Abstract

Background

Cause-of-death data linked to information on socioeconomic position form one of the most important sources of information about health inequalities in many countries. The proportion of deaths from ill-defined conditions is one of the indicators of the quality of cause-of-death data. We investigated educational differences in the use of ill-defined causes of death in official mortality statistics.

Methods

Using age-standardized mortality rates from 16 European countries, we calculated the proportion of all deaths in each educational group that were classified as due to “Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions”. We tested if this proportion differed across educational groups using Chi-square tests.

Results

The proportion of ill-defined causes of death was lower than 6.5% among men and 4.5% among women in all European countries, without any clear geographical pattern. This proportion statistically significantly differed by educational groups in several countries with in most cases a higher proportion among less than secondary educated people compared with tertiary educated people.

Conclusions

We found evidence for educational differences in the distribution of ill-defined causes of death. However, the differences between educational groups were small suggesting that socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific mortality in Europe are not likely to be biased.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cause-of-death statistics are an important source of information for epidemiological research and policy decisions. Their reliability is essential, not only for assessing trends and variations in average population health, but also for assessing the magnitude of inequalities in health between population groups. Indeed, many studies of health inequalities make extensive use of cause-specific mortality data [1–4], and it is therefore important to ensure that there are no differences between socioeconomic groups in the quality of cause-of-death information.

The proportion of deaths from ill-defined conditions is one of the commonly used indicators for the quality of cause-of-death data [5–8]. Deaths should be classified as due to ill-defined conditions only in a few cases when the real cause of death cannot be determined. However, in practice, deaths may also be classified as ill-defined when the certifying physician has insufficient knowledge of the disease(s) causing death, and/or has not completed the death certificate properly. It is likely that ill-defined causes of death hide important pathologies, and a high proportion of ill-defined causes of death may therefore lead to an underestimation of the mortality rates from well-defined causes of death, such as ischemic heart disease (IHD), suicide or injuries [8–11]. On the other hand, a very low proportion of ill-defined conditions does not necessarily imply a high quality of cause-of-death information, because it does not exclude other forms of misclassification such as a tendency to over-report one specific cause of death (e.g., cardiovascular disease) at the expense of another [12].

Previous studies have shown that deaths from ill-defined conditions are more common in ethnic minorities [9], among old people living alone and in very marginal population groups, such as homeless people [13, 14]. Although a Dutch study reported higher mortality due to ill-defined conditions in low-income boroughs of Amsterdam [15], studies investigating socioeconomic differences in the proportion of ill-defined causes of death are rare and were not conducted in such extent as our study does. Such inequalities may occur, for example, if lower socioeconomic groups have less access to good quality health care [16, 17] and, as a consequence, die under circumstances in which their diagnosis is less well-established than is normally the case for patients with a higher socioeconomic position.

Socioeconomic differences in the proportion of ill-defined causes of death may lead to under- or overestimation of socioeconomic differences in well-defined causes of death. The aim of the present study was therefore to examine whether there are educational differences in the proportion of ill-defined causes of death among men and women in 16 European populations and to investigate if these differences harm the socioeconomic differences in mortality from specific causes of deaths, especially ischemic heart disease or suicide.

Methods

We analysed mortality data from 16 European populations as collected and harmonized in the EURO-GBD-SE project [18]. Data come from longitudinal (Finland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, England and Wales, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Austria, the Basque Country, Madrid, Turin, Tuscany), repeated cross-sectional (Barcelona) or cross-sectional unlinked (Hungary, Czech Republic, Poland, Estonia) studies in national, regional or urban populations in the time period between 1998 and 2007 (Additional file 1: Table S1 in the supplementary online material). We combined all Spanish and all Italian datasets to ensure adequate number of deaths.

