Abstract

Background

It is well known that the prevalence of asthma has been reported to increase in many places around the world during the last decades. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify and review studies of asthma prevalence among children in China and address time trends and regional variation in asthma.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed using PubMed and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases. Selected articles had to describe an original study that showed the prevalence of asthma among children aged 0−14 years.

Results

A total of 74 articles met the inclusion criteria. The lifetime prevalence of asthma varied between 1.1% in Lhasa (Tibet) and 11.0% in Hong Kong in studies following the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) protocol. The prevalence was 3% or lower in most articles following Chinese diagnostic criteria. One article reported the results from two national surveys and showed that the current average prevalence of asthma for the total study population had increased from 1990 to 2000 (0.9% to 1.5%). The lowest current prevalence was found in Lhasa (0.1% in 1990, 0.5% in 2000).

Conclusions

The prevalence of childhood asthma was generally low, both in studies following the ISAAC and Chinese diagnostic criteria. Assessment of time trends and regional variations in asthma prevalence was difficult due to insufficient data, variation in diagnostic criteria, difference in data collection methods, and uncertainty in prevalence measures. However, the findings from one large study of children from 27 different cities support an increase in current prevalence of childhood asthma from 1990 to 2000. The lowest current prevalence of childhood asthma was found in Tibet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is well known that the prevalence of asthma has been reported to increase in many places around the world during the last decades [1]. The causes of asthma and why asthma seems to have increased is still not well understood. The increase in asthma prevalence has been suggested in some way to be related to western lifestyle factors, as most often increased prevalence rates are reported from westernized countries [2, 3]. Further support for the western lifestyle hypothesis would be to show that the development of asthma prevalence follows the same pattern in societies going through a transition from a more traditional to a more modern lifestyle. Such a transition is currently taking place in China at a much higher speed and during a shorter period than in many other countries [4]. It is likely that the speed of this process and how far the process has already gone varies in different parts of China. Geographically, Tibet is one of the highest regions in the world. Local residents consist mainly of native Tibetans who have lived there for a long time. Furthermore, in Tibet there are areas in which traditional lifestyle still dominates while in Lhasa, the main city, the way of living has already started to develop in a more modern direction due to increasing communication with the rest of the world. Hence, assessing regional population based asthma prevalence and time trends in occurrence of asthma in China and especially in Tibet will provide useful background information for future public health planning, and it may also add to the understanding of how living conditions and ethnic background are related to the occurrence of asthma.

The aim of the current review was therefore to identify and assess studies that have reported asthma prevalence among children in China and search for time trends and regional variation with a special focus on studies among Tibetan children.

Methods

Identification of studies

A systematic literature search was performed to identify all relevant publications on asthma prevalence among children aged 0−14 years in China and Tibet, published between 1991 and 2011.

An electronic search was undertaken of the following databases: “PubMed” and the “China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)”.

For studies based on the protocol of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) we used the following search terms in the PubMed database: (KY= child or KY= childhood) and KY= asthma and (KY= China or KY= Chinese) and KY= ISAAC and KY= prevalence. In the CNKI database in articles following ISAAC protocol we used Chinese search terms, here translated into English: (KY= child or KY= adolescent) and (KY= asthma or KY= bronchial asthma) and FT= ISAAC.

For studies following the Chinese diagnostic criteria we used the following Chinese search terms in the CNKI database, here translated into English: (KY= child or KY= adolescent or TI= infant or TI= child TI= adolescent) and (KY= asthma or KY= bronchial asthma or TI= asthma or TI= bronchial asthma) and (KY= prevalence or KY= epidemiology or TI= survey).

The reference lists of relevant articles were reviewed for additional articles. Some authors of included studies were contacted to identify additional publications. The search results were screened by two authors independently. All included articles were read in full-text.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the review articles had to meet the following criteria:

-

1)

For studies according to the ISAAC study protocol

-

a)

To report prevalence of asthma among children aged 0−14 years.

-

b)

To follow the ISAAC protocol.

-

a)

-

2)

For studies based on the Chinese diagnostic criteria

-

a)

To report prevalence of asthma among children aged 0−14 years.

-

b)

To follow one of five sets of Chinese diagnostic criteria for asthma that were established by the First Children Respiratory Diseases Conference (FCRDC) in 1987 [5], the National Cooperation Group on Childhood Asthma (NCGCA) of 1993 or 1998 [6, 7], and the Branch for Respiratory Diseases of Chinese Medical Association (BRDCMA) of 1997 or 2003 [8, 9].

-

a)

Articles written in English and Chinese were included. If results based on the same data were presented in more than one publication, results from only one publication were included. Studies lacking clear presentation of prevalence or diagnostic criteria were not included.

Data extraction criteria

A standardized reporting form was used to extract data from each publication. The form included: first author's name, year of publication, place in which the study was conducted, year of data collection, sample size, age range of study subjects, prevalence estimates and response rate.

