Abstract

Background

At least one-third of women in India experience intimate partner violence (IPV) at some point in adulthood. Our objectives were to describe the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy and after delivery in an urban slum setting, to review its social determinants, and to explore its effects on maternal and newborn health.

Methods

We did a cross-sectional study nested within the data collection system for a concurrent trial. Through urban community surveillance, we identified births in 48 slum areas and interviewed mothers ~6 weeks later. After collecting information on demographic characteristics, socioeconomic indicators, and maternal and newborn care, we asked their opinions on the justifiability of IPV and on their experience of it in the last 12 months.

Results

Of 2139 respondents, 35% (748) said that violence was justifiable if a woman disrespected her in-laws or argued with her husband, failed to provide good food, housework and childcare, or went out without permission. 318 (15%, 95% CI 13, 16%) reported IPV in the year that included pregnancy and the postpartum period. Physical IPV was reported by 247 (12%, 95% CI 10, 13%), sexual IPV by 35 (2%, 95% CI 1, 2%), and emotional IPV by 167 (8%, 95% CI 7, 9). 219 (69%) women said that the likelihood of IPV was either unaffected by or increased during maternity. IPV was more likely to be reported by women from poorer families and when husbands used alcohol. Although 18% of women who had suffered physical IPV sought clinical care for their injuries, seeking help from organizations outside the family to address IPV itself was rare. Women who reported IPV were more likely to have reported illness during pregnancy and use of modern methods of family planning. They were more than twice as likely to say that there were situations in which violence was justifiable (odds ratio 2.6, 95% CI 1.7, 3.4).

Conclusions

One in seven women suffered IPV during or shortly after pregnancy. The elements of the violent milieu are mutually reinforcing and need to be taken into account collectively in responding to both individual cases and framing public health initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A violation of human rights with health and development impacts [1], violence against women is a global public health concern [2]. Intimate partner violence (IPV), defined as “behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including acts of physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviours” [3, 4], is suffered by between 15% and 71% of women at some point in their lives [3].

IPV in India

Although population-based surveys underline the ubiquity of IPV, its occurrence and impacts are frequently hidden and the figures are usually underestimates [5]. India’s third National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3 2005–2006) suggested that 33% of ever-married women aged 15–49 years had faced IPV at some point over the age of 15 [6]. A second large cross-sectional survey involving over 14 000 women in 18 states yielded an estimate of 39% [7]. Other community-based surveys suggest a prevalence of physical IPV of 35-60% [8–10].

IPV in urban India

A secondary analysis of NFHS-3 data suggested that 28% of ever-married urban women aged 15–49 years had experienced physical violence in the last year [11]. There is less information on IPV in the slums that characterize India’s cities. The NFHS-3 estimated the lifetime prevalence against ever-married women at 23% in Mumbai’s slum population [6]. The figure was 54% in a Kolkata slum [12]. Over shorter recall periods, 37% of women in a Mumbai slum survey reported violence in the preceding year (verbal 32%, physical 23%, and sexual 9%) [13], compared with 62% in Pune [14], 17% in Kolkata [15], and 27% in Bangalore in the preceding six months [16].

IPV during maternity

Pregnancy does not protect women from IPV [17–19]. A global systematic review described a prevalence during pregnancy of 1-20% [20], a review of studies in Asian countries 4-48% [21], and a review of Indian studies 21-28% [22].

Consequences of IPV during maternity

IPV leads to both acute injuries and profound longer-term challenges to health and wellbeing [23, 24]. Studies from India suggest that women who experience physical IPV during pregnancy are more likely to suffer depression and mental ill-health [25]. They are more likely to miscarry, have premature labor [26], and deliver low birth weight infants [27, 28]. The survival of their infants is reduced in the perinatal [29, 30], neonatal [29, 31], infant [32], and childhood periods [33]. Women who report IPV are also less likely to have prenatal care [34, 35], may be more likely to terminate pregnancy [36], and are at greater risk of sexually transmitted infection [37, 38].

Risk factors for IPV

Figure 1 categorizes factors available in our dataset that have been described as potential determinants of IPV in India and included in recent reviews [35, 39]. Each level interacts with others. For example, improvements in women’s education may lead to changes in societal attitudes to IPV, and have a bearing on employment and socioeconomic status. At community level, IPV appears to be less common in urban than in rural environments [11, 40]. Although it is difficult to quantify, several studies have suggested that an absence of social support might make women more vulnerable to IPV [10, 41, 42].

At the household level, there is a consensus that poverty increases the risk of IPV. This is seen in Indian studies of IPV in general [10, 43–48], in pregnancy [7, 11], and in slum communities [12, 15]. IPV has been described as more likely to be experienced by women from lower castes [43], larger families, and certain faith groups [7, 11, 18, 49]. There is some evidence that women who have witnessed abuse in their families are more likely to experience it themselves [10, 45].

Having more educated partners appears to protect women against IPV [42, 50]. The same is true of employment, in that women whose partners are in work are less likely to suffer IPV. Spousal alcohol or drug use is a risk factor in many studies [10, 41–43, 47, 51, 52], including those that consider IPV in pregnancy [7, 11, 13], and in slum communities [12, 15]. Risk-taking behavior such as spousal gambling [7] and extramarital sex increase the risk of IPV [15, 53].

