Abstract

Background

Previous studies have suggested an association between sleep duration and cancer. However, the information on sleep duration regard to risk of lung cancer is scanty.

Methods

Analysed data comprised prospective population-based cohort of 2586 men (aged 42–60 years) from Eastern Finland. Baseline survey and clinical examinations took place 1984–1989, and diagnosed lung cancers were obtained until the end of 2011 through linkage with the Finnish Cancer Registry. Self-reported sleep was categorized as ≤6.5 h, 7–7.5 h, and ≥8 h. Subjects with prior history of cancer or psychotropic medication (hypnotics or sedatives) were excluded from the analyses. Cox proportional hazards models with adjustments for possible confounders were used to examine the association.

Results

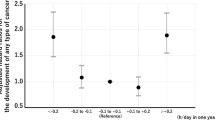

Significant association between sleep duration and increased lung cancer risk was observed after adjustments for age, examination years, cumulative smoking history, family cancer history and Human Population Laboratory Depression scale scores (HR 2.12, 95% CI 1.17-3.85 for ≤6.5 h sleep, and HR 1.88, 95% CI 1.09-3.22 for ≥8 h sleep). Associations were even stronger among current smokers (HR 2.23, 95% CI 1.14-4.34 for ≤6.5 h sleep, and HR 2.09, 95% CI 1.14-3.81 for ≥8 h sleep). After further adjustments for alcohol consumption, physical activity, body mass index, marital status, education years, night work, employment status, asthma and chronic bronchitis, the association remained significant both in the whole study population and among smokers. When cumulative smoking history was replaced by current smoking in the adjustments, the increased risk was limited to those who slept <6.5 h.

Conclusions

Sleep duration of less than 7–7.5 hours or more than 7–7.5 hours associates with increased lung cancer risk. The physiological factors underlying the association are complex, and they may relate to melatonin excretion patterns, low-grade inflammation in cancer development process or disruptions in circadian rhythmicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer is estimated to account for 8.3% of men’s cancer cases globally [1]. Among all types of cancers worldwide, lung cancer incidence is highest [2] and in Finland it comes second [3] after prostate cancer. Previous studies [4, 5] have identified numerous factors to increase risk of lung cancer, such as smoking history, previous lung disease (bronchitis, asthma, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, or obstructive sleep apnoea), environmental exposures, and genetic predisposition.

In addition to established risk factors, it has been suggested that sleep duration may associate with cancer development. Both short and long sleep duration are proposed to be a determinants of increased cancer risk [6]. One possible factor underlying the association is melatonin hormone, which represents the most stable and reliable biomarker of the central circadian pacemaker [7, 8], and may play a role in lung cancer tumor growth [9, 10]. This suggestion is supported by the observations of severe disruptions in circadian rhythms among lung cancer patients [11–15]. These circadian rhythm disruptions consists of a loss of rhythmicity in neuroendocrine and immune parameters [11], as well as disturbed daily sleep-activity cycles [12–15]. Our focus is on altered sleep duration, which can be one of the symptoms of a circadian rhythm sleep disorders [7].

Most of previous studies have proposed nightly sleep less than 6–7 hours to increase risk of cancer in general [16], and specifically prostate cancer [17], breast cancer [18–20] and colorectal adenoma [21]. One recently conducted prospective follow-up study found U-shaped association between sleep duration and colorectal cancer incidence in postmenopausal women [22]. Furthermore, circadian rhythm sleep disorders [8, 23] have shown the relation between sleep and increased cancer risk.

Our focus is on the relationship between lung cancer and altered sleep duration. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous prospective cohort studies on this topic. To assess the possible association between sleeping hours and increased lung cancer risk, we conducted the prospective cohort study among 2586 ageing men from Eastern Finland.

Methods

Study population

The prospective cohort Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Study (KIHD) participants were a randomly selected sample from general population in Eastern Finland [24]. Baseline examinations during 1984–1989 were conducted in 2682 men (82.9% of those invited) aged 42–60 years, living in Kuopio or surrounding rural area. Men having cancer history (n = 51, 1.9%), or using hypnotics or sedatives (n = 45, 1.7%) at baseline were excluded, leaving total of 2586 respondents. Participants provided written informed consent after full explanation of study, and the Research Ethics Committee of Kuopio University approved the study protocol.

