Abstract

Background

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are ubiquitous environmental contaminants that have been banned in most countries, but considerable amounts continue to cycle the ecosphere. Top trophic level predators, like sea birds and marine mammals, bioaccumulate these lipophilic compounds, reflecting their presence in the environment.

Results

We measured concentrations of tDDT (p,p' - DDT + p,p' - DDD + p,p' - DDE) and PCBs in the blubber of dead California sea lions stranded along the California coast. tDDT and PCB concentrations were 150 ± 257 ug/g lipid weight (mean ± SD) and 44 ± 78 ug/g lipid weight, respectively. There were no differences in tDDT or PCB concentrations between animal categories varying in sex or age. There was a trend towards a decrease in tDDT and PCB concentrations from northern to southern California. The lipid content of the blubber was negatively correlated with levels of tDDT and PCBs. tDDT concentrations were approximately 3 times higher than PCB concentrations.

Conclusions

tDDT levels in the blubber of California sea lions decreased by over one order of magnitude from 1970 to 2000. PCB level changes over time were unclear owing to a paucity of data and analytical differences over the years. Current levels of these pollutants in California sea lions are among the highest among marine mammals and exceed those reported to cause immunotoxicity or endocrine disruption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The California sea lion, Zalophus californianus californianus, is a useful sentinel for monitoring levels of fat-soluble contaminants in the coastal waters of the western United States. As long-lived, apex predators at the top of a complex ocean food web, with high body lipid content, they become sinks for organochlorines such as PCBs and DDT that, because of their high lipophilicity and persistency, have accumulated in the marine food chain for several decades [1–4].

Outside Mexico and the Galapagos Islands, the main breeding rookeries of California sea lions are in the Channel Islands in southern California. Pupping occurs from mid-May through June, and breeding follows from July through mid-August. Females remain close to the natal rookery for 6 to 11 months, alternating nursing their pups on the rookery for 1–2 days with foraging trips at sea lasting 2–3 days. In late summer, after breeding, adult and subadult males migrate north along the coast, returning to the rookeries the following summer [5, 6]. The distance of migration increases with age, with some adult males migrating as far as British Columbia, Canada. Some non lactating females also leave the rookeries and move up to Central California [7].

The major contaminant pathways in marine mammals are via prenatal mother-offspring transfer and food consumption, including mother's milk. Much of a mother's contaminant load passes directly to her offspring, during nursing, especially to the first one [8–11]. Males, on the other hand, become increasingly contaminated as they grow older [12–14]. After weaning, most contaminants are obtained from consumption of contaminated prey. Organochlorine contaminants cause adverse effects such as immunotoxicity, carcinogenicity, growth and development abnormalities as well as reproductive impairment [4, 15]. Mass mortalities and declining stocks among several marine mammal populations from highly polluted areas have been attributed, in part, to contamination by organochlorine pollutants [12, 16–18].

Extraordinarily high levels of DDT were reported in California sea lions in the early 1970s [19]. From 1948 to 1970, the world's largest DDT manufacturer, discharged up to 20 tons of DDT wastes annually into the Los Angeles outfall on the Palos Verdes continental shelf in southern California; an estimated 156 tons of DDT residues remain, representing a potential, enduring source of contamination [20]. Since the manufacture of DDT and PCBs stopped in United States in the 1970s, few data have been collected subsequently on contaminant loads in California sea lions [but see [21, 22]]. In the present study, we address this omission by evaluating current levels of tDDT and PCBs in the blubber of stranded animals. We focus on geographical and temporal trends and the potential effects of sex and age categories and carcass condition on contaminant levels.

Results

We measured concentrations of tDDT (p,p' - DDT + p,p' - DDD + p,p' - DDE) and PCBs in blubber tissue samples collected from 36 dead California sea lions stranded on islands and the coast of California between April and November, 2000 (Table 1).

Lipid content in blubber was 50 ± 24 % (Mean ± SD). Levels were as low as 2–4% and as high as 87–88% of fat. Carcass condition had no significant effect on the lipid content of the blubber (F = 1.150; df = 2,31; p = 0.330).

