Abstract

Background

Studies show great variability in the prevalence of hyperopia among children. This study aimed to synthesize the existing knowledge about hyperopia prevalence and its associated factors in school children and to explore the reasons for this variability.

Methods

This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines. Searching several international databases, the review included population- or school-based studies assessing hyperopia through cycloplegic autorefraction or cycloplegic retinoscopy. Meta-analysis of hyperopia prevalence was performed following MOOSE guidelines and using the random effects model.

Results

The review included 40 cross-sectional studies. The prevalence of hyperopia ranged from 8.4% at age six, 2-3% from 9 to 14 years and approximately 1% at 15 years. With regard to associated factors, age has an inverse association with hyperopia. The frequency of hyperopia is higher among White children and those who live in rural areas. There is no consensus about the association between hyperopia and gender, family income and parental schooling.

Conclusion

Future studies should use standardized methods to classify hyperopia and sufficient sample size when evaluating age-specific prevalence. Furthermore, it is necessary to deepen the understanding about the interactions among hyperopic refractive error and accommodative and binocular functions as a way of identifying groups of hyperopic children at risk of developing visual, academic and even cognitive function sequelae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hyperopia in childhood, particularly when severe and/or associated with accommodative and binocular dysfunctions, may be a precursor of visual motor and sensory sequelae such as accommodative esotropia, anisometropia and unilateral or bilateral amblyopia [1, 2]. Children with hyperopia may also present symptoms related to asthenopia while reading.

Studies have also shown that axial length (AL) of the eye or the relation between AL and corneal curvature (CC) radius plays an important role in the variability of hyperopic spherical equivalent refraction (SE) [3–8]. Utermen observed that after logistic regression, the combination of AL and CC contributed to explaining 60.9% of variability in hyperopic SE among children aged 3 to 14 years on average [5].

Although there are several studies on hyperopia, so far there has been no systematic review of the subject. This systematic review aims to synthesize existing knowledge about the hyperopia prevalence and associated factors among children, followed by a meta-analysis of hyperopia prevalence. This synthesis may help in the design of appropriate public policies to correct hyperopia in children.

Methods

Systematic review

The literature search was performed on MEDLINE (PubMed), Scielo, Bireme, Embase, Cochrane Library, Clinical Trials registration website and WHO databases. The following descriptors were used: refractive errors, hyperopia, prevalence and children, limited to keywords or words in the title or abstract, in either their isolated or combined form. The searches were limited to the 0-18 age range.A total of 701 records were identified and screened (including theses, journals, articles, books, book chapters and institutional reports) relating to hyperopia prevalence in children up to 18 years old. 99 of these articles were duplicated. Population-based or school-based studies assessing hyperopia through cycloplegic autorefraction or cycloplegic retinoscopy were included. 525 papers were excluded owing to their focus on: specific populations as well as publications about refractive errors in subjects with eye diseases (amblyopia, strabismus, glaucoma, corneal abnormalities, chromatic aberrations, accommodative and binocular dysfunction and asthenopia); other specific clinical diseases or conditions (intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, dyslexia and prematurity); ophthalmology/optometry outpatients; genetic and/or congenital alterations; before and/or after examinations, clinical and/or surgical treatment; cost-benefit research and geographically isolated populations. A further 44 articles were excluded due to: non-random sample of the general population and schools; determination of refractive error without cycloplegia; cycloplegia only in children with low vision; hyperopia based only on visual acuity testing, studies without specific cut-off for hyperopia, samples excluding children that were already in eye care treatment, samples based on records of clinics or mobile clinics, very small and stratified samples. 07 papers found in the references of the selected articles were included (Figure 1).

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis was undertaken regarding prevalence of moderate hyperopia at specific ages in 6 to 15 year-olds. Out of a total of 21 articles on hyperopia prevalence at specific ages (Table 1), three had losses of more than 20% and six did not report their response rates. Fotouhi’s study showed prevalence estimates significantly different to all the other studies in various age groups, and its inclusion in the meta-analysis resulted in a statistically significant heterogeneity test (p < 0.05). Based on the heterogeneity assumption for the effect summary, Fotouhi’s study was characterized as an outlier and excluded from the meta-analysis. Following this, the heterogeneity test produced a p-value > 0.1 in all specific ages [9]. Thus the meta-analysis was based on 11 studies assessing moderate hyperopia taking ≥ +2.00D as the cut-off point and a response rate greater than 80% (Table 1).

