Abstract

Background

Psychiatric patients have more physical health problems and much shorter life expectancies compared to the general population, due primarily to premature cardiovascular disease. A multi-causal model which includes a higher prevalence of risk factors has provided a valid explanation. It takes into consideration not only risks such as gender, age, and family history that are inherently non-modifiable, but also those such as obesity, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia that are modifiable through behavioural changes and improved care. Thus, it is crucial to focus on factors that increase cardiovascular risk. Obesity in particular has been associated with both the lifestyle habits and the side effects of antipsychotic medications. The present systematic review and meta-analysis aims at collecting and updating available evidence on the efficacy of non-pharmacological health promotion programmes for psychotic patients in randomised clinical trials.

Methods

We systematically reviewed the randomised controlled trials from 1990 onward, in which psychoeducational and/or cognitive-behavioural interventions aimed at weight loss or prevention of weight gain in patients with psychosis had been compared to treatment as usual. We carried out a meta-analysis and pooled the results of the studies with Body Mass Index as primary outcome.

Results

The results of the meta-analysis show an effect toward the experimental group. At the end of the intervention phase there is a −0.98 kg/m2 reduction in the mean Body Mass Index of psychotic subjects. Notably, prevention studies with individual psychoeducational programmes that include diet and/or physical activity seem to have the highest impact.

Conclusions

When compared with treatment as usual in psychotic patients, preventive and individual lifestyle interventions that include diet and physical activity generally prove to be effective in reducing weight. Physical screening and monitoring programmes are well accepted by patients and can be implemented in a variety of settings. A weight loss of 0.98 points in the Body Mass Index corresponds to a loss of 3.12% of the initial weight. This percentage is below the 5% to 10% weight loss deemed sufficient to improve weight-related complications such as hypertension, type II diabetes, and dyslipidemia. However, it is reported that outcomes associated with metabolic risk factors may have greater health implications than weight changes alone. Therefore, in addition to weight reduction, the assessment of metabolic parameters to monitor other independent risk factors should also be integrated into physical health promotion and management in people with mental disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In comparison to the general population, psychiatric patients, especially those with severe mental illness (SMI) such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, have worse physical health and a much shorter life expectancy, due primarily to premature cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1]. This finding has been explained with a multi-causal model including a higher prevalence of risk factors, namely, high blood pressure, high plasma cholesterol, obesity, smoking, diabetes, self-neglect tendencies, unhealthy lifestyles, medication side-effects, and low socio-economic status [2]. Risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality include those that are inherently non-modifiable (gender, age, family history) and those that are modifiable through behavioural changes and improved care (obesity, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) [3]. Sedentary lifestyles and limited access to low-calorie, high-nutrient foods are but two examples of potential modifiable contributors to obesity in these patients [4].

In order to improve the long-term health of patients with schizophrenia, given their increased risk of CVD, it is imperative to focus attention on factors, such as obesity, which further increase this risk [5]. Among individuals with schizophrenia and affective disorders, obesity is 1.5-2 times higher than in the general population [6]. It has been associated not only with lifestyle habits but also with the side effects of antipsychotic medications, posing serious problems for physical and mental health, including a higher mortality [7]. It has been demonstrated that atypical antipsychotics (in particular, olanzapine and clozapine) contribute to weight gain, albeit with different weight gain liabilities (ziprasidone, for example, has the least) [8, 9].

Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses exist on this topic, one [10] on non-pharmacological interventions for antipsychotic-induced weight gain and the other [11] on both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. The first review [10] addresses non-pharmacological interventions for antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and it identifies 10 studies [12–21]. According to the authors, adjunctive non-pharmacological interventions are effective in reducing or attenuating antipsychotic-induced weight gain when compared with treatment as usual in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, and treatment effects may be maintained through follow-ups [10]. The second review [11] focuses on both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for weight reduction in schizophrenic patients or patients with SMI. Evidence from 5 studies on non-pharmacological treatments [12–14, 16, 19] has been gathered and updated to 2010. In this population, according to the authors, non-pharmacological interventions are possible and show acceptable compliance, although conclusions regarding the intensity of the intervention cannot be made at this stage, and thus there is the need for further randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with long-term follow-ups [11]. However, the role of physical inactivity and poor diet as independent risk factors for CVD infers the need for non-pharmacological, lifestyle interventions regardless of weight loss per se. According to the authors, there is also insufficient evidence to support the general use of pharmacological interventions for weight management in people with schizophrenia [11].