The mean tDDT concentration (± SD) in blubber was 37 ± 27 μg/g wet weight and 150 ± 257 μg/g lipid weight. When the 5 samples with a lipid content < 20% were removed, the mean tDDT concentration was 41 ± 28 μg/g wet weight and 82 ± 74 μg/g lipid weight. DDE, DDD and DDT accounted for 98.0 ± 0.9, 1.7 ± 0.8, and 0.3 ± 0.3 % of the total. The ratio DDT/DDE was 0.0032 ± 0.0028. The mean PCB concentration was 12 ± 7 μg/g wet weight and 44 ± 78 μg/g lipid weight. When the 5 samples with lipid content < 20% were removed, the mean PCB concentration was 12 ± 7 μg/g wet weight and 24 ± 20 μg/g lipid weight.

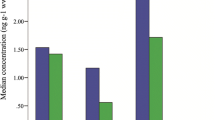

No effect of carcass condition on the tDDT and PCB concentrations in blubber lipid was detected (F = 2.577; df = 2,31; p = 0.092 for tDDT; F = 2.305; df = 2,31; p = 0.117 for PCBs). A trend towards a progressive decrease in tDDT and PCB concentrations from northern to southern California was noticed (F = 3.506; df = 2,22; p = 0.048 for tDDT; F = 3.012; df = 2,22; p = 0.070 for PCBs) (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences in tDDT and PCB concentrations among animals from different sex and age categories (F = 0.758; df = 4,22; p = 0.563 for tDDT; F = 0.861; df = 4,22; p = 0.503 for PCBs) (Fig. 2). Conversely, there was a negative relationship between blubber lipid content and tDDT and PCB concentrations (F = 6.780; df = 1,22; p = 0.016 for tDDT; F = 11.060; df = 1,22; p = 0.003 for PCBs).

Discussion

Lipid content

The mean lipid content in blubber was low relative to the value of 84–85% reported in apparently healthy sea lions [23]. The condition of the carcass might be responsible for these differences in blubber lipid content among individuals but no significant difference was reported in the lipid content of the blubber between fresh, moderately decomposed and advanced decomposed carcasses. Indeed, some of the extremely low lipid contents were from fresh carcasses. The low lipid content of several animals may have resulted from the mobilization of fat reserves from the blubber prior to death due to starvation or disease, as suggested by Kajiwara et al. [22].

There was a strong negative relationship between lipid content of the blubber and tDDT and PCB concentration in the blubber. This relationship was observed in a previous study on California sea lions [22], which reported that the highest concentrations of both tDDT and PCBs were found in individuals with the lowest blubber lipid content. Similarly, other studies of pinnipeds and cetacea report a negative relation between blubber thickness and concentrations of organochlorines [14, 24–26]. This negative relationship can be explained by the fact that fat-soluble contaminants such as tDDT and PCBs are less easily mobilized from the blubber than lipids during fasting and thus tend to accumulate in the remaining blubber layer [24, 27].

Sex and age categories

The usual pattern observed in marine mammals is an increase of fat-soluble contaminants such as PCBs and tDDT in the tissues of males and immature females, while in mature females, levels decrease or remain unchanged, as they excrete PCBs and tDDT through the fetus and nursing. As a consequence, males are generally more contaminated than females and juveniles [9, 10, 12–14]. This has not been documented specifically in California sea lions and their habits make it difficult to do so. Males migrate north of the area for half the year while lactating females stay in the Southern California Bight all year round in close proximity to the tDDT hotspot near Palos Verdes. Sample sizes in this study were insufficient to adequately test for sex and age differences. Moreover, the females collected in central California may have been non-lactating, not yet parous, or simply younger, having experienced fewer reproductive cycles. More data are needed to address changes in contamination levels as a function of sex or age.

