Abstract

Background

Cocaine, particularly in its base form ('crack'), has become one of the drugs of most concern in the Netherlands, being associated with a wide range of medical, psychiatric and social problems for the individual, and with significant public order consequences for society. Available treatment options for cocaine dependent users are limited, and a substantial part of the cocaine dependent population is not reached by the addiction treatment system. Psychosocial interventions for cocaine dependence generally show modest results, and there are no registered pharmacological treatments to date, despite the wide range of medications tested for this type of dependence.

The present study (Cocaine Addiction Treatments to improve Control and reduce Harm; CATCH) investigates the possibilities and problems associated with new pharmacological treatments for crack dependent patients.

Methods/Design

The CATCH-study consists of three separate randomised controlled, open-label, parallel-group feasibility trials, conducted at three separate addiction treatment institutes in the Netherlands. Patients are either new referrals or patients already in treatment. A total of 216 eligible outpatients are randomised using pre-randomisation double-consent design and receive either 12 weeks treatment with oral topiramate (n = 36; Brijder Addiction Treatment, The Hague), oral modafinil (n = 36; Arkin, Amsterdam), or oral dexamphetamine sustained-release (n = 36; Bouman GGZ, Rotterdam) as an add-on to cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), or receive a 12-week CBT only (controls: n = 3 × 36).

Primary outcome in these feasibility trials is retention in the underlying psychosocial treatment (CBT). Secondary outcomes are acceptance and compliance with the study medication, safety, changes in cocaine (and other drug) use, physical and mental health, social functioning, and patient satisfaction.

Discussion

To date, the CATCH-study is the first study in the Netherlands that explores new treatment options for crack-cocaine dependence focusing on both abstinence and harm minimisation. It is expected that the study will contribute to the development of new treatments for one of the most problematic substance use disorders.

Trial Registration

The Netherlands National Trial Register NTR2576

The European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials EudraCT2009-010584-16

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cocaine, particularly in its base form ('crack'), has become one of the drugs of most concern in many countries, being associated with a wide range of medical, psychiatric and social problems for the individual, and with significant public order consequences for society [1–3]. In the Netherlands (16.7 million inhabitants), annual cocaine-related addiction treatment demand increased from 8,490 patients in 1994 to 17,270 in 2008, and approximately half of this treatment demand in 2008 concerned users of crack [4]. Although the number of treatment seeking cocaine users slightly decreased in more recent years, the number of cocaine dependent patients that repeatedly returned to addiction treatment increased [5]. Despite its status as one of the most problematic addictions, reliable prevalence estimates of cocaine dependence in the Netherlands are lacking. In 2005, 32,000 current cocaine users were identified in the Netherlands [4], but this is likely to be a serious underestimation given the fact that the data were obtained in a population survey. Moreover, the survey did not allow a separate estimate of the prevalence of crack cocaine use.

Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence, which include cognitive behavioural therapy, counselling and relapse prevention, have generally produced modest results [6, 7], and both study data and practice-based experiences indicate that poor compliance is a major complicating factor in these treatments. One of the more promising psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence to date is contingency management, which has shown positive results in terms of improved treatment retention and reduction of substance use in a series of studies [7–11], and is therefore currently being investigated in the Netherlands in the context of a controlled study in heroin addicts with concurrent cocaine use. However, dissemination of contingency management has been problematic because of low acceptance and limited experience of therapists with this intervention [12] and because contingency management is politically controversial because communities are often not willing to just pay for a change in health behaviour [13].

The modest results of psychosocial treatments and the increasing knowledge about the neurobiology of cocaine dependence have led to an increasing number of studies searching for effective pharmacological agents that influence the neurochemistry of cocaine, including antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, psychostimulants and (other) dopamine agonists [14–22]. Despite the considerable efforts in this field, however, there are no proven effective pharmacotherapies for cocaine dependence to date, and the testing of new medications for cocaine dependence should continue to be high on the research agenda. Basically, the research efforts are focused on two pharmacological strategies [23]: one directed at abstinence from - or at least substantial reduction of - cocaine use and the other directed at minimizing cocaine-related harm by replacing short-acting, illicit cocaine by a long acting, legal stimulant that can be taken orally [24–26].

