Abstract

Background

Lifestyle behavior modification is an essential component of self-management of type 2 diabetes. We evaluated the prevalence of engagement in lifestyle behaviors for management of the disease, as well as the impact of healthcare professional support on these behaviors.

Methods

Self-reported data were available from 2682 adult respondents, age 20 years or older, to the 2011 Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada’s diabetes component. Associations with never engaging in and not sustaining self-management behaviors (of dietary change, weight control, exercise, and smoking cessation) were evaluated using binomial regression models.

Results

The prevalence of reported dietary change, weight control/loss, increased exercise and smoking cessation (among those who smoked since being diagnosed) were 89.7%, 72.1%, 69.5%, and 30.6%, respectively. Those who reported not receiving health professional advice in the previous 12 months were more likely to report never engaging in dietary change (RR = 2.7, 95% CI 1.8 – 4.2), exercise (RR = 1.7, 95% CI 1.3 – 2.1), or weight control/loss (RR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.3 – 3.6), but not smoking cessation (RR = 1.0; 95% CI: 0.7 – 1.5). Also, living with diabetes for more than six years was associated with not sustaining dietary change, weight loss and smoking cessation.

Conclusion

Health professional advice for lifestyle behaviors for type 2 diabetes self-management may support individual actions. Patients living with the disease for more than 6 years may require additional support in sustaining recommended behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes is a major public health concern around the world. In Canada, over two million adults lived with the disease in 2009 [1, 2]. Considering that about 200,000 new cases are diagnosed yearly [1], the burden of diabetes is projected to increase [3]. It is also a major driver of the total health care cost and the sixth leading cause of death in Canada [4]. The vast majority (> 90%) of all cases are type 2 diabetes, diagnosed in older adults, and often associated with obesity [5].

Lifestyle behavior modification is a cornerstone for self-management of type 2 diabetes [6, 7]. Important components of self-management include maintaining a healthy diet, participating in regular physical activity, achieving and maintaining a healthy body weight, limiting alcohol intake, and not/quitting smoking. Because the complexity of diabetes management requires that health professionals work collaboratively with their patients [8], self-management support has become a critical element for effective diabetes self-management.

Although there are published studies on effective self-management among Canadians living with type 2 diabetes [9–11], data from a large nationally representative sample may provide further evidence to inform strategies that will support long-term maintenance of self-management behaviors. To date, few population-based studies have described the self-management practices of Canadian adults with type 2 diabetes. Among those that have [12, 13], the reported self-management behaviors are not consistent with guidelines for diabetes self-management [6]. A better understanding of these behavior patterns among persons living with the disease may provide vital information for public health planning.

In the present study, we set to 1) understand the extent to which Canadians living with type 2 diabetes employ different lifestyle behaviors for the management of the disease, by engaging in dietary change, exercise, weight control/loss, smoking cessation and limiting alcohol intake; 2) determine the proportion of persons with type 2 diabetes who receive healthcare professional advice and also engage in self-care behaviors; and 3) identify determinants of a) never engaging in these lifestyle behaviors, and b) not sustaining lifestyle behaviors for the management of type 2 diabetes.

Methods

The study is based on data from the 2011 Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada Diabetes Component (SLCDC-DM). Individuals age 20 years and older who reported having diabetes diagnosed by a health care professional as part of the 2010 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) were eligible for participation in the SLCDC-DM. Of the 3590 CCHS respondents contacted, 2933 individuals agreed to participate in the SLCDC-DM, resulting in a response rate of 81.7% [14]. Members of the Canadian Forces, First Nations individuals living on reserves, individuals residing in institutions, and residents of Canada’s three territories, Nunavut, Northwest Territories and Yukon Territory, and respondents who reported having diabetes only during pregnancy were excluded from the sampling frame [14]. Furthermore, respondents who reported having been diagnosed during pregnancy but did not state whether they had been diagnosed outside of pregnancy were excluded (n=7). The analysis was restricted to the population with self-reported type 2 diabetes; these were individuals who reported either having type 2 diabetes or did not report a type but reported being diagnosed after the age of 30 years.