Outcome measures

Asthma prevalence according to the ISAAC study protocol

ISAAC was founded to maximize the value of epidemiological research into asthma and allergic disease by establishing a standardized methodology and facilitating international collaboration [10]. For studies following the ISAAC protocol, the lifetime prevalence of asthma was based on the answer provided by 12−14 year-old children to the written question “Have you ever had asthma?” and the answer provided by their parents or guardians to the written question “Has your child ever had asthma?” for 6−7 and 9−11 year-old children [11]. ISAAC has also developed a video questionnaire for assessing asthma symptoms prevalence. The video questionnaire was completed by participants while watching five sequences of persons with different asthma symptoms [12]. Results from assessing the prevalence of asthma symptoms by the video questionnaire are presented when available. ‘Current asthma’ was defined as having asthma with symptoms in the last 12 months [11].

Asthma prevalence based on the Chinese diagnostic criteria

For the studies that followed Chinese diagnostic criteria, asthma had to be diagnosed by a physician according to the asthma diagnostic criteria established by FCRDC, NCGCA and BRDCMA between 1987 and 2003. These five sets of diagnostic criteria are similar and prescribe that diagnosis of asthma for children less than three years old had to include the experience of three or more outbreaks of wheezing, and confirmed whistling sounds from the lungs heard by the doctor during examination or documented from medical records. In addition, the diagnosis of asthma for children aged three or older had to meet the criteria mentioned above, and the children had to have experienced a distinct curative effect after treatment with bronchodilators. ‘Current asthma’ was defined as having asthma with symptoms during the last two years [13].

Results

Study characteristics

We identified 87 potentially relevant articles mentioning ISAAC (Figure 1). From these articles, we excluded 60 articles after reviewing titles and abstracts and excluded 15 more after a full review of the articles. Thus, in this review we included prevalence estimates of asthma from 12 articles (10 in English and 2 in Chinese) [14–25].

We identified 394 potentially relevant articles in Chinese (Figure 2). Frome these articles, 282 were excluded after reviewing titles and abstracts. Consequently a total of 112 articles were reviewed in full-text from which 50 articles were excluded, leaving 62 articles in the final review list [13, 26–86].

Participant characteristics

In seven articles following the ISAAC protocol, children were 12−14 years of age and the questionnaire was completed by the children themselves. In the remaining five articles, the children were aged 6−7 and 9−11 years and the questionnaire was completed by their parents or guardians. In six articles, results from the video questionnaire were also reported. The response rate was more than 90% in all studies.

In 62 articles which followed the Chinese diagnostic criteria, the response rate was reported to be more than 95% in 30 articles while the other 32 articles did not report a precise response rate. Furthermore, half of the articles did not report age specific prevalence of asthma.

Asthma prevalence

In the ISAAC articles (Table 1) the lifetime prevalence of asthma varied between 1.1% in Lhasa (Tibet) and 11.0% in Hong Kong. The lifetime prevalence was higher among children in Hong Kong compared with children from other cities like Beijing and Guangzhou both among children aged 9−11 and 12−14 years. In contrast, the lifetime prevalence of asthma among children aged 6−7 years was higher in Beijing compared with Hong Kong and Urumqi. One article from Beijing reported that the lifetime prevalence was higher in an urban compared to a rural area (6.3% vs. 1.1%) while lifetime prevalence was lower in an urban than a rural area based on reports from two studies in Tibet (1.1% vs. 2.5%). One article reported current prevalence of asthma among 10-year-old children in Hong Kong, Beijing and Guangzhou (3.3%, 2.3% and 2.1%, respectively) [25].

Lifetime prevalences of all five asthma symptoms based on ISAAC video questionnaire, were highest in Hong Kong (Table 2). Tibet had the lowest reported prevalences of asthma symptoms and the prevalences were higher in the rural area of Tingri and Sakya than in an urban area of Lhasa. In Guangzhou the prevalences of asthma symptoms were higher in 2001 than in 1994−1995 for four of the symptoms.

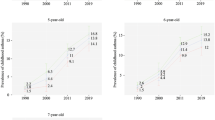

For the asthma prevalence based on the Chinese diagnostic criteria, the current prevalence of childhood asthma from 42 different places in China is shown in Figure 3[13, 26, 28, 29, 31]. Most of the results are extracted from two national surveys of a total of 399,193 children aged 0−14 from 1990 and 287,329 in 2000 all living in urban areas [13, 26]. The average current prevalence of asthma increased from 0.9% to 1.5% based on estimates from a national survey of children in 27 cities in 1990 and 2000 and statistically significantly increased in 22 out of 27 cities with estimates from both time points [13]. Age stratified analysis showed that the prevalence has increased in most age groups [13]. In addition, we identified three more articles from urban areas carried out in the same period [28, 29, 31]. The highest current prevalence was found in Chongqing (2.6%) and the lowest in Lhasa (0.1%) in 1990. In 2000, the highest current prevalence was found in Hefei (3.9%) and the lowest in Xining (0.1%). With a few exceptions, cities located in eastern China had higher current prevalences than cities in other parts of the country. There was no clear trend in current prevalence of childhood asthma according to the study populations' living altitude besides that the lowest current prevalence was reported from Lhasa (3,700 meters above sea level) [34] and Xining (2,200 meters above sea level) [35].