Concerning the first strategy, from the wide range of medications tested, topiramate and modafinil are examples of new medications that are currently only registered for indications other than cocaine dependence, but have shown promise in several studies in cocaine dependent populations in terms of abstinence or stimulant use reduction [16, 27, 28].

Topiramate was originally marketed as an anticonvulsant. Through its effects on the GABA- and the glutamate-system, it attenuates dopamine neurotransmission. In the alcohol field, various randomised controlled trials have shown that topiramate was more effective than placebo in treating alcohol dependence [29–31], and was at least as effective as naltrexone [29, 30]. Concerning cocaine, topiramate was more effective in promoting abstinence and sustained abstinence in (crack-) cocaine users in a double-blind placebo-controlled pilot trial of Kampman and colleagues [32], and cocaine craving significantly decreased after the administration of topiramate in an open label trial [33]. A second promising treatment option is the use of the alpha-adrenergic/glutamate agonist modafinil, which is generally prescribed for the treatment of narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea and shift work sleep disorder. In addition, modafinil showed effectiveness in terms of duration of abstinence in the treatment of cocaine dependence in two randomised controlled trials [34, 35], and in the reduction of craving in cocaine dependent patients without comorbid alcohol dependence [36]. More recently, modafinil was investigated in methamphetamine dependence with improved treatment retention and decreased methamphetamine use as a result [37–40].

With respect to the second strategy, harm reduction or drug use reduction oriented treatment, a growing number of pre-clinical and human studies suggest that the monoamine releaser dexamphetamine, used for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy, is an important candidate for replacement therapy [18, 28]. The basic rationale for substitution treatment for cocaine dependence is similar to that for other addictions (nicotine replacement therapy in nicotine dependence, methadone and buprenorphine in opioid dependence): it aims to replace uncontrolled and harmful drug use with regulated and safer use, in terms of dose, route of administration and adverse effects, and to facilitate engagement with health care services by attracting and retaining addicted individuals in treatment [41, 42]. In addition, the regular supervised prescription regimen may by itself help patients to structure their daily life. In cocaine dependent patients several controlled studies have shown significant improvements associated with the administration of sustained-release (SR) dexamphetamine, without serious adverse events (including no serious cardiovascular complications). Shearer and colleagues [43] reported positive results of dexamphetamine SR in a placebo-controlled study of cocaine dependent injectors in terms of reduced cocaine use, craving, severity of dependence and delinquent behaviour, and dexamphetamine SR was found to attenuate cocaine use and improve treatment retention in combined cocaine and heroin dependent patients in controlled studies of Greenwald et al. [44] and Grabowski et al. [45, 46].

In sum, cocaine dependency is characterized by its chronic and relapsing nature and by high treatment dropout rates. A wide range of pharmacological agents has been tested for efficacy in cocaine dependence, but generally with disappointing or, at best, equivocal results. From the investigated candidate medications, topiramate, modafinil and dexamphetamine SR have shown the most promising results. The vast majority of these studies were conducted in the US, however, and therefore these study findings need to be confirmed in research outside the US.

The overall objective of the current study is to investigate topiramate, modafinil, and dexamphetamine SR for their acceptability and effectiveness in the treatment of cocaine dependent patients in The Netherlands. Dependent on the results, this study will also yield candidate medications for further investigation in a large-scale confirmatory trial. More specifically, we aim to evaluate in three separate randomised controlled, open-label, parallel-group feasibility trials in crack-cocaine dependent patients the response to each of these three medications, as an add-on to psychosocial treatment with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), compared to CBT alone, in terms of acceptance, treatment retention and compliance, efficacy, safety, and patient satisfaction. As in any medication study, our primary focus is on the balance between (potential) benefit and harm associated with the medications, taking into consideration the personal and societal damage linked to continued illicit use of cocaine, in a situation without effective pharmacological treatment options.

Because of the aim of the study - investigating treatment effectiveness with both abstinence and harm minimisation as treatment strategies for cocaine dependent patients - the study is named CATCH: Cocaine Addiction Treatments to improve Control and reduce Harm.

