Abstract

Background

The open Burch colposuspension, first described in 1961 had been widely employed for the surgical treatment of women with stress urinary incontinence (SUI) caused by urethral hypermobility. We evaluated the long-term efficacy of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension (LBC) for SUI in women.

Methods

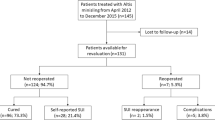

A randomized prospective trial was conducted from September 2010 to January 2013. The extraperitoneal laparoscopic Burch colposuspension was performed by an operator on 96 women, mean age was 54,3 ± 3,7 years all of whom suffered from SUI or mixed urinary incontinence. Patients completed a self-administered the Short Form-36 (SF-36), the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS), the Short Urinary Distress Inventory (SUDI) and Short Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (SIIQ). at both baseline and follow up(6 weeks, 6 months, 18 months postoperatively). The Genito-Urinary Treatment Satisfaction Scale (GUTSS) was used to assess satisfaction with surgery.

Results

After follow up was recorded an improvement of questionnaries scores. The general health score is improved after surgery (2,60 ± 1.02 versus 2,76 ± 1.06) with p = 0.09. The PCS baseline score is 46.29 ± 10.95 versus 49.54 ± 10.41 after treatment with p = 0.01, so there was a significant baseline to follow up improvement. The MCS improved also, infact baseline score is 42.19 ± 12.57 versus 42.70 ± 13.03 with p = 0.87. The SUDI baseline score is 50.22 ± 20.73 versus 23.92 ± 17.90, while SIIQ score is 49.98 ± 23.90 versus 31.40 ± 23.83 with p < 0.01. In both questionnaires there is an improvement. Satisfaction with treatment outcomes from the GUTSS at 6-month follow up is 29.5 ± 6.3 with p = 0.46.

Conclusion

The LBC has significant advantages, without any apparent compromise in short-term and long term outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is defined by the International Continence Society as the complaint of involuntary urinary leakage on effort or exertion, or on sneezing or coughing [1]. It is a common problem. Prevalence has been estimated at 17-45% of adult women in resource-rich countries [2] One cross-sectional study (15,308 women in Norway, aged less than 65 years) found that the prevalence of stress incontinence was 4.7% in women who had not borne a child, 6.9% in women who had had caesarean deliveries only, and 12.2% in women who had had vaginal deliveries only [3]. The causes of SUI are urethral hypermobility, in which there is laxity of pelvic floor support, and intrinsic sphincter dysfunction caused by the inability of the urethral sphincter itself to close [4]. A multitude of surgical and non-surgical treatment modalities has been described to correct SUI [5]. One well-accepted technique for surgical management of urethral hypermobility is the open Burch colposuspension [5–7]. Two to 3 permanent or delayed absorbable sutures are passed through the endopelvic fascia lateral to the midurethra and bladder neck and then through the ipsilateral Cooper's ligament and tied with gentle tension [8] A short-term cure rate (defined as the percentage with complete continence) of 73% to 92%, and a success rate (defined as the percentage with cure or improvement) of 81% to 96% have been reported.[9] This technique's effectiveness continues for the long term; after 5 to 10 years, approximately 70% of patients are still continent.[9, 10] Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension was introduced in the early 1990s for the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) [11] Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension (LBC) has been described using the transperitoneal or extraperitoneal approach, using 3 to 5 trocars. The extraperitoneal route is favored by most authors [15, 21, 18, 27] and is similar to the technique described by Burch [5]. In this approach, the space of Retzius is rapidly dissected using a balloon, or without a balloon by finger and pneumodissection with CO2 [15, 23]. The extraperitoneal approach also avoids intraperitoneal pelvic adhesions, minimizes the risk of intra-abdominal injury, and is associated with a shorter learning curve. The main disadvantage of extraperitoneal laparoscopic colposuspension is the risk of increased absorption of CO2 leading to pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax [16, 28]. The transperitoneal approach is suitable for patients undergoing concomitant pelvic surgery [17, 19, 25, 29, 30]. The operative time with this technique may be prolonged due to the need to take down adhesions, mobilize the bladder, and difficulty in retracting intra-abdominal organs [29]. Laparoscopic pelvic surgery provides better visualization, shorter hospital stay, better cosmetics, less postoperative pain, and faster recovery to normal daily activity [12]. However, despite the renewed interest in the application of laparoscopic technique in the management of SUI, a dichotomy of opinion remains regarding its long-term efficacy.[12] Laparoscopic colposuspension is historically regarded as having good, short-term success rate of over 90% [12, 13] but this rate declines with longer follow-up to 59%-68% [13]. The complication rate related to the laparoscopic approach is higher than the open procedure (5-8% vs. 8-22%)[14]. The most common intraoperative complication is lower urinary tract injury. Bladder injury, which occurs at an incidence of 2.17-18%, is common in patients with prior pelvic surgery [14–20]. Bladder catheter drainage during surgery and meticulous dissection help prevent most bladder injuries. In the majority of cases, these injuries can be managed laparoscopically obviating the need to convert to an open procedure [21]. Conversion rates, especially in the earlier stages of learning, can be as high as 26%[21]. Rare cases of partial ureteral obstruction have been reported[17, 22]. The development of overactive bladder after laparoscopic Burch colposuspension is a well-recognized phenomenon [17, 18, 23–26]. It occurs at an incidence of 2.8%-8% and has been attributed to extensive dissection of the bladder[17, 23, 26]. The incidence of postoperative permanent or transient urinary retention is low (1.8%) [17]. However, there are not many reports on the long-term outcomes of laparoscopic colposuspensions. The purpose of this study was to present the long term results of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension for SUI.