In 1990, only three articles reported lifetime prevalence (0.1−0.4%). In 2000, the highest lifetime prevalence was found in Chongqing (4.6%) and the lowest again in Xining (0.3%). Most of these articles reported lifetime prevalences of asthma below 3%. Results from these articles are presented in the Additional file 1: Table S1.

In addition, for the asthma prevalence based on the Chinese diagnostic criteria, we reviewed three more studies conducted in 1991, 2003−2004 and 2007−2008. In Beijing the current prevalence was 0.9%, in Huainan the current prevalence was 3.0% and the lifetime prevalence 4.1%, and in Nanhai the lifetime prevalence was 2% [36–38].

For asthma prevalence based on the Chinese diagnostic criteria, we found 10 articles with uncertainty about whether the reported childhood asthma prevalences expressed current or lifetime prevalences [39–48]. Furthermore, our review included 40 more articles which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. These articles were found difficult to assess due to differences and uncertainties in the presented outcome measures [49–88]. Some results from these 50 articles are presented in the Additional file 2: Table S2.

Discussion

Lifetime prevalence of childhood asthma based on articles using the ISAAC written questionnaire varied from 1.1 to 11.0% with the lowest prevalence found among Tibetan children. The pattern with lowest prevalence in Tibet was also seen in articles on asthma related symptoms based on the ISAAC video questionnaire and in articles based on the Chinese diagnostic criteria. There were some variation and uncertainties about how asthma prevalences were assessed in some of the articles following the Chinese diagnostic criteria. Even so, most of these articles reported asthma prevalences below 3%. One article presented asthma prevalences for children living in 43 different cities in 2000. Current prevalence varied between 0.1−3.3% and lifetime prevalence varied between 0.3−4.6%. The highest prevalence was found in Chongqing and the lowest in Xining. Lhasa had the second lowest prevalence [26]. Another article presented the current asthma prevalence for large populations of children living in 27 different cities. The average current prevalence estimates were 0.9% in 1990 and 1.5% in 2000 [13].

In this review, the assessment of population-based estimates of asthma prevalence and assessment of regional variation and changes over time turn out to be difficult due to, for instance, differences in diagnostic criteria, data collection methods, sampling of populations and how prevalences are measured. Studies based on the ISAAC protocol relied on self-reports or parental reports of asthma, while this was not sufficient information for the articles following the Chinese diagnostic criteria. In these latter articles physicians had to evaluate the collected information for each potential asthma case and make sure that a set of necessary criteria were fulfilled. The differences described above point towards the need to have reasonably similar disease definitions and data collection methods in order to be able to compare prevalences between studies. Another potential source of uncertainty for the comparisons was the fact that in some articles it was unclear whether lifetime prevalence or current prevalence was presented. The diagnosis of asthma in children younger than three years old was made by clinical criteria, but one could question the reliability of diagnosis of asthma in children at that age. Information on age distribution was often insufficiently presented in studies following Chinese diagnostic criteria, another source of uncertainty when comparing the studies. Taking the above mentioned sources of uncertainty into account we tried to compare articles that seemed to have reasonably comparable outcome definition and data collection methods. For some of the articles this turned out to be more difficult than for others and they were therefore given less attention and results from several articles are only presented in a supplement for completeness.

The five versions of diagnostic criteria for asthma used in articles following the Chinese diagnosis criteria were all quite similar, and we did not consider that these minor differences would substantially distort the comparisons of asthma prevalences between these studies. The size of the population samples were large, especially for the articles based on Chinese diagnostic criteria reducing the problem of random errors.

Secular trend in disease occurrence is difficult to document, especially for diseases like asthma, in which self-report of symptoms has to be a major part of disease ascertainment [89]. It is a common belief that the prevalence of asthma has been increasing in many societies around the world, even if some authors have raised questions about how to adjust for increasing awareness in the populations and among health workers [90–92]. One of the articles in this review was convincingly able to show that there was an average increase in registered cases of current asthma between 1990 and 2000. The study population included a huge sample of children and the data collection methods were comparable for the subsamples of the population. The increase in current asthma prevalence is further supported by the finding of increased occurrence in the majority of the cities and in the age stratified comparisons in the study. The findings support an increased occurrence of asthma within the study period even if one cannot exclude effects of potential changes in awareness and minor changes in diagnostic criteria from 1990 and 2000.

