Abstract

Background

Tumor size is a critical variable in staging for renal cell carcinoma. Clinicians rely on radiological estimates of pathological tumor size to guide patient counseling regarding prognosis, choice of treatment strategy and entry into clinical trials. If there is a discrepancy between radiological and pathological measurements of renal tumor size, this could have implications for clinical practice. Our study aimed to compare the radiological size of solid renal tumors on computed tomography (CT) to the pathological size in an Australian population.

Methods

We identified 157 patients in the Westmead Renal Tumor Database, for whom data was available for both radiological tumor size on CT and pathological tumor size. The paired Student's t-test was used to compare the mean radiological tumor size and the mean pathological tumor size. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. We also identified all cases in which post-operative down-staging or up-staging occurred due to discrepancy between radiological and pathological tumor sizes. Additionally, we examined the relationship between Fuhrman grade and radiological tumor size and pathological T stage.

Results

Overall, the mean radiological tumor size on CT was 58.3 mm and the mean pathological size was 55.2 mm. On average, CT overestimated pathological size by 3.1 mm (P = 0.012). CT overestimated pathological tumor size in 92 (58.6%) patients, underestimated in 44 (28.0%) patients and equaled pathological size in 21 (31.4%) patients. Among the 122 patients with pT1 or pT2 tumors, there was a discrepancy between clinical and pathological staging in 35 (29%) patients. Of these, 21 (17%) patients were down-staged post-operatively and 14 (11.5%) were up-staged. Fuhrman grade correlated positively with radiological tumor size (P = 0.039) and pathological tumor stage (P = 0.003).

Conclusions

There was a statistically significant but small difference (3.1 mm) between mean radiological and mean pathological tumor size, but this is of uncertain clinical significance. For some patients, the difference leads to a discrepancy between clinical and pathological staging, which may have implications for pre-operative patient counseling regarding prognosis and management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tumor size is an important prognostic indicator for renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and is thus a critical variable in staging systems and a key factor when deciding upon treatment strategy.

The 2009 TNM staging system for RCC stratifies tumors limited to the kidney by their size alone (T1a ≤4 cm; T1b > 4 cm but ≤7 cm; T2a > 7 cm but ≤10 cm; T2b > 10 cm)[1]. Available prognostic nomograms also incorporate tumor size[2–5].

Renal tumor size also guides clinicians in recommending radical nephrectomy (RN), partial nephrectomy (PN), ablative techniques or active surveillance as the management of choice. PN is the standard approach for T1a (≤4 cm) renal tumors, achieving equivalent oncological efficacy to RN[6], while preserving renal function[7] and protecting from non-cancer related mortality[8, 9]. Several studies support PN for all amenable T1b tumors (> 4 cm but ≤7 cm) [10–14]. The growing acceptance of PN as an option for T1b tumors is reflected in current American and European guidelines[15, 16]. RN remains the therapy of choice for T2 tumors (> 7 cm) [16, 17]. Although recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of PN for carefully selected patients with T2 tumors in experienced centers[18, 19], it is uncertain whether these results can be extrapolated to all institutions. For high-risk surgical candidates with small renal tumors, there is intermediate-term data to support minimally invasive ablative techniques such as cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [20]. There is a relationship between tumor size and local recurrence after ablation[20], and a tumor size threshold of 3.5 cm has been proposed for such techniques[17]. In patients with limited life expectancy, active surveillance of small renal masses has been advocated as a viable option, provided that tumor size is less than 3 cm[21].

Most studies report patient outcomes following surgical intervention for RCC according to the pathological size of the tumor, rather than the radiological size on CT[2–5, 22, 23]. Indeed, the studies that have defined a tumor size threshold for partial nephrectomy are all based on pathological size[6, 7, 10–14].

Preoperatively, clinicians must rely on radiological estimates of pathological tumor size to guide patient counseling regarding prognosis and management. For example, at institutions employing a size threshold for PN, patients will be offered or denied PN based on tumor size on CT. If there is a discrepancy between radiological size on CT and pathological size, this may have implications for clinical practice.

For patients undergoing ablative techniques, pathological tumor size cannot be determined. Therefore, studies report the outcome of ablative techniques according to radiological tumor size[20]. If a discrepancy between radiological and pathological tumor size exists, it may be difficult to meaningfully compare these studies with the established evidence for nephrectomy, which is reported according to pathological size.

