Abstract

Background

Social support has proved to be one of the most effective factors on the success of diabetic self-care. This study aimed to develop a scale for evaluating social support for self-care in middle-aged patients (30–60 years old) with type II diabetes.

Methods

This was a two-phase qualitative and quantitative study. The study was conducted during 2009 to 2011 in Tehran, Iran. In the qualitative part, a sample of diabetic patients participated in four focus group discussions in order to develop a preliminary item pool. Consequently, content and face validity were performed to provide a pre-final version of the questionnaire. Then, in a quantitative study, reliability (internal consistency and test-retest analysis), validity and factor analysis (both exploratory and confirmatory) were performed to assess psychometric properties of the scale.

Results

A 38-item questionnaire was developed through the qualitative phase. It was reduced to a 33-item after content validity. Exploratory factor analysis loaded a 30-item with a five-factor solution (nutrition, physical activity, self monitoring of blood glucose, foot care and smoking) that jointly accounted for 72.3% of observed variance. The confirmatory factor analysis indicated a good fit to the data. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient showed excellent internal consistency (alpha=0.94), and test-retest of the scale with 2-weeks intervals indicated an appropriate stability for the scale (ICC=0.87).

Conclusion

The findings showed that the designed questionnaire was a valid and reliable instrument for measuring social support for self-care in middle-aged patients with type II diabetes. It is an easy to use questionnaire and contains the most significant diabetes related behaviors that need continuous support for self-care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

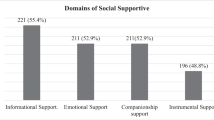

Diabetes is a worldwide health problem and the number of people with diabetes will exceed to 366 million in 2030 and mostly among middle-aged populations [1]. This widespread of the disease makes any health care systems unable to respond to the need of patients [2]. Thus, it is suggested that self-care in this context is essential [3]. Self-care is defined as ‘self-motivation, understanding and considering the situations that influence health, making decisions to improve health, and implementing these decisions’ [4]. However, there is no promise for self-care if we do not accurately recognize and evaluate the constructs that are affective on it. It has been suggested self-care needs some additive components such as social support to be maintained. It has been recommended that providing social support for self-care might have twofold advantages. Firstly, it could prevent the possible complications and secondly, could guarantee the continuity of the self-care behavior where self-management plays an important role in patients’ overall health status [5, 6]. Several self-care behaviors were recognized to improve health in diabetic patients. For instance, Mc Dowell et al. believe nutrition, physical activity, self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), and foot care as the main behaviors for self-care in patients with type II diabetes [7]. It is argued that these behaviors could not be achieved unless we provide appropriate social support for patients [8, 9]. However, as there are many types of social support [10, 11], patients with diabetes also could receive different types of support for self-care such as informational, emotional and instrumental [12–14].

Several studies examined the relationship between self-care and social support in patients with diabetes [9, 15, 16]. The consistent findings from the literature were that patients with diabetes did not receive enough social support from families and professionals and when they received such supports, they showed improved self-care behaviors [17, 18]. Yet, the main critic with previous studies relies on the fact that similar measures were used to assess social support for patients with different demographic backgrounds while, for instance, providing social support for young diabetic patients could be different from providing social support for elderly patients. Even, in a study, it was found that older adolescents have obtained less family support than younger ones, and older girls reported the highest level of support from their friends but the highest level of family support was for younger boys [19].

Therefore, the preliminary aim of this study was to develop a tailored measure for self-care social support. Since most diabetic patients are in the middle years of their lives, we thought to tailor an instrument for this age group. In brief, tailoring is a very useful psychological and social approach that could enhance health behaviors in target population [20]. Hawkins et al. refer tailoring to a number of methods for creating individualized communications that will lead to larger intended effects of these communications [21]. In addition, it was found that existing measures for self-care social support had no focus on all behaviors or included only a specific type of social support. Accordingly, the second aim of this study was to develop a comprehensive instrument that includes all forms of support for at least five recommended self-care behaviors that needs social support.

Methods

Scale development

This was a study to develop an instrument to measure social support for self-care in diabetic patients. Evidence suggests that social support makes people in general and patients in particular more able to care about themselves and maintain healthy behaviors. Social support can come from a variety of sources and is defined as the help one receives from family, friends, and significant others (such as physicians) [12, 22].

Several procedures were followed to provide an item pool for the study:

-

i.

A review of the literature.

-

ii.