Methods

A randomized prospective trial was conducted from September 2010 to January 2013. The extraperitoneal laparoscopic Burch colposuspension was performed by an operator on 96 women, mean age was 54,3 ± 3,7 years all of whom suffered from SUI or mixed urinary incontinence. At visit patients were evaluated by means of detailed medical and standradised urogynecological history, clinical examination, cough stress test, urinalysis and urine culture, and instrumental examination like full urodynamic study with urethral closure pressure and voiding cystourethrography. [31] All women had urodynamically proven SUI. Inclusion criteria included women with SUI and failed conservative therapy. Exclusion criteria included: previous retropubic continence, intrinsic sphincter dysfunction (abdominal leak point pressure less than 60 cm H2 O), medically unsuitable for laparoscopic or open surgery, and major degrees of coexisting pelvic organ prolapse, requiring surgery other than a simple rectocele repair. Coexisting idiopathic detrusor overactivity was not an exclusion criterion for entry into the study. Urinary urgency, urgency incontinence, and detrusor overactivity were assessed preoperatively and postoperatively. Women were reviewed at 6 weeks, 6 months, 18 months postoperatively. The Short Form-36 (SF-36) was administered at both baseline and follow up [31]. This compares eight scales that can be collapsed into two summary measures assessing physical and mental health, the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS), respectively. In addition, the SF-36 has a general health question (excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor). Only the summary scales and general health question are reported in this study. Summary scores are presented as T-scores with means of 50 and SD of 10 points [32]. Lower scores indicate better general, physical, and mental health using the SF-36 survey. Women completed the Short Urinary Distress Inventory (SUDI) and Short Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (SIIQ) at baseline and follow up.[33] These instruments assess symptom distress and life impact, respectively, of urinary incontinence. At the 6-week postoperative review, data on resumption of normal activities were also collected via standard questioning. Patient satisfaction was assessed on a visual analogue scale (VAS; 0-100 where 100 represented being completely satisfied and 0 completely unsatisfied). At the 6-month review, urodynamics tests were repeated, and the Genito-Urinary Treatment Satisfaction Scale (GUTSS) was used to assess satisfaction with surgery.[34, 35]. The scale range is 0-32, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. An intraoperative cystoscopy was performed on all the women at the end of the procedure to exclude any urethral and bladder injuries. The Foley catheter was removed 24 hr after the operation, and then intermittent self-catheterizations were performed until the postvoid residual urine was less than 50 mL. Normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed using the unpaired Student's t-test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Six-month incidence of stress incontinence or detrusor overactivity symptoms, and the presence of either at urodynamics tests were analysed using logistic regression. Eighteen-month stress incontinence, urgency, and urgency incontinence symptoms were analysed using ordinal logistic regression. For the sensitivity analysis of stress incontinence symptoms at 18 months, we pooled 'occasional' and 'frequent' and added all missing values to this outcome and to the denominator. For the incontinence self-reporting measures (the SUDI, SIIQ) and health status measure, missing scores were imputed using hot deck, where the deck was defined as the treatment group [36] For SF-36 items contributing to the PCS and MCS scales, horizontal mean imputation was used.[37] Between groups comparisons at baseline and follow up were made using the independent t-teat test; for baseline analyses, the dependent t test was used, and for baseline/follow up by group analyses, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used with the baseline scores entered as the covariate. The statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