The population represented in this survey was characterized by time since diagnosis (≤ 2 years, 3–5 years, 6+ years) and socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment, total household income, marital status, urban versus rural residence). Time since diagnosis was derived based on current age and responses to the question “How old were you when you were first diagnosed with diabetes?” With the exception of age, gender, and residence location, other information on socio-demographic characteristics was measured as part of the 2010 CCHS, which was linked to the 2011 SLCDC.

Participants were asked if, as a result of being diagnosed with diabetes, they ever: i) changed the type or amount of food, ii) changed the amount of exercise or participated in physical activities, and iii) stopped drinking or limited alcohol intake? Those who responded “yes” were further asked if they continued to maintain the change “all the time”, “most of the time”, “some of the time” or “none of the time” for dietary change, physical activity and alcohol intake. For our analysis, participants were categorized as not sustaining the self-management behavior change, if they reported “none of the time” or “some of the time”. Likewise, patients were also asked if, as a result of being diagnosed with diabetes, they ever: i) tried to control or lose weight, and ii) quit smoking. Patients who responded “yes” were further asked: are you continuing to maintain this change? Those who responded “no” were considered as not sustaining the self-management behavior change. Regular drinking of alcohol was defined as 14 standard drinks of alcohol/week for men or 9 standard drinks of alcohol/week for women [6].

Never engaging in lifestyle behaviors and not sustaining lifestyle behaviors were described according to whether the respondent reported having received self-management support (i.e. advice for the behavior from a health care professional) in the previous 12 months. For example, participants were asked “In the past 12 months, has a doctor or other health professional discussed changing the type or amount of food you eat to help you control your diabetes?” Similar questions were asked for physical activity/exercise, controlling/losing weight, quitting smoking, and limiting alcohol consumption.

The weighted prevalence of engaging in self-reported behaviors for type 2 diabetes management was estimated. Using cross tabulations, the weighted proportions of respondents engaging in self-management behaviors were estimated according to whether or not patients received health professional advice for lifestyle behaviors. Associations between descriptors and a) never engaging in lifestyle behaviors, and b) not sustaining lifestyle behaviors were examined using multivariate prevalence rate ratios (RRs), estimated using log-binomial regression models. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 4 (Cary, NC). Point estimates were weighted to reflect the Canadian adult population, with population estimates based on 2006 Census counts and counts of birth, death, immigration and emigration since that time [14, 15]. To account for stratification and clustering in the SLCDC design, 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using exact standard errors generated through bootstrap re-sampling methods [16].

Informed consent was obtained from all survey respondents. All personal information created, held or collected by Statistics Canada is protected by the Privacy Act and by the Statistics Act. Share partners, including the Public health Agency of Canada, have access to the data under the terms of the data sharing agreements. These data files only contain information on respondents who agreed to share their data with Statistics Canada’s partners.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Of the 2933 respondents to the survey, 2682 (91.4%) who reported type 2 diabetes were included in these analyses, excluding those with type 1 diabetes mellitus. The total sample was based on either their self-reported type 2 diabetes (n=2351) or age at diagnosis ≥ 30 years (n=331). The socio-demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The respondent sample was predominantly male (58.1%), living in urban regions (82.4%), and almost half were diagnosed over ten years ago (44.9%).

Prevalence of lifestyle behaviors

Since being diagnosed with diabetes, 89.7% of the respondents reported changing the type or amount of food they ate; 69.5% increased their amount of exercise or participation in physical activity; 55.6% were trying to control or lose weight. Among those who drank more than 9 alcoholic drinks/week for women and 14 drinks/week for men at diagnosis, 42.8% reported that they reduced their alcohol intake.

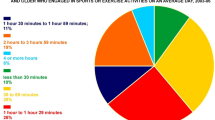

Overall, less than half reported engaging in each of the lifestyle behaviors all of the time: 37.0% for diet; 18.0% for physical activity or exercise; 39.8% for weight control; 30.6% for smoking cessation; and 17.7% for limiting alcohol. Among those who reported smoking at diagnosis (23.8%), half (50.5%) never quit and 18.9% tried to quit, but had not sustained the change (Table 2).