The meta-analysis was performed using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet [49]. Differences in the populations studied, especially ethnicity, have a non-random impact on prevalence. The random effects model was therefore used in order to obtain the effect summary and its confidence interval. The adequacy of the effect summary depends on the homogeneity assumption. Heterogeneity was measured using the Q test and was quantified using I2 statistics. Heterogeneity tests having a p-value <0.1 were considered statistically significant.

This systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA [50] and MOOSE [51] Statements. The study was approved by the Federal University of Pelotas School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee and follows the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines [52].

Results

Hyperopia prevalence by age in children

The review included 40 cross-sectional studies on prevalence and/or assessment of risk factors for hyperopia. Eighteen studies were conducted in Asia, of which six were carried out in China and five in India. The other Asian countries were: Nepal (three studies), Malaysia (two studies), Cambodia and the Democratic Republic of Laos (one study each). Seven studies are from Europe (two were conducted in the United Kingdom; Poland and Sweden carried out two studies each and one study was conducted in Finland). Six studies are from the Middle East (Iran). Four studies were conducted in Australia, two in the United States and one study each in South Africa, Chile and Mexico.

All samples of children used in the studies were population-based or school-based, except the study that used a sample of children from a private school in Xiamen, China [13].

In most studies included in this review, the cut-off point for hyperopia was based on the Refractive Error Study in Children (RESC) protocol used in multicenter studies [53]. Spherical equivalent refraction (SE) for hyperopia was ≥ +2.00D (one or both eyes, if none the eyes are myopic). The studies used data from one or both eyes to determine prevalence. However, some studies used different cut-off points [38–48, 54], thus underestimating or overestimating hyperopia prevalence compared to studies using the RESC protocol. Some studies performed the examination on the right eye only, thereby underestimating the prevalence of hyperopia [38, 43].

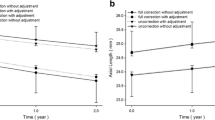

The meta-analysis indicates that hyperopia prevalence decreases as age increases, with a summary prevalence measure of 5% at age 7, 2-3% between age 9 and 14 and around 1% at age 15. Various studies of children aged 6 to 8 presented large confidence intervals. I2 indicates homogeneity among the studies regarding specific age (Figure 2).

In studies using the 5-15 age group and ≥ +2.00 D (RESC) cut-off, hyperopia prevalence ranged from 2.1% [18] to 19.3% [25, 37] (Table 1).

Although there is literature indicating a direct association between AL and age, only a few studies have assessed its distribution by specific ages [40, 55].

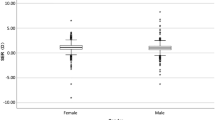

Gender and hyperopia in children

Most studies showed no statistically significant association between gender and hyperopia (Table 2) [9, 11, 14, 17, 19, 20, 23, 25–27, 30, 32, 34, 36, 39–41, 46–48, 56, 57]. With regard to ocular components, on average girls appear to have shorter AL when compared to boys [3, 30, 55, 58].

According to some studies however, girls are more likely to be hyperopic when compared to boys. In Australia, girls aged 6 are more likely to be hyperopic (15.5%) (95% CI 12.7-18.4) than boys of the same age (10.9%) (95% CI 8.5-13.2) (p = 0.005), although this difference was not found among children aged 12 in the same study [29]. Similarly, studies conducted in Chile, China and Nepal with children aged 5-15 years showed that girls are more likely to be hyperopic than boys: OR = 1.21 (95% CI 1.03-1.43) [37], OR = 1.51 (95% CI 1.08-2.13) [10] and OR = 1.44 (95% CI 1.02-2.03), [18] respectively. However, in a study conducted in Poland boys aged 6-18 years showed higher hyperopia prevalence (40.3%) (95% CI 38.5-42.1) when compared to girls in the same age range (35.3%) (95% CI 33.6 - 37.0) [43].