A small-scale qualitative study was conducted to explore what does ‘social support for self-care’ mean to diabetic patients. For the purpose of qualitative phase, four focus group discussions were conducted with a sample of diabetic patients. Patients were recruited from diabetes screening centers affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences. We have tried to recruit patients with different characteristics to ensure that patients from diverse demographic backgrounds are present in the focus groups. In all, 38 patients agreed to take part in the study. The characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. All patients informed about the aim of the study and their informed consent was obtained. The discussions were hold in the screening center and all were tape-recorded. We stopped data collection until saturation was reached. Then, we transcribed group discussions and used a deductive method to analyze the data. Deductive content analysis is used when the structure of analysis is operationalized on the basis of previous knowledge [23]. Since we were concerned about five main self-care behaviors, the intention was to determine the frequency of sayings under five topics that were nutrition, physical activity, self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), foot care and smoking. Finally, a list of items was prepared with their examples. Trustworthiness of the results also was checked. As suggested four criteria were considered for the trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability [24]. For credibility, we designed clear processes for drawing conclusions from the data. For transferability, we provided rich enough descriptions and data sets that other researchers can use them in the other contexts and settings. For dependability, we checked the consistency of the study processes and finally, we checked the internal coherence of the data and the findings for confirmability [24].

-

iii.

Interview with a panel of experts: Experts were asked ‘What are the most important self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetics? Why these behaviors are so important? Why do you think the other behaviors are not as much important as your selected behaviors?’

At last, the data derived from the literature, the qualitative phase and interviews were crosschecked and in all 38 items were generated. Consequently content and face validity were evaluated.

Content validity: is a comprehensive review by an expert panel to decide whether items adequately cover the behavior that you are interested in measuring them [25]. It is an essential step for developing a scale and a mechanism for linking abstract concepts with tangible and measurable indicators [26]. The expert panel was consisted of 12 specialists in health education, nursing and internal medicine. Qualitative content validity was determined based on ‘grammar’, ‘wording’, ‘item allocation’, and ‘scaling’ indices [27]. All items were checked and the expert panel’s recommendations were inserted into the questionnaire. Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and Content Validity Index (CVI) were calculated in order to perform quantitative content validity. For calculating CVR, the expert panel was asked to evaluate each item using a 3-point Likert scale: 1 = essential, 2 = useful but not essential and 3 = unessential. Then, according to Lawshe’s table [28], items with CVR score of 0.56 or above were selected [27]. For the CVI, based on Waltz and Bausell [29] recommendation, the same panel was asked to evaluate the items according to a 4-point Likert scale on ‘relevancy’, ‘clarity’, and ‘simplicity’. A CVI score of 0.80 or above was considered satisfactory [30].

Face validity: is an evaluation of lay people in understanding and comprehending a scale [25]. In this part, both quantitative and qualitative methods were applied. For quantitative part, 10 patients were asked to evaluate the questionnaire and score the importance of each item on a 5-point Liker scale in order to calculate ‘Item Impact Score’ (Impact Score = Frequency (%) × Importance). The impact score of 1.5 or above was considered satisfactory as recommended [27]. For the qualitative part, the same patients were asked about the ‘relevancy’, ‘ambiguity’, and ‘difficulty’ of the items; and some minor changes were made to the preliminary questionnaire.

Pre-final version: following the reflection of the above approaches, finally 5 items were removed and the pre-final version of the questionnaire consisting of 33 items was provided for the next stages (validity and reliability of the questionnaire).

The main study and data collection

A cross sectional study was designed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the S4-MAD. A consecutive sample of the middle-aged patients with type II diabetes was recruited from two screening diabetes centers affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The patients were entered into the study if they were aged between 30 to 60 years, their last HbA1C test was equal or above 7% (or their FBS test was more than 150 mg/dl), having diabetes for more than 1 year, and wished to participate in the study.

Statistical analysis

Validity

The construct validity of the questionnaire was performed using both exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA).

-

a)

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA): A sample of 204 patients completed the questionnaire and its factor structure was extracted using the principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were used to assess the appropriateness of the sample for the factor analysis. Eigenvalues above 1 and scree plot were used for determining the number of factors. Factor loadings equal or greater than 0.4 were considered appropriate [31].

-

b)

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA): A separate sample of 138 patients completed the questionnaire and factor analysis was performed for assessing the model fitness. As recommended various fit indices including relative Chi-square (χ 2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were used [32]. Relative Chi-square is the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom and its recommended reference value is less than 3 for accepting the fitness of the model [33]. The value for CFI, IFI, NFI and NNFI could range between ‘0 to 1’ and values closer to 1 are indicative of data fitness [34]. An RMSEA ranged 0.08 to 0.10 shows a mediocre fit and below 0.08 indicates a good fit [35]. The acceptable value for SRMR is less than 0.10 where values less than 0.08 indicate adequate fit and values below 0.05 indicate good fit [36, 37].