Methods/Design

Research design

In each of the three sub-studies, patients are randomly assigned to an experimental or control condition. Patients in both conditions receive basic psychosocial treatment in the form of outpatient cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), and those in the experimental group receive pharmacotherapy with one of the proposed medications as an add-on to CBT.

In the largest series of studies of pharmacological treatment options for cocaine dependence conducted to date, the Cocaine Rapid Efficacy Screening Trials (CREST), a randomised, controlled, parallel group, double-blind design with an unmatched placebo was used in all studies [47]. However, dropout rates in the control groups were observed earlier during the active treatment period, probably caused by inefficacy, and may have biased outcomes (see [15, 48]).

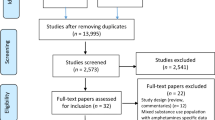

To avoid premature dropout by disappointment about the absence of pharmacological effects in the control groups, we decided not to use the conventional double-blind placebo-controlled design. Instead, we opted for a design in which patients in the control conditions are unaware of the comparative experimental condition in which patients are prescribed active medication. Central feature of this so-called pre-randomisation (or 'Zelen') design [49] is that randomisation takes place prior to seeking (final) informed consent. The variant we use is the so-called double-consent design. Compared to the conventional randomised design, the pre-randomisation double-consent design offers the advantage of providing a more naturalistic control condition, without information or selection bias due to patients being aware that they are control subjects, but with the strengths of a randomised design. The double-consent design is considered particularly useful if the experimental intervention is expected to be attractive to the participants, which is likely to result in considerable disappointment, non-compliance and loss to follow-up among control subjects in a conventional randomised design.

All study participants are asked to provide informed consent to participate in the psychosocial treatment (CBT). After obtaining the (first) informed consent, these patients are randomised to the experimental or control condition, and only those in the experimental condition are asked to provide a second informed consent to participate in the additional pharmacological treatment. Hence, patients are only informed about the assigned treatment, but not about the comparison treatment. In Figure 1 the stepwise procedure according to the pre-randomisation double-consent design is displayed.

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam, the Netherlands (protocol number MEC 09/197).

Participants - setting

Since the use of crack-cocaine is most prevalent in the urban western areas of the Netherlands, the three sub-studies are executed at treatment sites in the three largest Western cities. In The Hague, topiramate is investigated at Brijder Addiction Treatment; in Amsterdam, modafinil is investigated at Arkin; and in Rotterdam, dexamphetamine SR is investigated at Bouman GGZ.

In all three sub-studies, eligible patients must (a) be at least 18 years old, (b) be cocaine dependent (DSM-IV) during at least the previous year, (c) use cocaine on a regular basis (i.e., ≥ 8 days) in the previous month, (d) administer their illicit cocaine primarily by means of basing ('crack'), (e) be able and willing to participate in outpatient psychosocial treatment and associated assessments (control condition), or be able and willing to participate in outpatient psychosocial treatment supplemented with the study medication and associated assessments (experimental condition), and (f) have provided written informed consent with regard to their assigned study treatment.

Patients are excluded in case of (a) severe medical (e.g., severe renal insufficiency; cardiovascular problems) or severe psychiatric problems (e.g. acute psychosis, current major depression, suicidality) that constitute a contra-indication for participation, (b) pregnancy or continued lactation, (c) indication for treatment with naltrexone, disulfiram, acamprosate, methylphenidate or baclofen, (d) indication for residential treatment (clinical judgment), (e) insufficient command of the Dutch language, and (f) current participation in another addiction treatment trial.

Given the nature of the medication and the social debate on the use of dexamphetamine for the treatment of cocaine dependence, in the sub-study with dexamphetamine SR, the required duration of cocaine dependency is at least five years instead of one year. Furthermore, these patients have to meet one additional inclusion criterion: (g) a history of at least two failed treatments directed at reduction of or total abstinence from cocaine use ('treatment-refractory').

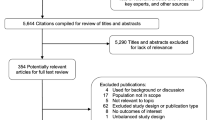

Recruitment & Screening

Study participants are either new referrals to the addiction treatment service with cocaine dependence as their main problem or patients with cocaine dependence already in treatment for another type of dependence, e.g. methadone treatment for opioid dependence.