Our systematic review and meta-analysis aims at collecting and updating available evidence on the efficacy of non-pharmacological health promotion programmes for psychotic patients in randomised clinical trials, extending the search period beyond the years covered by the other reviews. The twofold objective is to provide evidence about the physical health of psychiatric patients regarding excessive weight gain, in order to increase awareness of this issue in both the scientific community and the relevant stakeholders, and to expand the setting up of effective intervention programmes. The main outcome variable taken into consideration is Body Mass Index (BMI), as specified and explained in Methods.

Methods

We reviewed RCTs from 1990 onward, which pertain to psychoeducational and/or cognitive-behavioural interventions aimed at weight loss or prevention of weight gain in patients with psychosis. The present work is part of a larger systematic review (to be published) which, after a wide-scale search of the literature on physical health promotion interventions in psychiatric patients, considers not only weight management interventions but also interventions targeted at smoking, diet, physical activity, and HIV prevention.

Eligibility criteria

We considered as eligible those randomised clinical trials on the efficacy of weight management interventions which had been published in English from 1990 up to the date of the search. They included at least 50% of adult subjects between the ages of 18 and 65 who, according to the International Classification of Disorders (ICD) [22] (codes F20-25, F28-31, F32.3, F33.3), had been diagnosed with: schizophrenia and related disorders (schyzotypal disorder, delusional disorder, acute and transient psychotic disorders, induced psychotic disorder, schizoaffective disorder, other nonorganic psychotic disorders, unspecified nonorganic psychosis), bipolar affective disorder, manic episode, depressive episode with psychotic symptoms or depressive disorder with psychotic symptoms. We included in our review those studies based on programmes aimed at weight reduction or prevention of weight gain through cognitive-behavioural, psychoeducational, nutritional or physical activity-based interventions. We excluded pharmacological interventions used to reduce weight.

The primary outcome considered is mean BMI (kg/m2) of the groups at endpoint or change in BMI. Although the use of BMI has limitations, because it does not distinguish between fat and lean mass nor does it adjust for age or sex, it is generally accepted as a reasonable guide for clinical and epidemiologic purposes [23].

Search strategy

Only relevant studies from 1990 onward were considered, since previously published reviews had already covered the years prior to that date [10, 11]. The following search terms were used: psychosis and intervention and health promotion or health education or physical health or smoking or weight gain or exercise or HIV risk or AIDS or infection. The searches were made on: a) Pubmed, Web of Science, PsycInfo, Embase databases, b) the Cochrane Library, c) reference section of retrieved papers and review articles. The last search, performed in May 2010, was later updated to cover the period up to and including December 2011. To satisfy the specific aims of this review, only studies relevant to weight gain were selected from the results.

Study selection

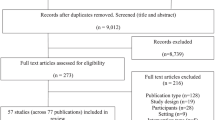

Records retrieved from the search were screened by title. Possible inclusions were screened by abstract. Full text and relevant papers were then selected. Conference abstracts and letters to the editor were excluded. For the meta-analysis, we considered eligible RCTs on weight management interventions. It was decided to contact the authors of the studies that did not include sufficient data for statistical analysis. Two reviewers discussed dubious cases in order to reach an agreement on the inclusion of studies.

Data extraction

Relevant data for the systematic review and for the meta-analysis were extracted by 2 of our authors using the format: 1) inclusion criteria; 2) characteristics of the sample (diagnosis of the subjects, duration of the illness, i.e., first episode or chronic psychosis); 3) number of subjects that entered the analysis in the experimental and in the control group; 4) number of drop-outs; 5) type of intervention (prevention of weight gain or weight loss, group or individual, cognitive-behavioural or psychoeducational, diet and/or physical activity); 6) mean and standard deviation (SD) of the outcome considered (BMI or BMI change) in both the experimental and the control group at baseline and endpoint. We assessed the risk of bias based on the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [24].

The summary measure considered is the mean difference (MD) of the primary outcome (BMI or BMI change) in the experimental and the control group at baseline and endpoint. The statistical method used for the meta-analysis is inverse variance, with a random-effects approach, utilising RevMan (Cochrane Collaboration’s software for meta-analyses). Heterogeneity is investigated by the I2 statistic [25].

