Abstract

Background

The prevalence of obesity is rising in Scotland and globally. Overall, obesity is associated with increased morbidity, mortality and reduced health-related quality of life. Studies suggest that "healthy obesity" (obesity without metabolic comorbidity) may not be associated with morbidity or mortality. Its impact on health-related quality of life is unknown.

Methods

We extracted data from the Scottish Health Survey on self-reported health-related quality of life, body mass index (BMI), demographic information and comorbidity. SF-12 responses were converted into an overall health utility score. Linear regression analyses were used to explore the association between BMI and health utility, stratified by the presence or absence of metabolic comorbidity (diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular disease), and adjusted for potential confounders (age, sex and deprivation quintile).

Results

Of the 5,608 individuals, 3,744 (66.8%) were either overweight or obese and 921 (16.4%) had metabolic comorbidity. There was an inverted U-shaped relationship whereby health utility was highest among overweight individuals and fell with increasing BMI. There was a significant interaction with metabolic comorbidity (p = 0.007). Individuals with metabolic comorbidty had lower utility scores and a steeper decline in utility with increasing BMI (morbidly obese, adjusted coefficient: -0.064, 95% CI -0.115, -0.012, p = 0.015 for metabolic comorbidity versus -0.042, 95% CI -0.067, -0.018, p = 0.001 for no metabolic comorbidity).

Conclusions

The adverse impact of obesity on health-related quality of life is greater among individuals with metabolic comorbidity. However, increased BMI is associated with reduced health-related quality of life even in the absence of metabolic comorbidity, casting doubt on the notion of "healthy obesity".

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), more than one in ten of the world's adult population are obese [1]. In Scotland, around two-thirds of adult men and more than one-half of adult women are either overweight or obese (http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Health/TrendObesity) and, in common with other developed countries, the prevalence is increasing. Overall, obesity is associated with an increased risk of many conditions including hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease [2–5]. It is also associated with reduced life-expectancy [6–9]. There is growing evidence that the association between obesity and fatal or non-fatal events is mediated via these other conditions and that isolated obesity may not be injurious to health. In the United States of America, around 29% of obese men and 45% of obese women (totalling 19.5 million individuals) do not have metabolic comorbid conditions [10]. They do not appear to be at increased risk of cardiovascular events [11], and it has been suggested that weight loss will not be beneficial and may even increase their risk of cardio-metabolic outcomes [10–15]. This had led to the term "healthy obesity." Overall, obesity is associated with anxiety, depression and impaired health-related quality of life [16–19]. Previous research suggests that deterioration in health-related quality of life in overweight and obese individuals may be due to the presence of comorbidity [20]. It is currently unknown whether isolated or "healthy" obesity is associated with the decline in health-related quality of life. In this study, we used data from a Scotland-wide survey to address this question by comparing the health-related quality of life across the BMI category of people in the presence and absence of metabolic comorbidity.

Methods

Data source

The Scottish Health Survey has been conducted at regular intervals, of 3-5 years, since 1995. The Survey uses multi-stage, stratified probability sampling to ensure a representative sample of the general population. The trained staff collected data via face to face interview (including age, sex, postcode of residence, lifestyle risk factors, medication, past medical history and current health) and measured weight, height and blood pressure and obtained blood samples for assays (including total cholesterol concentrations) (http://www.esds.ac.uk/government/shes/). We used an extract of data from the 2003 Survey, the focus of which was cardiovascular disease and risk factors.

Inclusion criteria and definitions

Our analyses were restricted to participants aged ≥ 20 years and those included were categorised into three age groups: 20-44, 45-64 and ≥ 65 years. Postcode of residence was used to allocate individuals to a socioeconomic quintile of the general population using the 2004 Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) (http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2005/01/20458/49127). The index is derived from 31 markers of deprivation relating to health, education, housing, current income, employment access and crime, that are applied to each postcode data zones. There are 6,505 data zones in Scotland with a mean population of 750. Body Mass Index (BMI) was categorised according to the World Health Organisation definition [21]: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9 40 kg/m2), and obese (BMI 30.0-39.9 kg/m2), with the addition of a category for morbidly obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2). Metabolic comorbidity was defined as the presence of one or more of the following conditions known to be associated with obesity: diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia or cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular disease was defined as angina or a past history of stroke or myocardial infarction and was based on participants reporting diagnosis by a doctor. Hypertension was defined as a blood pressure measurement of ≥ 140/90 mmHg, or anti-hypertensive medication. Hypercholesterolaemia was defined as a total cholesterol concentration ≥ 5.2 mmol/L, or lipid-lowering medication. Smoking status was self-reported and classified as never, ex- or current smoker. Alcohol consumption was self-reported and categorised as never, ex-, sensible and excessive, with the cut-off between sensible and excessive drinking defined as more than 14 units/week for women and 21 units/week for men [20] The responses obtained from the SF-12 questionnaires were converted into a single utility score using an algorithm developed by Brazier and colleagues at the University of Sheffield (http://www.shef.ac.uk/scharr/sections/heds/mvh/sf-6d/revisions.html) [22].