There are two eligibility screening sessions. In the first session, the CATCH-study is explained and initial eligibility criteria are examined. Study information and informed consent forms are given to read before the second screening session generally one week later. In addition, baseline measurements are conducted.

In the second session, final eligibility is determined by a physician, based on the health and medical status. Eligible patients that agree to participate in the outpatient psychosocial treatment (CBT) and study assessments are asked to provide written informed consent. After this (first) informed consent is obtained, patients are randomised to one of the treatment conditions, i.e. with or without pharmacotherapy. Patients in the experimental group are then notified about the possibility to receive pharmacological treatment as an add-on to CBT, and are informed about the study medication and associated study procedures. Only from these patients, a second informed consent is obtained in a follow-up meeting with the physician, usually one week later.

Psychosocial treatment

CBT in the experimental and control condition incorporates a combination of outpatient cognitive behavioural counselling, relapse prevention and motivational interviewing, which is considered a standard substance abuse treatment in the Netherlands ("Leefstijltraining") [50]. CBT is delivered in 12 weekly individual sessions of 45-minutes by an experienced psychologist who received formal training in CBT for the purpose of the trial. Dependent on the treatment goal of the individual patient, treatment is directed at stabilisation and harm reduction, reduction of cocaine use, or total abstinence.

Pharmacological treatments

Each of the three proposed medications is prescribed for a period of 12 weeks as an add-on to CBT in the experimental group. Topiramate is titrated within three weeks to a maximum oral dose of 200 mg/day, depending on the profile of adverse events observed. During the first treatment week, topiramate is prescribed on a daily basis at the treatment centre. In the remaining trial period, topiramate is dispensed to the patient once a week, i.e. with take-home doses for a maximum of seven days.

Modafinil is prescribed in a fixed oral dose of 200 mg/day during the first treatment week and in a maximum dose of 400 mg/day during the remaining treatment weeks. The prescription regimen of modafinil is similar to that of topiramate (see above).

Dexamphetamine sulphate is prescribed in sustained-release (SR) form, in a daily, oral fixed, dose of 60 mg. To allow more intense safety monitoring and to prevent diversion, dexamphetamine is prescribed on a daily basis at the treatment centre during the first four weeks of the trial period. In the remaining trial period, dexamphetamine is dispensed twice a week (take home doses for a maximum of three days). In addition, during the first four weeks daily assessments of heart rate and blood pressure are conducted, whereas in the remaining treatment period assessments of heart rate and blood pressure take place two times per week.

Assessments and instruments

Study assessments take place at baseline and at four, eight (experimental group only) and 12 weeks (endpoint) following baseline. Table 1 gives an overview of the instruments to be applied at baseline and follow-up assessment points.

At baseline, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM) [51] is used to obtain DSM-IV [52] past year diagnoses of cocaine use disorder and other substance use disorders, the subsection 'suicidal risk' of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) to determine possible suicidality [53–55], and the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) [56] to assess baseline demographics and clinical characteristics.

At baseline and all subsequent time points, the Time Line Follow-Back (TLFB) calendar method [57] is administered to collect detailed information about the patients' self-reported cocaine use during the period preceding each assessment. The short version of the Obsessive Compulsive Drug Use Scale (OCDUS) is used to measure cocaine craving [58–60], the Maudsley Addiction Profile-Health Symptoms Scale (MAP-HSS) [61] to assess physical status, and the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) [62] to identify psychological problems.

All assessments following baseline are supplemented with substance use items of the ASI and questions about current illegal activities, income, and living arrangements.

At the end of the study period (week 12), the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) [63], supplemented with questions about the received psychosocial and pharmacological (experimental groups only) treatment is added to assess patient satisfaction. Treatment adherence is defined as the number of attended CBT sessions.

All these assessments are administered by specially trained research assistants.

Medical assessments are conducted by a physician or laboratory personnel and include: blood pressure, heart rate, blood tests, ECG (dexamphetamine study only) and a pregnancy test (women only) for all participants at baseline. Participants of the experimental groups also receive a weekly medical screening (dexamphetamine study daily in the first four weeks), including blood pressure and heart rate, and women are tested for pregnancy monthly (see Table 1). At week 12, medical status of all participants is evaluated, including blood tests and ECG (dexamphetamine study only) for the experimental groups.