Participants who reported having discussed behavior change with a health professional were more likely to report behavior modification compared to those who did not report receiving advice for diet (95.7% vs. 85.0% p < 0.0001), physical activity (79.6% vs. 60.7%, p < 0.0001), weight loss (94.5% vs. 88.9%, p < 0.002), and limiting alcohol consumption (among those who reported drinking alcohol, 74.6% vs. 40.2%, p = 0.04) (Table 3).

Associations with never engaging/notsustaining lifestyle behaviors

In multivariate analysis, an increased prevalence of never changing their diet was associated with being male (RR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.3 – 2.8), age ≥ 65 years (RR = 2.6, 95% CI 1.6 – 4.2), or having less than secondary education (RR = 1.7, 95% CI 1.2 – 2.4) (Table 4). Compared to those with total household income ≥ 80,000 CAD, individuals with lower income levels were more likely to report never having changed their diet (RRs ranging from 3.8 to 4.5) or never engaged in exercise (RRs ranging from 1.6 to 2.1). Also, not receiving advice for the specific self-management behavior from health professionals in the previous 12 months was associated with never engaging in lifestyle behavior for: diet (RR = 2.7, 95% CI 1.8 – 4.2), exercise (RR = 1.7, 95% CI 1.3 – 2.1), or controlling/losing weight (RR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.3 – 3.6).

Among those who reported ever engaging in diabetes self-management lifestyle behavior change, living with diabetes for 6 or more years was associated with not sustaining diet change (RR = 2.0, 95% CI 1.2 – 3.4), weight loss (RR = 1.8, 95% CI 1.2 – 2.6), and smoking cessation (RR = 3.8, 95% CI 1.0 – 13.9). Similar findings were observed for persons who had lived with diabetes for over 10 years (Table 5). No differences were noted in our findings after adjusting for patients’ use of support services or programs.

Discussion

In this study describing the self-reported self-management behaviors in a nationally representative sample of adult Canadians living with type 2 diabetes, we observed that lifestyle behavior change (in particular dietary change, exercise and weight control) appeared to be prevalent following a diagnosis, especially among patients who receive self-management advice from a health professional. However, smoking cessation may represent a challenge; only 31% of those who reported having smoked after diagnosis reported having successfully quit. Among persons who ever engaged in lifestyle behaviors for self-management, persons living with diabetes for over 6 years were more likely to not sustain the behaviors.

The finding that persons who do not receive health professional advice for behavior change are less likely to engage in diabetes self-management behaviors is consistent with previous findings [17, 18]. Individuals with type 2 diabetes who receive self-management support from physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians or other health professionals on the management of their diet [18], exercise and weight management [19] or combinations thereof [20] are generally more likely to make such changes. In a randomized control trial of patients with type 2 diabetes [19], a brief intervention to increase dialogue between patients and health care providers about lifestyle behavior modification for diabetes self-management significantly improved the level of recommended physical activity and weight loss. Our findings highlight the importance of health care provider communication, either through the provision of information or participatory decision-making, in patients’ behaviors for diabetes self-management. Better healthcare provider communication may lead to better diabetes self-management and, in turn, improve health outcomes, including higher levels of patient satisfaction [21–23]. Nonetheless, it is important to also note that substantial numbers of individuals who reported not receiving advice from health professional for change in diet, exercise or weight still engaged in self-management behaviors, and may have accessed support services or programs independent of health professional advice. Whether these individuals were already living healthy lifestyles and are less likely to receive health professional advice could not be addressed with these data and therefore remains to be studied.