Women who marry younger (under 18 years in most studies) are at greater risk of IPV [11, 54–56], although this finding is not always replicated [57] and older women are also at increased risk [13, 46, 47]. Longer marriages may be associated with increased [15] or decreased risk [7]. As with their partners, women with less education are at greater risk of IPV [7, 11, 13, 18, 27, 45–47, 50, 54]. It has been suggested that women who are more educated than their husbands are at greater risk [50], but this has not been substantiated and a recent study found the opposite [58]. The effects of other risk factors are unclear, particular examples in the Indian context being son preference and women’s employment. We discuss these later.

SNEHA (Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action) is a non-government organization working to improve the health of women and children in Mumbai’s disadvantaged settlements, in four domains: prevention of violence against women and children, reproductive health, maternal and newborn health, and childhood nutrition. We offer a range of counseling, legal, and liaison services for women and children experiencing violence. Despite our work in the area for over a decade, we had little information on the prevalence of IPV within slum communities. We had also become concerned about the impact of IPV on women’s experience of maternity. During a community-based program that focused on maternal and newborn health [59], we interviewed women after childbirth. We included a series of questions about violence within a larger questionnaire. Our objectives were to describe the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy and postpartum in an urban slum setting, to review potential risk factors in the urban context, and to explore its effects on maternal and newborn health.

Methods

Setting

The capital of Maharashtra state, Mumbai has 12.4 million residents. Although 63% of households fall into India’s highest wealth quintile [6], 53% of residents live in slums [60]. Indicators of women’s status such as literacy, workforce participation, age at marriage, and healthcare seeking tend to be better than the national averages. We used data collected during a cluster randomized controlled trial of community mobilization to improve maternal and newborn health [59, 61]. The trial involved 48 slum clusters, each of ~1200 households, covering a population of ~283 000. 26% of homes were of insubstantial fabric (corrugated iron, planking, tarpaulin) and sizeable proportions did not have metered electricity (28%), access to individual or communal piped water (21%), or individual toilet facilities (94%). More than one-third of clusters were adjacent to hazards such as railway lines, garbage dumps and polluted bodies of water.

Data collection

A registration system monitored live births, stillbirths, maternal and neonatal deaths in all 48 slum clusters. Births were identified by 99 locally resident women, covering ~600 households each. After confirming a birth, one of 12 researchers visited mothers 6 weeks later for a postnatal interview. The interview included questions on demographic characteristics, socioeconomic indicators, maternal and newborn care, and was framed as a women’s health study with a particular focus on maternal and newborn health. After an explanation of the data collection activities, participants were asked for verbal consent to interview and were assured of data confidentiality. Completed interviews were checked by supervisors and project officers, both systematically and through random visits, and were entered in a database in Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corporation). Information provided by the participants remained confidential and no analyses or outputs included their names. Access to data was restricted to the analysts and was password protected.

Because information on the epidemiology of IPV is limited, particularly at disaggregated urban levels, we added a module to the routine questionnaire. All women who gave birth from March to September 2009 and consented to interview received the module, which included questions about justifications for IPV, instances of physical, emotional, or sexual IPV in the preceding year, injuries, help seeking, and spousal drug and alcohol use. The questions were adapted from existing versions in the Demographic and Health Surveys [6].

We followed World Health Organization ethical and safety recommendations [62]. Participants were told that the study was about maternal and newborn health, and that women in the study area who had given birth in a certain period would be approached for interview. During the interview, participants were informed of the nature and potential sensitivity of the IPV module and consent was taken before administering it. One woman per household received the module. Most of the interviews were conducted in participants’ homes. The researchers made efforts to interview women alone, but the density of slum homes and a desire to make respondents comfortable meant that there were limits to their ability to achieve privacy. At the first visit, if family members were present and the researcher was concerned about privacy, she asked the respondent for a suitable time to make a second visit. If family members were present again, information about the maternal and newborn health study was shared with them. The researcher told them that some questions might be embarrassing for the participant to answer in the presence of others. The interview began with the routine questionnaire and, when family members were reluctant to leave, the researcher encouraged them to stay for a while to reassure themselves about the nature of the questions. Most family members were generally amenable to leaving before the IPV module. The researchers carried a resource list of support services near the study area. They visited providers and informed them about the study, and that their help might be needed. All participants received information on resources, irrespective of whether or not they reported violence. They were told that the information could help them to support other women if they suffered violence, and referral was arranged if requested.

Given available estimates of the prevalence of IPV, a sample size of 1800 would give an estimated proportion with a precision of 5% at a confidence level of 95%. Recruitment was planned to be sequential until 300 questionnaires had been collected in each of the six municipal wards across which the 48 clusters were distributed. We assumed a high attrition rate because of the sensitive nature of the questions, and interviewed more women than the required sample size.