We hypothesized that the methodological quality of the studies and some characteristics of the samples and procedures used might influence the variability of results. As a means of investigating the heterogeneity of results and answering specific questions about particular patient groups and types of interventions, we decided to carry out subgroup analyses, making the following comparisons:

first episode psychosis vs. chronic psychosis;

weight gain prevention vs. weight loss;

group intervention vs. individual intervention;

use of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) vs. psychoeducation;

physical activity vs. no physical activity;

diet vs. no diet.

We also decided to analyse the differences between experimental and control groups regarding the number of drop-outs. We determined to assess the robustness of the findings through sensitivity analyses.

Results

Seventeen RCTs were retrieved from the search. Five did not provide sufficient information for meta-analysis [18, 26–29]. However, only 4 studies were excluded [18, 27–29] because in one case [26] the authors supplied the missing data. For one study we had to impute SDs from the pool of data [30]. Therefore, 13 RCTs were eligible for inclusion [12–17, 19–21, 26, 30–32]. More details on the screening process can be found in Figure 1.

Five studies included CBT interventions whereas 8 included psychoeducational or other types of intervention. Four studies evaluated an individual intervention and 9 evaluated a group intervention. Four studies included some physical activity and 3 included a diet. In all the studies except one [31], the control group was given treatment as usual and in some cases, brief nutritional information [14–17, 20].

Interventions lasted between 2 and 12 months. The mean duration of interventions (excluding the one of Brown and Smith [26] who did not provide information) is about 18 weeks. Three studies reported follow-up periods of 2 to 3 months [12, 14, 20]. The trials were carried out in Europe, United States of America (USA), Asia and Australia.

More detailed information on the characteristics of the studies is reported in Table 1 and in the paragraph “Heterogeneity of studies”.

Risk of bias

The assessment of risk of bias is presented in Figure 2 and Additional file 1: Table S1. Only few studies describe random sequence generation [15, 26, 31] while none describes allocation concealment. None of the trials has a double-blind design. Three of them are single-blind trials [15, 19, 26], however in one of the studies it is stated that blinding of assessors was occasionally difficult to achieve [15]. Mauri et al. [32] and Khazaal et al. [20] have an open-label design. The remaining studies do not report information on blinding. Four studies report only data for completers [14, 17, 19, 21] and thus do not address incomplete data adequately. Seven studies included all the subjects in the analyses or provided intention-to-treat analysis [12, 13, 15, 16, 26, 30, 32]. It should be noted that poor quality randomisation can produce unequal groups at baseline: Such might be the case of some studies in this review [20, 26]. In Weber & Wyne [19] subjects were given $5 for each complete visit.

Results for all interventions

The main analysis (Figure 3) shows an effect toward the experimental groups, with a reduction in mean BMI of −0.98 kg/m2, compared to the control groups (95% CI: -1.31 kg/m2 to −0.65 kg/m2). A statistical test for heterogeneity failed to suggest substantial heterogeneity.

Drop-outs

There are no significant differences in the number of drop-outs between experimental and control groups (OR = 1.08 95% CI 0.67 to 1.73), except for Evans et al. [14], which has a greater number of drop-outs in the control group. In that trial, 6 of the 11 drop-outs in the control group are due to discontinuation or non-adherence regarding olanzapine treatment (introduced at the beginning of treatment) and 5 are due to non-contactable issues.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses (Table 2) demonstrate that studies about weight gain prevention with individual psychoeducational programmes that include diet and/or physical activity seem to have the highest impact. However, it is also true that a greater sample size relates to a greater heterogeneity and smaller effect size, except for the comparison between CBT and psychoeducation, where the contrary is true. Concerning the length of illness, both studies with chronic patients and first-episode patients seem to have similar effects. The study with mixed sample seems to be more successful in the reduction of weight.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the findings with respect to: a) the choice of fixed-effect or random-effects methods, b) the exclusion of studies that provided only BMI values instead of BMI changes, c) the exclusion of trials with a duration of less than 12 weeks or more than 1 year, d) the exclusion of trials with control groups that are not completely inactive.