The prevalence of smoking among adults with type 2 diabetes in this study is comparable to previous reports in adult Canadians living with diabetes [1] and it is interesting that no difference was observed in the proportion of respondents who ever engaged in smoking cessation in our multivariate analyses. The null effect of healthcare provider dialogue on smoking cessation observed in this study highlights the need for a more rigorous smoking cessation program for diabetes care, apart from standard or usual care self-management education in persons with diabetes [24, 25]. The American Diabetes Association, for instance, recommends healthcare providers to utilize more intensive interventions for smoking cessation as a priority of care for diabetic smokers [7]. Because smoking exacerbates the risk of developing both macrovascular and microvascular complications in patients with diabetes [26], the Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines asserts that “the first priority” in the prevention of diabetes complications should be the reduction in the risk for cardiovascular disease through a multifaceted, multi-factorial, approach, including smoking cessation [6].

Persons with lower household income were more likely to report never changing their diet or not engaging in exercise for self-management of type 2 diabetes. Socio-economic status (SES) is an important determinant of diabetes self-management behaviors, particularly diet and exercise. Socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with a wide range of risk behaviors, which in turn have a negative consequence on health [27]. It is possible that this relationship is mediated by poor adherence to diabetes self-management recommendations, which is related to low accessibility to healthy foods and health promotion facilities. Elimination of disparities in health, through policies and interventions to improve access and quality of care in patients with type 2 diabetes should be prioritized.

We observed that persons living with diagnosed type 2 diabetes for more than 6 years are more likely to not sustain lifestyle behavior changes for diabetes self-management. In another Canadian study [28], self-management education was shown to have a significant impact in healthy eating among diabetes patients, and was sustained at 2 years. The study did not, however, capture the self-management behavior sustenance for more than 2 years. Our results indicate that persons living with type 2 diabetes for more than 6 years may need specific attention to maintain behavior change. Further studies are necessary to understand barriers to sustained self-management behavior change among patients living with the disease for longer durations.

The Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada is a population-based cross-sectional survey designed to provide information on chronic disease management among Canadians living with chronic diseases. Several limitations are noted. First, the survey was insufficiently powered to assess the effect of ethnicity on engagement in lifestyle behaviors. Because multiple ethnic populations known to be culturally and epidemiologically heterogeneous [29] were combined as a single category, differences in diabetes self-management behavior among these populations may have been masked. Second, it is acknowledged that self-reported adherence to recommended lifestyle behaviors can be overestimated in self-reported surveys due to social desirability. Our findings nevertheless provide an important profile of the relative prevalence of self-reported lifestyle behaviors for managing type 2 diabetes. Likewise, participants may not accurately remember the healthcare services they received from their healthcare providers; research has shown that a patient’s ability to retain information from health professionals is often limited, with 40-80% of information forgotten immediately [30, 31].

Third, the survey explores a limited range of determinants of lifestyle behaviors, and did not capture specific measures of lifestyle behavior change, e.g. patients’ self-reported engagement in physical activity was captured, without reference to the exercise intensity. The use of direct measures of physical activity (such as accelerometry), which would provide a more accurate estimate of physical activity levels including the intensity, was not feasible for this large national survey. On another note, never engaging and not sustaining lifestyle behaviors were described according to whether the respondent reported having received advice for the behavior from a health care professional. It is certainly possible that some patients changed their lifestyle behaviors on their own, with the use of self help books, internet, or other sources without having received specific advice from a health care professional [32].

This study may have some implications for action. First, although there is a high prevalence of diabetes self-management behavior modification among people living with type 2 diabetes in Canada, the findings suggest a need for more action. Receipt of advice from health care professionals is strongly associated with self-reported engagement in self-management behaviors. Of note, however, is the limited effect of dialogue on smoking cessation among patients with type 2 diabetes that smoke. This, perhaps, indicates a need for more aggressive smoking cessation interventions. Finally, the study notes that SES-dependent disparities in healthy lifestyle behaviors are observed among Canadians living with type 2 diabetes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that among adult Canadians living with type 2 diabetes, self-management behavior change is common, particularly among newly diagnosed individuals and those receiving lifestyle behavior change advice from health professionals. More action is needed for improved diabetes self-management among those living with the disease for longer durations, those with lower socioeconomic status, and those patients who continue to smoke. Provision of information and advice for lifestyle behavior at the primary care level, and targeted to these higher risk groups, may be an effective health promotion strategy.

