [49, 50].

Many of our reviews (78%) produced inconclusive evidence. The most common reasons for failure to provide reliable information to guide clinical decisions are the small numbers of RCTs and patients per meta-analysis. According to a cross-sectional descriptive analysis about characteristics of meta-analyses in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the median number of RCTs included in meta-analyses was 3 (Q1–Q3 2–6) and the median number of patients was 91 (Q1–Q3 44–210) [51]. Our findings are consistent with these figures and emphasize that more high-quality primary research may be frequently needed to reach conclusiveness. However, none of the selected reviews was empty; that is, randomized evidence always existed and was included in the review, even when inconclusive. Another explanation for the inconclusiveness may be the inability to perform data synthesis. Diversity in outcomes measured across RCTs within a review may substantially limit the ability to perform meta-analyses and may explain the lack of recommendations [52, 53]. Many meta-analyses frequently exclude a large number of RCTs because outcomes are too different between studies [54]. The standardization of outcomes was initiated by the OMERACT group [55] and is expanding with the COMET Initiative [56]. In the field of dentistry, some studies have defined core outcome sets to help solve this problem, such as in implantology [57–60] and for the evaluation of pulp treatments in primary teeth [61]. Finally, all systematic reviews should be considered as informative because they may allow for identifying well-informed uncertainties about the effects of treatments [62, 63].

Previous methodological surveys assessed the conduct quality of systematic reviews in the field of dentistry [64–66]. In a study of 109 systematic reviews published in major orthodontic journals, 26 were published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. In all, 21% of the selected reviews satisfied 9 or more of the 11 AMSTAR criteria [64, 65]. However, to our best knowledge, no methodological survey concerned specifically pediatric oral health.

Our study has some limitations. Indeed, we considered only Cochrane systematic reviews in our study, but many non-Cochrane systematic reviews have also assessed interventions in the paediatric oral health field [67]. Nevertheless, Cochrane systematic reviews are the highest standard in evidence-based health care. Moreover, Cochrane reviews have a standard structure, which always includes implications for practice. Another potential limitation is that we assessed whether the experimental intervention should be used in practice, should not be used in practice or should be used only in research based on the Implications-for-practice section only and we did not critically judge the review evidence ourselves. However, Cochrane review authors describe clinical implications only after describing the quality of evidence and the balance of benefits and harms.

Conclusions

The Cochrane reviews of paediatric dentistry and oral health were of high quality. They provided strong evidence that topical fluoride treatments and sealants are effective for children and adolescents and thus should be implemented in practice. However, a substantial number of reviews yielded inconclusive findings.

References

Higgins J, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. 2011, The Cochrane Collaboration, Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S: Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: an annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials. 1995, 16 (1): 62-73. 10.1016/0197-2456(94)00031-W.

Mulrow CD: Rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994, 309 (6954): 597-599. 10.1136/bmj.309.6954.597.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM: Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007, 7: 10-10.1186/1471-2288-7-10.

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson E, Grimshaw J, Henry DA, Boers M: AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009, 62 (10): 1013-1020. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D: The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6 (7): e1000100-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Garner S, Docherty M, Somner J, Sharma T, Choudhury M, Clarke M, Littlejohns P: Reducing ineffective practice: challenges in identifying low-value health care using Cochrane systematic reviews. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013, 18 (1): 6-12. 10.1258/jhsrp.2012.012044.

Clarke M, Clarke T, Clarke L: Cochrane systematic reviews as a source of information for practice and trials. Trials. 2011, 12 (Suppl 1): A49-10.1186/1745-6215-12-S1-A49.

Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Forss H, Walsh T, Hiiri A, Nordblad A, Makela M, Worthington HV: Sealants for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, , 3, CD001830

Al-Harasi S, Ashley PF, Moles DR, Parekh S, Walters V: Hypnosis for children undergoing dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, , 8, CD007154

Ashley PF, Parekh S, Moles DR, Anand P, Behbehani A: Preoperative analgesics for additional pain relief in children and adolescents having dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, , 9, CD008392

Ashley PF, Williams CE, Moles DR, Parry J: Sedation versus general anaesthesia for provision of dental treatment in under 18 year olds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, , 11, CD006334

Beirne P, Clarkson JE, Worthington HV: Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, , 4, CD004346

Belmonte FM, Macedo CR, Day PF, Saconato H, Fernandes Moca Trevisani V: Interventions for treating traumatised permanent front teeth: luxated (dislodged) teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, , 4, CD006203

Benson PE, Parkin N, Millett DT, Dyer FE, Vine S, Shah A: Fluorides for the prevention of white spots on teeth during fixed brace treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004, , 3, CD003809