A number of studies have examined the relationship between CT size and pathological size of renal tumors[24–36]. Most of these studies found that, on average, CT overestimated pathological tumor size, although this reached statistical significance in only three studies[28, 33, 35]. Authors have disagreed on the clinical significance of these findings. Only two of these studies comprehensively reported instances in which disagreement between CT and pathological size led to discordance between clinical and pathological stage[26, 30]. To our knowledge, there has been no such study performed on an Australian population. A recent study has demonstrated different trends in stage migration in an Australian RCC cohort compared with populations in the USA[37]. Therefore, international findings are not necessarily applicable to the Australian population and there is a need for Australian data to be reported.

The aim of our study was to compare the radiological size of RCC on CT to the pathological size in a contemporary Australian population. We also aimed to identify patients who were up-staged or down-staged due to discrepancy between CT and pathological size.

Methods

The Westmead Renal Tumor Database contains 547 patients whose tumors were removed by radical or partial nephrectomy from 1994 to 2007. Data collection and analysis was approved by the hospital ethics committee and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

We retrospectively reviewed the database and identified 157 patients for whom accurate data was available for both radiological and pathological tumor size. Radiological tumor size was defined as the largest transverse diameter in the axial plane on CT scan, as measured by the reporting radiologist. The CT protocol entailed pre-contrast images and images in the arterial, corticomedullary (venous) and excretory phases. Tumor size was measured in the phase in which the tumor margins were most obvious. Coronal and sagittal reconstruction images were available, but the radiological tumor size was always measured in the axial plane. Pathological tumor size was defined as the largest transverse diameter, as measured by the pathologist at examination of the surgical specimen prior to formalin fixation. There were 4 patients with multifocal tumors. For these patients, we included the data for their largest tumor in our analysis. According to radiological size, tumors were grouped by 1 cm size intervals and by clinically relevant size intervals (≤4 cm; >4 cm but ≤7 cm; >7 cm but ≤10 cm; >10 cm).

We extracted demographic data for all patients from the database, including age, sex, year of operation, type of procedure (open or laparoscopic, radical or partial nephrectomy), tumor histology (conventional, papillary, chromophobe, other), Fuhrman grade, and clinical and pathological tumor stage (according to 2009 TNM staging system).

The paired Student's t-test was used to compare the mean radiological tumor size and the mean pathological tumor size. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Data analysis was performed using SPSS, version 15.0. We also compared mean radiological and mean pathological size for tumors grouped by histological subtype, by type of procedure, by 1 cm size intervals and by clinically relevant size intervals (≤4 cm; >4 cm but ≤7 cm; >7 cm but ≤10 cm; >10 cm).

For patients with pT1 and pT2 tumors, the radiological and pathological tumor sizes were compared to identify all cases of post-operative down-staging or up-staging. We calculated the number and percentage of patients for whom a difference between radiological and pathological tumor sizes accounted for discrepancy between clinical and pathological tumor stage.

We also examined the relationship between Fuhrman grade and CT tumor size (grouped into clinically relevant size intervals) and pathological T stage using a chi-square test. Of our cohort of 157 patients, 7 were excluded from this analysis because they did not have a Fuhrman grade recorded in the database. For the analysis we grouped tumors into low-grade (Fuhrman 1 or 2) and high-grade (Fuhrman 3 or 4).

Results

A total of 157 patients were identified, among whom there were 51 (32.5%) women and 106 men (67.5%). The mean (range) patient age was 63.3 (34-100) years. The patients underwent surgery between 1998 and 2007. There were 18 (11.5%) patients treated with partial nephrectomy (10 laparoscopic and 8 open procedures), and 139 (88.5%) treated with radical nephrectomy (100 laparoscopic and 39 open). The histological tumor subtype was conventional in 126 (80.3%) patients, papillary in 16 (10.2%), chromophobe in 11 (7.0%) and other in 4 (2.5%). The pathological tumor stage (according to the 2009 TNM staging system) was T1a in 58 (36.9%) patients, T1b in 41 (26.1%), T2a in 18 (11.5%), T2b in 5 (3.2%), T3a in 30 (19.1%), T3b in 2 (1.3%), T3c in 2 (1.3%) and T4 in 1 (0.6%). Demographic data for our study population is summarized in Table 1.