Results from the two national surveys presenting asthma prevalences showed that the prevalences were higher in cities in the eastern part compare to cities in other parts of China. However, the prevalences were low all over China with small absolute differences. Furthermore, the prevalences had more often been assessed in urban than in rural areas, making it difficult to compare the difference in prevalence between urban and rural areas. This was also the case for the ISAAC studies as most of the surveys had been conducted in larger and more modern cities, like Hong Kong and Beijing. Furthermore, the prevalence of asthma in ISAAC studies from China were lower than in ISAAC studies carried out in many other places in the world and especially in developed countries like Austria (32%) [93], United States of America (24.4%) [94], United Kingdom (14.9%) [95] and Singapore (27.4%) [96]. These findings are consistent with the idea that the degree of modernization or westernization is relate to higher prevalence of asthma.

The effect of living altitude was difficult to assess since most studies were conducted in populations living at rather low altitude. One exception was studies from Tibet, which presented some of the lowest prevalence figures regardless of the type of asthma definition used. It is tempting to speculate that factors like the high living altitude, the extreme climate or other living conditions as well as the high child mortality could have contributed to this [97, 98]. However, these are speculations, as so far as few studies have been carried out in Tibet to corroborate them. The finding of higher asthma prevalence in rural Tingri and Sakya (4,300 meters above sea level) than in urban Lhasa (3,700 meters above sea level) additionally complicates such speculations. It could only be a by chance finding and both prevalences should be considered as extremely low.

Conclusions

Assessment of childhood asthma prevalences in China and Tibet, and assessment of regional variation and change over time are difficult due to several uncertainties in the reviewed articles. Asthma prevalence in China was generally low and there were observations supporting the view that asthma prevalence had increased between 1990−2000. The available data gave limited possibility to address regional variation. However, the findings showed that the asthma prevalence in Tibet was in the lowest end of what has been reported elsewhere in China and clearly lower than in most places in the world. Tibet is characterized by extremely high living altitude, extreme climate and high child mortality. The influence of modern lifestyle has only been of minor importance until recently, especially in rural areas. The linking of these conditions to the low asthma prevalence in Tibet is not corroborated yet. It will be interesting to follow future trends in asthma prevalence. Assessing time trends in asthma prevalence is difficult due to the need to rely to some extent on self and parents reporting of symptoms, which may be influenced by increased awareness of asthma in the population as well as among data collectors. Furthermore one needs to ensure that data are optimally collected and comparable with earlier data.

References

Manning PJ, Goodman P, O'Sullivan A, Clancy L: Rising prevalence of asthma but declining wheeze in teenagers (1995-2003): ISAAC protocol. Ir Med J. 2007, 100: 614-615.

Beasley R, Crane J, Lai CK, Pearce N: Prevalence and etiology of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000, 105: S466-472. 10.1016/S0091-6749(00)90044-7.

Britton J: Parasites, allergy, and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 168: 266-267. 10.1164/rccm.2305011.

Yang G, Kong L, Zhao W, Wan X, Zhai Y, Chen LC, et al: Emergence of chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Lancet. 2008, 372: 1697-1705. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61366-5.

Hua YH, Chen YZ: The criterion of diagnostic and type on bronchial asthma. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Pediatr. 1988, 26: 41-42.

National Cooperation Group on Childhood Asthma (NCGCA): The conventions for the prevention and treatment of childhood asthma (Tentative regulations). (Article in Chinese). Chin J Pediatr. 1998, 36: 747-751.

National Cooperation Group on Childhood Asthma(NCGCA): Dignostic criteria and regular treatment of childhood asthma. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Chil Health Care. 1993, 1: 249-250.

Branch of Chinese Medical Association for Respiratory Diseases (BCMARD): Bronchial asthma therapeutic guidelines (Definition, diagnosis, treatment, healing effect criteria, education and management of bronchial asthma ). (Article in Chinese). Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis. 1997, 20: 261-267.

Branch of Chinese Medical Association for Respiratory Diseases (BCMARD): Bronchial asthma therapeutic guidelines (Definition, iagnosis, treatment, education and management of bronchial asthma ). (Article in Chinese). Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis. 2003, 26: 132-138.

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): ISAAC Home Page. 2011, http://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/. Last revised 9 Aug 2011

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Manual. 1993, http://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/phases/phaseone/phaseonemanual.pdf. Last revised 9 Aug 2011

International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): Instructions for use of the Video qustionnaire. 2011, http://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/phases/phaseone/videoinstructions.html. Last revised 9 Aug 2011

*Chen YZ: Comparative analysis of the state of asthma prevalence in children from two nation wide surveys in 1990 and 2000 year. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis. 2004, 27: 112-116.

Leung R, Wong G, Lau J, Ho A, Chan JK, Choy D, et al: Prevalence of asthma and allergy in Hong Kong schoolchildren: an ISAAC study. Eur Respir J. 1997, 10: 354-360. 10.1183/09031936.97.10020354.