Urine samples are collected by research assistants at baseline, and at the four weeks preceding the endpoint assessment, and are analysed on the presence of benzoylecgonine (BE).

Remuneration

Patients receive a remuneration for their participation: €30 for the baseline assessment, €15 for follow-up assessments after four and eight weeks (experimental groups only), and €30 for the endpoint assessment after 12 weeks. In addition, patients receive €15 for each urine sample provided during the four weeks preceding endpoint assessment. The maximum remuneration is €150 in the experimental group and €120 in the control group.

Outcome measures and data analyses

The study data are analysed following an intent-to-treat (ITT) approach. The ITT-population consists of all patients who provide informed consent pertaining to the assigned treatment.

The primary outcome measure is treatment retention, defined as the number of attended CBT sessions following the start of treatment. In each sub-study, treatment groups are compared on duration of treatment until (premature or planned) termination, using a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Compliance with the study medication can only be investigated in the experimental treatment conditions.

Secondary effects of the interventions are evaluated in terms of treatment compliance, safety, cocaine use (self-report; urinalyses), cocaine craving, use of other substances, physical and mental health, social functioning (including criminality), and patient satisfaction. Pre- to post-treatment changes in days of cocaine use from baseline to week 12 are compared between the two study groups in each sub-study using a 2 (time) × 2 (group) repeated measures ANOVA. Similar analyses are conducted for changes in substance use other than cocaine, and for other continuous and Likert-scaled outcome measures.

Concerning the results of urinalyses, the outcome measure is the sum of BE negative urine samples during the four weeks preceding the endpoint assessment considering missing urine samples as positive. Negative BE urines are compared between the two study groups and evaluated for significant differences by means of an analysis of variances model with the baseline urine sample as covariate.

Following the analyses pertaining to each of the three sub-studies, the datasets from the sub-studies are pooled to further explore the prognostic value of various patient baseline characteristics with increased power.

Safety

Adverse events (AEs) are defined as any undesirable medical experience occurring to a study subject during the study. All AEs reported spontaneously by the subject or observed by the treating physician or his staff are registered on a weekly basis by the treating physician, defining the relationship of each AE with the study medication (definitely not, possibly, probably, certainly, unknown), and its severity. If the AE is considered severe, it is registered as a serious adverse event (SAE). All AEs will be followed until they have abated, or until a stable situation has been reached. If the AE is related to the study medication, it is defined as an adverse reaction (AR) or - if severe - a serious adverse reaction (SAR). An AR can be unexpected when the nature or severity is not consistent with the information in the study medications' summary of product characteristics. SAEs and SARs will be annually reported to the medical ethical committee and the medicine evaluation board.

SAEs that are both unexpected and at least possibly related to the study medication are defined as suspected unexpected serious adverse events (SUSARs). SUSARs that arise during the study are reported within 15 days after the first knowledge of the SUSAR, or within 7 days in case of a fatal or life-threatening SUSAR to the medical ethical committee and the medicine evaluation board of the Netherlands.

Power considerations

In the primary analysis, treatment effect is investigated by means of a Cox proportional hazards regression model. With a difference in 12-week survival between the medication and control groups of 25% (i.e. 45% vs. 20%; hazard rate of 0.066 in the experimental condition vs. 0.135 in the control condition), power of 0.80, and two-sided alpha = 0.10, 36 patients are required in each study group (2 × n = 36 in each medication sub-study; total n = 3 × 2 × 36 = 216 patients). Given the feasibility character of the study, as well as to enable testing of various medications in one study, the sample sizes per trial are necessarily limited. As in the earlier mentioned CREST project, a lenient alpha of 0.10 was chosen to minimize loss of statistical power due to small sample sizes, instead of the usual 5% false-positive rate, which would be more appropriate for future confirmatory trials. Moreover, some earlier studies of modafinil and dexamphetamine SR in cocaine addicts found significant results with comparable sample sizes [34, 43, 45, 46].