Heterogeneity of studies

Even though our analysis did not detect statistically significant heterogeneity, study samples are heterogeneous according to mean initial weight, length of illness, diagnosis, and pharmacological therapy. In 5 of the 13 studies, both the experimental and the control group at baseline have a mean BMI in the obesity category (30–39.9 kg/m2) [17, 19, 21, 26, 32]. In 3 studies the mean BMI of the experimental and control subjects falls into the overweight category (25–29.9 kg/m2) [12, 14, 16]. One study included subjects with a mean BMI in the normal category [15]. In Milano et al. [30], Forsberg et al. [31] and Khazaal et al. [20], the control group falls into a lower category of BMI when compared to the experimental group. In the remaining study mean BMI at baseline is not known [13], but one of the inclusion criteria is BMI > 26. Such differences in weight at the beginning of intervention may have a role in influencing the total intervention effect. It is important to note that most studies on weight gain prevention included normal weight or overweight subjects whereas studies on weight loss included obese or overweight subjects. We included only those studies with at least 50% psychotic patients, although most authors include other diagnoses in their studies. However, all patients take antipsychotics. In one of the studies the sample consisted of drug-naïve first-episode patients [17]. The length of illness varies (from first-episode patients to chronic patients) with a maximum length of about 26 years. The mean age is also variable. At times in the same study, some patients take typical antipsychotics while others take atypical antipsychotics that may be for specific study purposes only [12, 14, 15, 30]. Some authors do not specify the type of antipsychotic therapy used in their study [17, 19, 27, 29].

Trials are also heterogeneous according to objectives (weight gain prevention or weight loss), type and duration of interventions (presence or absence of diet and/or physical activity, psychoeducation or CBT, duration, follow-up etc.), background/training of professionals, control group (treatment as usual, informative booklets or sessions, treatment not specified), and methodological sophistication. It must be stated that it is very difficult to properly perform RCTs in this field due to the amount of external confounding influences [33]. A number of studies lack a description of the randomisation procedure. For further information on randomisation and methodological characteristics of the studies refer to Additional file 1: Table S1.

Discussion

The results of the meta-analysis show that when compared to treatment as usual, preventive and individual lifestyle interventions including diet and physical activity generally reduce weight in psychotic patients by −0.98 BMI points. Such weight loss corresponds to a loss of 3.12% of the initial weight (31.36 kg/m2, except [13], for which we do not have baseline BMI data). However, a weight loss of 5% to 10% is the criterion for success proposed by the National Institute of Health/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the World Health Organization, and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Nonetheless, even though a 3.12% loss is below percentages reported as sufficient to improve weight-related complications including hypertension, type II diabetes, and dyslipidemia [34–36], Gabriele et al. [37] state that in individuals taking atypical antipsychotics, outcomes associated with metabolic risk factors may have greater health implications than weight changes alone. Therefore, in addition to weight measurements, the assessment of metabolic parameters should also constitute integral part of physical health monitoring in people with mental disorders, because it can provide meaningful information on weight-related health status.

Poor results of weight management interventions can be due to their short duration or to their lack of follow-up sessions. The mean duration of interventions in the trials included is only about 18 weeks with a median of 12 weeks. The lack of follow-up is evidenced by the fact that out of the 13 trials, only 3 provided follow-up sessions, one after 2 and the other two after 3 months [12, 14, 20]. Álvarez Jiménez et al. [15] and McKibbin et al. [17] did expand their studies with a 2-year and a 6-month follow-up respectively [38, 39]. It is significant that in the general population, obese patients treated with behaviour therapy for 20 to 30 weeks typically regain about 30% to 35% of their lost weight in the year following treatment [40]. Although studies do not yet provide clear evidence as to the optimum length of engagement in these programmes, experience in the general population suggests that lifestyle change needs to be permanent [41]. Thus, intervention programmes should last at least 20 weeks and should provide follow-ups consisting of booster sessions for behavioural control and for diet and physical activity control. In any case, attention should be brought to the fact that an 18 week follow-up is a very short period of time compared to the estimated 25 years of life which are lost in these patients due to metabolic syndrome [42].