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 11.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). Categorical data were summarized using frequencies and percentages and groups were compared using chi-square tests, or chi-square tests for trend for ordinal data. We used univariate and multivariate linear regression models to examine the association between BMI category and utility score, adjusting for the potential confounding effects of age, sex, deprivation quintiles, smoking status and alcohol consumption. Normal weight was used as the referent category. We tested whether there was a statistically significant interaction with metabolic comorbidity and stratified the analyses by the presence of metabolic comorbidity. The robustness of standard errors was checked using the bootstrapping method.

Results

Of the 10,470 individuals who participated in the Scottish Health Survey, 7,097 were aged ≥ 20 years. Of these 6,559 (92%) had sufficient data to calculate a utility score. Participants who completed the SF-12 instrument were not significantly different in terms of BMI category (p = 0.225) and sex (p = 0.197), but were younger (p < 0.001), less socioeconomically deprived, (p < 0.001), and more likely to have metabolic comorbidity (p < 0.001). Among the 6,559 participants with a utility score, 5,608 (86%) also had BMI recorded and they comprised the study population. These individuals were not significantly different in term of metabolic comorbidity (p = 0.582) but were younger (p < 0.001), more likely to be male (p < 0.001) and less socioeconomically deprived (p = 0.020).

Of the 5,608 individuals, 2,531 (45.1%) were men and the mean age was 50 years (standard deviation 16 years). Nine hundred and twenty one (16.4%) had metabolic comorbidity and the mean utility score was 0.80 (standard deviation 0.14). One thousand seven hundred and ninety seven (32.0%) were normal weight, 2,276 (40.6%) overweight, 1,319 (23.5%) obese, 149 (2.7%) morbidly obese, and 67 (1.2%) underweight. There were significant differences between the BMI categories in terms of age and sex (Table 1). The percentage belonging to the most deprived quintile increased significantly from normal weight to morbidly obese, as did the percentage with metabolic comorbidity (Table 1).

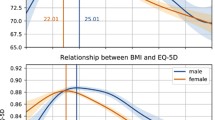

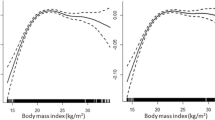

In relation to the association between BMI category and utility score, there was a significant interaction with metabolic comorbidity (p = 0.007). In every BMI category, the utility score was lower among those with metabolic comorbidity (Figure 1). Among both individuals with and without metabolic comorbidity, there was an inverted U-shaped relationship whereby health utility was highest among overweight individuals and fell with increasing BMI, with the decline steepest among those with metabolic comorbidity (Figure 1). Health related-quality of life was significantly reduced among obese individuals regardless of the presence or absence of metabolic comorbidity. After adjustment for the potential confounding effects of age, sex, deprivation smoking status and alcohol consumption, the utility score was non-significantly higher among overweight than normal weight individuals, irrespective of the presence of metabolic comorbidity (Table 2). Compared with normal weight individuals, utility scores were significantly lower among both morbidly obese and underweight individuals in both groups (Table 2).

Discussion

Individuals with metabolic comorbidity have a poorer health-related quality of life than those without, irrespective of their BMI. However, health-related quality of life is significantly reduced among obese individuals even in the absence of metabolic comorbidity, suggesting that "healthy obesity" is a misnomer. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated reduced health-related quality of life among obese individuals [17, 18, 23–28]. However, these studies have only considered obese individuals as a whole. Historically, normal weight was associated with the lowest risk of cardiovascular diseases and type II diabetes, and the highest health-related quality of life [17, 29]. This has changed over time, and our finding of non-significantly higher health-related quality of life among overweight individuals is consistent with other recent studies [28, 30–32]. Previous studies have also shown poorer health among individuals with a low BMI [28, 33, 34]. This is likely to be due, in part, to reverse causation due to conditions other than those that we included in our definition of metabolic comorbidity.