Reliability

Internal consistency was evaluated by Cronbach’s α coefficient. Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.7 or above was considered satisfactory [38, 39]. In addition, a sub-sample of patients (n = 15) completed the questionnaire twice with a 2-weeks interval in order to examine the stability of the scale by calculating Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) where the ICC of 0.4 or above was considered acceptable [40].

All statistical analyses except confirmatory factor analysis were performed using the SPSS version 16.0 [41]. The confirmatory factory analysis was performed using the LISREL 8.80 for Windows [42].

Ethics

The ethics committee of Tarbiat Modares University approved the study. All patients gave their written informed consent.

Results

Participants

In all, 342 diabetic patients participated in this study. Of these, 204 patients took part in the main study and the remaining 138 patients completed the questionnaire in order to perform confirmatory factor analysis. The characteristics of the patients are shown in the Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin was 0.92, and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (5.55, P<0.001) showing sampling adequacy. The initial analysis indicated a 5-factor structure for the questionnaire with 3 items loading unexpectedly and irrelevant to the loaded construct. Thus, these were removed from the analysis and a final 30-item questionnaire loaded on five distinct constructs that jointly accounted for 72.3% of variance observed (Table 2) [Additional files 1 and 2].

Confirmatory factor analysis

The 30-item questionnaire was subjected to the confirmatory factor analysis. The relative chi-square (χ 2/df) was 2.03 indicating the fitness of the model (P<0.0001). All comparative indices of the model including CFI, IFI, NFI and NNFI were more than 0.9 (0.96, 0.96, 0.93 and 0.96 respectively) showing the goodness of fit for the data. The RMSEA of the model was 0.087 (90% CI=0.078-0.096). The SRMR was less than 0.08 (0.06) confirming an adequate fit for the model. The results obtained from the CFA are presented in Figure 1.

Reliability

The instrument had an excellent internal consistency (0.94). The intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.87 indicating an appropriate stability of the questionnaire. The results are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The present study reported the stages of designing and developing a scale for evaluating social support for self-care in middle-aged patients with type II diabetes and the findings indicated satisfactory psychometric properties for the questionnaire. Social support for self-care is a crucial issue in adults with diabetes [18]. It can contribute to treatment adherence and the outcomes. For instance, evidence suggests that encouraging families to exercise with their diabetic patients could increase physical activity among these people [17].

There are a number of scales for measuring social support [43–46] but to the authors’ best knowledge, there are only two questionnaires for assessing social support in diabetic patients the Diabetes Social Support Questionnaire, and the Diabetes Care Profile (DCP) [47–49]. The DSSQ is a well-known instrument and has been used in a number of studies on social support for self-care in diabetic patients [47, 50]. It was primarily developed for type I diabetic patients and measures insulin injection, blood glucose testing, meal plan, exercise and emotional support. The Diabetes Care Profile (DCP) is a set of different sections and one section including six questions related to social support. The DCP asks the support that one receives for meal plan, medicine, foot care, physical activity, testing blood sugar and emotional item [48]. However, the focus of current study was to develop a scale containing the five most important diabetes related behaviors namely nutrition, physical activity, self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), foot care and smoking. It is argued that when addressing self-care activities in diabetic patients, it is important to address the unmet needs for social support [49]. As different aspects of social support for self-care in diabetes patients might be considered, it is recommended that when assessing social support, there is need to decide which aspects of support are relevant to measure in any specific situation [51]. In this study, we thought diabetic patients need instrumental, informational and emotional support for self-care and thus, we considered these three aspects of social support and incorporated them to the all dimensions of the questionnaire as needed.

Performing both exploratory and factor analyses, the results indicated a good structure for this new instrument. Exploratory factor analysis indicated that the five-factor structure of the questionnaire could jointly account for 72.3% of the total observed variance. It seems that a careful selection of items related to social support for self-care might be the reason why we obtained such satisfactory results [52]. CFA also showed that factor structure of this scale was appropriate.

A reliable instrument can increase the power of the study to recognize real significant correlations and differences in the study [53]. Internal consistency of the final scale as measured by the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was found to be 0.94 indicating a desirable reliability. In addition, ICC showed appropriate stability for the scale as it was examined by 15 patients with a 2-weeks interval (0.87).