Bessell A, Hooper L, Shaw WC, Reilly S, Reid J, Glenny AM: Feeding interventions for growth and development in infants with cleft lip, cleft palate or cleft lip and palate. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, , 2, CD003315

Bonner BC, Clarkson JE, Dobbyn L, Khanna S: Slow-release fluoride devices for the control of dental decay. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, , 4, CD005101

Carvalho FR, Lentini-Oliveira D, Machado MA, Prado GF, Prado LB, Saconato H: Oral appliances and functional orthopaedic appliances for obstructive sleep apnoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, , 2, CD005520

Cooper AM, O’Malley LA, Elison SN, Armstrong R, Burnside G, Adair P, Dugdill L, Pine C: Primary school-based behavioural interventions for preventing caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, , 5, CD009378

Dashash M, Yeung CA, Jamous I, Blinkhorn A: Interventions for the restorative care of amelogenesis imperfecta in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, , 6, CD007157

Guo J, Li C, Zhang Q, Wu G, Deacon SA, Chen J, Hu H, Zou S, Ye Q: Secondary bone grafting for alveolar cleft in children with cleft lip or cleft lip and palate. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, , 6, CD008050

Harrison JE, O’Brien KD, Worthington HV: Orthodontic treatment for prominent upper front teeth in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, , 3, CD003452

Hiiri A, Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Nordblad A, Makela M: Pit and fissure sealants versus fluoride varnishes for preventing dental decay in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, , 3, CD003067

Innes NP, Ricketts DN, Evans DJ: Preformed metal crowns for decayed primary molar teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, , 1, CD005512

Lentini-Oliveira D, Carvalho FR, Qingsong Y, Junjie L, Saconato H, Machado MA, Prado LB, Prado GF: Orthodontic and orthopaedic treatment for anterior open bite in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, , 2, CD005515

Lourenco-Matharu L, Ashley PF, Furness S: Sedation of children undergoing dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, , 3, CD003877

Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A: Fluoride gels for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002, , 2, CD002280

Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A: Topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouthrinses, gels or varnishes) for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003, , 4, CD002782

Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A: Fluoride mouthrinses for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003, , 3, CD002284

Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Sheiham A, Logan S: Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003, , 1, CD002278

Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Sheiham A, Logan S: Combinations of topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouthrinses, gels, varnishes) versus single topical fluoride for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004, , 1, CD002781

Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Sheiham A, Logan S: One topical fluoride (toothpastes, or mouthrinses, or gels, or varnishes) versus another for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004, , 1, CD002780

Marinho VC, Worthington HV, Walsh T, Clarkson JE: Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, , 7, CD002279

Mettes TD, Ghaeminia H, Nienhuijs ME, Perry J, van der Sanden WJ, Plasschaert A: Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, , 6, CD003879

Millett DT, Cunningham SJ, O’Brien KD, Benson P, Williams A, de Oliveira CM: Orthodontic treatment for deep bite and retroclined upper front teeth in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, , 4, CD005972

Nadin G, Goel BR, Yeung CA, Glenny AM: Pulp treatment for extensive decay in primary teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003, , 1, CD003220

Nasser M, Fedorowicz Z, Khoshnevisan MH, Shahiri Tabarestani M: Acyclovir for treating primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, , 4, CD006700

Nasser M, Fedorowicz Z, Newton JT, Nouri M: Interventions for the management of submucous cleft palate. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, , 1, CD006703

Parkin N, Benson PE, Thind B, Shah A: Open versus closed surgical exposure of canine teeth that are displaced in the roof of the mouth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, , 4, CD006966

Parkin N, Furness S, Shah A, Thind B, Marshman Z, Glenroy G, Dyer F, Benson PE: Extraction of primary (baby) teeth for unerupted palatally displaced permanent canine teeth in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, , 12, CD004621

Tubert-Jeannin S, Auclair C, Amsallem E, Tramini P, Gerbaud L, Ruffieux C, Schulte AG, Koch MJ, Rege-Walther M, Ismail A: Fluoride supplements (tablets, drops, lozenges or chewing gums) for preventing dental caries in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, , 12, CD007592

Walsh T, Worthington HV, Glenny AM, Appelbe P, Marinho VC, Shi X: Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, , 1, CD007868

Wong MC, Glenny AM, Tsang BW, Lo EC, Worthington HV, Marinho VC: Topical fluoride as a cause of dental fluorosis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, , 1, CD007693

Yengopal V, Harneker SY, Patel N, Siegfried N: Dental fillings for the treatment of caries in the primary dentition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, , 2, CD004483

Yeung CA, Hitchings JL, Macfarlane TV, Threlfall AG, Tickle M, Glenny AM: Fluoridated milk for preventing dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005, , 3, CD003876

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Harbour RT, Haugh MC, Henry D, Hill S, Jaeschke R, Leng G, Liberati A, Magrini N, Mason J, Middleton P, Mrukowicz J, O’Connell D, Oxman AD, Phillips B, Schünemann HJ, Edejer T, Varonen H, Vist GE, Williams JW, Zaza S, GRADE Working Group: Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004, 328 (7454): 1490-

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997, 315 (7109): 629-634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629.

Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2000, 28 (9): 685-695.

Goldberg M: In vitro and in vivo studies on the toxicity of dental resin components: a review. Clin Oral Investig. 2008, 12 (1): 1-8. 10.1007/s00784-007-0162-8.

Koral SM: Mercury from dental amalgam: exposure and risk assessment. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2013, 34 (2): 138-140. 142, 144 passim

Davey J, Turner RM, Clarke MJ, Higgins JP: Characteristics of meta-analyses and their component studies in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: a cross-sectional, descriptive analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011, 11: 160-10.1186/1471-2288-11-160.

Clarke M: Standardising outcomes for clinical trials and systematic reviews. Trials. 2007, 8: 39-10.1186/1745-6215-8-39.

Williamson P, Clarke M: The COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative: its role in improving cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, , 5, ED000041

Furukawa TA, Watanabe N, Omori IM, Montori VM, Guyatt GH: Association between unreported outcomes and effect size estimates in Cochrane meta-analyses. JAMA. 2007, 297 (5): 468-470.

Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, Idzerda L: OMERACT: an international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007, 8: 38-10.1186/1745-6215-8-38.

Williamson P, Altman D, Blazeby J, Clarke M, Gargon E: Driving up the quality and relevance of research through the use of agreed core outcomes. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012, 17 (1): 1-2. 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011131.

Carr A, Wolfaardt J, Garrett N: Capturing patient benefits of treatment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011, 26 (Suppl): 85-92. discussion 101-102

Faggion CM, Listl S, Tu YK: Assessment of endpoints in studies on peri-implantitis treatment–a systematic review. J Dent. 2010, 38 (6): 443-450. 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.03.003.

Needleman I, Chin S, O’Brien T, Petrie A, Donos N: Systematic review of outcome measurements and reference group(s) to evaluate and compare implant success and failure. J Clin Periodontol. 2012, 39 (Suppl 12): 122-132.

Papaspyridakos P, Chen CJ, Singh M, Weber HP, Gallucci GO: Success criteria in implant dentistry: a systematic review. J Dent Res. 2012, 91 (3): 242-248. 10.1177/0022034511431252.

Smail-Faugeron V, Fron Chabouis H, Durieux P, Attal JP, Muller-Bolla M, Courson F: Development of a core set of outcomes for randomized controlled trials with multiple outcomes–example of pulp treatments of primary teeth for extensive decay in children. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (1): e51908-10.1371/journal.pone.0051908.

Chalmers I: Well informed uncertainties about the effects of treatments. BMJ. 2004, 328 (7438): 475-476. 10.1136/bmj.328.7438.475.

Chalmers I: Systematic reviews and uncertainties about the effects of treatments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011, , 2011, ED000004

Fleming PS, Seehra J, Polychronopoulou A, Fedorowicz Z, Pandis N: Cochrane and non-Cochrane systematic reviews in leading orthodontic journals: a quality paradigm?. Eur J Orthod. 2013, 35 (2): 244-248. 10.1093/ejo/cjs016.

Fleming PS, Seehra J, Polychronopoulou A, Fedorowicz Z, Pandis N: A PRISMA assessment of the reporting quality of systematic reviews in orthodontics. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83 (1): 158-163. 10.2319/032612-251.1.

Sequeira-Byron P, Fedorowicz Z, Jagannath VA, Sharif MO: An AMSTAR assessment of the methodological quality of systematic reviews of oral healthcare interventions published in the Journal of Applied Oral Science (JAOS). J Appl Oral Sci. 2011, 19 (5): 440-447. 10.1590/S1678-77572011000500002.

ADA. Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/14/35/prepub

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Smales (BioMedEditing, Toronto, Canada) for editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

VSF drafted the manuscript. HFC and FC participated in the design of the study. All authors conceived of the study, read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Smaïl-Faugeron, V., Fron-Chabouis, H. & Courson, F. Methodological quality and implications for practice of systematic Cochrane reviews in pediatric oral health: a critical assessment. BMC Oral Health 14, 35 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-14-35

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-14-35