Discussion

Given the considerable number of problematic crack-cocaine users and the lack of effective psychosocial and pharmacological treatments, the CATCH-study is the first study in the Netherlands that explores new pharmacological treatment options for this type of addiction that are not only focused on abstinence (CBT with or without topiramate or modafinil), but also on harm minimization using an agonist approach (CBT with or without dexamphetamine SR). It is expected that the study will contribute to opening up new lines of research and - dependent upon the results - new lines of treatment for one of the most problematic substance use disorders: crack-cocaine dependence.

A limitation of this study is that control patients will not receive placebo (in addition to their CBT) and that experimenters' bias towards the medication group can not be eliminated due to the open-label design. However, given the high dropout rates in controls such as in the CREST-studies, these disadvantages are defendable in the context of the proposed feasibility trials.

References

Inciardi JA, Surratt HL: Drug use, street crime, and sex-trading among cocaine-dependent women: implications for public health and criminal justice policy. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2001, 33 (4): 379-389. 10.1080/02791072.2001.10399923.

Miller NS, Gold MS, Mahler JC: Violent behaviors associated with cocaine use: possible pharmacological mechanisms. Int J Addict. 1991, 26 (10): 1077-1088.

Bennett T, Brookman F: The role of violence in street crime: a qualitative study of violent offenders. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2009, 53 (6): 617-633. 10.1177/0306624X08323158.

Trimbos-instituut: Nationale drugmonitor - Jaarbericht 2009. 2010, Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut

IVZ: Kerncijfers verslavingszorg 2009. 2010, Houten: Stichting Informatie Voorziening Zorg

Shearer J: Psychosocial approaches to psychostimulant dependence: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007, 32 (1): 41-52. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.012.

Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW: A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008, 165 (2): 179-187. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851.

Van Horn DH, Drapkin M, Ivey M, Thomas T, Domis SW, Abdalla O, Herd D, McKay JR: Voucher incentives increase treatment participation in telephone-based continuing care for cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010

Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST: A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006, 101 (2): 192-203. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x.

Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J: Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006, 101 (11): 1546-1560. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x.

Knapp WP, Soares BG, Farrel M, Lima MS: Psychosocial interventions for cocaine and psychostimulant amphetamines related disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, CD003023-3

Bride BE, Abraham AJ, Roman PM: Diffusion of contingency management and attitudes regarding its effectiveness and acceptability. Subst Abus. 2010, 31 (3): 127-135. 10.1080/08897077.2010.495310.

Marteau TM, Ashcroft RE, Oliver A: Using financial incentives to achieve healthy behaviour. BMJ. 2009, 338: b1415-10.1136/bmj.b1415.

Preti A: New developments in the pharmacotherapy of cocaine abuse. Addict Biol. 2007, 12 (2): 133-151. 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00061.x.

Kampman KM, Leiderman D, Holmes T, LoCastro J, Bloch DA, Reid MS, Shoptaw S, Montgomery MA, Winhusen TM, Somoza EC, Ciraulo DA, Elkashef A, Vocci F: Cocaine Rapid Efficacy Screening Trials (CREST): lessons learned. Addiction. 2005, 100 (Suppl 1): 102-110.

Alvarez Y, Farre M, Fonseca F, Torrens M: Anticonvulsant drugs in cocaine dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010, 38 (1): 66-73. 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.07.001.

Soares BG, Lima MS, Reisser AA, Farrell M: Dopamine agonists for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003, CD003352-2

Castells X, Casas M, Perez-Mana C, Roncero C, Vidal X, Capella D: Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010, CD007380-2

Lima MS, Soares BG, Reisser AA, Farrell M: Pharmacological treatment of cocaine dependence: a systematic review. Addiction. 2002, 97 (8): 931-949. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00209.x.

Amato L, Minozzi S, Pani PP, Davoli M: Antipsychotic medications for cocaine dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, CD006306-3

O'Brien CP: Anticraving medications for relapse prevention: a possible new class of psychoactive medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2005, 162 (8): 1423-1431. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1423.

Karila L, Gorelick D, Weinstein A, Noble F, Benyamina A, Coscas S, Blecha L, Lowenstein W, Martinot JL, Reynaud M, Lepine JP: New treatments for cocaine dependence: a focused review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11 (3): 425-438.

American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2007, 164 (4): 1-124.