The main feature of the S4-MAD was the fact that it was developed for middle age diabetic patients (the main affected age group), and contained items on foot care and smoking. However, we did not include items on medications since neither patients nor experts did address the topic during the course of scale development. In addition a unique item (item 18) was included in this new instrument on reminding patients for blood glucose test every three months. The other characteristic of our questionnaire was related to its wording structure. Unlike other questionnaires that contain short statements for each item we used prolonged and complete sentences in order to help patients to understand the items and avoid confusion. Finally, we believe without losing any important dimension on social support for self-care, the S4-MAD is relatively a short questionnaire and easy to use.

This study however had few limitations. For example we did not perform concurrent validity in order to demonstrate the instrument correlates well with a measure that has previously been validated in Iran. Yet, the study had a number of strengths. Notably we recruited two separate samples for the study. In fact, as recommended, we used one sample for the EFA and another sample for the CFA.

Conclusion

The social support scale for self-care in middle-aged patients with type II diabetes is a valid and reliable instrument for evaluating the social support in these patients and now can be used in future studies of social support in patients with type II diabetes.

References

Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H: Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 & projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27: 1047-1053. 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047.

Friedman N, Bressler P: Advances in diabetes for the millennium: healthcare systems and diabetes mellitus. Med Gen Med. 2004, 6 (suppl 3): 1-

Foundation RWJ: The diabetes initiative: a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2006, New York: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Takizawa H, Hoshi T: A comparison of diabetes self-care ability scores among inhabitants of urban and rural areas and a group of company employees. Int J Urban Sci. 2010, 14: 86-97. 10.1080/12265934.2010.9693666.

van Dam HA, van der Horst FG, Knoops L, Ryckman RM, Crebolder HF, van den Borne BH: Social support in diabetes: a systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2005, 9: 1-12.

Lawn SH, Schoo A: Supporting self-management of chronic health conditions: common approaches. Patient Educ Couns. 2010, 80: 205-211. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.006.

Mc Dowell J, Courtney M, Edwards H, Shortridge Baggett L: Validation of the australian/english version of the diabetes management self-efficacy scale. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005, 11: 177-184. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00518.x.

Rosland AM, Kieffer E, Israel B, Cofield M, Palmisano G, Sinco B, Spencer M, Heisler M: When is social support important? The association of family support and professional support with specific diabetes self-management behaviors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008, 23: 1992-1999. 10.1007/s11606-008-0814-7.

McEwen MM, Pasvogel A, Gallegos G, Barrera L: Type 2 diabetes self-management social support intervention in the US-Mexico Border. Public Health Nurs. 2010, 27: 310-319. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00860.x.

Sarafino EP: Health Psychology: biopsychosocial interactions. 2005, New York: Wiley, 5

Drenta P, Clay OJ, Roth DL, Mittelman MS: Predictors of improvement in social support: five years effects of a structured intervention for caregivers of spouses with Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 63: 957-967. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.020.

Hogan BE, Linden W, Najarian B: Social support interventions: do they work?. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002, 22: 383-442.

Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K: Health Behavior and Health Education: theory, research, and practice. 2008, San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass, 3

Dennis CL: Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003, 40: 321-332. 10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00092-5.

Rees CA, Karter AJ, Young BA: Race/ethnicity, social support, and associations with diabetes self-care and clinical outcomes in NHANES. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36: 435-445. 10.1177/0145721710364419.

Okura T, Heisler M, Langa KM: The Association of cognitive function and social support with glycemic control in adults with diabetes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009, 57: 1816-1824. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02431.x.

Morris DB: A rural diabetes support group. Diabetes Educ. 1998, 24: 493-497. 10.1177/014572179802400408.

Bai YL, Chiou CP, Chang YY: Self-care behavior and related factors in older people with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2009, 18: 3308-3315. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02992.x.

Cheng ST, Chan ACM: The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: dimensionality and age and gender differences in adolescents. Pers Indiv Differ. 2004, 37: 1359-1369. 10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.006.

Colkesen EB, Niessen MA, Peek N, Vosbergen S, Kraaijenhagen RA, van Kalken CK, Tijssen JG, Peters RJ: Initiation of health-behavior change among employees participating in a web-based health risk assessment with tailored feedback. J Occup Med Toxico. 2011, 6: 5-10.1186/1745-6673-6-5.

Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, Dijkstra A: Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Educ Res. 2008, 23: 454-466. 10.1093/her/cyn004.

Friedman MS: The Handbook of Health Psychology. 2011, New York: Oxford University Press

Elo S, Kyngäs H: The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008, 62: 107-115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG: Naturalistic Inquiry. 1985, Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications

Fitzner K: Reliability and validity: a quick review. Diabetes Educ. 2007, 33: 775-780. 10.1177/0145721707308172.