Ethnicity and hyperopia in children

Some studies have shown that there is no significant difference in hyperopia prevalence between Caucasian and Hispanic children [39] or between Caucasian and Middle East children [29, 30]. There is also evidence that Caucasian children are more hyperopic than African-American [39, 54, 56, 61], Black [35] and Asian (East and South Asia) children [29, 30, 35]. With regard to specific ethnic groups, there is no difference between hyperopia prevalence among Malay, Chinese and Indian children [17], although Malaysian children are more hyperopic than Singaporean (p = 0.005) [16] and Melanesian children [60]. It was also found that children of other ethnicities (not specified) are more likely to be hyperopic than Melanesian children OR = 3.72 (95%CI 1.34-10.3) [17] (Table 2).

In the South African study, hyperopia prevalence among children aged 7 years was only 2.8% [36]. The majority of the South African population is Black, followed by Asians (9.4%) and Caucasians (6.6%). In the Malay study, hyperopia prevalence among children aged 10 years was 1.4% [17]. The ethnic composition of the region is mostly Malay but approximately 28% of individuals have Chinese origin. The lowest hyperopia prevalence (0.5%) was found in a study in Guangzhou, one of the most developed cities in southern China [11].

Regarding ocular components in different ethnicities, on average it was found that AL is shorter and CC is flatter among Caucasian children [3, 30, 62].

Parental education and socio-economic status and hyperopia in children

Most of the reviewed studies showed no significant association between parental education and hyperopia in children (Table 2) [16, 17, 21, 22, 27, 36, 47]. In an Australian study, although there was no significant association between paternal education and hyperopia among children under 6 years of age, maternal education showed an inverse association with the presence of hyperopia among children aged 12 (p = 0.055) [29]. In a Chinese study the high level of parental education was a protective factor against the presence of hyperopia among children aged 5-15 years, OR = 0.81 (95% CI 0.73 - 0.81) [11].

Regarding socio-economic status, maternal employment is directly related to hyperopia in 6-year-old children in Australia (p = 0.02), although it is not associated with family income or paternal employment (p > 0.1) [29]. In the same study, an association between both parents being employed and hyperopia ≥ +2.00 D was found among 6-year-old children, after adjusting for gender, ethnicity and parental education (p = 0.02) [29].

Each of the three Indian studies with children aged 0-15 years had different cut-offs for hyperopia (≥ + 2.00D, ≥ + 1.00D and ≥ +0.5 D) but none of them showed association between socio-economic status (classified according to family income) and hyperopia [22, 41, 47].

In a study conducted in the United States, children aged 6-72 months with health insurance coverage showed a greater chance of having hyperopia when compared to those with no health insurance, OR = 1.51 (95% CI 1.12 - 1.69) [61].

Area of residence and hyperopia in children

There are few studies on the association between area of residence (urban or rural) and hyperopia prevalence in children. In an Indian study, children aged 0-15 years who lived in two rural areas were more likely to be hyperopic when compared to those living in urban areas, OR = 2.84 (95% CI 2.16-3.75) and OR = 1.50 (95% CI 1.17-1.92) respectively (Table 2) [47]. In another study conducted in India with children aged 7-15 years, those aged 8, 9, 12 and 13 years living in rural areas presented higher prevalence of hyperopia than those of the same age living in urban areas (Table 2) [23].

An Iranian study showed that children aged 7-15 years living in rural areas are more likely to be hyperopic than those living in urban areas, OR = 2.0 (95% CI 1.09-3.65) [9] and another study in Poland reported that children aged 6-18 years living in urban areas showed lower frequency of hyperopia when compared to children living in rural areas (p < 0.001) (Table 2) [38].

Two reviewed articles (one conducted in China with children aged 6-7 years and the other in Cambodia with children aged 12-14 years) showed no significant association between area of residence and hyperopia [13, 19] In the Cambodian study, hyperopia prevalence rates among children living in urban and rural areas were 1.4% (95% CI 0.1 - 1.7) and 0.4% (95% CI 0.1 - 1.9) respectively (Table 2) [19].

Outdoor activities and hyperopia in children

Rose et al. noted that children aged 6 and 12 years in Australia who spent more time per week doing outdoor activities (outdoor sports, picnics and walking) were more hyperopic than those who spent less time practicing these activities, adjusted for gender, ethnicity, presence of myopia in parents, near activities, and maternal and paternal education and working mothers (p = 0.009 and p = 0.0003, respectively) (Table 2) [8]. These authors also noted that there was a statistically significant trend toward greater hyperopic spherical equivalent refraction as tertiles of outdoor activities increased and tertiles of near activities decreased [8]. In the same study, Rose concluded that hyperopic spherical equivalent refraction was more common in children who dedicated less time to near activities and more time to outdoor activities [8].