Location

The pattern of contaminant levels as a function of the stranding location observed in the present study was somewhat unexpected. It may, however, be explained in part by the fact that individuals, males in particular, move long distances and feed on a variety of prey, that themselves move significantly. The principal prey of California sea lions are northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax), Pacific whiting (Merluccius productus), mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus), rockfish (Sebastes spp.), and market squid (Loligo opalescens) [28–30], highly mobile, vertically and horizontally migrating, schooling species that are widely dispersed on or near the coastal continental shelf with distributions that vary seasonally and annually [31, 32]. As a consequence, the concentrations reported here may not necessarily reflect the contamination levels of prey in the area where the sea lions stranded.

tDDT/PCB and DDT/DDE ratios

tDDT concentrations in California sea lions were approximately 3 times higher than PCB concentrations, a pattern characteristics of marine mammals from the California coast. This is in contrast to the North Atlantic, Arctic, Gulf of St Lawrence, Mediterranean sea, and the coast of Washington, where PCB concentrations in the blubber of marine mammals are usually as high or higher (up to 1 order of magnitude) than tDDT concentrations [3, 9, 10, 13, 33–41]. Only a few studies, such as those on the contamination of Baikal seal (Pusa sibirica), northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) and killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Oregon, report higher levels of tDDT than PCBs [3, 12, 42]. The scant information on marine mammals from the tropical and equatorial fringe of the Northern Hemisphere generally also report tDDT as the main pollutant, followed closely or equaled by PCBs [43]. Kajiwara et al. [22] observed higher levels of tDDT compared to PCB in the blubber and liver of California sea lions while they found the reverse in the livers of harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) in California. They concluded that California sea lions, stranded in central and northern California probably spent parts of the year feeding in the Southern California Bight while harbor seals, also stranded in central and northern California, remained at the same location throughout the year and thus received exposure only locally [22]. Sea otter (Enhydra lutris) tissues from California also showed higher levels of tDDT compared to PCBs, while in the tissues of the same species from Alaska, the reverse was reported [44, 45]. Thus, the tDDT/PCB ratio appears to be higher in California and may originate, at least partly, from the DDT hotspot in the Southern California Bight, the legacy of DDT production and byproduct dumping over 30 years ago.

The high proportion of DDE, a DDT metabolite, in tDDT is in the upper range of reports in the literature for other marine mammal species [22, 37, 39, 40, 43, 45–47]. A high proportion of DDE reflects the absence of recent DDT contamination. The ratio DDT/DDE in 2000 (0.0032) however is lower than in the studies of Le Boeuf and Bonnell [19] as well as Lieberg-Clark et al. [21] that reported ratios of 0.023 and 0.032, respectively. This suggests that the composition of tDDT contamination is still changing towards a lower amount of DDT. As the proportion of DDE seems to increase with age in adult males [10], differences between studies may vary in part with the number of older males in each sample.

Temporal trends

To better assess the decline in tDDT levels over the last 30 years and to avoid the potential confounding factor of sex, we compared males in this study with blubber lipid contents higher than 20% with a similar sample of males reported in previous studies [19, 21] (Fig. 3). Blubber tDDT levels were more than 90% lower in 2000 than in 1970. Even so, an accurate estimation of the rate of decrease is elusive because analytical methods for organochlorines have improved in accuracy over the last 30 years [43, 47]. Packed columns, commonly used before the 1980s, underestimated DDT concentrations by 30–40% [43]. In contrast, Addison and Stobo [47] mention DDT-group analyses that were internally consistent from the early 1970s to the early 1990s. In addition, a potential overestimation of tDDT levels due to their co-elution with some PCB congeners was noted for the California sea lion samples in the 1970s [25]. Nevertheless, the main interference would have been the co-elution of p,p'DDT with PCBs, which represents a small proportion of tDDT [[48] in [21]]. Thus, we conclude that the decline of tDDT during the last 30 years was over one order of magnitude.

tDDT levels in the blubber of male California sea lions stranded in California between 1970 and 2000. Mean values are presented. Blubber samples with a lipid content of less than 20% are excluded. Data are from 2000 (present study n = 20), as well as from 1990 (1988–1992, average = 1990 n = 7) [21] and 1970 (n = 20) [19]. Individual data and SD from the study of 1990 were not available.

The decrease in tDDT in California sea lions during the last 30 years, although impressive in magnitude, is in general accordance with declines in other marine mammals [43]. Moreover, although the mean level of tDDT is much lower in 2000 than in 1970, inter-individual variation remains high; several individuals in 2000 exhibited concentrations within the range of concentrations reported in 1970.