Outcome

Diagnosed lung cancers (n = 81, 3.1%) occurring from two years after baseline until end of 2011 were included. To rule out the reverse-causation we restricted our sample to those who had had cancer at least two years at the baseline. Median follow-up time was 23 years (25th-75th percentiles were 18–25 years). Lung cancer diagnoses were ascertained by the individual social security number linkage with the Finnish Cancer Registry. Diagnoses were classified according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8, −9, and −10).

Baseline measures

Sleep

Self-administered questionnaires were recorded by participants and checked by an interviewer. Sleep duration was asked: ‘How many hours do you usually sleep at night?’ Response alternatives were: <6 h, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8, 8.5, 9, 9.5, and >10 h. Crude lung cancer incidence rate ratios were lowest in 7 h (1.21 cases/1 000 person years) and 7.5 h (0.90 cases/1 000 person years) of sleep, and thus sleep duration was divided into three categories: ≤6.5 h, 7–7.5 h, and ≥8 h. Comparable reference sleep duration category is presented in previous cancer and sleep studies [25]. Other sleep questions were: ‘Do you have nightly breathing disruptions?’ (yes/no), and ‘How often do you have difficulties to fall asleep, or staying asleep?’ (never or seldom/sometimes/frequently).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 18-item Human Population Laboratory Depression Scale HPL; [26]. Scale items included mood disturbance, negative self-concept, energy loss, poor appetite, concentration difficulty, and psychomotor agitation. The scale was developed especially for screening general population samples, and it also conceptually resembles other brief symptom checklists such as the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale CES-D; [27, 28]. The HPL Depression score is generated by assigning one point for each true or false answer that is indicative for depression (range 0–18). To avoid collinearity, insomnia was excluded from the scale.

Health and sociodemographic background

Participants completed questionnaires concerning medication (hypnotics, sedatives and antidepressants), and history of physician-diagnosed illnesses (cancers, chronic bronchitis, asthma, and family cancer history). To assess physical activity, the 12-Month Physical Activity questionnaire [29] was applied. The checklist included the most common physical activities (walking, jogging, skiing, bicycling, swimming, games) of Finnish middle-aged men. For each activity performed, the subjects were asked to record the frequency, average duration and intensity. The energy expenditure from physical activity was expressed as kcal/day.

Body mass index (BMI) was computed as the ratio of weight (kilograms) to the square of height (meters). Current smoking behavior was assessed with three questions: 1) Have you ever smoked? Yes/no, 2) Do you smoke daily during last year? Yes/no, and 3) When have you smoked last time? (Less than month is defined as current smoker). Cumulative smoking history (pack-years) was estimated as product of years smoked and number of tobacco products smoked daily at the time of examination. Alcohol consumption (g/wk) was assessed with a structured quantity-frequency method using the Nordic Alcohol Consumption Inventory for drinking behavior over previous 12 months [30]. Respondents were asked for total years of education, marital status (married or living with spouse vs. living alone), working time (day shift vs. night shift), and employment status (employed vs. unemployed or retired).

Statistics

According to variable type and distribution, baseline variables were displayed by the sleep categories with Kruskall-Wallis or χ2 test p-values. Moreover, correlation matrix for the continuous variables was made. Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Mantel-Cox log-rank test) differed significantly (p-value 0.04) between sleep duration categories allowing Cox proportional hazards model application. Covariates were selected based on factors affecting sleep [31] and lung cancer development [4, 5]. To compute hazard ratios (HR) and confidence intervals (95% CI), we first built a Modela that was adjusted for age and examination years. Modela was further adjusted for cumulative smoking history (pack-years) (Modelb), and family cancer history and HPL scale scores (Modelc). Modelc was further adjusted for alcohol consumption, physical activity and BMI (Modeld), education years, marital status, working time and employment status (Modele), and asthma and chronic bronchitis (Modelf). Stratified analyses for whole study population and smokers were formed for following reasons: 1) Smoking is an established risk for lung cancer [32], and 2) We observed substantially more new lung cancer cases among smokers within ≤6.5 h, 7–7.5 h and ≥8 h sleep groups (cancer cases 18, 18, and 32, respectively) than among nonsmokers (cancer cases 3, 6, and 4, respectively). Analyses were conducted with SPSS software (IBM Company, SPSS Statistics version 19.0, United States).