The preoperative characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. After 6 months SUI is 28% with p = 0.22, detrusor overactivity is 11% with p = 0.88, SUI and/or detrusor overactivity 36% with p = 0.41, patient satisfaction 90% with p = 0.52 (Table 2). Five women had detrusor overactivity on urodynamics before but not after surgery. Nine women developed detrusor overactivity on urodynamics after surgery, (p = 0,67).

We asked all patients to complete the Short Form-36 (SF-36). The general health score is improved after surgery (2,60 ± 1.02 versus 2,76 ± 1.06) with p = 0.09. The Physical Component Summary (PCS) baseline score is 46.29 ± 10.95 versus 49.54 ± 10.41 after treatment with p = 0.01,(Table 3) so there was a significant baseline to follow up improvement. The Mental Component Summary (MCS) improved also, infact baseline score is 42.19 ± 12.57 versus 42.70 ± 13.03 with p = 0.87.(Table 3)

Table 3 also shows the SUDI or SIIQ scales. The SUDI baseline score is 50.22 ± 20.73 versus 23.92 ± 17.90, while SIIQ score is 49.98 ± 23.90 versus 31.40 ± 23.83 with p < 0.01. In both questionnaires there is an improvement. Satisfaction with treatment outcomes from the GUTSS at 6-month follow up is 29.5 ± 6.3 with p = 0.46. (Table 4). At 18 months after surgery the 31% of patients has ocassionally stress incontinence, while 6% frequently stess incontinence(p = 0.38); ocassionaly urinary urgency is recorded in 40%, and 23% like frequently nurinary urgency (p = 0.40); ocassionaly urge incontinence is presented in 39% patients, while 18% like frequentely (p = 0.21).(Table 5). The Burch colposuspension appears to be an effective and durable anti-incontinent procedure[6]. The same surgery, performed by laparoscopic approach, is gaining popularity because it supposedly presents advantages such as, smaller incisions with better esthetic results, easier access to Retzius space, improved visualization of the surgical field, minimal intraoperative blood loss and lower requirement of analgesics in the postoperative period, in addition to lower cost, shorter hospital stay and rehabilitation period of patients[38–40]. Many authors describe cure rates for laparoscopic Burch surgery similar to those obtained with open technique, however with comparatively shorter follow-up[16, 41–43]. LBC has been performed for over a decade with a relatively small number of reported prospective randomised trials [41, 42]. The role of LBC in the treatment of urinary stress incontinence has changed with the introduction of the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure. From our data, rate of cure for stress incontinence at 6-month postoperative urodynamics was 72% for LBC. Presently, there are only a few, small randomised controlled trials comparing LBC and TVT, with relatively small numbers and short follow-up times.[43, 44] TVT is also a minimally invasive procedure that is relatively quick to perform, requiring little equipment, and having a shorter learning curve than LBC. As more evidence is accumulated about the long term success rates of TVT, it may ultimately become the firstline choice for stress incontinence surgery.[6, 7]. A long term series of Burch colposuspensions have demonstrated excellent durability Since the early 1990s, laparoscopic colposuspension has emerged as a treatment modality in an effort to reduce the surgical morbidity associated with the open Burch colposuspension and to achieve a comparable cure rate[17, 44].