It is difficult to draw conclusions concerning the trends of PCBs during the last few decades. The studies in the 1970s reporting PCB concentrations in California sea lions dealt only with lactating females [23, 49]. Moreover, the techniques for analyzing PCBs in the 1970s (packed columns) overestimated the levels by about 50% [43]. PCB concentrations were also expressed as Aroclor mixture and not in a congener-specific approach [43, 47]. In general, a decrease in PCB levels in marine mammal tissues is often reported [43]. The magnitude of the drop seems to vary with time as well as with geographical areas. No systematic trends, or even increases in levels, are observed in some regions such as the Antarctic [43].

Inter-species differences and geographical trends

Despite the marked decline in tDDT in California sea lions over the last 3 decades, levels remain higher in this animal than in most other marine mammals, even when only samples with blubber lipid content >20% were taken into account. Mean tDDT concentrations in the blubber of California sea lions from the present study are higher (up to 2 orders of magnitude) than current levels reported in other marine mammal species, such as harbor seals, harp seals (Phoca groenlandica), grey seals (Halichoerus grypus), white whales (Delphinapterus leuca), fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus), bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) from other geographical areas [27, 38–40, 43, 47, 50]. Similarly, PCB levels also appear to be higher than in several other species and geographical areas, although the difference is more moderate. In general, marine mammals from the West Coast of North America display among the highest DDT and PCB loads observed [43].

California sea lions are among the most highly contaminated species along with northeastern Pacific killer whales, St. Lawrence beluga whales, Mediterranean striped dolphin (stenella coeruleoalba), and Mediterranean bottlenose dolphins [42, 43, 51, 52]. It is remarkable that California sea lions exhibit PCB levels that are of the same order of magnitude as those reported in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from Svalbard, which feed at a higher trophic level, while the tDDT concentrations in California sea lions are 2 to 3 orders of magnitude higher than those of polar bears [36]. Several factors such as sex, age, feeding habits, physiological status (sick, lactating, starving) and analytical techniques exert an influence on organochlorine concentrations and might be partially responsible for the difference between species and geographical areas.

Toxicological effects

Despite relatively high concentrations of tDDT and PCBs, there is no evidence that population growth or the health of individual California sea lions have been compromised. The population has increased throughout the century, including the period when DDT was being manufactured, used, and its wastes discharged off southern California. Few attempts to measure toxicological endpoints in California sea lions have been made [23, 49]. The increase in their numbers suggests a healthy population but does not necessarily mean that the contamination by these organochlorines has not exerted an effect on individuals. The concentrations of PCBs reported in the present study are above the 17 mg/kg lipid weight threshold that elicits effects at physiological levels on endocrine and immune systems [53, 54]. DDT and its metabolites have been shown to be hormone-disrupters, and to induce estrogenic as well as anti-androgenic effects on several species [55–57]. Premature pupping in the early seventies was attributed to the contamination by tDDT [23, 49], however, the role of DDT and its metabolites in this reproductive failure was not ascertained and remains unclear [25, 58]. A real cause-effect relationship between contaminant concentrations and factors of the immune or endocrine system is difficult to determine due to confounding factors. Nevertheless, concentrations reported here are sufficiently high to encourage continued investigation.

Conclusions

tDDT concentrations have decreased significantly in blubber tissues of California sea lions during the last three decades. Systematic changes in PCB levels are difficult to discern, due to a paucity of data and analytical differences over the years.

We found an unexpected trend towards an increase in the contamination levels from southern to northern California. This does not necessarily mean that the northern part of California is more polluted than the southern part, as California sea lions move about widely and feed on mobile prey. The high ratio of tDDT to PCB concentrations in California sea lions is in part derived from the geographical area they inhabit, where higher tDDT concentrations than PCBs are reported, as compared to other parts of the world. No sex or age difference in contamination levels were found but further study and a larger sample size is needed to confirm the lack of a difference.

Despite the noticeable drop of DDT in California sea lion blubber, concentrations remain high compared to other marine mammals around the world. PCB concentrations are as high or higher than those known to induce effects at a physiological level. This is a cause for concern for the animals as well as for humans that feed on contaminated fishes in the area.