Results

Table 1 displays baseline characteristics according to sleep categories. Smoking, BMI, education years, HPL scale scores, night work, employment status, chronic bronchitis, frequent insomnia and nightly breathing disruptions associated with sleep duration. Table 2 demonstrates the correlations between continuous baseline variables. Education years and HPL scores had significant correlations with all other continuous variables including sleeping hours. Furthermore, sleeping hours correlated with cumulative smoking history.

We carried out proportional hazards analysis with adjustments for possible confounders. As a result, approximately twofold risk for lung cancer was observed in the ≤6.5 h and ≥8 h sleep groups both in the whole study population and among smokers (Table 3). To assess the effect of current smoking, we performed Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, examination year and current smoking in the whole study population. Association between ≥8 h sleep and lung cancer lost significance (HR 1.54, 95% CI 0.92-2.58), but remained in the ≤6.5 h sleep (HR 1.82, 95% CI 1.01-3.28).

We further examined other sleep variables. Nightly breathing disruptions and frequent insomnia were not associated with incidence of lung cancer (age-adjusted HR 1.36, 95% CI 0.75-2.47 and HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.72-1.89, respectively). These conditions cumulated in men with sleep of 6.5 h or less (Table 1).

Discussion

Summary of main findings

Sleep duration of less than 7–7.5 hours or more than 7–7.5 hours associates with increased lung cancer risk in ageing men irrespective of age, cumulative smoking history, family cancer history, night work, health behavior, sociodemographic characteristics and previous inflammatory lung diseases. However, adjusting for current smoking instead of cumulative smoking history, limited the increased risk to the men with nightly sleep 6.5 h or less.

Comparison with previous literature

In this prospective population-based study we observed an association between sleep duration and moderately increased lung cancer risk. Comparable association has been found in the risk of colorectal cancer [22] and in all-cause mortality [31]. Recently conducted meta-analysis concerning sleep duration and breast, prostate, endometrial, thyroid, ovarian and colorectal cancer risk [25] suggests that sleep duration and cancer are not connected to each other. Nevertheless, in the subgroup analyses (3 studies included in) the researchers found higher colorectal cancer risk in the long sleep group. However, the number of sleep duration and cancer risk studies is small, as well as the number of studies concerning different cancer types.

Smoking is well-known risk for lung cancer [32], which was clearly demonstrated also in our study as a substantially higher incidence of lung cancer cases among smokers. Smoking is also connected with depression [33] and sleep disorders [34]. Regular smoking impairs the nightly sleep structure due to the biological effects of nicotine [35], which was observed in our study too.

In addition to smoking, diet and body weight affect both sleep and cancer. In the sleep perspective, the ideal body mass index goes hand in hand with sleep of approximately 7 hours [36], whereas cancer can induce cachexia including loss of appetite, weight loss and hypermetabolism [37].

Overall, a number of possible pathways underlying the association between sleep duration and cancer have been proposed. They relate among other things to clock-gene deregulation induced tumor genesis and progression of cancer [38], immunosuppression due to deprivation or restriction of sleep [39], and altered melatonin secretion patterns, such as timing [40, 41], amount [42, 43], and secretion duration [44]. Melatonin has oncostative properties in tumors, including antioxidant effects, modulation of cell cycle and apoptosis, inhibition of telomerase activity and metastasis, stimulation of cell differentiation, and prevention of chronodisruption CD; [45].

Lung cancer patients have frequently CD [13, 14] with severe alterations of neuroendocrine and immunological factors [11]. However, shift work with CD has been classified as a probable, group 2A carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [46]. Shift work can lead to CD including physiological, endocrinological, and sleep-wake cycle alterations, which may increase the risk for breast, endometrial, prostate and colon cancer [8, 23].

In the sleep perspective, circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSD) include a variety of conditions such as: time zone change, shift work sleep disorder, irregular sleep-wake rhythm, free-running disorder, delayed sleep phase disorder, and advanced sleep phase disorder [7, 47]. CRSDs relate to both timing and duration of sleep, in other words, ‘The essential feature of CRSDs is a persistent or recurrent pattern of sleep disturbance primarily due to alterations in the circadian timekeeping system or a misalignment between the endogenous circadian rhythm and exogenous factors that affect the timing or duration of sleep [7]’. We were interested in altered sleep duration, which can be one symptom of a circadian rhythm sleep disorders [7].