Wong GW, Leung TF, Ko FW, Lee KK, Lam P, Hui DS, et al: Declining asthma prevalence in Hong Kong Chinese schoolchildren. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004, 34: 1550-1555. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02064.x.

Lau YL, Karlberg J: Prevalence and risk factors of childhood asthma, rhinitis and eczema in Hong Kong. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998, 34: 47-52. 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1998.00217.x.

Lee SL, Wong W, Lau YL: Increasing prevalence of allergic rhinitis but not asthma among children in Hong Kong from 1995 to 2001 (Phase 3 International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood). Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004, 15: 72-78. 10.1046/j.0905-6157.2003.00109.x.

Wong GW, Hui DS, Chan HH, Fok TF, Leung R, Zhong NS, et al: Prevalence of respiratory and atopic disorders in Chinese schoolchildren. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001, 31: 1225-1231. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01140.x.

Chen YZ, Zhao TB, Ding Y, Wang HJ, Wang HY, Zhong NS, et al: A questionnaire based survey on prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema in five Chinese cities (ISAAC study). (Article in Chinese). Chin J Pediatr. 1998, 36: 352-355.

Zhao TB, Wang HJ, Chen Y, Xiao M, Duo L, Liu G, et al: Prevalence of childhood asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema in Urumqi and Beijing. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000, 36: 128-133. 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2000.00457.x.

Ma Y, Zhao J, Han ZR, Chen Y, Leung TF, Wong GW: Very low prevalence of asthma and allergies in schoolchildren from rural Beijing, China. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009, 44: 793-799. 10.1002/ppul.21061.

Wang HY, Zheng JP, Zhong NS: Time trends in the prevalence of asthma and allergic diseases over 7 years among adolescents in Guangzhou city. (Article in Chinese). Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006, 86: 1014-1020.

Yangzong , Nafstad P, Madsen C, Bjertness E: Childhood asthma under the north face of Mount Everest. J Asthma. 2006, 43: 393-398. 10.1080/02770900600710326.

Droma Y, Kunii O, Yangzom Y, Shan M, Pingzo L, Song P: Prevalence and severity of asthma and allergies in schoolchildren in Lhasa, Tibet. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007, 37: 1326-1333. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02781.x.

Wong GW, Li ST, Hui DS, Fok TF, Zhong NS, Chen YZ, et al: Individual allergens as risk factors for asthma and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in Chinese children. Eur Respir J. 2002, 19: 288-293. 10.1183/09031936.02.002319.02.

*Chen YZ: A nationwide survey in China on prevalence of asthma in urban children. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Pediatr. 2003, 41: 123-127.

*Yan CR, Li JY, Liu L, Lu ZY, Zhang GZ: Epidemiological survey on childhood asthma and respiratory infection in a rural area of Cangzhou. (Article in Chinese). J Appl Clin Paediatr. 1994, 9: 28-29.

*Zheng LL, Ni C, Liu ZM, Gan XY, Ji MH, Yang CF: The present situation of asthma among 0 to 14 years old children in Hefei of Anhui province. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Prev Contr Chron Non-commun Dis. 2003, 11: 260-262.

*Hao CL, Zhang JH, Yang YD, Sheng JY, Yang YS: Epidemiological survey on children's asthma in Suzhou. (Article in Chinese). Suzhou Univ J Med Science. 2002, 22: 153-156.

Wu ZZ, Shen XM, Xu LP, Wang X: Survey on prevalence of bronchial asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in urban area of Haining. (Article in Chinese). Zhejiang Clin Med J. 2003, 5: 637-638.

*Cooperation Group of Children's Asthma in Liaoning Shenyang (CGCALS): A study on incidence of bronchial asthma and related factors in children 0-14 years of age in Liaoning. (Article in Chinese). Pediatr Emerg Med. 2002, 9: 11-13.

Cooperative Research Group on Childhood Asthma in Gansu Province (CRGCAGP): Epidemiological survey on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Lanzhou. (Article in Chinese). J Lanzhou Med Coll. 1992, 18: 190-192.

Jiang DZ, Yao L, Lu LJ, Yang GS, Mai QL, Yu B: Epidemiological survey on childhood asthma among 40,000 children in Guangxi Province. (Article in Chinese). Guangxi Med J. 1993, 15: 162-164.

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Lhasa, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lhasa. Last modified 11 Sep 2011

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Xining, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xining. Last modified 23 Aug 2011

*Chen YZ, Li Y, Liu SY, Li DW, Gong MM, Zhang ZJ: Beijing area survey on bronchial asthma 40 thousand children. (Article in Chinese). Beijing Med J. 1995, 17: 1-4.

*Kong Y, Ren CY, Cheng YJ, Yang A, Wang LZ, Xia JH: Epidemiological study on the sickness rate of asthma in children of 0 to 14 years old in urban area of Huainan. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Child Health Care. 2006, 14: 295-296.