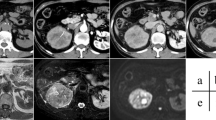

A scatter plot of pathological tumor size against radiological tumor size is shown in Figure 1. Overall, the mean radiological tumor size on CT was 58.3 mm (SD 29.2 mm) and the mean pathological size was 55.2 mm (SD 30.5 mm). On average, CT overestimated pathological size by 3.1 mm (95% CI: 0.7 to 5.5 mm, P = 0.012). CT overestimated pathological tumor size in 92 (58.6%) patients, underestimated in 44 (28.0%) patients and equaled pathological size in 21 (31.4%) patients.

Among the 122 patients with pT1 or pT2 tumors, there was a discrepancy between clinical and pathological staging in 35 (29%) patients. Of these, 21 (17%) patients were down-staged post-operatively and 14 (11.5%) were up-staged. This data is summarized in Table 2.

Table 3 shows the mean radiological and pathological tumor sizes divided into 10 mm size intervals by radiological size. Mean radiological size was greater than mean pathological size for all size intervals, except for the 50 - 59 mm and 70 - 79 mm categories. This only reached statistical significance for tumors in the 80 - 89 mm category, for which mean radiological size was 13 mm larger than mean pathological size (95% CI: 1.26 to 24.74 mm, P = 0.034).

Table 4 shows the mean radiological and pathological tumor sizes separated into clinically relevant size intervals, corresponding to T1a (≤4 cm), T1b (>4 cm but ≤7 cm), T2a (>7 cm but ≤10 cm) and T2b (>10 cm) stages. For all three groups, mean radiological size was greater than mean pathological size but the difference did not achieve statistical significance.

Table 5 shows the mean radiological and pathological tumor sizes for the different histological sub-types. For conventional RCC, CT overestimated pathological size by an average of 3.8 mm (95% CI 1.25 to 6.39 mm, P = 0.004). There was no statistically significant difference for the other histological subtypes.

Table 6 shows the mean radiological and pathological tumor sizes stratified by type of procedure. For tumors removed by radical nephrectomy, the mean radiological size was 3.4 mm larger than the mean pathological size (95% CI: 0.71 to 6.02 mm, P = 0.013). There was no statistically significant difference detected for tumors removed by partial nephrectomy.

Table 7 shows radiological tumor size (grouped into clinically relevant size intervals) distributed according to Fuhrman grade. High-grade disease (Fuhrman 3 or 4) was more common in larger tumors (≤4 cm vs >4 cm but ≤7 cm vs >7 cm; P = 0.039). The prevalence of high-grade disease was 24.5%, 31.1% and 50.0% for tumors ≤4 cm, >4 cm but ≤7 cm, >7 cm respectively. Table 8 shows pathological T stage (grouped into T1a, T1b and ≥ T2) distributed according to Fuhrman grade. There was a statistically significant positive correlation between Fuhrman grade and tumor stage (P = 0.003).

Discussion

Tumor size is an important prognostic indicator for RCC. Outcome of nephrectomy has been studied according to pathological tumor size. Pre-operatively, we must rely upon CT estimates of pathological tumor size to guide counseling regarding prognosis and choice of treatment modality. Furthermore, ablative techniques for renal tumors do not provide specimens for pathological assessment of tumor size. When comparing emerging ablative techniques to the benchmark of nephrectomy, we are comparing data based on pathological tumor size to data based on CT size. Therefore, it is important to understand the relationship between radiological tumor size and pathological tumor size, and to understand how any difference between the two measurements affects the accuracy of clinical staging.

Our study of a contemporary Australian cohort found that overall CT overestimated pathological tumor size by a statistically significant but small amount (3.1 mm). This observation is consistent with the findings of previous studies. The findings of recent papers comparing mean radiological and mean pathological renal tumors sizes are summarized in Table 9. Kurta et al[28] reported on the largest series (N = 521), and found that mean radiological tumor size was larger than mean pathological tumor size by 1 mm. Similarly, CT was found to overestimate pathological tumor size overall by 6.3 mm in a study by Herr[35], and by 10.0 mm in a paper by Irani et al[33]. Schlomer et al[31] found no statistically significant difference overall, but found that CT overestimated pathological size for pT1a tumors by 3.9 mm and for lesions 40 to 50 mm by 8.7 mm. Similarly, Lee et al[24] found a statistically significant overestimation of pathological tumor size by CT for tumors in the 40 to 50 mm range only, by an average of 2 mm. Choi et al[25] found that CT tumor size was on average larger than pathological size for smaller tumors only (<6 cm or T1). In several other series, mean radiological tumor size was greater than mean pathological size, but the difference did not reach statistical significance[27, 29, 30, 32, 34, 36]. Only one study reported an underestimation of pathological tumor size by CT overall, and this achieved statistical significance for T1a tumors only[26].