Completed education was categorized into three groups according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED): less-than-secondary education (ISCED 0, 1, 2; ‘low’), secondary education (ISCED 3, 4; ‘mid’) and tertiary education (ISCED 5, 6; ‘high’). The share of individuals with unknown education was in most populations below 2.3% except in France (6.0%) and Switzerland (6.1%). These individuals were excluded from the analyses. Ill-defined causes of death were defined as codes 780–799 (“Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions”) or R00–R99 (“Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified”), according to respectively the ninth or tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases. Examples of specific entities within this chapter are ‘sudden death’, ‘senility’ or ‘old age’.

Analyses were conducted by country, sex and education for the age range 30–79. The proportion of ill-defined causes of death was computed as the share of the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) for ill-defined conditions on the all-cause ASMR. We used direct standardization with European Standard Population as standard [19]. We performed Chi-square tests of independence to assess if the proportion of ill-defined causes of death differed by educational group [20]. All tests were performed at the 5% significance level.

Further, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we estimated to what extent any misclassification of well-defined causes of death as ill-defined condition may affect socioeconomic inequalities in those well-defined causes. We used IHD (ICD-9: 410–414, ICD-10: I20–I25) and suicide (ICD-9: E950–959; ICD-10: X60–X84, Y87.0) as examples for the misclassification. We conducted the sensitivity analysis by adding 50% (respectively 20%) of deaths from ill-defined conditions to IHD deaths (resp. suicide deaths) in each educational group. We assessed relative inequalities as relative risks using Poisson regression. Subsequently, we compared the ranking of socioeconomic inequalities in IHD and suicide mortality between European countries before and after the redistribution. The ranking was calculated by the Spearman correlation.

Results

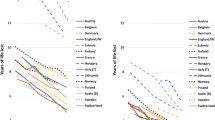

The proportion of ill-defined causes of death varied across European countries, but without any clear geographical pattern (Figure 1). The proportion ranged from 0.1% in Hungary to 6.2% in Poland among men, and from 0.05% in Hungary to 4.3% in the Netherlands among women. For both men and women, proportions of ill-defined causes of death lower than 1% were found in Finland, England and Wales, Scotland, Austria, Italy, Hungary, Czech Republic and Lithuania. Proportions of ill-defined causes of death higher than 3% were observed in Norway, Denmark, Netherlands, France, Switzerland and Poland.

The distribution of ill-defined causes of death differed by educational level in Denmark, England and Wales, Belgium, Hungary, Czech Republic, Poland and Estonia among men, and in Poland among women with the tendency of a higher proportion among low educated, and in Switzerland (men and women) and Italy (men) with the tendency of a higher proportion among high educated (Table 1). Absolute differences between the low and high educated are, however, small: generally less than one percentage point, with exception of Polish men among whom the difference is 2.9%-points.

Although in general the proportion of ill-defined causes of death on total mortality was higher among lower educated, we observed a tendency for a higher proportion among high educated in Finland (women), Norway, Netherlands (men), France, Switzerland and Italy (men). This is the case for countries which combine relatively low total mortality rate with relatively high mortality rate from ill-defined conditions among high educated individuals.

Based on the sensitivity analysis, relative inequalities in IHD and suicide mortality changed considerably only among men in Poland after the redistribution of the ill-defined causes of death (Tables 2 and 3). These redistributions did not change the rank order for relative inequalities in IHD mortality (rho: men, women = 0.956) and suicide mortality (rho: men = 0.982; women = 0.970) among the European countries investigated.

Discussion

This study had a broad geographical scope and included countries with different educational systems and different cause-of-death certifying and coding practices. Although we put much effort in harmonizing the data, there are some methodological issues that should be addressed.

First, foreigners and people born outside mainland were excluded from the Swiss and French dataset, respectively. If cause-of-death certification is more incomplete among foreigners [21], this will have led to an underestimation of the proportion of ill-defined causes of death in these countries. Spain and Italy were represented by cities or regions. If cause-of-death information is more complete in these urban areas [7], this will again have led to an underestimation of the proportion of ill-defined causes of death in these countries. Whether this may also have had an impact on our results for educational inequalities is, however, difficult to assess.

Second, people with unknown education were excluded from the analyses. The share of ill-defined causes of death was higher among people with unknown education compared with those with primary education. However, due to the small percentage of unknown education in the mortality datasets, our conclusions do not change when combining unknown education with primary education (results not shown).