*Wang Y, Wu SG, Pan XJ, Zhu JL, Huang ZL: The investigation and study of children's bronchial asthma of epidemiology in Nanhai. (Article in Chinese). Guide of China Medicine. 9, 9: 30-31.

*Han LS, Shen L, Qiu WJ, Wang L, Zhang FJ, Zhang CY: Epidemiology of childhood asthma in Huangpu District of Shanghai. (Article in Chinese). Acad J Sec Mil Med Univ. 2002, 23: 1255-1257.

Hong JX, Wang XY, Meng GJ, Wang LP, Wu HF: Epidemiological survey of bronchial asthma among 0 to 14 years old children in Xiaoshan city. (Article in Chinese). Zhejiang J Inte Tra Wes Med. 2000, 10: 187-189.

Cooperative Research Group on Childhood Asthma at Children's Hospital in Suzhou Medical College (CRGCACHSMC): Epidemiological survey on childhood asthma in Suzhou. (Article in Chinese). Acta Acad Med Suzhou. 1995, 15: 195-196.

*Wang SY, Ding H, Wang SQ: Survey on prevalence rate of children with asthma in Zaozhuang City in 2004. (Article in Chinese). Mod Prev Med. 2007, 34: 83-84-100.

*Cen SN, Gong YN, Wei GQ, Wu Q, Chen JL: Survey on prevalence rate of asthma in children in Foshan city. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Chil Health Care. 2005, 13: 219-221.

Respiratory Research Group on Paediatrics of the Shanghai Medical Committee (RRGPSMC): Investigation on asthma among children aged 0 to14 years using cluster sampling method in Shanghai City. (Article in Chinese). J Clin Pediatr. 1994, 12: 107-109.

Chen SH, Qiu SQ, Yang XQ, Wu C, Xia W: Epidemiological survey on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in the Jiangsu Province. (Article in Chinese). Jiangsu Med J. 1993, 19: 376-377.

Tang PW, Fang YP, Xie WZ, Tang SP: Epidemiological survey on childhood bronchial asthma in Zhejiang Province. (Article in Chinese). Zhejiang Med J. 1993, 15: 57-60.

Cooperative Research Group on Childhood Asthma in Xinjiang (CRGCAX): Epidemiological survey on chidhood bronchial asthma in Xinjiang. (Article in Chinese). Xinjiang Med J. 1995, 25: 40-42.

Guo LC, Hu LR, Xie ZH, Shen BR, Yu HH: Epidemiological survey on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Ningxia. (Article in Chinese). Inte Med J. 1992, 27: 40-42.

*Chen P, Yu RH, Hou XM, Tan PQ, Xie H, Kong LF, et al: Epidemiological survey on bronchial asthma in Liaoning province. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis. 2002, 25: 603-606.

Cooperative Research Group on Asthma in Sichuan Province(CRGASP): Epidemiological survey on childhood asthma in Sichuan. (Article in Chinese). Chongqing Med J. 1992, 21: 191-192-60.

Cooperative Research Group on Childhood Asthma in Anqing City (CRGCAAC): Epidemiological survey on asthma among 10,000 children aged 0 to 14 years in Anqing City. (Article in Chinese). Acta Univ Med Anhui. 2002, 37: 241-242.

Cooperative Research Group on Childhood Asthma in Lhasa City (CRGCALC): An epidemiological study on asthma among Tibetan children aged 0 to 14 years in Lhasa. (Article in Chinese). Tibet Med J. 1994, 15: 37-39.

Cooperative Research Group on Childhood Asthma in Tianjin City (CRGCATC): Epidemiological survey on asthma among 20,000 children aged 0 to 14 years in Tianjin City. (Article in Chinese). Tianjin Med J. 1991, 10: 607-609.

Feng YZ, Ma PR, Han XZ: Prevalence and epidemilogic characters of asthma in Shandong Province. (Article in Chinese). Acta Acad Med Shandong. 1994, 32: 212-215.

He QN, Liu JM, Cao Y, Huang DL, Hu JT, Yi ZW: Epidemiological study on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Changsha City in 2000. (Article in Chinese). Hunan Med J. 2001, 18: 364-365.

*Li CC, Cai XH, Hu XG, Luo YC, Dong L, Li MR, et al: Epidemiological survey of bronchial asthma in children of Wenzhou city in the year 2000. (Article in Chinese). J Wenzhou Med Coll. 2003, 32: 12-14.

Li HW, Han DC, Zhang WJ, Cai P, Yang HL: Epidemiological survey on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Zhanggong District of Bengbu. (Article in Chinese). J Bengbu Med Coll. 1993, 18: 47-48.

Li J, Zhang Y: Investigation on prevalence of asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Zunyi City. (Article in Chinese). Guizhou Med J. 2002, 26: 1047-1048.