Analysis by histological subtype in our series showed a statistically significant difference for conventional RCC only, with CT overestimating pathological size by an average of 3.8 mm. The small number of papillary (N = 18) and chromophobe (N = 11) tumors included in our study meant we were unlikely to detect a statistically significant difference. Several studies have shown that CT size is greater than pathological size on average for conventional RCC, and smaller than pathological size on average for papillary RCC[24, 28, 32]. Kurta et al[28] found that CT overestimated pathological tumor size by 2.3 mm for conventional RCC and underestimated pathological tumor size by 5.4 mm for papillary RCC. Similarly, Lee et al[24] found that CT size was 1.4 mm greater than pathological size on average for conventional RCC, and 5.3 mm smaller for papillary RCC. In contrast, Herr[34] found that pathological size was overestimated on CT for all histological subtypes, and that the overestimation was significantly greater for conventional RCC compared to other subtypes (9.7 mm versus 3.9 mm). Similarly, Choi et al[25] demonstrated that mean radiological tumor size was larger than mean pathological tumor size for all histological subtypes, but there was no significant difference between groups.

The discrepancy between clinical and pathological tumor size has been attributed to decreased tumor vascularity after excision, leading to a diminished size post-operatively[34]. This effect is probably more pronounced for clear cell carcinomas because they typically have a richer vascular network than other histological subtypes. Yaycioglu et al[32] postulated that certain radiological and pathological features might influence the accuracy of tumor size measurement by CT. These features included: concomitant pyelonephritis, presence of hemorrhage or hematoma, cystic tumor or adjacent cysts, dilatation of adjacent renal calyces and invasion of the collecting system. The same study found that tumor invasion of perinephric tissues impacted upon the accuracy of CT. For these tumors, CT more frequently underestimated pathological size when compared to tumors confined to the kidney. Ates et al[26] demonstrated less accurate CT measurement of tumor size for locally invasive tumors. It may be more difficult to delineate the radiographic margin of invasive tumors on CT, leading to disagreement between radiological and pathological tumor sizes. Ates et al[26] also found more accurate measurement of tumors size on CT for exophytic lesions. Herr[35] found that CT more closely approximated pathological tumor size for upper pole tumors, but other studies have failed to confirm this finding[24, 32, 33]. Additionally, in our study the radiological and pathological tumor sizes were not necessarily measured in the same geometric plane and this could contribute to the discrepancy between the two measurements. The largest tumor diameter on CT was measured in the axial plane, and this did not always correspond to the plane in which the largest diameter was measured at pathological exam. Formalin fixation is known to cause tumor shrinkage[38], but in our series the pathological specimens were examined prior to fixation.

Inaccurate CT estimation of pathological tumor size led to discordance between clinical and pathological stage in over one quarter of tumors limited to the kidney in our study (pT1, pT2). Of these, 21 (17%) patients were down-staged and 14 (11.5%) up-staged post-operatively. There is limited published data on the impact that disagreement between radiological and pathological tumor sizes may have on staging discrepancies. Kanofsky et al[30] reported on a series of 198 renal cell carcinomas and identified 21 patients for whom disagreement between CT and pathological tumor size led to discrepancy between clinical and pathological tumor stage. Of these, 15 patients were down-staged and 6 up-staged post-operatively. Ates et al[26] found that differences between radiological and pathological measurements led to staging discrepancies in 19 of 86 patients, with 6 patients being down-staged and 13 patients being up-staged post-operatively. Kurta et al[28] and Lee et al[24] only reported cases of post-operative down-staging. Kurta et al demonstrated that among 258 patients with CT tumor size greater than 4 cm, 30 (11.6%) had a pathological size of less than 4 cm. Among 92 patients with CT tumor size greater than 7 cm, 7 (7.6%) had a pathological size of less than 7 cm. Lee et al demonstrated similar results. Of the 141 patients with CT tumor size between 4 cm and 7 cm, 17 (12.1%) had a pathological size less than 4 cm. Of the 87 patients with CT tumor size greater than 7 cm, 8 (9.2%) had a pathological size of less than 7 cm.