Methods

Sample collection

Blubber tissue samples were collected from 36 dead California sea lions stranded on islands and the coast of California between April and November 2000 (Table 1). The location, sex, standard length, estimated age category, and condition of the stranded pinnipeds were recorded. The condition of carcasses was characterized as fresh, moderately decomposed or less than two weeks dead, and in advanced decomposition or estimated to be more than two weeks dead. Animals from southern California were found on the Channel Islands, those from central California at Año Nuevo Island, and those from northern California at Marin, Mendocino and Humboldt counties. A tissue sample weighing approximately 150 grams was excised from the medial ventrum region at the level of the axilla, from outer skin to muscle. Samples were deposited in clean jars and refrigerated until organochlorine analysis was conducted.

Chemical analyses

The tDDT and PCB analyses were conducted as described elsewhere [22]. The PCB standard used for quantification was an equivalent mixture of Kanechlor preparations (KC-300, KC-400, KC-500, KC-600). Concentrations of total PCBs were based on the sum 84 peaks, representing 117 major congeners. These congeners represent all those that could be found in technical PCB preparations and in the environment.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the GLM procedure (SYSTAT 10.0 windows version). In order to normalize the data, we took the square roots of tDDT and PCB concentrations in blubber lipids. Two outliers (individuals C110400–06 and C110400–07, Table 1) were removed from the data analysis because of their extremely high PCB and tDDT levels (Table 1) which were far outside the range of the whole data set.

The effects of carcass condition (fresh, moderately decomposed, advanced decomposed) on blubber lipid content as well as on the PCB or tDDT levels in blubber lipids were first examined using a one-way fixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) since decomposition of the carcass and a resulting change in blubber lipid content can affect PCB or DDT concentration. However, carcass condition had no significant effect on either blubber lipid content or PCB/tDDT concentrations in blubber lipids (see Results section). For this reason and because of the relatively imprecise character of this factor, it was removed from further analyses.

The effect of blubber lipid content of the blubber (lipid), sex and age category (sex-age category), and the location where the sample was collected (location) on tDDT or PCB concentrations in blubber lipids were examined using a three-way fixed-model analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with lipid as a continuous variable and sex-age category and location as categorical variables. In a preliminary analysis, we tested the homogeneity of slopes. As the interactions with the continuous variable (lipid) were non-significant in both PCB and tDDT analyses (p > 0.05), we assumed parallelism and pooled these interactions with the model mean square error. The effects of lipid, sex-age category and location were then re-tested under the reduced linear model (see Results section).

References

Tanabe S, Tatsukawa R, Tanaka H, Maruyama K, Miyazaki N, Fujiyama T: Distribution and total burdens of chlorinated hydrocarbons in bodies of striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba). Agric Biol Chem. 1981, 45 (11): 2569-2578.

Muir DCG, Segstro MD, Hobson KA, Ford CA, Steward REA: Can seal eating explain elevated levels of PCBs and organochlorine pesticides in walrus blubber from Eastern Hudson Bay (Canada)?. Environ Pollut. 1995, 90 (3): 335-348. 10.1016/0269-7491(95)00019-N.

Mossner S, Ballschmiter K: Marine mammals as global pollution indicators for organochlorines. Chemosphere. 1997, 34 (5–7): 1285-1296. 10.1016/S0045-6535(97)00426-8.

Bard SM: Global transport of anthropogenic contaminants and the consequences for the Arctic marine ecosystem. Mar Pollut Bull. 1999, 38 (5): 356-379. 10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00041-7.

Mate BR: Annual migrations of the sea lions Eumetopias jubatus and Zalophus californianus along the Oregon coast. P-v Reun Cons Int Explor Mer. 1975, 169: 455-461.

Peterson RS, Bartholomew GA: The Natural History and Behavior of the California Sea Lion. The American Society of Mammalogists. 1967

Melin SR, DeLong RL, Thomason JR, VanBlaricom GR: Attendance patterns of California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) females and pups during the non-breeding season at San Miguel Island. Mar Mammal Sci. 2000, V16 (N1): 169-185.

Addison RF, Brodie PF: Organochlorine residues in maternal blubber, milk, and pup blubber from grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) from Sable Island, Nova Scotia. J Fish Res Board Can. 1977, 34: 937-941.

Aguilar A, Borrell A: Reproductive transfer and variation of body load of organochlorine pollutants with age in fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus). Arch Environ Toxicol. 1994, 27: 546-554.