*Li XD, Li L, Wu XY, Liu SF, Zhang WJ, Zhang M, et al: Epidemiological survey on bronchial asthma among urban population in Kaifeng City. (Article in Chinese). J Henan Unive (Med Sci). 2006, 25: 41-42.

Lin LY, Xu PC, Wu JC: Survey on prevalence of asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Zhaoan County. (Article in Chinese). Fujian Med J. 1995, 17: 115-116.

Lin RC, Tian Q, Le X, Su ZW: Epidemiological survey on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Nanshan District of Shenzhen City. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Child Health Care. 2005, 13: 154-155.

*Lin RJ, Lu XF, Shan PF, Yuan GX, Wang JY, Wang SM: Epidemiological survey of children asthma in Qingdao District. (Article in Chinese). Acta Aca Med Qingdao. 1993, 29: 142-146.

*Lin RJ, Wang WD, Pan YJ, Sun XF, Guan RM: An epidemiological survey of 0 −14 year-old children with asthma in Qingdao City proper. (Article in Chinese). Acta Acad Med Qingdao. 2002, 38: 202-205.

*Liu H, Ji YS, Gu JH: Epidemiology investigation of infantile bronchial asthma in Baoshan district of Shanghai. (Article in Chinese). Hebei Med J. 2001, 23: 813-815.

Liu L, Li T, Liu WT: An epidemiological study on asthma in Zhengzhou City in 2000. (Article in Chinese). Henan J Prev Med. 2001, 12: 164-165.

*Liu L, Lu JR, Cheng HJ, Qiao HM, Zhao KM, Zou YX, et al: Survey analysis of 0−14 years old children with asthma in Changchun city. (Article in Chinese). J Jilin Univ (Med Edi). 2005, 31: 149-151.

Liu SM, Wang XX, Liang QQ, Wang W, Dong CF: Epidemiological study on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Shaoxing. (Article in Chinese). J Pract Med. 2006, 22: 2546-2547.

*Lu WQ, Wang YF, Li B, Ai R, Cui YX, Yang B, et al: A survey and analysis on children's asthma of Guiyang City in 2000. (Article in Chinese). J Guiyang Med Coll. 2002, 27: 231-234.

Peng YL, Tang BX, Liu JG, Zhen XA, Wang CH, Wang GB: Epidemiological survey on bronchial asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Henan Province. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Epidemiol. 2001, 22: 470-471.

Ping W, Ma RC, Zhu JY, Li GY, Yang ZD, Guo XJ, et al: Epidemiological survey on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Xining. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Chil Health Care. 2004, 12: 440-441.

Ren X, Wang LJ, Li ZL, Tian YZ, Ma CL, Xie Q: An epidemiological survey on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Shanxi Province. (Article in Chinese). Shanxi Med J. 2004, 33: 88-90.

Song YJ, Li J, Wang KL, Liu L, Xu BY, Tian J, et al: An epidemiological survey of asthma in 0−14 year-old children in Hebei province. (Article in Chinese). Hebei Med J. 2001, 23: 485-486.

Southern China Cooperative Research Group on Childhood Asthma (SCCRGCA): Epidemiological survey on childhood asthma in the South and Southwestern parts of China. (Article in Chinese). J Pract Pediatr. 1993, 8: 104-106.

*Sun LB, Wang YT, Wan WJ, Ren HL, Gu AL: Epidemiological investigation on children under 14 years old with asthma in Chaohu City. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2008, 12: 498-500.

Tang PW, Tang SP, Jia TM: Epidemiological survey on asthma among 20,000 children aged 0 to 14 years in Hangzhou City. (Article in Chinese). Zhejiang J Prev Med Dis Monit. 1992, 4: 10-11.

*Wang CL, Wang M, Luo RH, Lu ZR, Li M, Li L, et al: Epidemiological survey of asthma in Chengdu urban district. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Child Health Care. 2003, 11: 32-34.

*Wang LJ, Ren XM, Tian YZ, Ma CL, Xie Q: Epidemiological investigation of asthma in children aged 0−14 years old in Xian city. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Matern Child Health Res. 2007, 18: 88-89.

*Wang LS, Wang LS, Li Y, Tan Y, Cai GX, Jiang C, et al: An epidemiologic survey of prevalence of asthma among 30,682 children in Zunyi District of Guizhou Province. (Article in Chinese). J Zunyi Med Coll. 1992, 15: 1-5.

Wang SF, Yu DY, Xu L: Epidemiological survey on bronchial asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Jiangxi Province. (Article in Chinese). J Jiangxi Coll Tradi Chin Med. 1992, 4: 34-35-48.

Wei XJ, Li MX, Jiao P, Ma SX: Survey on childhood bronchial asthma in Beilin district of Xian City. (Article in Chinese). Lanhou Health. 1993, 14: 43-

Wu JZ, Zhong SH, Shen YH, Chen Q, Zhao LP, Fang M, et al: Epidemiological survey on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Xiamen City. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Child Health Care. 2002, 10: 48-49.