For these patients, pre-operative counseling regarding prognosis and management would have been based on a clinical tumor stage that was ultimately down-staged or up-staged based on pathological tumor size. Thus, although the magnitude of the mean difference between radiological and pathological tumor sizes is only 3.1 mm, there are cases where the discrepancy may impact upon clinical management.

Authors disagree about the clinical implications of the small but statistically significant difference between CT and pathological tumor size. Some studies conclude that CT adequately approximates pathological tumor size[24, 26, 32, 34], and that any discrepancy between the two measurements has minimal impact on patient management[28]. Other authors point out that overestimation of pathological size on CT could affect selection of patients for elective PN[29, 31, 33, 34]. PN is the standard of care for T1a tumors (≤4 cm) [17]. Mistry et al[29] report that 5 (5%) of their patients who were not offered elective PN based on a CT tumor size > 40 mm, had a pathological size ≤4 cm. Likewise, 3 patients out of 100 included in the study by Irani et al[33] were ineligible for elective PN based on CT size > 40 mm, but had a pathological size ≤4 cm. However, with the growing impetus to use PN for all amenable T1 tumors[15, 16], tumor size is becoming less important for determining patient eligibility for PN. Several authors argue that the decision to perform elective PN should be based on technical feasibility and patient preference rather than a rigid tumor size cut-off[12, 13, 18, 19, 39].

The discrepancy between radiological and pathological tumor size could have implications for the use of ablative techniques and active surveillance for RCC. These approaches produce no specimen for pathological assessment, and so we must rely upon CT estimates of tumor size to guide management. Decision-making under these circumstances is aided by the small number of studies that report tumor prognosis according to radiological tumor size. Kanao et al[40] have recently developed a preoperative prognostic nomogram based on clinical staging to predict survival after nephrectomy. Raj et al[41] have also developed a preoperative nomogram to predict the development of metastases after nephrectomy. Such prognostic data based on clinical information can be used as a benchmark against which the oncological outcome of ablative techniques can be compared.

Our finding of a positive correlation between Fuhrman grade and tumor size supports previous observations. Thompson et al[42] (N = 1523) and Frank et al[43] (N = 2559) both demonstrated that larger tumors were more likely to harbor high-grade disease, with each 1 cm increase in tumor size carrying a 25 - 32% increased risk of high-grade disease (Fuhrman 3 or 4). Analysis of tumors grouped according to various tumor size breakpoints (3 cm[44], 4 cm[45], 5 cm[46]) has also shown a higher prevalence of high-grade disease in the larger size groups. In contrast, Klatte et al classified tumors by an 11 cm breakpoint and found that Fuhrman grade was similar in the two groups[47]. Our finding that Fuhrman grade correlated with tumor stage is also consistent with findings from other studies[48, 49]. The relationship between tumor size and Fuhrman grade has implications for patient counseling and management, particularly if electing active surveillance.

Our study has several shortcomings. It is a retrospective single institution analysis. The small numbers of papillary and chromophobe histological subtypes, and the small number of patients treated with partial nephrectomy were inadequately powered to detect a difference. Likewise, when categorized into 1 cm size intervals, several groups had insufficient numbers to detect a difference. There was no record of when the pre-operative CT was performed, and so we could not standardize the interval between imaging and surgery. Furthermore, there was no uniform protocol for measurement of CT tumor size and pathological tumor size. There was no centralized review of measurements by a single radiologist or pathologist.

A follow-up prospective multi-centre study with larger numbers and a uniform protocol for tumor measurement should be performed to further elucidate the relationship between CT and pathological tumor size. There is also a need for studies examining the correlation between clinical and pathological staging for RCC. Studies that report prognosis according to radiological rather than pathological tumor size would guide us in making treatment decisions based on clinical tumor size. The development and validation of pre-operative prognostic nomograms would also aid decision-making.

Conclusions

There was a statistically significant but small overestimation (3.1 mm) of pathological size by CT overall, but this is of uncertain clinical significance. For some patients, the difference leads to a discrepancy between clinical and pathological staging, which may have implications for pre-operative patient counseling regarding prognosis and choice of treatment strategy.