There is a growing consensus that the increased risk of cardiometabolic events associated with obesity is mediated, largely, via the increased risk of intermediate conditions such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and type II diabetes [21]. A number of studies have identified a sub-group of obese individuals who do not develop these intermediate conditions [11]. They are not at significantly increased risk of cardiometabolic events, and weight loss does not improve their natural history [10–15]. These findings have led to the label "healthy" obesity.

Health extends beyond clinical events, to encompass psychological well-being. A number of studies have shown that health-related quality of life is reduced among obese individuals [35–38]. It was not previously known whether, as with clinical events, this risk was specific to obese individuals with metabolic comorbidity. Our study demonstrated that, whilst health-related quality of life was lower among individuals with metabolic comorbidity, it was nonetheless significantly reduced among obese individuals with no metabolic comorbidity.

The study used data from a large pan-Scotland survey representative of the general population. Due to incomplete data on BMI or utility score in 14% of participants, the study population was younger, more affluent and healthier than the overall survey population. However, this is unlikely to affect the generalisability of the results. Access to information on metabolic comorbidity enabled us to undertake sub-group analyses. BMI and blood pressure measurements were made by trained fieldworkers using standard operating procedures and the presence of hypercholesterolemia was based on blood assays. Presence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease were based on clinician diagnosis but reported by participants. Since the study was conducted retrospectively, this is unlikely to have led to reporting bias. In a cross-sectional study, a temporal relationship cannot be established. Therefore, reverse causation is possible. This is particularly so among individuals who are below normal weight in whom other conditions may be causing both poor health-related quality of life and weight loss. Survival bias may also occur in cross-sectional studies. Our findings should be corroborated within the context of a cohort study.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that obesity is not only a risk for fatal and non-fatal clinical events but also reduced health-related quality of life, even in the absence of comorbid conditions. Our findings cast doubt on the notion of "healthy" obesity and reinforce the need for population and individual interventions to reverse the increasing prevalence of obesity.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- N:

-

number.

References

World Health Organization: Obesity and overweight. 2012, [http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html]

Colditz GA: Economic costs of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992, 55: 503-507.

Rippe JM, Crossley S, Ringer R: Obesity as a chronic disease: modern medical and lifestyle management. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998, 98: 9-15.

Bray GA: Pathophysiology of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992, 55: 488-494.

Trakas K, Lawrence K, Shear NH: Utilization of health care resources by obese Canadians. CMAJ. 1999, 160: 1457-1462.

Olshansky SJ, Passaro DJ, Hershow RC, Layden J, Carnes BA, Brody J, et al: A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. N EnglJ Med. 2005, 352: 1138-1145. 10.1056/NEJMsr043743.

Hu FB, Willett WC, Li T, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE: Adiposity as compared with physical activity in predicting mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351: 2694-2703. 10.1056/NEJMoa042135.

Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH: Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005, 293: 1861-1867. 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861.

Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Al MA, Bonneux L, et al: Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: A life-table analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003, 138: 24-32.

Wildman RP, Muntner P, Reynolds K, McGinn AP, Rajpathak S, Wylie-Rosett J, et al: The obese without cardiometabolic risk factor clustering and the normal weight with cardiometabolic risk factor clustering: prevalence and correlates of 2 phenotypes among the US population (NHANES 1999-2004). Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168: 1617-1624. 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1617.

Wildman RP: Healthy obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metabo Care. 2009, 12: 438-443. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32832c6db7.

Sims EA: Are there persons who are obese, but metabolically healthy? Erratum appears in Metabolism. Metabolism. 2001, 50: 1499-1504. 10.1053/meta.2001.27213.

Stefan N, Kantartzis K, Machann J, Schick F, Thamer C, Rittig K, et al: Identification and characterization of metabolically benign obesity in humans. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168: 1609-1616. 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1609.

Velho S, Paccaud F, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Marques-Vidal P: Metabolically healthy obesity: Different prevalences using different criteria. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010, 64: 1043-1051. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.114.

Iacobellis G, Ribaudo MC, Zappaterreno A, Iannucci CV, Leonetti F: Prevalence of uncomplicated obesity in an Italian obese population. Obes Res. 2005, 13: 1116-1122. 10.1038/oby.2005.130.

Morrison DS, Boyle S, Morrison C, Allardice G, Greenlaw N, orde L: Evaluation of the first phase of a specialist weight management programme in the UK National Health Service: prospective cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2011,

Fontaine KR, Barofsky I: Obesity and health-related quality of life. Obes reviews: an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2001, 2: 173-182.

Kolotkin RL, Meter K, Williams GR: Quality of life and obesity. Obes Rev. 2001, 2: 219-229. 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2001.00040.x.