References

Public Health Agency of Canada. Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective. 2011, Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/publications/diabetes-diabete/facts-figures-faits-chiffres-2011/index-eng.php. Accessed on May 22, 2012

Public Health Agency of Canada. Report from the National Diabetes Surveillance System: diabetes in Canada. 2008, Ottawa, Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada, http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2009/ndssdic-snsddac-09/index-eng.php. Accessed on May 22, 2012

Ohinmaa A, Jacobs P, Simpson S, Johnson J: The projection of prevalence and cost of diabetes in Canada: 2000 to 2016. Can J Diabetes. 2004, 28 (2): 00-00.

Statistics Canada: Leading causes of death in Canada, 2000 to 2004 (Catalogue 84-215-X). 2008, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/84-215-x/2012001/tbl/t001-eng.htm .Accessed on May 22, 2012

PHAC: Public Health Agency of Canada. Fast facts about Diabetes: Data compiled from the 2011 Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada. 2011, Ottawa, http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/publications/diabetes-diabete/ff-rr-2011-eng.php,

Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee: Canadian diabetes association 2008 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in canada. Can J Diabetes. 2008, 32: S1-S201.

American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes Care. 2011, 34 (Suppl 1): S11-61.

Siminerio L: Overcoming Barriers to Better Health Outcomes in Patients with Diabetes – Improving and Balancing Patient Education and Pharmacotherapy Initiation, European Endocrinology - Diabetes Management. US Endocrinology. 2008, 4 (2): 44-46.

Graham L, Sketris I, Burge F, Edwards L: The effect of a primary care intervention on management of patients with diabetes and hypertension: a pre-post intervention chart audit. Healthc Q. 2006, 9 (2): 62-71.

Johnson ST, Bell GJ, McCargar LJ, Welsh RS, Bell RC: Improved cardiovascular health following a progressive walking and dietary intervention for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009, 11 (9): 836-843. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01050.x.

Millar A, Cauch-Dudek K, Shah BR: The impact of diabetes education on blood glucose self-monitoring among older adults. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010, 16 (4): 790-793. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01195.x.

Plotnikoff RC, Karunamuni ND, Johnson JA, Kotovych M, Svenson LW: Health-related behaviours in adults with diabetes: associations with health care utilization and costs. Can J Public Health. 2008, 99 (3): 227-231.

Plotnikoff RC, Taylor LM, Wilson PM, Courneya KS, Sigal RJ, Birkett N, Raine K, Svenson LW: Factors associated with physical activity in Canadian adults with diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006, 38 (8): 1526-1534. 10.1249/01.mss.0000228937.86539.95.

Statistics Canada: Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada - 2011 User Guide. 2011, Statistics Canada, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/cgi-bin/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getDocumentationLink&Item_Id=119561&qItem_Id=84771&TItem_Id=84769&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2 . Accessed on May 22, 2012

Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) Annual component User guide:. 2010, [http://www.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/document/3226_D7_T9_V8-eng.pdf], and 2009–2010 Microdata files

Rao JNK: Symposium 2010: Social Statistics: The Interplay Among Censuses, Surveys and Administrative Data. Statistics Canada International Symposium Series: Proceedings. Edited by: Canada S. 2010, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?lang=eng&catno=11-522-X200600110416 Accessed on May 22, 2012

Otero-Sabogal R, Arretz D, Siebold S, Hallen E, Lee R, Ketchel A, Li J, Newman J: Physician-community health worker partnering to support diabetes self-management in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2010, 18 (6): 363-372.

Siddiqui A, Gul A, Ahmedani MY, Masood Q, Miyan ZM: Compliance to dietary counseling provided to patients with type 2 diabetes at a tertiary care hospital. J Diabetology. 2010, 1: 5-

Christian JG, Bessesen DH, Byers TE, Christian KK, Goldstein MG, Bock BC: Clinic-based support to help overweight patients with type 2 diabetes increase physical activity and lose weight. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168 (2): 141-146. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.13.