References

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 2009, New York: Springer, 7

Zisman A, Pantuck A, Dorey F, Said JW, Shvarts O, Quintana D, Gitlitz BJ, deKernion JB, Figlin RA, Belldegrun AS: Improved prognostication of renal cell carcinoma using an integrated staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001, 19: 1649-1657.

Frank I, Blute M, Cheville J, Lohse C, Weaver A, Zincke H: An outcome prediction model for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with radical nephrectomy based on tumor stage, size, grade and necrosis: the SSIGN score. J Urol. 2002, 168: 2395-2400. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64153-5.

Kattan M, Reuter V, Motzer R, Katz J, Russo P: A postoperative prognostic nomogram for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2001, 166: 63-67. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66077-6.

Karakiewicz P, Briganti A, Chun FK, Trinh QD, Perrotte P, Ficarra V, Cindolo L, De la Taille A, Tostain J, Mulders PF, Salamon L, Zigeuner R, Prayer-Galetti T, Chautard D, Valeri A, Lechevallier E, Descotes JL, Lang H, Mejean A, Patard J: Multi-institutional validation of a new renal cancer-specific survival nomogram. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 1316-1322. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1218.

Hafez KS, Fergany AF, Novick AC: Nephron sparing surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma: impact of tumor size on patient survival, tumor recurrence and TNM staging. J Urol. 1999, 162: 1930-33. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68071-8.

Lau W, Blute M, Weaver A, Torres V, Zincke H: Matched comparison of radical nephrectomy vs. nephron-sparing surgery in patients with unilateral renal cell carcinoma and a normal contra lateral kidney. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000, 75: 1236-42. 10.4065/75.12.1236.

Zini L, Perotte P, Capitanio U, Jeldres C, Shariat S, Antebi E, Saad F, Patard J, Montorsi F, Karakiewicz P: Radical versus partial nephrectomy: Effect on overall and non-cancer mortality. Cancer. 2009, 115: 1465-1471. 10.1002/cncr.24035.

Huang W, Elkin E, Levey A, Jang T, Russo P: Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy in patients with small renal tumors - Is there a difference in mortality and cardiovascular outcomes?. J Urol. 2009, 181: 55-62. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.017.

Patard JJ, Shvarts O, Lam JS, Pantuck AJ, Kim HL, Ficarra V, Cindolo L, Han KR, De La Taille A, Tostain J, Artibani W, Abbou C, Lobel B, Chopin DK, Figlin RA, Mulders PF, Belldegrun AS: Safety and efficacy of partial nephrectomy for all T1 tumors based on an international multicenter experience. J Urol. 2004, 171: 2181-85. 10.1097/01.ju.0000124846.37299.5e.

Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Weaver AL, Zincke H: Nephron sparing surgery for appropriately selected renal cell carcinoma between 4 and 7 cm results in outcome similar to radical nephrectomy. J Urol. 2004, 171: 1066-70. 10.1097/01.ju.0000113274.40885.db.

Pahernik S, Roos F, Rohrig B, Wiesner C, Thuroff J: Elective nephron-sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma larger than 4 cm. J Urol. 2008, 179: 71-74. 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.165.

Peycelon M, Hupertan V, Comperat E, Renard-Penna R, Vaessen C, Conort P, Bitker MO, Chartier-Kastler E, Richard F, Roupret M: Long-term outcomes after nephron sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma larger than 4 cm. J Urol. 2009, 181: 35-41. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.025.

Thompson RH, Siddiqui S, Lohse CM, Leibovich BC, Russo P, Blute ML: Partial versus radical nephrectomy for 4 to 7 cm renal cortical tumors. J Urol. 2009, 182: 2601-6. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.087.

Campbell SC, Novick AC, Belldegrun A, Blute ML, Chow GK, Derweesh IH, Faraday MM, Kaouk JH, Leveillee RJ, Matin SF, Russo P, Uzzo RG: Guideline for management of the clinical T1 renal mass. J Urol. 2009, 182: 1271-9. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.004.

Ljungberg B, Cowan NC, Hanbury DC, Hora M, Kuczyk MA, Merseburger AS, Patard JJ, Mulders PF, Sinescu IC: EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2010 update. Eur Urol. 2010, 58: 398-406. 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.032.

Nguyen C, Campbell S, Novick A: Choice of operation for clinically localized renal tumour. Urol Clin North Am. 2008, 35: 645-655. 10.1016/j.ucl.2008.07.002.