Jia H, Lubetkin EI: The impact of obesity on health-related quality-of-life in the general adult US population. J Public Health. 2005, 27: 156-164. 10.1093/pubmed/fdi025.

Doll HA, Petersen SE, Stewart-Brown SL: Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obes Res. 2000, 8: 160-170. 10.1038/oby.2000.17.

World Health Organization: 2000, Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO consultation

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M: The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Economics. 2002, 21: 271-292. 10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00130-8.

Yan LL, Daviglus ML, Liu K, Pirzada A, Garside DB, Schiffer L, et al: BMI and health-related quality of life in adults 65 years and older. Obes Res. 2004, 12: 69-76. 10.1038/oby.2004.10.

Hassan MK, Joshi AV, Madhavan SS, Amonkar MM: Obesity and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional analysis of the US population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003, 27: 1227-1232. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802396.

Castres I, Folope V, Dechelotte P, Tourny-Chollet C, Lemaitre F: Quality of life and obesity class relationships. Int J Sports Med. 2010, 31: 773-778. 10.1055/s-0030-1262830.

Garcia-Mendizabal MJ, Carrasco JM, Perez-Gomez B, Aragones N, Guallar-Castillon P, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, et al: Role of educational level in the relationship between Body Mass Index (BMI) and health-related quality of life (HRQL) among rural Spanish women. BMC Public Health. 2009, 9: 120-10.1186/1471-2458-9-120.

Ford ES, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Mokdad AH, Chapman DP: Self-reported body mass index and health-related quality of life: findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Obes Res. 2001, 9: 21-31. 10.1038/oby.2001.4.

Hopman WM, Berger C, Joseph L, Barr SI, Gao Y, Prior JC, et al: The association between body mass index and health-related quality of life: data from CaMos, a stratified population study. Qual Life Res. 2007, 16: 1595-1603. 10.1007/s11136-007-9273-6.

Friedman MA, Brownell KD: Psychological correlates of obesity: moving to the next research generation. Psychol Bull. 1995, 117: 3-20.

Bentley TG, Palta M, Paulsen AJ, Cherepanov D, Dunham NC, Feeny D, et al: Race and gender associations between obesity and nine health-related quality-of-life measures. Qual Life Res. 2011, 20: 665-674. 10.1007/s11136-011-9878-7.

Lopez-Garcia E, Banegas Banegas JR, Gutierrez-Fisac JL, Perez-Regadera AG, Ganan LD, Rodriguez-Artalejo F: Relation between body weight and health-related quality of life among the elderly in Spain. IntJ Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003, 27: 701-709. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802275.

Vasiljevic N, Ralevic S, Marinkovic J, Kocev N, Maksimovic M, Milosevic GS, et al: The assessment of health-related quality of life in relation to the body mass index value in the urban population of Belgrade. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008, 6: 106-10.1186/1477-7525-6-106.

Sach TH, Barton GR, Doherty M, Muir KR, Jenkinson C, Avery AJ: The relationship between body mass index and health-related quality of life: comparing the EQ-5D, EuroQol VAS and SF-6D. Int J Obes. 2007, 31: 189-196. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803365.

Wee HL, Cheung YB, Loke WC, Tan CB, Chow MH, Li SC, et al: The association of body mass index with health-related quality of life: an exploratory study in a multiethnic Asian population. Value Health. 2008, 11: 105-114.

Fontaine KR, Barofsky I: Obesity and health-related quality of life. Obes Rev. 2001, 2: 173-182. 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00032.x.

Kushner RF, Foster GD: Obesity and quality of life. Nutrition. 2000, 16: 947-952. 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00404-4.

Friedman MA, Brownell KD: Psychological correlates of obesity: moving to the next research generation. PsycholBull. 1995, 117: 3-20.

Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Stunkard A, Rissanen A: Psychosocial factors and quality of life in obesity. IntJ Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995, 19: 1-5.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/143/prepub

Acknowledgements

ZUH is sponsored under the Higher Education Commission, Pakistan funded project titled "Development of Khyber Medical University, Peshawar".

Funding

No external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JPP had the original concept. All of the authors agreed the methodology. ZUH and DFM performed the statistical analyses. All authors interpreted the results. ZUH drafted the manuscript. All authors fed back comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ul-Haq, Z., Mackay, D.F., Fenwick, E. et al. Impact of metabolic comorbidity on the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life: a Scotland-wide cross-sectional study of 5,608 participants. BMC Public Health 12, 143 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-143

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-143