Andrews RC, Cooper AR, Montgomery AA, Norcross AJ, Peters TJ, Sharp DJ, Jackson N, Fitzsimons K, Bright J, Coulman K: Diet or diet plus physical activity versus usual care in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: the Early ACTID randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011, 378 (9786): 129-139. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60442-X.

Heisler M, Cole I, Weir D, Kerr EA, Hayward RA: Does physician communication influence older patients’ diabetes self-management and glycemic control? Results from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007, 62 (12): 1435-1442. 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1435.

Heisler M, Tierney E, Ackermann RT, Tseng C, Narayan KM, Crosson J, Waitzfelder B, Safford MM, Duru K, Herman WH: Physicians’ participatory decision-making and quality of diabetes care processes and outcomes: results from the triad study. Chronic Illn. 2009, 5 (3): 165-176. 10.1177/1742395309339258.

Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, Smith DM, Kerr EA: The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. J Gen Intern Med. 2002, 17 (4): 243-252. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x.

Hokanson JM, Anderson RL, Hennrikus DJ, Lando HA, Kendall DM: Integrated tobacco cessation counseling in a diabetes self-management training program: a randomized trial of diabetes and reduction of tobacco. Diabetes Educ. 2006, 32 (4): 562-570. 10.1177/0145721706289914.

Canga N, De Irala J, Vara E, Duaso MJ, Ferrer A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA: Intervention study for smoking cessation in diabetic patients: a randomized controlled trial in both clinical and primary care settings. Diabetes Care. 2000, 23 (10): 1455-1460. 10.2337/diacare.23.10.1455.

Haire-Joshu D, Glasgow RE, Tibbs TL: Smoking and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27 (Suppl 1): S74-75.

Dinca-Panaitescu S, Dinca-Panaitescu M, Bryant T, Daiski I, Pilkington B, Raphael D: Diabetes prevalence and income: results of the canadian community health survey. Health Policy. 2011, 99 (2): 116-123. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.07.018.

Vallis TM, Higgins-Bowser I, Edwards L, Murray A, Scott L: The role of diabetes education in maintaining lifestyle changes. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2005, 29 (3): 193-202.

Nwasuruba C, Osuagwu C, Bae S, Singh KP, Egede LE: Racial differences in diabetes self-management and quality of care in Texas. J Diabetes Complications. 2009, 23 (2): 112-118. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.11.005.

Kessels RP: Patients’ memory for medical information. J R Soc Med. 2003, 96 (5): 219-222. 10.1258/jrsm.96.5.219.

McGuire LC: Remembering what the doctor said: organization and adults’ memory for medical information. Exp Aging Res. 1996, 22 (4): 403-428. 10.1080/03610739608254020.

Plotnikoff RC, Johnson ST, Karunamuni N, Boule NG: Physical activity related information sources predict physical activity behaviors in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Health Commun. 2010, 15 (8): 846-858. 10.1080/10810730.2010.522224.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/451/prepub

Acknowledgements

CBA is a research associate supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Team Grant to the Alliance for Canadian Health Outcomes Research in Diabetes (reference #: OTG- 88588), sponsored by the CIHR Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes. JAJ is a Senior Scholar with Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions and holds a Canada Research Chair in Diabetes Health Outcomes. The funding body had no role in the study design or conduct; in data collection, management, analysis or interpretation; preparation or review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

CBA: Conception and design, interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript and revision of manuscript. MEG: Data acquisition, conception and design, data analysis, critical revision of manuscript. STJ, PD, MFL and LAL: Conception and design, interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript. CP: Data acquisition, conception and design and critical revision of manuscript. JAJ: Conception and design, interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Agborsangaya, C.B., Gee, M.E., Johnson, S.T. et al. Determinants of lifestyle behavior in type 2 diabetes: results of the 2011 cross-sectional survey on living with chronic diseases in Canada. BMC Public Health 13, 451 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-451

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-451