Lapitan et al. [45, 46] reviewed 33 trials that involved a total of 2,403 women, who underwent open retropubic colposuspensions and found an overall cure rate between 68.9% and 88.0%. They reported that the overall continence rates were approximately 85-90% within the first year and 70% after five years of treatment.

There are more than 150 published reports about laparoscopic colposuspensions. However, the long-term outcomes of laparoscopic colposuspension are uncertain, due to the limited duration of follow-up in most series. In 2006, the Cochrane Incontinence Group suggested that the laparoscopic colposuspension may be as good as open colposuspension at two years post surgery according to the currently available data [47–50].

Doret at al. observed that long term results with laparoscopic Burch colposuspension are relatively good but a bit lower than those published with traditional open technique. The effects of the learning curve with an evolving technique are to be considered when analyzing the results [51].

Conclusion

The LBC has significant advantages, without any apparent compromise in short-term and long term outcomes. It determines improvement in objective and subjective measures of disease and in patient satisfaction at 6 months,18 months of follow up. Quality of life significantly improves after laparoscopic Burch colposuspension and reoperations are uncommon.

Authors' information

DP:Associate Professor of Urology at University "Federico II" of Naples.

FI: Associate Professor of Urology at University "Federico II" of Naples.

GDL: Consultant, Department of Urology - Hospital Santa Maria delle Grazie

EI: Resident in Urology Training Programme at University Federico II of Naples

GR: Resident in Urology Training Programme at University Federico II of Naples

AR: Resident in Urology Training Programme at University Federico II of Naples

NR: Resident in Urology Training Programme at University Federico II of Naples

BA: Associate Professor of Surgery at University "Federico II" of Naples.

Abbreviations

- (ANCOVA):

-

Analysis of covariance

- (GUTSS):

-

Genito-Urinary Treatment Satisfaction Scale

- (LBC):

-

Laparoscopic Burch colposuspension

- (MCS):

-

Mental Component Summary

- (PCS):

-

Physical Component Summary

- (SF-36):

-

Short Form-36

- (SIIQ):

-

Short Incontinence Impact Questionnaire

- (SUDI):

-

Short Urinary Distress Inventory

- (SUI):

-

Stress urinary incontinence

- (TVT):

-

Tension-free vaginal tape

- (VAS):

-

Visual analogue scale.

References

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, van Kerrebroeck P, Victor A, Wein A: The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2002, 21:167–78.

Jolleys JV: Reported prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in a general practice. BMJ 1988, 296:1300–1302.

Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, et al.: Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med 2003, 348:900–907.

McDougall EM: Laparoscopic management of female urinary incontinence. Urol Clin North Am 2001, 28:145–9.

Burch JC: Urethrovaginal fixation to Cooper's ligament for correction of stress incontinence, cystocele, and prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1961, 81:281–90.

Alcalay M, Monga A, Stanton SL: Burch colposuspension: a 10–20 year follow up. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995, 102:740–5.

Drouin J, Tessier J, Bertrand PE, Schick E: Burch colposuspension: long-term results and review of published reports. Urology 1999, 54:808–14.

Farzaneh Sharifi-Aghdas: Surgical Management of Stress Urinary Incontinence. Journal of Urology 2005,2(4):175–82.

Petri E: Retropubic cystourethropexies. In Textbook of female urology and urogynaecology. 1st edition. Edited by: Cardozo L, Staskin D. London: Martin Dunitz; 2001:513–24.