*Xiao HL, Huang H, Feng XB, Xu SZ, Fu ZR, Wu ZL, et al: An investigation of children asthma in Binzhou area. (Article in Chinese). J Binzhou Med Coll. 1992, 15: 215-217-86.

*Xu BY, Li J, Liu XZ, Feng QA, Wu HQ, Wang LH: Study on incidence of bronchial asthma and related factors in children 0-14 years of age in Handan. (Article in Chinese). J Handan Med Coll. 2002, 15: 577-579.

*Yang JZ, Zheng JY, Su MY, Zhuo ZQ, Chen ZH: Correlation factors of asthma survey in Quanzhou city. (Article in Chinese). Fujian Med J. 2006, 28: 151-152.

Yao J, Ding S, Wang CH, Ge CS, Zhang BZ, Wu L, et al: Investigation on prevalence of asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Nanjing City. (Article in Chinese). Acta Unive Med Nanjing. 2002, 22: 61-63.

Yu B: Epidemiological survey on asthma among 10,000 children aged 0 to 14 years in Nanning City. (Article in Chinese). Anthology Med. 1999, 18: 244-245.

Zhao SW, Wang WG, Lu AP, Wang J, Liu XQ: Survey on prevalence of asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Taiyuan City. (Article in Chinese). Chin Prim Health Care. 2002, 16: 32-33.

Zhao YN, Lu PG, Li WJ, Zhang F, Li Q, Tian J, et al: Epidemiological investigation on asthma among children aged 0 to 14 years in Baoji City. (Article in Chinese). Chin J Child Health Care. 2003, 11: 283-284.

Ellwood P, Williams H, Ait-Khaled N, Bjorksten B, Robertson C: Translation of questions: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) experience. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009, 13: 1174-1182.

Magnus P, Jaakkola JJ: Secular trend in the occurrence of asthma among children and young adults: critical appraisal of repeated cross sectional surveys. BMJ. 1997, 314: 1795-1799. 10.1136/bmj.314.7097.1795.

Abba K, Clarke S, Cousins R: Assessment of the potential effects of population changes in attitudes, awareness and beliefs on self-reporting of occupational ill-health. Occup Med (Lond). 2004, 54: 238-244. 10.1093/occmed/kqh038.

Zielinski J, Bednarek M, Gorecka D, Viegi G, Hurd SS, Fukuchi Y, et al: Increasing COPD awareness. Eur Respir J. 2006, 27: 833-852. 10.1183/09031936.06.00025905.

Schernhammer ES, Vutuc C, Waldhor T, Haidinger G: Time trends of the prevalence of asthma and allergic disease in Austrian children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008, 19: 125-131. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00597.x.

Mvula M, Larzelere M, Kraus M, Moisiewicz K, Morgan C, Pierce S, et al: Prevalence of asthma and asthma-like symptoms in inner-city schoolchildren. J Asthma. 2005, 42: 9-16. 10.1081/JAS-200044746.

Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Fenn M, Twiselton R, Matthews S, Arshad SH: The prevalence of asthma and wheezing illnesses amongst 10-year-old schoolchildren. Respir Med. 2002, 96: 163-169. 10.1053/rmed.2001.1236.

Wang XS, Tan TN, Shek LP, Chng SY, Hia CP, Ong NB, et al: The prevalence of asthma and allergies in Singapore; data from two ISAAC surveys seven years apart. Arch Dis Child. 2004, 89: 423-426. 10.1136/adc.2003.031112.

Wang YJ: Bellamy urges Tibet to reach for new heights for children. 2006, http://tibet.cn/en/newfeature/un/news/t20060118_85717.htm. Data last updated 18 Jan 2006

United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation: Levels and trends in child mortality: 2010 report. http://www.unicef.org/media/files/UNICEF_Child_mortality_for_web_0831.pdf,

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/860/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Doctor Yeshi Yangzom for her encouragement and support, and Carol Knudsen and Theresia Hofer for the English revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The authors' responsibilities were as follows Yz: Coordinated the literature review and assessment of review and wrote the manuscript; ZS: contributed in literature review and assessment of review and participated in developing of the manuscript; PN: contributed to the writing of the manuscript; LLH: participated in developing of the manuscript, especially in the methodology part of the manuscript; OL: logistical support for literature review in Tibet; EB: contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12889_2012_4662_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Table S1. Characteristics of included studies--- Prevalence of childhood asthma among 0−14 year-old children in 1990 and 2000. (DOC 148 KB)

12889_2012_4662_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Table S2. Characteristics of included studies--- Prevalence of childhood asthma among 0−14 years old children (uncertain whether it is current or lifetime prevalence). (DOC 67 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yangzong, Y., Shi, Z., Nafstad, P. et al. The prevalence of childhood asthma in China: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 12, 860 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-860

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-860