Spending time engaged in outdoor activities was slightly associated with hyperopia (β = 0.03, p < 0.0001) among 12-year-old children in Australia. That study found that children who performed near activities (reported by parents), such as reading distance (<30cm), were significantly associated with less hyperopia (p < 0.0001), after adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity and type of school (Table 2) [59].

In the United States, Mutti et al. examined 366 children with mean age of 13.7 ± 0.5 years and showed (using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test) that myopic children spend more time reading for pleasure (p = 0.034) and less time playing sports (p = 0.049) compared with hyperopic children [7].

Discussion

There are several studies on hyperopia prevalence in childhood, but a great difficulty arises when attempting to compare them. This is partly due to the methodological characteristics of each study. Regarding the diopter value, there is no consensus on the cut-off point for diagnosing children as hyperopic, nor on what is the most appropriate measure: a greater, or lesser, hyperopic corneal meridian or spherical equivalent refraction [2]. However, cycloplegia followed by retinoscopy or autorefraction is the acceptable way of testing to diagnose ametropias, although doubts remain as to its accuracy in children with darker irises [63]. Most studies classify an individual as being hyperopic after binocular examination, but others use the eyes separately as unit samples or examine only one of the eyes (usually the right eye) relying on evidence of good correlation between ametropia in both eyes [2].

The RESC protocol has been used as a way of standardizing the methodology applied in studies on refractive errors, thus improving the comparability of results between child populations [53]. Hyperopia has an inverse association with age, is more common in Caucasian children and in those who live in rural areas or spend more time doing outdoor activities and it shows inconsistent results regarding association with gender, socio-economic status and parental education.

There is consistency among the studies about the inverse association between hyperopia and age. Although there are studies stating that slow growth in AL lasts until around the age of 12-14 years [5, 55, 64], emmetropization is minimal after the age of three, [6] and does not explain the decrease in hyperopia by age after 5 years-old.

Studies included in the meta-analysis were selected due to their methodological similarity and high response rate. The larger confidence intervals among those aged 6 to 8 indicate a less precise estimate of prevalence which is related to smaller sample size in these specific ages. However, it might also reflect greater difficulty in performing examinations in younger children, or greater variability in different populations in this age range, such as the heredity of refractive error or ocular characteristics of components such as axial length among different ethnicities.

The conflicting results when assessing the association between gender and hyperopia may be related to gender representativeness in the studies. On the one hand, the gender ratio is fairly even, suggesting good representativeness. Yet in some cultures girls have more difficulty in accessing schools, which could imply selection bias in hyperopia prevalence. On the other hand, females have greater acceptance and participation in studies, trials and interviews with scientific purposes which in turn could lead to positive selection bias [25].

The particularly low hyperopia prevalence could be partly explained by ethnicity, such as in Durban, South Africa [36], where the majority of the population are Black, followed by Asians. Regarding ocular components, axial length in both Africans and Asians is longer than in Caucasian individuals.

Literature shows that populations with high myopia prevalence rates generally have low hyperopia prevalence, as in China [11, 30]. This aspect may influence the prevalence of hyperopia in places where there is a considerably high density of Chinese ethnicity when compared to the native population, as in Durban and Gombak [17, 36].

No association was found between parental education and socio-economic status and hyperopia in children. As for ocular components, in the United States Lee observed a statistically significant association (p < 0.01) between years of education and larger AL in individuals aged 43-84 years, indicating that this aspect should be better studied in children [65].

Some authors point to geographical factors as potential determinants of ametropias, such as location and type of residence. They defend that greater levels of hyperopia may be found in people who live in rural areas and in houses, because they do more outdoor activities.

The controversy as to the impact of environmental factors on hyperopic spherical equivalent refraction in children still remains. Although theoretically near activities increase the demand of the accommodative process (hyperopic defocus), stimulating changes in the dimensions of ocular components (such as increases in AL) and thus decreasing the eye’s chance of remaining hyperopic [6], one cross-sectional study found very weak correlation between hours spent in near work activities and spherical equivalent [59]. Regarding outdoor activities, spending more time outdoors was associated with slightly more hyperopic refractions [59]. Theoretically, children who spend more hours per week doing outdoor activities do not require as much accommodation to practice them. Thus, the stimulation of ocular growth decreases owing to low accommodative demand [8]. The empirical evidence is insufficient to be able to understand the relationship between environmental factors and hyperopia.