Wynd CA, Schmidt B, Atkins Schaefer M: Two quantitative approaches for estimating content validity. Western J Nurs Res. 2003, 25: 508-518. 10.1177/0193945903252998.

Hajizadeh E, Asghari M: Statistical Methods and Analyses in Health and Biosciences: A Methodological Approach. 2011, Tehran: ACECR Press, [Persian], 1

Lawshe CH: The quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psycho. 1975, 28: 563-575. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x.

Waltz C, Bausell RB: Nursing Research: design, statistics and computer analysis. 1983, Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co

Polit DF, Beck CT: The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006, 29: 489-497. 10.1002/nur.20147.

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH: Psychometric Theory. 1994, New York: Mc Graw-Hill Inc, 3

Mueller RO: Basic principles of structural equation modeling: an introduction to LISREL and EQS. 1996, New York: Springer

Munro BH: Statistical methods for health care research. 2005, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Co, 5

Kline RB: Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2010, New York: Guilford Press, 3

MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM: Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. 1996, 1: 130-149.

Bollen KA, Long JS: Testing structural equation models. 1993, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Hu L, Bentler PM: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Model. 1999, 6: 1-55. 10.1080/10705519909540118.

Schneider Z: Nursing research: an interactive learning. 2004, London: Mosby Co., 1

Litwin MS: How to Measure Survey Reliability and Validity. 1995, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Baumgartner TA, Chung H: Confidence limits for intra class reliability coefficients. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2001, 5: 179-188. 10.1207/S15327841MPEE0503_4.

SPSS Inc: SPSS 16.0 for Windows. 2008, SPSS Inc, Chicago

Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D: LISREL 8.80 for Windows. 2006, Lincolnwood, IL; Scientific Software International, Inc

Social support questionnaire. http://www.innateliving.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/social-support-questionnaire.pdf,

Norbeck social support questionnaire (NSSQ). http://nurseweb.ucsf.edu,

Sources of social support scale (SSSS). http://www.psy.miami.edu/faculty/ccarver/sclSSSS.html,

Malecki CK, Demary MK: Measuring perceived social support: development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS). Psychol Sch. 2002, 39: 1-18. 10.1002/pits.10004.

La Greca AM, Bearman KJ: The diabetes social support questionnaire- family version: evaluating adolescents’ diabetes- specific support from family members. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002, 27: 665-676. 10.1093/jpepsy/27.8.665.

Diabetes care profile. http://www.med.umich.edu/mdrtc/profs/documents/svi/dcp.pdf,

Song Y, Song HJ, Han HR, Park SY, Nam S, Kim MT: Unmet needs for social support and effects on diabetes self-care activities in Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2012, 38: 77-85. 10.1177/0145721711432456.

Bearman KJ, La Greca AM: Assessing friend support of adolescents’ diabetes care: the diabetes social support questionnaire- Friends version. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002, 27: 417-428. 10.1093/jpepsy/27.5.417.

Fisher EB, Boothroyd RI, Coufal MM, Baumann LC, Mbanya JC, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Sanguanprasit B, Tanasugarn C: Peer support for self-management of diabetes improved outcomes in international settings. Health Aff. 2012, 31: 130-139. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0914.

Burns N, Grove SK: The practice of nursing research: conduct, critique & utilization. 2005, Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 5

DeVellis RF: Scale development: Theory and Applications. 2003, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/1035/prepub

Acknowledgement

This article is a part of a PhD thesis. The authors are thankful for help and support received from Tarbiat Modares University and the Health Education and Promotion Office of Ministry of Health and Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS). We also appreciate all patients who participated in this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SHNM was the main investigator, collected the data, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. SHN supervised the project and contributed to all aspects of the study. FA, and EH were the study consultants. AM helped as a consultant and contributed to the study design, analysis, provided the final draft, and revised the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12889_2012_4653_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: The S4-MAD. The file contains the Social Support Scale for Self-Care in Middle-Aged Patients with Type II Diabetes. (DOC 299 KB)

12889_2012_4653_MOESM2_ESM.doc

Additional file 2: Scoring Instruction. The file contains the scoring instruction for the Social Support Scale for Self-Care in Middle-Aged Patients with Type II Diabetes. (DOC 20 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Naderimagham, S., Niknami, S., Abolhassani, F. et al. Development and psychometric properties of a new social support scale for self-care in middle-aged patients with type II diabetes (S4-MAD). BMC Public Health 12, 1035 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1035

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1035