Strengths of the study

Scientific research in this field is relatively new. Differences between countries regarding resources, physical and mental health services, and attitudes toward physical and mental illness can be expected to produce wide variations in physical health care for patients with SMI [43]. This review contributes to the update of available evidence and it highlights the fact that in recent years, interest of both researchers and clinicians toward the physical health of mental patients has increased. Thus, we are witnessing a rise in the number of studies on physical comorbidity in this population. Most of the studies are conducted in outpatient settings located in Europe or USA, except for the one inpatient setting located in Asia. More and more mental patients are treated in the community, where they may receive less physical health attention than hospitalised patients, and precisely for this reason it is important to focus on the health status of outpatients. It is also important to point out that the homogeneity in the setting of the studies is useful for testing feasibility of interventions in routine contexts. Health promotion interventions seem to meet the current requirements of psychiatric services, which prove to be the right setting for physical health care in this particular population. According to Chaudhry and colleagues [44], the physical health of hospitalised patients is closely monitored (although some simple and relevant indexes, e.g., waist circumference, are usually not recorded routinely). However, in the case of adverse effects, switching antipsychotic therapy is more likely to be considered for neurological side effects rather than for abnormal lab findings such as those of the metabolic syndrome. Dangers arising from metabolic disturbances are not yet fully appreciated. Patients in the community are an urgent priority for improved monitoring and long-term management [44]. This seems feasible. In fact, we found a lack of statistically significant differences in the number of drop-outs between experimental and control groups, which suggests that dropping-out depends on factors not related to the feasibility and acceptability of the interventions per se. Physical screening and monitoring programmes may be well accepted by patients and can be implemented in a variety of settings.

Limitations

Limitations at study level

A notable limitation at study level regards heterogeneity, which has been presented in Results (“Heterogeneity of studies”).

Limitations at review level

We conducted a methodical search of literature to find every relevant trial for our research question. However, we do not exclude the possibility of reporting bias.

It must also be taken into account that the following factors may have influenced the results of the meta-analysis:

-

few studies describe the randomisation method;

-

no study describes allocation concealment;

-

few studies describe blinding;

-

some studies only report data for completers or do not report the reasons for missing data;

-

in one study subjects received money for their participation ( Additional file 1: Table S1).

With respect to informativeness, 4 studies out of 17 did not include data essential to carry out a meta-analysis, therefore we were forced to exclude them from our review. Other papers lack information on reasons for missing data and do not use approaches to deal with missing outcome data, such as intention-to-treat analysis or “last observation carried forward”. This may be a problem because missing outcome data, due to attrition (drop-out) during the study or exclusions from the analysis, raise the possibility of a bias in the observed effect estimate [24].

Implications for future research

As to research methodology, more comparable and more rigorous research methods would be advantageous. This would facilitate the comparisons and the testing of possible confounding factors and methodological biases on the outcome of interventions, and subsequently on the result of meta-analyses. Greater sample sizes and more studies would be necessary. More information on the cost-effectiveness of interventions would also be of use. Information on missing data in trials would need to be provided as it is crucial for the understanding of their influence on outcome, efficacy, and effectiveness of proposed interventions.

As to intervention methodology, it is important for professionals to have a more homogeneous background or at least a psychiatric professional background. Besides weight measurement, the measurement of both obesity-related physical health parameters (such as waist circumference) and metabolic parameters, should be considered mandatory in future protocols. The individual components of the metabolic syndrome, as well as some other non-metabolic parameters, should be checked at baseline and measured regularly thereafter (especially in drug- naïve first-episode patients, children and adolescents) [45]. In the present review some, but not all trials included such secondary outcomes.

Conclusions

The studies reviewed are still to be considered preliminary. Our hope is that this paper will be a small but inspiring step toward the development of larger and much longer studies. Although the findings of this paper are to be regarded as of a preliminary nature, it is hoped that they will be instrumental in bringing this problem to the attention of medical practitioners world-wide. It is clear that more research is required, especially with an increase in the number of parameters under study. However, it is also clear that patients with SMI are willing to participate and remain in health promotion programmes. Consequently, these programmes may have positive effects in diminishing risk factors, with relevant impact on clinical practice.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BT:

-

behavioural therapy

- CBT:

-

Cognitive-behavioural therapy

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- N/A:

-

Not available

- NOS:

-

Not otherwise specified

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- SMI:

-

Severe mental illness

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- UC:

-

usual care

- USA:

-

United States of America.

References

Fleischacker WW, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, De Hert M, Hennekens CH, Lambert M, Leucht S, Maj M, McIntyre M, Naber D, Newcomer JW, Olfson M, Osby U, Sartorius N, Lieberman JA: Comorbid somatic illnesses in patients with severe mental disorders: clinical, policy and research challenges. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008, 64 (4): 514-519.