Breau RH, Crispen PL, Jimenez RE, Lohse CM, Blute ML, Leibovich BC: Outcome of stage T2 or greater renal cell cancer treated with partial nephrectomy. J Urol. 2010, 183: 903-8. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.037.

Karellas ME, O'Brien MF, Jang TL, Bernstein M, Russo P: Partial nephrectomy for selected renal cortical tumors of >/= 7 cm. BJU Int. 2010, 106: 1484-7. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09405.x.

Kunkle D, Egleston B, Uzzo R: Excise, ablate or observe: the small renal mass dilemma - a meta-analysis and review. J Urol. 2008, 179: 1227-1234. 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.047.

Benway B, Bhayani B: Approach to the small renal mass: weighing treatment options. Curr Urol Rep. 2009, 10: 11-16. 10.1007/s11934-009-0004-0.

Crispen P, Boorjian S, Lohse C, Sebo TS, Cheville JC, Blute ML, Leibovich BC: Outcomes following partial nephrectomy by tumour size. J Urol. 2008, 180: 1912-1917. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.047.

Novara G, Ficarra V, Antonelli A, Artibani W, Bertini R, Carini M, Cosciani Cunico S, Imbimbo C, Longo N, Martignoni G, Martorana G, Minervini A, Mirone V, Montorsi F, Shiavina R, Simeone C, Serni S, Simonato A, Siracusano S, Volpe A, Carmignani G: Validation of the 2009 TNM version in a large multi-institutional cohort of patients treated for renal cell carcinoma: are further improvements needed?. Eur Urol. 2010, 58: 588-95. 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.07.006.

Lee SE, Lee WK, Kim DS, Doo SH, Park HZ, Yoon CY, Hwang SI, Lee HJ, Choe G, Hong SK: Comparison of radiographic and pathologic sizes of renal tumors. World J Urol. 2010, 28: 263-7. 10.1007/s00345-010-0511-0.

Choi JY, Kim BS, Kim TH, Yoo ES, Kwon TG: Correlation between radiologic and pathologic tumor size in localized renal cell carcinoma. Korean J Urol. 2010, 51: 161-4. 10.4111/kju.2010.51.3.161.

Ates F, Akyol I, Sildiroglu O, Kucukodaci Z, Soydan H, Karademir K, Baykal K: Preoperative imaging in renal masses: does size on computed tomography correlate with actual tumor size?. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010, 42: 861-6. 10.1007/s11255-010-9707-x.

Alicioglu B, Kaplan M, Yurut-Caloglu V, Usta U, Levent S: Radiographic size versus surgical size of renal masses: which is the true size of the tumor?. J BUON. 2009, 14: 235-8.

Kurta J, Thompson R, Kundu S, Kaag M, Manion MT, Herr HW, Russo P: Contemporary imaging of patients with a renal mass: does size on computed tomography equal pathological size?. BJU Int. 2008, 103: 24-27. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07941.x.

Mistry R, Manikandan R, Williams P, Philip J, Littler P, Foster CS, Parsons KF: Implications of computer tomography measurement in the management of renal tumors. BMC Urology. 2008, 8: 13-10.1186/1471-2490-8-13.

Kanofsky J, Phillips C, Stifelman M, Taneja S: Impact of discordant radiologic and pathologic tumour size on renal cancer staging. Urology. 2006, 68: 728-731. 10.1016/j.urology.2006.04.042.

Schlomer B, Figenshau R, Yan Y, Bhayani S: How does the radiographic size of a renal mass compare with the pathologic size?. Urology. 2006, 68: 292-295. 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.004.

Yaycioglu O, Rutman M, Balascubramaniam M, Peters KM, Gonzalez JA: Clinical and pathologic tumor size in renal cell carcinoma: difference, correlation, and analysis of the influencing factors. Urology. 2002, 60: 33-38. 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01668-0.

Irani J, Humbert M, Lecocq B, Pires C, Lefebvre O, Dore B: Renal tumor size: comparison between computed tomography and surgical measurements. Eur Urol. 2001, 39: 300-303. 10.1159/000052457.

Herr H, Lee C, Sharma S, Hilton S: Radiographic versus pathologic size of renal tumors: implications for partial nephrectomy. Urology. 2001, 58: 157-160. 10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01173-6.

Herr HW: Radiographic vs surgical size of renal tumors after partial nephrectomy. Br J Urol. 1999, 85: 1-3.