The role of light intensity must also be considered. Since light is usually of greater intensity outdoors, eye exposure results in a more constricted pupil, increasing the depth of focus and leading to a less unfocused image [8]. In addition, dopamine released by light stimulus on the retina can contribute directly to inhibiting ocular growth [8, 66].

Conclusion

The large variability of hyperopia prevalence raises questions about the ability of demographic, socio-economic and environmental factors to completely explain the hyperopia causal chain. Considering that more myopic populations or those with earlier onset of myopia may be populations with earlier or greater reductions in hyperopia, in view of the complementarity of these phenomena, the causes of the decrease in hyperopia prevalence may be common to those explaining the increase in myopia with age.

Future studies should refine the evaluation of these factors, particularly the role of outdoor activities and ethnicity, as well as exploring other potential risk factors such as heredity or diet. In order to improve the consistency of analysis, refractive error measurement needs to be standardized using the RESC Protocol and using cycloplegia to perform refractive examination. It is also important to have population-based or school-based representative samples, with low percentages of loss to follow-up and sufficiently large samples to be able to stratify by specific age. More studies on those younger than 9 years-old and with larger samples are necessary in order to obtain a more precise prevalence estimate.

AAO recommends undercorrection of hyperopia, however despite the fact that a large percentage of hyperopia appears to be benign at very early ages, a significant number may go on to develop sequelae. Furthermore, it is necessary to deepen the understanding about the interactions among hyperopic refractive error and accommodative and binocular functions as a way of identifying groups of hyperopic children at risk of developing visual, academic and even cognitive function sequelae [2].

References

Rosner J: The still neglected hyperope. Optom Vis Sci. 2004, 81 (4): 223-224. 10.1097/00006324-200404000-00001.

Tarczy-Hornoch K: The epidemiology of early childhood hyperopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2007, 84 (2): 115-123. 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318031b674.

Ojaimi E, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Smith W, Martin FJ, Kifley A, Robaei D, Mitchell P: Distribution of ocular biometric parameters and refraction in a population-based study of Australian children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005, 46 (8): 2748-2754. 10.1167/iovs.04-1324.

Klein AP, Suktitipat B, Duggal P, Lee KE, Klein R, Bailey-Wilson JE, Klein BE: Heritability analysis of spherical equivalent, axial length, corneal curvature, and anterior chamber depth in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009, 127 (5): 649-655. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.61.

Uretmen O, Pamukcu K, Kose S, Egrilmez S: Oculometric features of hyperopia in children with accommodative refractive esotropia. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003, 81 (3): 260-263. 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00062.x.

Mutti DO: To emmetropize or not to emmetropize? The question for hyperopic development. Optom Vis Sci. 2007, 84 (2): 97-102. 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318031b079.

Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Moeschberger ML, Jones LA, Zadnik K: Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children's refractive error. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002, 43 (12): 3633-3640.

Rose KA, Morgan IG, Ip J, Kifley A, Huynh S, Smith W, Mitchell P: Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2008, 115 (8): 1279-1285. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019.

Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K: The prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Dezful, Iran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007, 91 (3): 287-292. 10.1136/bjo.2006.099937.

Zhao J, Pan X, Sui R, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein LB: Refractive Error Study in Children: results from Shunyi District, China. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000, 129 (4): 427-435. 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00452-3.

He M, Zeng J, Liu Y, Xu J, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB: Refractive error and visual impairment in urban children in southern china. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004, 45 (3): 793-799. 10.1167/iovs.03-1051.

Fan DS, Lam DS, Lam RF, Lau JT, Chong KS, Cheung EY, Lai RY, Chew SJ: Prevalence, incidence, and progression of myopia of school children in Hong Kong. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004, 45 (4): 1071-1075. 10.1167/iovs.03-1151.

Zhan MZ, Saw SM, Hong RZ, Fu ZF, Yang H, Shui YB, Yap MK, Chew SJ: Refractive errors in Singapore and Xiamen, China–a comparative study in school children aged 6 to 7 years. Optom Vis Sci. 2000, 77 (6): 302-308. 10.1097/00006324-200006000-00010.