Borrell A, Bloch D, Desportes G: Age trends and reproductive transfer of organochlorine compounds in long-finned pilot whales from the Faroe Islands. Environ Pollut. 1995, 88: 283-292. 10.1016/0269-7491(95)93441-2.

Beckmen KB, Ylitalo GM, Towell RG, Krahn MM, O'Hara TM, Blake JE: Factors affecting organochlorine contaminant concentrations in milk and blood of northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) dams and pups from St George Island, Alaska. Sci Total Environ. 1999, 23: 183-200. 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00094-7.

Nakata H, Tanabe S, Tatsukawa R, Amano M, Miyazaki N, Petrov EA: Persistent Organochlorine residues and their accumulation kinetics in Baikal seal (Phoca sibirica) from Lake Baikal, Russia. Environ Sci Technol. 1995, 29: 2877-2885.

Corsolini S, Focardi S, Kannan K, Tanabe S, Borrell A, Tatsukawa R: Congener profile and toxicity assessment of polychlorinated biphenyls in dolphins, sharks and tuna collected from Italian coastal waters. Mar Environ Res. 1995, 40: 33-53. 10.1016/0141-1136(94)00003-8.

Aguilar A, Borrell B, Pastor T: Biological factors affecting variability of persistent pollutant levels in cetaceans. J Cetacean Res Manage. 1999, 1: 83-116.

Safe SH: Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): environmental impact, biochemical and toxic responses, and implications for risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1994, 24: 87-149.

Helle E, Olsson M, Jensen S: DDT and PCB levels and the reproduction in ringed seals from the Bothnian Bay. Ambio. 1976, 5: 188-189.

Martineau D, Lagacé A, Béland P, Higgins R, Armstrong D, Shugart LR: Pathology of stranded beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) from the St Lawrence estuary, Quebec, Canada. J Comp Path. 1988, 98: 287-310.

Aguilar A, Borrell A: Abnormally high polychlorinated biphenyl levels in striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) affected by the 1990–1992 Mediterranean epizootic. Sci Total Environ. 1994, 154: 237-247. 10.1016/0048-9697(94)90091-4.

Le Boeuf BJ, Bonnell ML: DDT in California sea lions. Nature. 1971, 234: 108-110.

Zeng EY, Venkatesan MI: Dispersion of sediment DDTs in the coastal ocean off southern California. Sci Total Environ. 1999, 229: 195-208. 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00064-9.

Lieberg-Clark P, Bacon CE, Burns SA, Jarman WM, Le Boeuf BJ: DDT in California sea-lions: A follow-up study after twenty years. Mar Pollut Bull. 1995, 30: 744-745. 10.1016/0025-326X(95)00156-H.

Kajiwara N, Kannan K, Muraoka M, Watanabe M, Takahashi S, Gulland F, Olsen H, Blankenship AL, Jones PD, Tanabe S, Giesy JP: Organochlorine pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls, and butyltin compounds in blubber and livers of stranded California sea lions, elephant seals, and harbor seals from coastal California, USA. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2001, 41: 90-99. 10.1007/s002440010224.

Gilmartin WG, DeLong RL, Smith AW, Sweeny JC, De Lappe BW, Risebrough RW, Griner LA, Dailey MD, Peakall DB: Premature parturition in the California sea lion. J Wild Dis. 1976, 12: 104-114.

Kannan K, Tanabe S, Borrell A, Aguilar A, Focardi S, Tatsukawa R: Isomer-specific analysis and toxic evaluation of polychlorinated biphenyls in striped dolphins affected by an epizootic in the western Mediterranean Sea. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1993, 25: 227-233.

Addison RF: Organochlorine and marine mammal reproduction. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1989, 46: 360-368.

Wolkers J, Burkow IC, Lydersen C, Dahle S, Monshouwer M, Witkamp RF: Congener specific PCB and polychlorinated camphene (toxaphene) levels in Svalbard ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in relation to sex, age, condition and cytochrone P450 enzyme activity. Sci Total Environ. 1998, 216: 1-11. 10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00131-4.

Debier C: A study of the dynamics of vitamin A, vitamin E and PCBs in seals during lactation. PhD thesis, University of Louvain, Belgium. 2001

Antonelis GA, Fiscus CH, DeLong RL: Spring and summer prey of California sea lions, Zalophus californianus, at San Miguel Island, California, 1978–79. Fish Bull. 1984, 82: 67-76.