Inflammatory processes are one etiological factor in the lung cancer development [48]. Sleep and immunity have a complex relation, where poor sleep may suppress immunity [39], and in turn, chronic low-grade inflammation may induce sleepiness, fatigue and reduced quality of sleep [49].

Strengths and limitations

Our study comprised regionally representative sample of ageing men with high participation rate. The follow-up information on lung cancer diagnoses was inclusive. All cancer diseases diagnosed in Finland since 1953 have been registered to the Finnish Cancer Registry, which coverage is virtually complete without loss to follow-up [50]. We were able to measure various covariates, such as body mass index and depressive symptoms, which affect sleep and/or lung cancer risk. Also the exclusion of those having cancer diagnosis at baseline or within the two years following improved assessment of association, because exposures were measured before disease onset. To avoid confounding effect, exclusion of hypnotics and sedative users were made at the baseline.

Nevertheless, following limitations in the study need to be considered while interpreting the results. (i) Our observations cannot be generalized to women and younger men. (ii) We were not able to measure all known lung cancer risk factors, like environmental exposures, as well as the changes in sleep duration and health behavior during the follow up time. (iii) Information on sleeping hours can lead to misclassification, because self-reported hours tend to be greater than objectively measured hours [51]. Furthermore, sleep was measured as a single time point measurement. (iv) The number of new lung cancer cases was small during follow-up time. (v) We were not able to assess the effect of melatonin intake. However, the use of melatonin was low in Finland during 1997-2007 [52].

Conclusions

Sleep duration of less than 7–7.5 hours or more than 7–7.5 hours associates with increased lung cancer risk irrespective of age, health behavior, previous inflammatory lung diseases and sociodemographic status. However, adjusting for current smoking instead of cumulative smoking history, limited the increased risk to the men with nightly sleep 6.5 h or less. The physiological factors underlying the association are complex, and may relate to melatonin excretion patterns, low-grade inflammation in cancer development process, or disruptions in circadian rhythmicity.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CD:

-

Chronodisruption

- CRDS:

-

Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

- HR:

-

Hazard Ratio

- HPL:

-

Human Population Laboratory Depression Scale

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- KIHD:

-

Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Study.

References

Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J: Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2013, 1: 1133-1145.

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin : Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide. [http://globocan.iarc.fr]

Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, Johannesen TB, Klint Å, Køtlum JE, Milter MC, Ólafsdóttir E, Pukkala E, Storm HH: Cancer incidence, mortality, prevalence and survival in the nordic countries. [http://www.ancr.nu]

Flaherty KR, Herridge MS: Clinical year in review II: Lung cancer, sleep apnea, interventional pulmonary/pleural disease, cystic fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011, 8: 398-403. 10.1513/pats.201108-044TT.

Cassidy A, Myles JP, Liloglou T, Duffy SW, Field JK: Defining high-risk individuals in a population-based molecular-epidemiological study of lung cancer. Int J Oncol. 2006, 28: 1295-1301.

Erren TC: Sleep duration and cancer risk: time to use a “sleep-years” index?. Cancer Causes Control. 2012, 23: 1399-1403. 10.1007/s10552-012-0027-6.

Sack RL, Auckley D, Auger RR, Carskadon MA, Wright KP, Vitiello MV, Zhdanova IV: Circadian rhythm sleep disorders: Part I, basic principles, shift work and jet lag disorders. An American Academy of sleep medicine review. Sleep. 2007, 30: 1460-1483.

Blask DE: Melatonin, sleep disturbance and cancer risk. Sleep Med Rev. 2009, 13: 257-264. 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.07.007.

Fic M, Podhorska-Okolow M, Dziegiel P, Gebarowska E, Wysocka T, Drag-Zalesinska M, Zabel M: Effect of melatonin on cytotoxicity of doxorubicin toward selected cell lines (human keratinocytes, lung cancer cell line A-549, laryngeal cancer cell line hep-2). In Vivo. 2007, 21: 513-518.

Vesnushkin GM, Plotnikova NA, Semenchenko AV, Anisimov VN: Melatonin inhibits urethane-induced carcinogenesis tumors in murine lung. Vopr Onkol. 2006, 52: 164-168.

Mazzoccoli G, Tarquini R, Durfort T, Francois JC: Chronodisruption in lung cancer and possible therapeutic approaches. Biomed Pharmacother. 2011, 65: 500-508. 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.06.004.