Eriksen BC, Hagen B, Eik-Nes SH, Molne K, Mjolnerod OK, Romslo I: Long-term effectiveness of the Burch colposuspension in female urinary stress incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1990, 69:45–50.

Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Karram MM, Walters MD, Paraiso MFR: Paraiso Randomised trial of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension versus tension-free vaginal tape: long-term follow up. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2008, 115:219–225.

Lobel RW, Davis GD: Long-term results of laparoscopic Burch urethropexy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1997, 4:341–5.

McDougall EM, Portis A: The laparoscopic bladder neck suspension fails the test of time. Journal of Urology 1999, 161:105. Abst 393

Myers DL, Peipert JF, Rosenblatt PL, Ferland RJ, Jacobson ND: Patient satisfaction with laparoscopic Burch retropubic urethropexy. J Reprod Med 2000, 45:939–43.

Meltomaa S, Haarala M, Makinen J, Kiiholma P: Endoscopic colposuspension with simplified extraperitoneal approach. Tech Urol, 1997, 3:216–221.

Cooper MJ, Cario G, Lam A, Carlton M: A Review of results in a series of 113 laparoscopic colposuspensions. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynecol 1996, 36:44–8.

Liu CY, Paek W: Laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension (Burch procedure). J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1993, 1:31–5.

Saidi MH, Gallagher MS, Skop IP, Saidi JA, Sadler RK, Diaz KC: Extraperitoneal laparoscopic colposuspension: short-term cure rate, complications, and duration of hospital stay in comparison with Burch colposuspension. Obstet Gynecol 1998, 92:619–21.

Brenner B: Comparing the laparoscopic Burch colposuspension and the suburethral sling. N Z Med J 2001, 114:146–148.

Speights SE, Moore RD, Miklos JR: Frequency of lower urinary tract injury at laparoscopic burch and paravaginal repair. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2000, 7:515–8.

Radomski SB, Herschorn S: Laparoscopic Burch bladder neck suspension: early results. Journal of Urology 1996, 155:515–8.

Ferland RD, Robenblatt P: Ureteral compromise after laparoscopic Burch Colpopexy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1999, 6:217–9.

Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Nezhat CR, Rottenberg H: Laparoscopic retropubic cystourethropexy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1994, 1:339–49.

Miannay E, Cosson M, Lanvin D, Querleu D, Crepin G: Comparison of open retropubic and laparoscopic colposuspension for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1998, 79:159–66.

Fatthy H, El-Hao M, Samaha I, Abdallah K: Modified Burch colposuspension: laparoscopy versus laparotomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2001, 8:99–106.

Ou CS, Rowbotham R: Five-year follow-up of laparoscopic bladder neck suspension using synthetic mesh and surgical staples. J Laparoendosc, Adv Tech A 1999, 9:249–52.

Batislam E, Germiyanoglu C, Erol D: Simplification of laparoscopic extraperitoneal colposuspension: results of two-port technique. Intl Urol Nephrol 2000, 32:47–51.

Wolf JS, Monk TG, McDougall EM, McClennan BZ, Clayman RV: The extraperitoneal approach and subcutaneous emphysema are associated with greater absorption of carbon dioxide during laparoscopic renal surgery. Journal of Urology 1995, 154:959–63.

Liu CY: Laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension (Burch procedure): a review of 58 cases. J Reprod Med 1993, 38:526–30.

Lobel RW, Davis GD: Long-term results of laparoscopic Burch urethropexy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1997, 4:341–5.

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B: SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. In Boston, MA. The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre; 1993.

McCall WA: How to Measure in Education. In New York, NY. Macmillan; 1922.

Uebersax J, Wyman J, McClish D, Shumaker F, McKlish J, Santl J: Short forms to assess life-quality and symptoms distress for urinary incontinence in women; the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Uro-Genital Distress Inventory. Neurourol Urodyn 1995, 14:131–9.