Variables

We defined physical IPV according to the WHO Multi-Country Study [63], as an instance in which her partner beat, punched, kicked, dragged, or slapped a woman, twisted her arm, pulled her hair, hit her with an object, choked, burned, or physically restrained her. Emotional IPV was defined as an instance in which a spouse showed jealousy, humiliated his partner in front of others, accused her of infidelity, threatened to evict her or actually did so, threatened her or her children with violence, or forcibly took something from her. Sexual IPV was defined as an instance in which a woman was forced to have sex with her partner when she did not want to. Respondents were asked the questions about IPV in the preceding year. The timing of the interview meant that the preceding year encompassed less than two months before the pregnancy, pregnancy itself, and the postpartum period. For each type of IPV, a subsidiary question on frequency followed (once, sometimes, often). We also asked respondents who reported physical IPV whether it had happened more before, during or after pregnancy. We asked about injuries or complications that might have resulted from it (cuts, bruises, pain, burns, wounds, fractures and dental trauma, fetal death, premature labour, vaginal bleeding), and whether it led to problems (self-care, infant care) such as prevention of breastfeeding. We asked whether respondents had sought help from family members, friends or neighbours, local or religious bodies, women’s or other non-government organizations, doctors, the police, lawyers or a helpline.

Socioeconomic status was described by asset scores assigned to respondents on the basis of standardized weights for the first component of a principal components analysis, ordered and divided into quintiles [64, 65]. Assets included a range of consumer durables and house ownership and construction. The remaining variables included miscarriage (cessation of pregnancy before 22 completed weeks) in a previous pregnancy, any reported illness during the index pregnancy, receipt of any prenatal care, home delivery, preterm delivery before 37 completed weeks of gestation, low birth weight (< 2500 g), infant sex, and use of a modern family planning method in the three years preceding the index pregnancy (oral contraceptive pill, condoms, intrauterine device, injectable or implantable contraception).

Statistical analysis

We summarized responses to questions about IPV with frequencies and percentages, categorized according to type of IPV. Analysis of determinants followed the conceptual framework in Figure 1. We hypothesized that the odds of IPV during maternity would decrease with rising socioeconomic status, woman’s age, age at marriage, parity, and education, and with her husband’s education and employment; would increase if her husband used alcohol or drugs; and would be affected in an unspecified direction by family structure and religion. We entered IPV as a binary dependent variable in multivariable logistic regression models with a random effect for cluster. Hypothetical determinants were entered as independent variables in both univariable and multivariable models [66]. At household level, socioeconomic quintile, family unit, and religion were entered as categorical indicator variables. At woman level, age-group, schooling, age-group at marriage, and parity were entered as categorical indicator variables, and employment as a binary variable. At partner level, husband’s schooling was entered as a categorical indicator variable, and employment and alcohol use as binary variables. We did not expect the intervention under test in the trial in which the study was nested to affect IPV. Including a covariate for allocation in the analysis made no substantial difference to the findings, and it has not been included in the analyses presented.

In an additional analysis, we hypothesized that having a female baby might increase the odds of IPV, during pregnancy if the infant sex was known, or postpartum. We therefore added an independent variable for infant sex to a model including the covariates already mentioned. We also hypothesized that IPV might be more likely to occur in an environment in which a woman had had a previous miscarriage. Again, we added an independent miscarriage variable to the existing model.

Exploratory analyses examined whether IPV was a potential determinant of a series of outcomes. First, we hypothesized that IPV would increase the odds of illness during the index pregnancy, preterm birth, low birth weight and home delivery, and that it would reduce the odds of prenatal care. Second, we hypothesized that women who reported IPV would be more likely to justify it. Third, we hypothesized that women who reported IPV would be less likely to have used modern methods of family planning in the preceding three years. We entered each of these as a binary dependent variable, IPV as an independent variable, and included covariates shown to be associated (at p < 0.1) in the analysis summarized in Table 1: socioeconomic quintile, religion, maternal age (forced into the model in view of its intuitive importance) and employment, and husband’s alcohol use. Analyses were done in Stata 12 (College Station, TX) and presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Ethical approval

Data for the study originated from a larger process of data collection approved by the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai and the Independent Ethics Committee for Research on Human Subjects (Mumbai committee, reference IEC/06/31).

Results

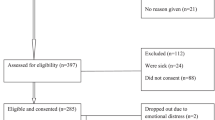

Data were provided by 2591 women over 9 months in 2009. Interviews were not achieved in 452 cases (17%), in which women consented to and completed the questionnaire on maternal and newborn health, but withdrew from the IPV module either before or shortly after it began. Lack of privacy played a part in this (310, 12%). There were no appreciable differences in socioeconomic status, education, or age between respondents and non-respondents. The analysis was based on information provided by 2139 women.

Table 1 summarizes responses to the question, “Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations?” Over one-third of respondents felt that IPV was justifiable in some situation (768, 36%), including 748 (35%) who said that it would be justified if a woman disrespected her in-laws or argued with her husband, failed to provide good food, housework and childcare, or went out without his knowledge. Overall, 318 (15%, 95% CI 13, 16%) women reported facing IPV in the year that included pregnancy and the postpartum period (Table 2). Physical IPV was reported by 247 (12%, 95% CI 10, 13%), and coercive sex by 35 (2%, 95% CI 1, 2%). Emotional violence was reported by 167 women (8%, 95% CI 7, 9). Slaps, kicks and punches were the most common forms of physical violence.