Grutsch JF, Wood PA, Du-Quiton J, Reynolds JL, Lis CG, Levin RD, Ann Daehler M, Gupta D, Quiton DF, Hrushesky WJ: Validation of actigraphy to assess circadian organization and sleep quality in patients with advanced lung cancer. J Circadia Rhythms. 2011, 18: 1-12.

Du-Quiton J, Wood PA, Burch JB, Grutsch JF, Gupta D, Tyer K, Lis CG, Levin RD, Quiton DF, Reynolds JL, Hrushesky WJ: Actigraphic assessment of daily sleep-activity pattern abnormalities reflects self-assessed depression and anxiety in outpatients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Psycho Oncol. 2010, 19: 180-189. 10.1002/pon.1539.

Vena C, Parker K, Allen R, Bliwise D, Jain S, Kimble L: Sleep-wake disturbances and quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006, 1: 761-769.

Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Dhruva A, Dunn LB, Langford DJ, Cataldo JK, Baggoll CR, Merriman JD, Dodd M, Lee K, West C, Paul SM, Aouizerat BE: Evidence of associations between cytokine genes and subjective reports of sleep disturbance in oncology patients and their family caregivers. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e40560-10.1371/journal.pone.0040560.

von Ruesten A, Weikert C, Fietze I, Boeing H: Association of sleep duration with chronic diseases in the european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)-potsdam study. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e30972-10.1371/journal.pone.0030972.

Kakizaki M, Inoue K, Kuriyama S, Sone T, Matsuda-Ohmori K, Nakaya N, Fukudo S, Tsuji I: Sleep duration and the risk of prostate cancer: the Ohsaki cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2008, 8: 176-178.

Kakizaki M, Kuriyama S, Sone T, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Hozawa A, Nakaya N, Fukudo S, Tsuji I: Sleep duration and the risk of breast cancer: the Ohsaki cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2008, 4: 1502-1505.

Verkasalo PK, Lillberg K, Stevens RG, Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J: Sleep duration and breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Res. 2005, 15: 9595-9600.

Wu AH, Wang R, Koh WP, Stanczyk FZ, Lee HP, Yu MC: Sleep duration, melatonin and breast cancer among Chinese women in Singapore. Carcinogenesis. 2008, 29: 1244-1248. 10.1093/carcin/bgn100.

Thompson CL, Larkin EK, Patel S, Berger NA, Redline S, Li L: Short duration of sleep increases risk of colorectal adenoma. Cancer. 2011, 15: 841-847.

Jiao L, Duan Z, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Hale L, White DL, El-Serag HB: Sleep duration and incidence of colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. Br J Cancer. 2013, 108: 213-221. 10.1038/bjc.2012.561.

Erren TC, Pape HG, Reiter RJ, Piekarski C: Chronodisruption and cancer. Naturwissenschaften. 2008, 95: 367-382. 10.1007/s00114-007-0335-y.

Salonen JT: Is there a continuing need for longitudinal epidemiologic research? The Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease risk factor study. Ann Clin Res. 1996, 41: 541-549.

Lu Y, Tian N, Yin J, Shi Y, Huang Z: Association between sleep duration and cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS One. 2013, 4: e74723-

Kaplan GA, Roberts RE, Camacho TC, Coyne JC: Psychosocial predictors of depression. prospective evidence from the Human Population Laboratory studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1987, 125: 206-220.

Roberts RE: Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Mexican Americans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1981, 169: 213-219. 10.1097/00005053-198104000-00002.

Roberts RE, O’Keefe SJ: Sex differences in depression re-examined. J Health Soc Behav. 1981, 22: 394-400. 10.2307/2136680.

Salonen JT, Slater JS, Tuomilehto J, Rauramaa R: Leisure time and occupational physical activity: risk of death from ischemic heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1988, 127: 87-94.

Kauhanen J, Julkunen J, Salonen JT: Coping with inner feelings and stress: heavy alcohol use in the context of alexithymia. Behav Med. 1992, 18: 121-126. 10.1080/08964289.1992.9936962.

Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA: Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010, 33: 585-592.

Lee PN, Forey BA, Coombs KJ: Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence in the 1900s relating smoking to lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012, 12: 385-10.1186/1471-2407-12-385.

Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O’Loughlin J, Rehm J: A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009, 22: 356-

Bixler E: Sleep and society: an epidemiological perspective. Sleep Med. 2009, 10 (Suppl 1): 3-6.