Jamis-Dow C, Choyke P, Jennings S, Linehan W, Thakore K, Walther M: Small (or < 3 cm) renal masses: detection with CT versus US and pathological correlation. Radiology. 1996, 198: 785-788.

Doeuk N, Guo DY, Haddad R, Lau H, Woo HH, Bariol S, Drummond M, Vladica P, Brooks A, Patel MI: Renal cell carcinoma: stage, grade and histology migration over the last 15 years in a large Australian surgical series. BJU Int. 2010,

Hsu PK, Huang HC, Hsieh CC, Hsu HS, Wu YC, Huang MH, Hsu WH: Effect of formalin fixation on tumor size determination in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007, 84: 1825-9. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.016.

Bensalah K, Crepel M, Patard J: Tumor size and nephron-sparing surgery: does it still matter?. Eur Urol. 2008, 53: 691-693. 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.11.023.

Kanao K, Mizuno R, Kikuchi E, Miyajima A, Nakagawa K, Ohigashi T, Nakashima J, Oya M: Preoperative prognostic nomogram (probability table) for renal cell carcinoma based on TNM classification. J Urol. 2009, 181: 480-485. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.017.

Raj G, Thompson R, Leibovich B, Blute M, Russo P, Kattan M: Preoperative nomogram predicting 12-year probability of metastatic renal cancer. J Urol. 2008, 179: 2146-2151. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.101.

Thompson RH, Kurta JM, Kaag M, Tickoo SK, Jundo S, Katz D, Nogueira L, Reuter VE, Russo P: Tumor size is associated with malignant potential in renal cell carcinoma cases. J Urol. 2009, 181: 2033-6. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.027.

Frank I, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Weaver AL, Zincke H: Solid renal tumors: an analysis of pathological features related to tumor size. J Urol. 2003, 170: 2217-20. 10.1097/01.ju.0000095475.12515.5e.

Remzi M, Ozsoy M, Klingler HC, Susani M, Waldert M, Seitz C, Schmidbauer J, Marberger M: Are small renal tumors harmless? Analysis of histopathological features according to tumors 4 cm or less in diameter. J Urol. 2006, 176: 896-9. 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.047.

Bensalah K, Pantuck AJ, Crepel M, Verhoest G, Mejean A, Valeri A, Ficarra V, Pfister C, Ferriere JM, Soulie M, Cindolo L, De La Taille A, Tostain J, Chautard D, Schips L, Zigeuner R, Abbou CC, Lobel B, Salomon L, Lechevallier E, Descotes JL, Guille F, Colombel M, Belldegrun AS, Patard JJ: Prognostic variables to predict cancer-related death in incidental renal tumors. BJU Int. 2008, 102: 1376-80.

Hsu RM, Chan DY, Siegelman SS: Small renal cell carcinomas: correlation of size with tumor stage, nuclear grade and histologic subtype. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004, 182: 551-7.

Klatte T, Patard JJ, Goel RH, Kleid MD, Guille F, Lobel B, Abbou CC, De La Taille A, Tostain J, Cindolo L, Altieri V, Ficarra V, Artibani W, Prayer-Galetti T, Allhoff EP, Schips L, Zigeuner R, Figlin RA, Kabbinavar FF, Pantuck AJ, Belldegrun AS, Lam JS: Prognostic impact of tumor size on pT2 renal cell carcinoma: an international multicenter experience. J Urol. 2007, 178: 35-40. 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.046.

Bretheau D, Lechevallier E, de Fromont M, Sault MC, Rampal M, Coulange C: Prognostic value of nuclear grade of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1995, 76: 2543-9. 10.1002/1097-0142(19951215)76:12<2543::AID-CNCR2820761221>3.0.CO;2-S.

Gudbjartsson T, Hardarson S, Petursdottir V, Thoroddsen A, Magnusson J, Einarsson GV: Histological subtyping and nuclear grading of renal cell carcinoma and their implications for survival: a retrospective nation-wide study of 629 patients. Eur Urol. 2005, 48: 593-600. 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.04.016.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2490/11/2/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NJ drafted the manuscript. ND and DG were responsible for creating and maintaining the Westmead Renal Tumor database. MP conceived the idea of the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeffery, N.N., Douek, N., Guo, D.Y. et al. Discrepancy between radiological and pathological size of renal masses. BMC Urol 11, 2 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-11-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-11-2