Shearer J, Merrill J, Negus SS: Agonist-like, replacement pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse and dependence. Addict Behav. 2004, 29 (7): 1439-1464. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.018.

Herin DV, Rush CR, Grabowski J: Agonist-like pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010, 1187: 76-100. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05145.x.

Ross S, Peselow E: Pharmacotherapy of addictive disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009, 32 (5): 277-289. 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181a91655.

Ballon JS, Feifel D: A systematic review of modafinil: Potential clinical uses and mechanisms of action. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006, 67 (4): 554-566. 10.4088/JCP.v67n0406.

Castells X, Casas M, Vidal X, Bosch R, Roncero C, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Capellà D: Efficacy of central nervous system stimulant treatment for cocaine dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Addiction. 2007, 102 (12): 1871-1887. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01943.x.

Baltieri DA, Daro FR, Ribeiro PL, de Andrade AG: Comparing topiramate with naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2008, 103 (12): 2035-2044. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02355.x.

Florez G, Saiz PA, Garcia-Portilla P, Alvarez S, Nogueiras L, Bobes J: Topiramate for the treatment of alcohol dependence: comparison with naltrexone. Eur Addict Res. 2011, 17 (1): 29-36. 10.1159/000320471.

Rubio G, Martinez-Gras I, Manzanares J: Modulation of impulsivity by topiramate: implications for the treatment of alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009, 29 (6): 584-589. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181bfdb79.

Kampman KM, Pettinati H, Lynch KG, Dackis C, Sparkman T, Weigley C, O'Brien CP: A pilot trial of topiramate for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004, 75 (3): 233-240. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.008.

Reis AD, Castro LA, Faria R, Laranjeira R: Craving decrease with topiramate in outpatient treatment for cocaine dependence: an open label trial. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008, 30 (2): 132-135. 10.1590/S1516-44462008005000012.

Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Modafinil for Cocaine Dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005, 30 (1): 205-211. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300600.

Dackis CA, Lynch KG, Yu E, Samaha FF, Kampman KM, Cornish JW, Rowan A, Poole S, White L, O'Brien CP: Modafinil and cocaine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled drug interaction study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003, 70 (1): 29-37. 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00335-6.

Anderson AL, Reid MS, Li S-H, Holmes T, Shemanski L, Slee A, Smith EV, Kahn R, Chiang N, Vocci F: Modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 104 (1-2): 133-139. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.015.

De La Garza R, Zorick T, London ED, Newton TF: Evaluation of modafinil effects on cardiovascular, subjective, and reinforcing effects of methamphetamine in methamphetamine-dependent volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010, 106 (2-3): 173-180. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.013.

Shearer J, Darke S, Rodgers C, Slade T, van Beek I, Lewis J, Brady D, McKetin R, Mattick RP, Wodak A: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil (200 mg/day) for methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2009, 104 (2): 224-233. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02437.x.

McElhiney MC, Rabkin JG, Rabkin R, Nunes EV: Provigil (modafinil) plus cognitive behavioral therapy for methamphetamine use in HIV+ gay men: a pilot study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009, 35 (1): 34-37. 10.1080/00952990802342907.

Heinzerling KG, Swanson A-N, Kim S, Cederblom L, Moe A, Ling W, Shoptaw S: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010, 109 (1-3): 20-29. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.023.

Shearer J, Gowing L: Pharmacotherapies for problematic psychostimulant use: a review of current research. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004, 23 (2): 203-211. 10.1080/09595230410001704190.

Shearer J: The principles of agonist pharmacotherapy for psychostimulant dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008, 27 (3): 301-308. 10.1080/09595230801927372.

Shearer J, Wodak A, van Beek I, Mattick RP, Lewis J: Pilot randomized double blind placebo-controlled study of dexamphetamine for cocaine dependence. Addiction. 2003, 98 (8): 1137-1141. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00447.x.

Greenwald MK, Lundahl LH, Steinmiller CL: Sustained Release d-Amphetamine Reduces Cocaine but not 'Speedball'-Seeking in Buprenorphine-Maintained Volunteers: A Test of Dual-Agonist Pharmacotherapy for Cocaine/Heroin Polydrug Abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010, 35 (13): 2624-2637. 10.1038/npp.2010.175.

Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Stotts A, Cowan K, Kopecky C, Dougherty A, Moeller FG, Hassan S, Schmitz J: Agonist-Like or Antagonist-Like Treatment for Cocaine Dependence with Methadone for Heroin Dependence: Two Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trials. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004, 29 (5): 969-981. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300392.

Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Schmitz J, Stotts A, Daruzska LA, Creson D, Moeller FG: Dextroamphetamine for cocaine-dependence treatment: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001, 21 (5): 522-526. 10.1097/00004714-200110000-00010.

Leiderman DB, Shoptaw S, Montgomery A, Bloch DA, Elkashef A, LoCastro J, Vocci F: Cocaine Rapid Efficacy Screening Trial (CREST): a paradigm for the controlled evaluation of candidate medications for cocaine dependence. Addiction. 2005, 100 (Suppl 1): 1-11.

Elkashef A, Holmes TH, Bloch DA, Shoptaw S, Kampman K, Reid MS, Somoza E, Ciraulo D, Rotrosen J, Leiderman D, Montgomery A, Vocci F: Retrospective analyses of pooled data from CREST I and CREST II trials for treatment of cocaine dependence. Addiction. 2005, 100 (Suppl 1): 91-101.

Zelen M: A new design for randomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 1979, 300 (22): 1242-1245. 10.1056/NEJM197905313002203.

De Wildt WAJM: Leefstijltraining 2. Handleiding trainer (Lifestyle training 2. Trainer treatment manual). 2002, Utrecht (The Netherlands): GGZ Nederland, Resultaten Scoren

Cottler LB: Composite International Diagnostic Interview- Substance Abuse Module (SAM). 2000, St. Louis, MO: Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 1994, 4

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998, 59 (Suppl 20): 22-33. quiz 34-57

McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M: The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992, 9 (3): 199-213. 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-S.

Hendriks VM, Kaplan CD, van Limbeek J, Geerlings P: The Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in a Dutch addict population. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1989, 6 (2): 133-141. 10.1016/0740-5472(89)90041-X.

McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980, 168 (1): 26-33. 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006.

Sobell LC, Sobell MB: Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. edn. Edited by: Litten RZ, Allen J. 1992, New Jersey: Humana Press, 41-72.

de Wildt WA, Lehert P, Schippers GM, Nakovics H, Mann K, van den Brink W: Investigating the structure of craving using structural equation modeling in analysis of the obsessive-compulsive drinking scale: a multinational study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005, 29 (4): 509-516. 10.1097/01.ALC.0000158844.35608.48.

Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham PK: The obsessive compulsive drinking scale: A new method of assessing outcome in alcoholism treatment studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996, 53 (3): 225-231.

Franken IH, Hendriks VM, Van den Brink W: Initial validation of two opiate craving questionnaires the obsessive compulsive drug use scale and the desires for drug questionnaire. Addict Behav. 2002, 27 (5): 675-685. 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00201-5.

Marsden J, Gossop M, Stewart D, Best D, Farrell M, Lehmann P, Edwards C, Strang J: The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP): a brief instrument for assessing treatment outcome. Addiction. 1998, 93 (12): 1857-1867. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9312185711.x.

Arrindell WA, Ettema JHM: SCL-90: Handleiding bij een multidimensionele psychopathologie-indicator. 1986, Lisse: Swets en Zeitlinger

Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann. 1979, 2 (3): 197-207. 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/11/135/prepub

Acknowledgements and funding

This study is funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW). It is a cooperation between two research institutes (Parnassia Addiction Research Centre and Amsterdam Institute for Addiction Research) and three treatment centres (Brijder Addiction Treatment, Arkin and Bouman GGZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

VH and PB created the design of the study and composed the request for funding together with WvdB. MN drafted this paper. All authors revised this manuscript and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nuijten, M., Blanken, P., van den Brink, W. et al. Cocaine Addiction Treatments to improve Control and reduce Harm (CATCH): New Pharmacological Treatment Options for Crack-Cocaine Dependence in the Netherlands. BMC Psychiatry 11, 135 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-135

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-135