Cornish A, Fynes M, Harmer C, Hawthorne G, Rosamilia A, Carey M, et al.: The Genitourinary Treatment Satisfaction Score for continence surgery. Neurourol Urodyn 2001, 20:506–7.

Hawthorne G, Harmer C: GUTSS: The Genito-Urinary Treatment Satisfaction Scale Study. Melbourne, Australia:Centre for Health Program Evaluation; 2000.

Fayers P, Machin D: Quality of life: Assessment, Analysis and Interpretation. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2000.

Downey RG, King C: Missing data in Likert ratings: a comparison of replacement methods. J Gen Psychol 1998, 125:179–91.

Tamussino KF, Zivkov F, Pieber D, Moser F, Haas J, Ralph G: Five-year results after anti-incontinence operations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999, 181:1347–52.

Ross JV: Laparoscopic Burch repair compared to laparotomy Burch for cure of urinary stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 1995, 6:323–8.

Bezerra CA, Machado MT, Juliano RV, Ruano JMC, Barbosa CP, Borreli M, et al.: Laparoscopic Burch surgery in public institution; cost comparative analysis. J Bras Urol 1999, 25:68–72.

Miklos JR, Kohli N: Laparoscopic paravaginal repair plus Burch colposuspension: Review and descriptive technique. Urology 2000,56(Sup 6A):64–9.

Papasakelariou C, Papasakelariou B: Laparoscopic bladder neck suspension. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1997, 4:185–8.

Lobel RW, Davis GD: Long-term results of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1998, 91:55–9.

Moehrer B, Carey M, Wilson D: Laparoscopic colposuspension: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003, 110:230–5.

Moehrer B, Ellis G, Carey M, Wilson PD: Laparoscopic colposuspension for urinary incontinence in women (Cochrane Review). In The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2003.

Valpas A, Kivela A, Penttinen J, Kauko M, Kujansuu E, Tomas E, et al.: Tension-free vaginal tape and laparoscopic mesh colposuspension in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: immediate outcome and complications--a randomised clinical trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2003, 82:665–71.

Persson J, Teleman P, Eten-Bergquist C, Wolner-Hanssen P: Cost analyses based on a prospective, randomised study comparing laparoscopic colposuspension with a tension-free vaginal tape procedure. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002, 81:1066–73.

Vancaillie TG, Schuessler W: Laparoscopic bladder neck suspension. J Laparoendosc Surg 1991, 1:169–73.

Lapitan MC, Cody DJ, Grant AM: Open retropubic colposuspension for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003, 3:217–219.

Dean NM, Ellis G, Wilson PD, Herbison GP: Laparoscopic colposuspension for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006, 3:245–247.

Doret M, Golfier F, Raudrant D: Laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension (Burch procedure). Techniques and continence results. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 2000,29(7):650–4.

Declarations

Publication of this article has come from personal funds.

This article has been published as part of BMC Surgery Volume 13 Supplement 2, 2013: Proceedings from the 26th National Congress of the Italian Society of Geriatric Surgery. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcsurg/supplements/13/S2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DP: conception and design, interpretation of data, given final approval of the version to be published.

FI: conception and design, interpretation of data, given final approval of the version to be published

GDL: acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, given final approval of the version to be published

EI: acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, given final approval of the version to be published

GR acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, given final approval of the version to be published

AR acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, given final approval of the version to be published

NR acquisition of data, drafting the manuscript, given final approval of the version to be published

BA: critical revision, interpretation of data, given final approval of the version to be published

This article [1] has been retracted by the authors because it contains large portions of text that were duplicated from a number of pervious publications including Rofeim et al. [2], Carey et al. [3] and Hong et al. [4]. The authors apologise for failing to cite these articles.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prezioso, D., Iacono, F., Di Lauro, G. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Stress urinary incontinence: long-term results of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension. BMC Surg 13 (Suppl 2), 2 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S38

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S38