Third, some datasets had a cross-sectional unlinked design, whereas other consisted of census-linked mortality follow-up studies. It has been shown that mortality inequalities based on unlinked datasets are likely to suffer from the numerator-denominator bias [13, 22], observed when information on education comes from death certificates for the deceased (the numerator), and from census for the population (the denominator) [23]. Education misreporting has been found larger for deaths from ill-defined conditions [22]. This could spuriously produce inequalities in mortality from ill-defined conditions in countries with cross-sectional unlinked designs. Although all four countries showed statistically significant results, only Poland had an exceptionally high proportion of ill-defined causes of death, which has been reported previously [7, 24].

Forth, there is a large variation in sample sizes between European countries. This might have affected the power to clearly detect differences in the proportion of ill-defined causes of death by educational level. In some countries, these differences were statistically significant probably due to the extremely small number of cases in one of the three educational categories. The variations in sample sizes might have also affected differences observed between men and women. Whereas socioeconomic differences in the proportion of ill-defined causes of death were found in about half of the countries among men, these differences were detected only in two countries among women. These gender differences may be, at least partly, due to the differences in sample sizes as the number of deaths was much lower among women than among men.

As mentioned in the introduction, ill-defined causes of death may hide important well-defined causes of death. Autopsy may play an important role in order to identify the correct well-defined cause of death. It has been reported in Barcelona that after forensic tests only 28% of ill-defined causes of death remained ill-defined, the rest being redistributed in other specific causes of death, mainly diseases of circulatory system and to a lesser extent suicide [25]. The percentage of autopsies varies considerably between European countries. In 2000s, this percentage conducted was less than 10% in Norway, Denmark, Netherlands and Switzerland, about 15% in Sweden, and 30% or more in Finland, Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Lithuania and Estonia, and not available in Belgium, France, UK, Spain, Italy and Poland [24]. Our findings suggest that the lower the percentage of autopsies the higher the proportion of ill-defined causes of death. Except Poland, for which we do not have information about the autopsy rate, Norway, Denmark, Netherlands and Switzerland are countries with the lowest autopsy rate in Europe but with one of the highest percentages of ill-defined causes of death. This negative correlation between the autopsy rate and the proportion of ill-defined causes of death has been reported previously [26].

The literature suggests that IHD [27, 28] or suicide [11, 29] may be misclassified as ill-defined causes of death. IHD could be misclassified because deaths from myocardial infarctions may occur suddenly, and when due to cardiac arrhythmia are not detectable even with autopsy. Suicide could be misclassified due to religious taboos, cultural norms and social stigma or due to lack of evidence [30].

Conclusions

We found educational differences in the proportion of ill-defined causes of death in several European countries. However the percentage difference was not large enough to impact educational inequalities in well-defined causes of death after a redistribution of ill-defined causes of death. In other words, if the proportion of ill-defined conditions remains small, any redistribution of these causes of death will have only a negligible impact on socioeconomic inequalities in well-defined causes of death. This highlights the importance of keeping the proportion of ill-defined causes of death in the national mortality statistics at a possible minimum if we want to get meaningful statistics from cause of death data. Although there may be other forms of misclassification, our results suggest that findings from previous studies documenting socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific mortality in Europe are not likely to be biased by differences in the quality of cause-of-death information.

References

Huisman M, Kunst AE, Bopp M, Borgan JK, Borrell C, Costa G, Deboosere P, Gadeyne S, Glickman M, Marinacci C, Minder C, Regidor E, Valkonen T, Mackenbach JP: Educational inequalities in cause-specific mortality in middle-aged and older men and women in eight western European populations. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9458): 493-500. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17867-2.

Kulik MC, Menvielle G, Eikemo TA, Bopp M, Jasilionis D, Kulhánová I, Leinsalu M, Martikainen P, Östergren O, Mackenbach JP, for the EURO-GBD-SE Consortium: Educational inequalities in three smoking-related causes of death in 18 European populations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014, 16 (5): 507-518. 10.1093/ntr/ntt175.

Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam A-JR, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, Leinsalu M, Kunst AE: Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health in 22 European Countries. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358 (23): 2468-2481. 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519.

Menvielle G, Kunst AE, Stirbu I, Strand BH, Borrell C, Regidor E, Leclerc A, Esnaola S, Bopp M, Lundberg O, Artnik B, Costa G, Deboosere P, Martikainen P, Mackenbach JP: Educational differences in cancer mortality among women and men: a gender pattern that differs across Europe. Br J Cancer. 2008, 98 (5): 1012-1019. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604274.

Franca E, Campos D, Guimaraes MD, Souza Mde F: Use of verbal autopsy in a national health information system: Effects of the investigation of ill-defined causes of death on proportional mortality due to injury in small municipalities in Brazil. Popul Health Metr. 2011, 9: 39-10.1186/1478-7954-9-39.

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ: Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006, 367 (9524): 1747-1757. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9.

Mathers CD, Fat DM, Inoue M, Rao C, Lopez AD: Counting the dead and what they died from: an assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bull World Health Organ. 2005, 83 (3): 171-177.

Ruzicka LT, Lopez AD: The use of cause-of-death statistics for health situation assessment: national and international experiences. World Health Stat Q. 1990, 43 (4): 249-258.

Becker TM, Wiggins CL, Key CR, Samet JM: Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions: a leading cause of death among minorities. Am J Epidemiol. 1990, 131 (4): 664-668.

D'Amico M, Agozzino E, Biagino A, Simonetti A, Marinelli P: Ill-defined and multiple causes on death certificates – A study of misclassification in mortality statistics. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999, 15 (2): 141-148. 10.1023/A:1007570405888.

Ohberg A, Lonnqvist J: Suicides hidden among undetermined deaths. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998, 98 (3): 214-218. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10069.x.

Marchand JL, Imbernon E, Goldberg M: Causes of death in a cohort of EDF-GDF employees: comparison between occupational medicine and official statistics data. Causes de deces dans une cohorte de travailleurs EDF-GDF: comparaison des donnees de la medecine du travail et de la statistique nationale. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2003, 51 (5): 469-480.

Jasilionis D, Stankuniene V, Ambrozaitiene D, Jdanov DA, Shkolnikov VM: Ethnic mortality differentials in Lithuania: contradictory evidence from census-linked and unlinked mortality estimates. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012, 66 (6): e7-10.1136/jech.2011.133967.

Andreev E, Pridemore WA, Shkolnikov VM, Antonova OI: An investigation of the growing number of deaths of unidentified people in Russia. Eur J Public Health. 2008, 18 (3): 252-257. 10.1093/eurpub/ckm124.

Reijneveld SA: Causes of death contributing to urban socioeconomic mortality differences in Amsterdam. Int J Epidemiol. 1995, 24 (4): 740-749. 10.1093/ije/24.4.740.

Ev D, Koolman X, Jones AM: Explaining income-related inequalities in doctor utilisation in Europe. Health Econ. 2004, 13 (7): 629-647. 10.1002/hec.919.

Lostao L, Regidor E, Geyer S, Aiach P: Patient cost sharing and social inequalities in access to health care in three western European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 65 (2): 367-376. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.001.

Menvielle G, Jellouli F: Building a harmonized database on health inequalities in the European Union. The potential for reduction of heatlh inequalities in Europe The EURO-GBD-SE Final Report. Edited by: Eikemo TA, Mackenbach JP. 2012, Rotterdam: Department of Public Health, Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam, Available at: http://www.euro-gbd-se.eu/fileadmin/euro-gbd-se/public-files/EURO-GBD-SE_Final_report.pdf

Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inoue M: Age Standardization of Rates: A New WHO Standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series: No. 31. 2001, Geneva: World Health Organization

Sheskin DJ: Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statistical procedures. 2004, Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 3

Garssen J, Bos V, Kunst AE, van der Meulen A: Sterftekansen en doodsoorzaken van niet-westerse allochtonen. [Differential mortality risks and causes of death among non-western foreigners in the Netherlands]. Bevolkingstrends. 2003, 51 (3): 12-27.