Zhang L, Samet J, Caffo B, Punjabi NM: Cigarette smoking and nocturnal sleep architecture. Am J Epidemiol. 2006, 15: 529-537.

Adamkova V, Hubacek JA, Lanska V, Vrablik M, Kralova Lesna I, Suchanek P, Zimmelova P, Veleminsky M: Association between duration of the sleep and body weight. Physiol Res. 2009, 58 (Suppl 1): 27-31.

Giacosa A, Rondanelli M: Fish oil and treatment of cancer cachexia. Genes Nutr. 2008, 3: 25-28. 10.1007/s12263-008-0078-1.

Savvidis C, Koutsilieris M: Circadian rhythm disruption in cancer biology. Mol Med. 2012, 6: 1249-1260.

Bollinger T, Bollinger A, Oster H, Solbach W: Sleep, immunity, and circadian clocks: a mechanistic model. Gerontology. 2010, 56: 574-580. 10.1159/000281827.

Pandi-Perumal SR, Smits M, Spence W, Srinivasan V, Cardinali DP, Lowe D, Kayumov L: Dim light melatonin onset (DLMO): a tool for the analysis of circadian phase in human sleep and chronobiological disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 30: 1-11.

Claustrat B, Brun J, Chazot G: The basic physiology and pathophysiology of melatonin. Sleep Med Rev. 2005, 9: 11-24. 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.08.001.

Tamarkin L, Danforth D, Lichter A, DeMoss E, Cohen M, Chabner B, Lippman M: Decreased nocturnal plasma melatonin peak in patients with estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Science. 1982, 28: 1003-1005.

Schernhammer ES, Hankinson SE: Urinary melatonin levels and breast cancer risk. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2005, 20: 1084-1087.

Kripke DF, Youngstedt SD, Rex KM, Klauber MR, Elliott JA: Melatonin excretion with affect disorders over age 60. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 1: 47-54.

Mediavilla MD, Sanchez-Barcelo EJ, Tan DX, Manchester L, Reiter RJ: Basic mechanisms involved in the anti-cancer effects of melatonin. Curr Med Chem. 2010, 17: 4462-4481. 10.2174/092986710794183015.

Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Altieri A, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Cogliano V: Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol. 2007, 8: 1065-1066. 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70373-X.

Sack RL, Auckley D, Auger RR, Carskadon MA, Wright KP, Vitiello MV, Zhdanova IV: Circadian rhythm sleep disorders: Part II, advanced sleep phase disorder, delayed sleep phase disorder, free-running disorder, and irregular sleep-wake rhythm. An American Academy of sleep medicine review. Sleep. 2007, 30: 1484-1501.

Shi J, Chatterjee N, Rotunno M, Wang Y, Pesatori AC, Consonni D, Li P, Wheeler W, Broderick P, Henrion M, Eisen T, Wang Z, Cuen W, Dong Q, Albanes D, Thun M, Spitz MR, Bertazzi PA, Caporaso NE, Chanock SJ, Amos CI, Houlston RS, Landi MT: Inherited variation at chromosome 12p13.33, including RAD52, influences the risk of squamous cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2: 131-139. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0246.

Rohleder N, Aringer M, Boentert M: Role of interleukin-6 in stress, sleep, and fatigue. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012, 1261: 88-96. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06634.x.

Teppo L, Pukkala E, Lehtonen M: Data quality and quality control of a population-based cancer registry. Experience in Finland. Acta Oncol. 1994, 33: 365-369. 10.3109/02841869409098430.

Kripke DF, Langer RD, Elliott JA, Klauber MR, Rex KM: Mortality related to actigraphic long and short sleep. Sleep Med. 2011, 12: 28-33. 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.04.016.

National Agency for Medicines: Finnish statistics on medicines 2007. [http://www.kela.fi/documents/12099/12170/laaketilasto07_2.pdf]

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/295/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the former personnel of the Research Institute of Public Health for their valuable work in the KIHD data gathering, and Kimmo Ronkainen, M.Sc, for data management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ML carried out data analyses and drafted the manuscript. SL, TT, AE, and JK participated to data analyses, and drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Luojus, M.K., Lehto, S.M., Tolmunen, T. et al. Sleep duration and incidence of lung cancer in ageing men. BMC Public Health 14, 295 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-295

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-295