Table 3 shows that about one-third of women said that IPV reduced during pregnancy and the postpartum period, but that 69% said that it either remained at the same level or increased. When asked if IPV was more likely when spouses had been drinking alcohol, 58/149 (39%) women said that it was. Help-seeking to stop IPV was limited (15%) and mostly within the natal family (13%). No women had sought help from a friend or neighbour, religious leader, doctor, lawyer or helpline; 5 had involved the police. Half of women who reported physical IPV in the last year said that it happened sometimes or often. The commonest physical sequelae were pain, cuts and bruises, and a few women reported complications such as vaginal bleeding or early labour. Medical treatment was needed by about one-fifth of women who reported physical IPV. Some said that their ability to care for themselves (17%) or their baby (8%) had been compromised.

Table 4 compares the profiles of women who reported emotional, physical or sexual IPV with those who did not. In multivariable models, the odds of IPV were greater for women living in poorer families, the prevalence reaching 28% in the poorest quintile. Greater odds were seen in Muslim families, women in paid employment, and women whose husbands used alcohol. There was no evidence that having a female baby affected the risk of IPV (aOR 1.07; 95% CI 0.82, 1.39). However, in both univariable and multivariable models, women who reported a previous miscarriage were more likely to have reported IPV in the recent pregnancy (aOR 1.76; 95% CI 1.20, 2.58).

Table 5 summarizes the findings on IPV as a potential determinant of health problems related to pregnancy. Women who reported IPV in the study were more likely to have reported illness during the index pregnancy and use of modern methods of family planning in the preceding 3 years. We speculated that IPV might be associated with parous women having not yet provided a son, or with a substantial age difference or difference in education between wife and husband [15]. We tested several scenarios and found no such associations (data not shown). Women who reported IPV were more than twice as likely to have said that it was justifiable in at least one scenario in Table 1.

Discussion

In interviews with over 2000 women living in Mumbai slums, IPV – physical (12%), emotional (8%) or sexual (2%) – was common during and after pregnancy. Although IPV appears to be less common in urban than in rural settings, new evidence suggests that urban women may be at higher risk after adjustment for socioeconomic status [11]. IPV was more likely to be reported by women in poorer families, Muslim homes, and those whose husbands used alcohol. Although 18% of women who had suffered physical IPV sought clinical care for their injuries, seeking help from organizations outside the family to address IPV itself was rare [14].

Limits to the study included self-report – important given the risk of adverse consequences – and the fact that we used a module within a longer questionnaire administered by researchers who, though trained and a familiar presence within the study areas, were not themselves counselors. They were trained by IPV counselors, were female, and had been interviewing mothers since October 2005. The module on IPV followed less disquieting modules on demography and maternal and newborn care. It was based on modules used in other large surveys, but involved a recall period of up to a year and the questions were relatively closed.

At 15%, reported IPV during maternity accords with other studies from India. Domestic violence during pregnancy (which includes but is not limited to IPV) was described by 18% of respondents in surveys in Uttar Pradesh state in the mid-1990s [29], 21% in a postnatal sample at a Delhi hospital [27], and 28% in pregnant women admitted to hospital in Chandigarh [42]. A large study from Bhopal reported domestic violence in 13% of pregnancies [41], and a multisite study described figures of 26% for physical, 22% for sexual and 63% for psychological violence during pregnancy [26]. The figure of 15% is almost certainly an underestimate: information was incomplete for 17% of the sample, and underreporting is usual in surveys. In some cases, women wanted to share information, but family members were unwilling to ensure privacy in spite of repeated requests by the investigators.

Reports of emotional and sexual IPV were relatively uncommon. We used definitions based on questions comparable with other studies, nested in comparable types of interview. There are two (not mutually exclusive) possibilities for the lower frequencies: that they were underreported or that they were true findings. Achieving participation, confidentiality and disclosure of IPV may have been especially difficult in this study. Mumbai’s slum homes are small, and the practice of confinement to the home in the postpartum period limited the researchers’ likelihood of achieving interviews outside. The second possibility is that rates of emotional and sexual IPV may actually be lower in Mumbai’s poorer communities than in rural settings and some other cities, and during pregnancy and postpartum. To address both these possibilities, we are incorporating service provision for women experiencing IPV within an initiative that integrates multiple activities for women’s and children’s health. The continuous presence of fieldworkers, peer-activists, and counselors in the community allows us to identify IPV prospectively and we hope will contribute to a clearer understanding of its frequency.

In adjusted models, IPV during maternity was more likely in conditions of poverty, Muslim faith, women’s paid employment, and spousal alcohol use. The association with poverty was expected [8, 11, 12, 15, 46, 54]. As a determinant, faith is more difficult to interpret, but has been noted before [11, 27]. Muslim families in Mumbai’s slums are relatively worse-off and it is possible that the increased risk of IPV reflects residual confounding within a matrix of poverty [48, 67].