Lowry MS, Oliver CW, Macky C, Wexler JB: Food habits of California sea lions Zalophus californianus at San Clemente Island, California, 1981–86. Fish Bull. 1990, 88: 509-521.

Lowry MS, Stewart BS, Heath CB, Yochem PK, Francis JM: Seasonal and annual variability in the diet of California sea lions Zalophus californianus at San Nicolas Island, California, 1981–86. Fish Bull. 1991, 89: 331-336.

Vaughan DL, Recksiek CW: An acoustic investigation of market squid, Loligo opalescens. In: Biological, oceanographic, and acoustic aspects of the market squid, Loligo opalescens, Berry. Edited by: Recksiek CW, Frey HW. 1978, Calif Dep Fish & Game Bull, 135-147.

Dark TA, Nelson MO, Traynor JJ, Nunnallee EP: The distribution, abundance, and biological characteristics of Pacific whiting, Merluccius productus, in California – British Columbia region during July – September 1977. Mar Fish Rev. 1980, 42: 17-33.

Hong CS, Calambokidis J, Bush B, Steiger GH, Shaw S: Polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticide in harbour seal pups from the inland waters of Washington State. Environ Sci Technol. 1996, 30: 837-844. 10.1021/es950270v.

Jenssen BM, Skaare JU, Ekker M, Vongraven D, Lorentsen SH: Organochlorine compounds in blubber, liver and brain in neonatal grey seal pups. Chemosphere. 1996, 32: 2115-2125. 10.1016/0045-6535(96)00130-0.

Muir DCG, Koczanski K, Rosenberg B, Béland P: Persistent organochlorines in beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) from the St Lawrence river estuary-II Temporal trends, 1982–1994. Environ Pollut. 1996, 93: 235-245. 10.1016/0269-7491(96)00008-5.

Bernhoft A, Wiig Ø, Skaare JU: Organochlorines in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) at Svalbard. Environ Pollut. 1997, 95: 159-175. 10.1016/S0269-7491(96)00122-4.

Espeland O, Kleivane L, Haugen S, Skaare JU: Organochlorines in mother and pup pairs in two Artic seals species: harp seal (Phoca groenlandica) and hooded seal (Cystophora cristata). Mar Environ Res. 1997, 44: 315-330. 10.1016/S0141-1136(97)00010-X.

Bernt KE, Hammill MO, Lebeuf M, Kovacs KM: Levels and patterns of PCBs and OC pesticides in harbour and grey seals from the St Lawrence Estuary, Canada. Sci Total Environ. 1999, 243/244: 243-262. 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00400-3.

Kleivane L, Severinsen T, Skaare JU: Biological transport and mammal to mammal transfer of organochlorines in Arctic fauna. Mar Environ Res. 2000, 49: 343-357. 10.1016/S0141-1136(99)00079-3.

Andersen G, Kovacs KM, Lydersen C, Skaare JU, Gjertz I, Jenssen BM: Concentrations and patterns of organochlorine contaminants in white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) from Svalbard, Norway. Sci Total Environ. 2001, 264: 267-281. 10.1016/S0048-9697(00)00765-8.

Troisi GM, Mason CF: PCB-associated alteration of hepatic steroid metabolism in Harbour Seals (Phoca vitulina). J Toxicol Environ Health Part A. 2001, 61: 649-655. 10.1080/00984100050195134.

Hayteas DL, Duffield DA: High levels of PCB and p,p'-DDE found in the blubber of killer whales (Orcinus orca). Mar Pollut Bull. 2000, 40: 558-561.

Aguilar A, Borrell A, Reijnders PJH: Geographical and temporal variation in levels of organochlorine contaminants in marine mammals. Mar Environ Res. 2002, 53: 425-452. 10.1016/S0141-1136(01)00128-3.

Estes JA, Bacon CE, Jarman WM, Norstrom RJ, Anthony RG, Miles AK: Organochlorines in sea otters and bald eagles from Aleutian Archipelago. Mar Pollut Bull. 1997, 34 (6): 486-490. 10.1016/S0025-326X(96)00178-6.