De Hert M, Correll C, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Cohen D, Asai I, Detraux J, Gautam S, Möller H, Ndetei DM, Newcomer JW, Uwakwe R, Leucht S: Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011, 10: 52-77.

Heald A: Physical health in schizophrenia: a challenge for antipsychotic therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2010, 25 (Suppl 2): S6-S11.

Allison DB, Newcomer JW, Dunn AL, Blumenthal JA, Fabricatore AN, Daumit GL, Cope MB, Riley WT, Vreeland B, Hibbeln JR, Alpert JE: Obesity among those with mental disorders. A National Institute of Mental Health meeting report. Am J Prev Med. 2009, 36 (4): 341-350.

Van Gaal LF: Long-term health considerations in schizophrenia: metabolic effects and the role of abdominal adiposity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006, 16: S142-S148.

American Diabetes Association American Psychiatric Association American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists North American Association for the Study of Obesity: Consensus Development Conference on Antipsychotic Drugs and Obesity and Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27 (2): 596-601.

Loh C, Meyer JM, Leckband SG: A comprehensive review of behavioral interventions for weight management in schizophrenia. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006, 18 (1): 23-31.

Allison D, Mentore J, Heo M, Chandler L, Cappelleri J, Infante M, Weiden P: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999, 156: 1686-1696.

Samele C: Factors leading to poor physical health in people with psychosis. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2004, 13 (3): 141-5. 10.1017/S1121189X00003407.

Alvarez Jiménez M, Hetrick SE, González Blanch C, Gleeson JF, McGorry PD: Non-pharmacological management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2008, 193: 101-107. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.042853.

Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G: Interventions to reduce weight gain in schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, (Issue 1)

Littrell KH, Hilkligoss NM, Kirshner CD, Petty RG, Johnson CG: The effects of an educational intervention on antipsychotic-induced weight gain. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003, 35 (3): 237-241. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00237.x.

Brar JS, Ganguli R, Pandina G, Turkoz I, Berry S, Mahmoud R: Effects of behavioral therapy on weight loss in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005, 66 (2): 205-212. 10.4088/JCP.v66n0208.

Evans S, Newton R, Higgins S: Nutritional intervention to prevent weight gain in patients commenced on olanzapine: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005, 39: 479-486.

Alvarez Jiménez M, González Blanch C, Vázquez Barquero JL, Pérez Iglesias R, Martínez García O, Pérez Pardal T, Ramírez Bonilla ML, Crespo Facorro B: Attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain with early behavioral intervention in drug-naive first-episode psychosis patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006, 67 (8): 1253-1260. 10.4088/JCP.v67n0812.

Kwon JS, Choi JS, Bahk WM, Kim CY, Kim CH, Shin YC, Park BJ, Geun C: Weight management program for treatment emergent weight gain in olanzapine treated patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders: a 12-week randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006, 67 (4): 547-553. 10.4088/JCP.v67n0405.

McKibbin CL, Golshan S, Griver K, Kitchen K, Wykes TL: A healthy lifestyle intervention for middle-aged and older schizophrenia patients with diabetes mellitus: A 6-month follow-up analysis. Schizophr Res. 2006, 121: 203-206.

Scocco P, Longo R, Caon F: Weight change in treatment with olanzapine and a psychoeducational approach. Eat Behav. 2006, 7: 115-124. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.08.003.

Weber M, Wyne K: A cognitive/behavioral group intervention for weight loss in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2006, 83: 95-101. 10.1016/j.schres.2006.01.008.

Khazaal Y, Fresard E, Rabia S, Chatton A, Rothen S, Pomini V, Grasset F, Zullino D: Cognitive behavioural therapy for weight gain associated with antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Res. 2007, 91: 169-177. 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.025.

Wu MK, Wang CK, Bai YM, Huang CY, Lee SD: Outcomes of obese, clozapine-treated inpatients with schizophrenia placed on a six-month diet and physical activity program. Psychiatr Serv. 2007, 58 (4): 544-550. 10.1176/appi.ps.58.4.544.

World Health Organization: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. 2010, Geneva

Coodin S: Body mass index in persons with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2001, 46: 549-556.

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Edited by: Higgins JPT, Green S. 2011, The Cochrane Collaboration, [http://www.cochrane-handbook.org]

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003, 327: 557-560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Brown S, Smith E: Can a brief health promotion intervention delivered by mental health key workers improve clients’ physical health: a randomized controlled trial. J Ment Health. 2009, 18 (5): 372-378. 10.3109/09638230802522460.