The finding that women who were employed were more likely to have reported IPV is supported by studies across a range of locations in India [10, 11, 16, 43, 68]. It has not been replicated in all studies [42]: a small sample in a Kolkata slum suggested that unemployment was a risk factor [12]. Some authors have suggested that women’s work represents a challenge to the patriarchal structure that might provoke spousal violence [11, 48, 49]. However, employment may be an effect rather than a cause, a means of survival rather than a manifestation of empowerment. A woman may be more likely to seek work if her family is poor, her home environment unstable, and her husband drinks or is having extramarital sex [15, 53]. A large study in 18 Indian states suggested that, while working women were at higher risk of IPV, women engaged in unskilled labour were most at risk [7]; and a study from Mysore suggested that, although women with jobs were more likely to suffer IPV than women without jobs, those with skilled occupations were at lower risk [69]. Chibber and colleagues suggest that women who contribute to household income are at greater risk than non-contributors, but women who are solely responsible for household income are at lower risk [49]. Perhaps stability and reliability within relationships are important. When women have more resources in terms of land and assets, IPV seems to be less common [16, 54]. A study involving 744 married women in Bangalore slums suggested that the risk of IPV increased if unemployed women became employed, or if their husbands lost their jobs [70]. It also suggested that violence was more common in love marriages, women who worked before and after marriage, and participants in social and vocational groups. Because of social structures in India, it is possible that love marriages are more likely to be accompanied by financial adversity and involve emotional strain.

Spousal alcohol use is a determinant of IPV [10–13, 15, 41, 42, 51, 71]. We did not see increased odds of IPV in older or less educated women, or in those who had married younger, which have been described [11, 13, 55, 56]. We speculated that the risk of IPV might be higher if there were substantial differences in education or age between husband and wife [11, 12, 50, 58], but we saw no evidence for this in subsidiary analyses.

Although spousal drunkenness, suspected infidelity, unwillingness to have sex, and dowry were not now seen as justifiable triggers, one-third of women felt that violence was a justifiable response to what might be described as a failure to live up to the role of wife and mother within her husband’s family. This finding echoes those of Jejeebhoy in rural Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu [54]. However, a recent analysis of the NFHS-3 found that women who justified partner violence were less likely to suffer it. The authors suggest that this might reflect submissive avoidance [11]. We found the opposite: that women who reported IPV were more than twice as likely to say that there were situations in which it was justifiable. Whether this represented self-protective rationalization or was part of the causal matrix is unclear. There is also some evidence that justification is associated with less likelihood of care-seeking for illness. For example an analysis of NFHS-3 data from Uttar Pradesh suggested that women who accepted any justification of violence were less likely to seek care for sexually transmitted infections [38].

IPV during pregnancy has implications for the health and wellbeing of mothers and fetuses, and with less likelihood of prenatal care and care for intercurrent problems [26, 34]. Studies have found that physical IPV in pregnancy increases the likelihood of miscarriage or low birth weight [31, 72–76]. Again, we are unsure about the cause structure. One could sketch a pathway from IPV to compromised fetal growth and miscarriage. Equally, one could propose that the association is residually confounded by the socioeconomic and cultural milieu, so that poor outcomes are corollaries of IPV but not caused by it. For example, miscarriage may be the result of IPV, but may also add to family stress and make subsequent violence more likely. IPV during pregnancy may lead to illness (early labour and vaginal bleeding were mentioned by respondents), but concerns about IPV might also increase the likelihood that a woman will report illness when asked about it in an interview. Ackerson and Subramanian found a strong association between IPV and increased child mortality rates, and suggested that violence impaired women’s ability to take care of their children and caused psychological stress in the children themselves [32]. Some of our respondents reported difficulty in taking care of themselves during pregnancy and difficulty in caring for their babies.

Unwanted pregnancies and the number of living children have been associated with IPV in several studies [32, 77–80]. The increased likelihood of family planning in women who reported IPV is counterintuitive, since it is a lack of control over women’s reproductive health choices that has been discussed previously [80, 81]. It is just possible that women are making choices to limit conception in a stressful situation, but we emphasize that we have no evidence for this intriguing speculation.

Conclusions

Intimate partner violence against women during maternity was unacceptably common in Mumbai’s slums. One in seven women suffered violence during or shortly after pregnancy. IPV begins in a culture that condones it – indeed, justifies it - and is abetted by poverty and alcohol use. The elements of the violent milieu are mutually reinforcing and need to be taken into account collectively in responding to both individual cases and framing public health initiatives.

References

UN Millennium Project: Taking action: achieving gender equality and empowering women. 2005, New York: Task force on education and gender equality

WHO: World report on violence and health. 2002, Geneva: World Health Organization

Heise L, Garcia-Moreno C: World report on violence and health. Violence by intimate partners. 2002, Geneva: World Health Organization

Jewkes R, Sen P, Garcia-Moreno C: Sexual violence. World report on violence and health. Edited by: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R. 2002, Geneva: World Health Organization, 149-181.