Nakata H, Kannan K, Jing L, Thomas N, Tanabe S, Giesy JP: Accumulation pattern of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis) found stranded along coastal California, USA. Environ Pollut. 1998, 103: 45-53. 10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00136-5.

Tanabe S, Sung JK, Choi DY, Baba N, Kiyota M, Yoshida K, Tatsukawa R: Persistent organochlorine residues in Northern fur seal from the Pacific coast of Japan since 1971. Environ Pollut. 1994, 85: 305-314. 10.1016/0269-7491(94)90052-3.

Addison RF, Stobo WT: Trends in organochlorine residue concentrations and burdens in grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) from Sable Is, NS, Canada, between 1974 and 1994. Environ Pollut. 2001, 112: 505-513. 10.1016/S0269-7491(00)00129-9.

Risebrough RW: Chlorinated hydrocarbons in marine ecosystems. In: Chemical fallout: Current Research on Persistent Pesticides. Edited by: Miller MW, Berg GC. 1969, Charles C Thomas, Springfield, IL

DeLong RL, Gilmartin WG, Simpson JG: Premature births in California sea lions: association with high organochlorine pollutant residue levels. Science. 1973, 181: 1168-1170.

Severinsen T, Skaare JU, Lydersen C: Spatial distribution of persistent organochlorines in ringed seal (Phoca hispida) blubber. Mar Environ Res. 2000, 49: 291-302. 10.1016/S0141-1136(99)00078-1.

Muir DCG, Ford CA, Rosenberg B, Norstrom RJ, Simon M, Beland P: Persistent organochlorines in beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) from the St Lawrence River estuary. I. Concentrations and patterns of specific PCBs, chlorinated pesticides and polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans. Environ Pollut. 1996, 93: 219-234. 10.1016/0269-7491(96)00006-1.

Ross PS, Ellis GM, Ikonomou MG, Barrett-Lennard LG, Addison RF: High PCB concentrations in free-ranging Pacific Killer whales, Orcinus orca: Effects of age, sex and dietary preference. Mar Pollut Bull. 2000, 40: 504-515. 10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00233-7.

Ross PS, De Swart RL, Addison R, Van Loveren H, Vos J, Osterhaus A: Contaminant-induced immunotoxicity in harbour seals: wildlife at risk?. Toxicology. 1996, 112: 157-169. 10.1016/0300-483X(96)03396-3.

Kannan K, Blankenship AL, Jones PD, Giesy JP: Toxicity reference values for the toxic effects of polychlorinated biphenyls to aquatic mammals. Hum Ecol Risk Assess. 2000, 6: 181-201.

Fry DM: Reproductive effects in birds exposed to pesticides and industrial chemicals. Environ Health Perspect. 1995, 103 (Suppl 7): 165-171.

Greenlee AR, Quail CA, Berg RL: Developmental alterations in murine embryos exposed in vitro to an estrogenic pesticide, o,p'-DDT. Reproductive Toxicol. 1999, 13: 555-565. 10.1016/S0890-6238(99)00051-9.

Colborn T, vom Saal FS, Soto AM: Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environ Health Perspect. 1993, 101: 378-384.

O'Shea TJ, Brownell RL: California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) populations and DDT contamination. Mar Pollut Bull. 1998, 36: 159-164. 10.1016/S0025-326X(97)00102-1.

Acknowledgements

We thank Steve Hansen for advice and helpful discussion, Scott Davis, Richard Gantt, David Larsen and Mark Lowry for assistance in tissue collection, Matthew Edwards and Peter Raimondi for valuable suggestions on data analysis. CD was supported by a Fellowship from the Belgian American Educational Foundation (BAEF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contribution

BJL conceived the study, directed collection of samples, conducted data analyses and wrote the manuscript. JG and KK provided comments on manuscript drafts. JG and ST funded chemical analyses and conducted some analyses. NK and KK conducted most of the chemical analyses. CD provided comments on the final draft from the perspective of ecotoxicology, performed statistical analyses, and helped draft the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Le Boeuf, B.J., Giesy, J.P., Kannan, K. et al. Organochloride pesticides in California sea lions revisited. BMC Ecol 2, 11 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6785-2-11

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6785-2-11