Ganguli R, Brar JS: Prevention of weight gain, by behavioral interventions, in patients starting novel antipsychotics. Schizophr Bull. 2005, 31: 561-562.

Skrinar GS, Huxley NA, Hutchinson DS, Menninger E, Glew P: The role of a fitness intervention on people with serious psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2005, 29 (2): 122-127.

Jean-Baptiste M, Tek C, Liskow E, Rao Chakunta U, Nicholls S, Hassan AQ, Brownell KD, Wexler BE: A pilot study of a weight management program with food provision in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007, 96: 198-205. 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.022.

Milano W, Grillo F, Del Mastro A, De Rosa M, Sanseverino B, Petrella C: Appropriate intervention strategies for weight gain induced by olanzapine: a randomised controlled study. Adv Ther. 2007, 24 (1): 123-133. 10.1007/BF02850000.

Forsberg KA, Björkman T, Sandman PO, Sandlund M: Physical health - a cluster randomized controlled lifestyle intervention among persons with a psychiatric disability and their staff. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008, 62 (6): 486-495. 10.1080/08039480801985179.

Mauri M, Castrogiovanni S, Simoncini M, Iovieno N, Miniati M, Rossi A, Dell’Agnello G, Fagiolini A, Donda P, Cassano GB: Effects of an educational intervention on weight gain in patients treated with antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008, 26 (5): 462-466.

Veit T, Barnas C: Diet blues: methodological problems in comparing non-pharmacological weight management programs for patients with schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2009, 13 (3): 173-183. 10.1080/13651500902763840.

Wadden TA, Foster GD: Behavioral treatment of obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2000, 84 (2): 441-461. 10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70230-3.

Vetter ML, Faulconbridge LF, Webb VL, Wadden TA: Behavioral and pharmacologic therapies for obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010, 6 (10): 578-588.

Wu T, Gao X, Chen M, Van Dam RM: Long-term effectiveness of diet-plus-exercise interventions vs. diet-only interventions for weight loss: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2009, 10: 313-323. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00547.x.

Gabriele JM, Dubbert PM, Reeves RR: Efficacy of behavioural interventions in managing atypical antipsychotic weight gain. Obes Rev. 2009, 10: 442-455. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00570.x.

Alvarez Jiménez M, Martínez García O, Pérez Iglesias R, Ramírez ML, Vázquez Berquero JL, Crespo Facorro B: Prevention of antipsychotic-induced weight gain with early behavioural intervention in first-episode psychosis: 2-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2010, 116: 16-19. 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.012.

McKibbin CL, Golshan S, Griver K, Kitchen K, Wykes TL: A healthy lifestyle intervention for middle-aged and older schizophrenia patients with diabetes mellitus: a 6-month follow-up analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010, 121: 203-206. 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.039.

Wadden TA, Crerand CE, Brock J: Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005, 28: 151-170. 10.1016/j.psc.2004.09.008.

Bushe C, Haddad P, Peveler R, Pendlebury J: The role of lifestyle interventions and weight management in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2005, 19 (6): Supplement:28-35.

Colton CW, Manderscheid RW: Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006, 3 (2): 1-14.

Montejo AL: The need for routine physical health care in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2010, 25 (Suppl 2): S3-S5.

Chaudhry IB, Jordan J, Cousin FR, Cavallaro R, Mostaza JM: Management of physical health in patients with schizophrenia: international insights. Eur Psychiatry. 2010, 25 (Suppl 2): S37-S40.

De Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Leucht S, Ndetei DM, Newcomer JW, Uwakwe R, Asai I, Möller H, Gautam S, Detraux J, Correll C: Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry. 2011, 10 (2): 138-151.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/12/78/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge professor Corrado Barbui, University of Verona, for his valuable supervision and advice on the meta-analysis, and John Vanzini for his accurate revision of the English language.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CG carried out the review. FM updated it. CG, LBe, FM, and EB implemented data extraction. EB performed the meta-analysis and drafted the manuscript. LBu conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and participated in the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Elena Bonfioli, Loretta Berti, Claudia Goss, Francesca Muraro and Lorenzo Burti contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonfioli, E., Berti, L., Goss, C. et al. Health promotion lifestyle interventions for weight management in psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry 12, 78 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-78

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-78