WHO: London school of hygiene and tropical medicine: preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. 2010, Geneva: World Health Organization

Government of India Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: National family health survey, India (NFHS-3 2005–06). 2007, Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences

Mahapatro M, Gupta R, Gupta V: The risk factor of domestic violence in India. Indian J Community Med. 2012, 37: 153-157. 10.4103/0970-0218.99912.

INCLEN: Domestic violence in India: a summary report of a multi-site household survey. 2000, Washington DC: International Clinical Epidemiologists’ Network, International Center for Research on Women

Khot A, Menon S, Dilip T: Domestic violence: levels, correlates, causes, impact, and response. A community based study of married women from Mumbai slums. 2004, Mumbai: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes

Jeyaseelan L, Kumar S, Neelakantan N, Peedicayil A, Pillai R, Duvvury N: Physical spousal violence against women in India: some risk factors. J Biosoc Sci. 2007, 39: 657-670. 10.1017/S0021932007001836.

Kimuna SR, Djamba YK, Ciciurkaite G, Cherukuri S: Domestic violence in India: insights from the 2005–2006 national family health survey. J Interpers Violence. 2013, 28: 773-807. 10.1177/0886260512455867.

Sinha A, Mallik S, Sanyal D, Dasgupta S, Pal D, Mukherjee A: Domestic violence among ever married women of reproductive age group in a slum area of Kolkata. Indian J Public Health. 2012, 56: 31-36. 10.4103/0019-557X.96955.

Shrivastava PS, Shrivastava SR: A study of spousal domestic violence in an urban slum of Mumbai. Int J Prev Med. 2013, 4: 27-32.

Ruikar MM, Pratinidhi AK: Physical wife abuse in an urban slum of Pune, Maharashtra. Ind J Public Health. 2008, 52: 215-217.

Pandey GK, Dutt D, Banerjee B: Partner and relationship factors in domestic violence: perspectives of women from a slum in Calcutta, India. J Interpers Violence. 2009, 24: 1175-1191. 10.1177/0886260508322186.

Rocca CH, Rathod S, Falle T, Pande RP, Krishnan S: Challenging assumptions about women’s empowerment: social and economic resources and domestic violence among young married women in urban South India. Int J Epidemiol. 2009, 38: 577-585. 10.1093/ije/dyn226.

Stewart DE, Cecutti A: Physical abuse in pregnancy. CMAJ. 1993, 149: 1257-1263.

Purwar MB, Jeyaseelan L, Varhadpande U, Motghare V, Pimplakute S: Survey of physical abuse during pregnancy GMCH, Nagpur, India. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 1999, 25: 165-171. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1999.tb01142.x.

Jain D, Sanon S, Sadowski L, Hunter W: Violence against women in India: evidence from rural Maharashtra. Rural Remote Health. 2004, 4: 304-

Gazmararian JA, Lazorick S, Spitz AM, Ballard TJ, Saltzman LE, Marks JS: Prevalence of violence against pregnant women. JAMA. 1996, 275: 1915-1920. 10.1001/jama.1996.03530480057041.

Kashif M, Murtaza K, Kirkman M: Violence against women during pregnancy in some Asian countries: a review of the literature. Ital J Public Health. 2010, 7: 6-11.

Campbell J, Garcia-Moreno C, Sharps P: Abuse during pregnancy in industrialized and developing countries. Violence Against Women. 2004, 10: 770-10.1177/1077801204265551.

Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottmoeller M: A global overview of gender based violence. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002, 78 (Suppl 1): S5-S14.

Ludermir AB, Lewis G, Alves Valongueiro S, de Araujo TV B, Araya R: Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010, 376: 903-910. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60887-2.

Patel V, Rodrigues M, Desouza N: Gender, poverty and postnatal depression: a study of new mothers in Goa. Am J Psychiatry. 2002, 159: 43-47. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.43.

Mahapatro M, Gupta RN, Gupta V, Kundu AS: Domestic violence during pregnancy in India. J Interpers Violence. 2011, 26: 2973-2990. 10.1177/0886260510390948.

Muthal-Rathore A, Tripathi R, Arora R: Domestic violence against pregnant women interviewed at a hospital in New Delhi. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2002, 76: 83-85. 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00533-1.

Sarkar NN: The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008, 28: 266-271. 10.1080/01443610802042415.

Ahmed S, Koenig MA, Stephenson R: Effects of domestic violence on perinatal and early-childhood mortality: evidence from north India. Am J Public Health. 2006, 96: 1423-1428. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066316.

Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Acharya R, Barrick L, Ahmed S, Hindin M: Domestic violence and early childhood mortality in rural India: evidence from prospective data. Int J Epidemiol. 2010, 39: 825-833. 10.1093/ije/dyq066.

Jejeebhoy S: Associations between wife-beating and fetal and infant death: impressions from a survey in rural India. Stud Fam Plan. 1998, 29: 300-308. 10.2307/172276.

Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV: Intimate partner violence and death among infants and children in India. Pediatrics. 2009, 124: e878-e889. 10.1542/peds.2009-0524.