Shkolnikov VM, Jasilionis D, Andreev EM, Jdanov DA, Stankuniene V, Ambrozaitiene D: Linked versus unlinked estimates of mortality and length of life by education and marital status: evidence from the first record linkage study in Lithuania. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 64 (7): 1392-1406. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.014.

Kunst AE, Groenhof F, Borgan JK, Costa G, Desplanques G, Faggiano F, Hemström O, Martikainen P, Vågerö D, Valkonen T, Mackenbach JP: Socio-economic inequalities in mortality. Methodological problems illustrated with three examples from Europe. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1998, 46 (6): 467-479.

European Health for All Database. Accessed in March 2014 from http://www.euro.who.int/hfadb

Gotsens M, Mari-Dell'Olmo M, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Martos D, Espelt A, Perez G, Perez K, Teresa Brugal M, Barberia Marcalain E, Borrell C: Validacion de la causa basica de defuncion en las muertes que requieren intervencion medicolegal. [Validation of the underlying cause of death in medicolegal deaths]. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2011, 85 (2): 163-174. 10.1590/S1135-57272011000200005.

Ylijoki-Sorensen S, Sajantila A, Lalu K, Boggild H, Boldsen JL, Boel LW: Coding ill-defined and unknown cause of death is 13 times more frequent in Denmark than in Finland. Forensic Sci Int. 2014, 244C: 289-294.

Armstrong DL, Wing SB, Tyroler HA: United States mortality from ill-defined causes, 1968–1988: potential effects on heart disease mortality trends. Int J Epidemiol. 1995, 24 (3): 522-527. 10.1093/ije/24.3.522.

Lozano R, Murray CJL, Lopez AD, Satoh T: Miscoding and misclassification of ischaemic heart disease mortality. Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy Working Paper No. 12. 2001, Geneva: World Health Organization

Kapusta ND, Tran US, Rockett IR, De Leo D, Naylor CP, Niederkrotenthaler T, Voracek M, Etzersdorfer E, Sonneck G: Declining autopsy rates and suicide misclassification: a cross-national analysis of 35 countries. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011, 68 (10): 1050-1057. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.66.

Rockett IR, Wang S, Stack S, De Leo D, Frost JL, Ducatman AM, Walker RL, Kapusta ND: Race/ethnicity and potential suicide misclassification: window on a minority suicide paradox?. BMC Psychiatry. 2010, 10: 35-10.1186/1471-244X-10-35.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/1295/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Caspar Looman for his statistical advice.

We thank the EURO-GBD-SE international project partners who supplied the mortality data: Annibale Biggeri (Tuscany, Italy), Matthias Bopp (Switzerland), Carme Borrell (Barcelona, Spain), Lynsey Brown (England and Wales), Giuseppe Costa (Turin, Italy), Patrick Deboosere (Belgium), Santiago Esnaola (Basque Country, Spain), Johannes Klotz (Austria), Katalin Kovács (Hungary), Anita Lange (Denmark), Mall Leinsalu (Estonia), Olle Lundberg (Sweden), Pekka Martikainen (Finland), Gwenn Menvielle (France), Enrique Regidor (Madrid, Spain), Maica Rodríguez-Sanz (Barcelona, Spain), Jitka Rychtaříková (Czech Republic), Bjørn Heine Strand (Norway), Chris White (England and Wales), Bogdan Wojtyniak (Poland).

Funding

This work was supported by the Public Health Programme of the European Commission (grant number 20081309) and by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, project number 121020026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

IK, GM and JPM conceived the study. IK performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript. GM, MB, CB, PD, ML, PM, ER, MRS, JR, BW contributed to data acquisition. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kulhánová, I., Menvielle, G., Bopp, M. et al. Socioeconomic differences in the use of ill-defined causes of death in 16 European countries. BMC Public Health 14, 1295 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1295

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1295