Pandey S, Lin Y: Adjusted effects of domestic violence, tobacco use, and indoor Air pollution from use of solid fuel on child mortality. Matern Child Health J. 2012, doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1163-z (Epub ahead of print)

Koski AD, Stephenson R, Koenig MR: Physical violence by partner during pregnancy and use of prenatal care in rural India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011, 29: 245-254.

Sarkar NN: The cause and consequence of domestic violence on pregnant women in India. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013, 33: 250-253. 10.3109/01443615.2012.747493.

Yoshikawa K, Agrawal NR, Poudel KC, Jimba M: A lifetime experience of violence and adverse reproductive outcomes: findings from population surveys in India. Biosci Trends. 2012, 6: 115-121.

Chowdhary N, Patel V: The effect of spousal violence on women’s health: findings from the Stree Arogya Shodh in Goa, India. J Postgrad Med. 2008, 54: 306-312. 10.4103/0022-3859.43514.

Sudha S, Morrison S: Marital violence and women’s reproductive health care in Uttar Pradesh, India. Womens Health Issues. 2011, 21: 214-221. 10.1016/j.whi.2011.01.004.

Santhya KG: Early marriage and sexual and reproductive health vulnerabilities of young women: a synthesis of recent evidence from developing countries. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 23: 334-339. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32834a93d2.

Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV: Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India. Am J Epidemiol. 2008, 167: 1188-1196. 10.1093/aje/kwn049.

Peedicayil A, Sadowski LS, Jeyaseelan L, Shankar V, Jain D, Suresh S, Bangdiwala SI, India SG: Spousal physical violence against women during pregnancy. BJOG. 2004, 111: 682-687. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00151.x.

Khosla AH, Dua D, Devi L, Sud SS: Domestic violence in pregnancy in North Indian women. Indian J Med Sci. 2005, 59: 195-199. 10.4103/0019-5359.16255.

Krishnan S: Gender, caste, and economic inequalities and marital violence in rural South India. Health Care Women Int. 2005, 26: 87-99. 10.1080/07399330490493368.

Koenig M, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy S, Campbell J: Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. Am J Public Health. 2006, 96: 132-138. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872.

Singh P, Rohtagi R, Soren S, Shukla M, Lindow SW: The prevalence of domestic violence in antenatal attendee’s in a Delhi hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008, 28: 272-275. 10.1080/01443610802042589.

Babu BV, Kar SK: Domestic violence against women in eastern India: a population-based study on prevalence and related issues. BMC Publ Health. 2009, 9: 129-10.1186/1471-2458-9-129.

Babu BV, Kar SK: Domestic violence in Eastern India: factors associated with victimization and perpetration. Public Health. 2010, 124: 136-148. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.01.014.

Dalal K, Lindqvist K: A national study of the prevalence and correlates of domestic violence among women in India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012, 24: 265-277. 10.1177/1010539510384499.

Chibber KS, Krupp K, Padian N, Madhivanan P: Examining the determinants of sexual violence among young, married women in Southern India. J Interpers Violence. 2012, 27: 2465-2483. 10.1177/0886260511433512.

Ackerson LK, Kawachi I, Barbeau EM, Subramanian SV: Effects of individual and proximate educational context on intimate partner violence: a population-based study of women in India. Am J Public Health. 2008, 98: 507-514. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113738.

Berg MJ, Kremelberg D, Dwivedi P, Verma S, Schensul JJ, Gupta K, Chandran D, Singh SK: The effects of husband’s alcohol consumption on married women in three low-income areas of Greater Mumbai. AIDS Behav. 2010, 14 (Suppl 1): S126-135.

Nayak MB, Patel V, Bond JC, Greenfield TK: Partner alcohol use, violence and women’s mental health: population-based survey in India. Br J Psychiatry. 2010, 196: 192-199. 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.068049.

Schensul SL, Mekki-Berrade A, Nastasi BK, Singh R, Burleson JA, Bojko M: Men’s extramarital sex, marital relationships and sexual risk in urban poor communities in India. J Urban Health. 2006, 83: 614-624. 10.1007/s11524-006-9076-z.

Jejeebhoy SJ, Cook RJ: State accountability for wife-beating: the Indian challenge. Lancet. 1997, 349: s10-12.

Raj A, Saggurti N, Lawrence D, Balaiah D, Silverman JG: Association between adolescent marriage and marital violence among young adult women in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010, 110: 35-39. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.022.

Speizer IS, Pearson E: Association between early marriage and intimate partner violence in India: a focus on youth from Bihar and Rajasthan. J Interpers Violence. 2011, 26: 1963-1981. 10.1177/0886260510372947.

Santhya KG, Ram U, Acharya R, Jejeebhoy SJ, Ram F, Singh A: Associations between early marriage and young women’s marital and reproductive health outcomes: evidence from India. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010, 36: 132-139. 10.1363/3613210.

Rapp D, Zoch B, Khan MM, Pollmann T, Kramer A: Association between gap in spousal education and domestic violence in India and Bangladesh. BMC Publ Health. 2012, 12: 467-10.1186/1471-2458-12-467.

Shah More N, Bapat U, Das S, Alcock G, Patil S, Porel M, Vaidya L, Fernandez A, Joshi W, Osrin D: Community mobilization in Mumbai slums to improve perinatal care and outcomes: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2012, 9: e1001257-10.1371/journal.pmed.1001257.

Officer of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Director of Census Operations Maharashtra: Provisional population totals: paper 1 of 2011. Census of India 2011. 2011, Maharashtra: New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India

More NS, Bapat U, Das S, Patil S, Porel M, Vaidya L, Koriya B, Barnett S, Costello A, Fernandez A, Osrin D: Cluster-randomised controlled trial of community mobilisation in Mumbai slums to improve care during pregnancy, delivery, postpartum and for the newborn. Trials. 2008, 9: 7-10.1186/1745-6215-9-7.

WHO: Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. WHO/FCH/GWH/01.1. 2001, Geneva: Department of Gender and Women’s Health, Family and Community Health, World Health Organization

WHO: WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. 2005, Geneva: World Health Organization

Filmer D, Pritchett L: Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data - or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001, 38: 115-132.

Vyas S, Kumaranayake L: Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006, 21: 459-468. 10.1093/heapol/czl029.

Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MTA: The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol. 1997, 26: 224-227. 10.1093/ije/26.1.224.

Shah More N, Bapat U, Das S, Barnett S, Costello A, Fernandez A, Osrin D: Inequalities in maternity care and newborn outcomes: one-year surveillance of births in vulnerable slum communities in Mumbai. Int J Equity Health. 2009, 8: 21-10.1186/1475-9276-8-21.

Dalal K: Does economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence?. J Inj Violence Res. 2011, 3: 35-44. 10.5249/jivr.v3i1.76.

Madhivanan P, Krupp K, Reingold A: Correlates of intimate partner physical violence among young reproductive Age women in mysore, India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011, doi:10.1177/1010539511426474 Epub ahead of print

Krishnan S, Rocca CH, Hubbard AE, Subbiah K, Edmeades J, Padian NS: Do changes in spousal employment status lead to domestic violence? Insights from a prospective study in Bangalore, India. Soc Sci Med. 2010, 70: 136-143. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.026.

Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, Nalugoda F, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kiwanuka N, Wagman J, Serwadda D, Wawer M, Gray R: Domestic violence in rural Uganda: evidence from a community-based study. Bull World Health Organ. 2003, 81: 53-60.

Taft AJ, Watson LF, Lee C: Violence against young Australian women and association with reproductive events: a cross-sectional analysis of a national population sample. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004, 28: 324-329. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2004.tb00438.x.

Silverman JG, Gupta J, Decker MR, Kapur N, Raj A: Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. BJOG. 2007, 114: 1246-1252. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01481.x.

Coker AL, Sanderson M, Dong B: Partner violence during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004, 18: 260-269. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00569.x.

Covington DL, Hage M, Hall T, Mathis M: Preterm delivery and the severity of violence during pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 2001, 46: 1031-1039.

Valladares E, Ellsberg M, Pena R, Hogberg U, Persson LA: Physical partner abuse during pregnancy: a risk factor for low birth weight in Nicaragua. Obstet Gynecol. 2002, 100: 700-705. 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02093-8.

Farid M, Saleem S, Karim MS, Hatcher J: Spousal abuse during pregnancy in Karachi, Pakistan. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008, 101: 141-145. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.11.015.

Salari Z, Nakhaee N: Identifying types of domestic violence and its associated risk factors in a pregnant population in Kerman hospitals, Iran Republic. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2008, 20: 49-55. 10.1177/1010539507308386.

Tiwari A, Chan KL, Fong D, Leung WC, Brownridge DA, Lam H, Wong B, Lam CM, Chau F, Chan A, et al: The impact of psychological abuse by an intimate partner on the mental health of pregnant women. BJOG. 2008, 115: 377-384. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01593.x.

Stephenson R, Koenig MA, Acharya R, Roy TK: Domestic violence, contraceptive use, and unwanted pregnancy in rural India. Stud Fam Plann. 2008, 39: 177-186. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.165.x.

Pallitto CC, Campbell JC, O’Campo P: Is intimate partner violence associated with unintended pregnancy? A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005, 6: 217-235. 10.1177/1524838005277441.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/817/prepub

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the women and their families who allowed us into their homes to interview them and shared information on a difficult subject. We thank all the community event identifiers, interviewers, and supervisors. We thank Latika Chordhekar, Dhanlaxmi Solanki, and Varsha Kokate for data handling. We thank Nayreen Daruwalla and the team from SNEHA’s program on prevention of violence against women and children for their support and advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study. SD supervised data collection, carried out the main analysis and wrote the first draft. UB supervised field activities and data collection. NSM was the project director. GA was technical adviser to the project. WJ and SP had overall responsibility for SNEHA programmes. DO helped with the analysis and edited drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Das, S., Bapat, U., Shah More, N. et al. Intimate partner violence against women during and after pregnancy: a cross-sectional study in Mumbai slums. BMC Public Health 13, 817 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-817

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-817