Pi LH, Chen L, Liu Q, Ke N, Fang J, Zhang S, Xiao J, Ye WJ, Xiong Y, Shi H, Yin ZQ: Refractive status and prevalence of refractive errors in suburban school-age children. Int J Med Sci. 2010, 7 (6): 342-353.

He M, Huang W, Zheng Y, Huang L, Ellwein LB: Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in rural southern China. Ophthalmology. 2007, 114 (2): 374-382. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.020.

Saw SM, Goh PP, Cheng A, Shankar A, Tan DT, Ellwein LB: Ethnicity-specific prevalences of refractive errors vary in Asian children in neighbouring Malaysia and Singapore. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006, 90 (10): 1230-1235. 10.1136/bjo.2006.093450.

Goh PP, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB: Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology. 2005, 112 (4): 678-685. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.048.

Pokharel GP, Negrel AD, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB: Refractive Error Study in Children: results from Mechi Zone, Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000, 129 (4): 436-444. 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00453-5.

Gao Z, Meng N, Muecke J, Chan WO, Piseth H, Kong A, Jnguyenphamhh T, Dehghan Y, Selva D, Casson R, Ang K: Refractive error in school children in an urban and rural setting in Cambodia. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012, 19 (1): 16-22. 10.3109/09286586.2011.632703.

Casson RJ, Kahawita S, Kong A, Muecke J, Sisaleumsak S, Visonnavong V: Exceptionally Low Prevalence of Refractive Error and Visual Impairment in Schoolchildren from Lao People's Democratic Republic. Ophthalmology. 2012, 119 (10): 2021-7. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.049.

Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Ellwein LB, Munoz SR, Pokharel GP, Sanga L, Bachani D: Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002, 43 (3): 623-631.

Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M, Sahare P, Narsaiah S, Munoz SR, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB: Refractive error in children in a rural population in India. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002, 43 (3): 615-622.

Uzma N, Kumar BS, Khaja Mohinuddin Salar BM, Zafar MA, Reddy VD: A comparative clinical survey of the prevalence of refractive errors and eye diseases in urban and rural school children. Canadian journal of ophthalmology Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2009, 44 (3): 328-333. 10.3129/i09-030.

Hashemi H, Iribarren R, Morgan IG, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K, Fotouhi A: Increased hyperopia with ageing based on cycloplegic refractions in adults: the Tehran Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010, 94 (1): 20-23. 10.1136/bjo.2009.160465.

Ostadimoghaddam H, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Yekta A, Heravian J, Rezvan F, Ghadimi H, Rezvan B, Khabazkhoob M: Prevalence of the refractive errors by age and gender: the Mashhad eye study of Iran. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2011, 39 (8): 743-751. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02584.x.

Rezvan F, Khabazkhoob M, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, Azizi E, Khorasani AA, Yekta AA: Prevalence of refractive errors among school children in Northeastern Iran. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012, 32 (1): 25-30. 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00879.x.

Yekta A, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Dehghani C, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, Derakhshan A, Yekta R, Behnia M, Khabazkhoob M: Prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Shiraz, Iran. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010, 38 (3): 242-248.

Robaei D, Rose K, Ojaimi E, Kifley A, Huynh S, Mitchell P: Visual acuity and the causes of visual loss in a population-based sample of 6-year-old Australian children. Ophthalmology. 2005, 112 (7): 1275-1282. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.01.052.

Ip JM, Robaei D, Kifley A, Wang JJ, Rose KA, Mitchell P: Prevalence of hyperopia and associations with eye findings in 6- and 12-year-olds. Ophthalmology. 2008, 115 (4): 678-685. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.061. e671

Ip JM, Huynh SC, Robaei D, Kifley A, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Wang JJ, Mitchell P: Ethnic differences in refraction and ocular biometry in a population-based sample of 11-15-year-old Australian children. Eye. 2008, 22 (5): 649-656. 10.1038/sj.eye.6702701.

Robaei D, Kifley A, Rose KA, Mitchell P: Refractive error and patterns of spectacle use in 12-year-old Australian children. Ophthalmology. 2006, 113 (9): 1567-1573. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.066.

Gronlund MA, Andersson S, Aring E, Hard AL, Hellstrom A: Ophthalmological findings in a sample of Swedish children aged 4–15 years. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006, 84 (2): 169-176. 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00615.x.

Laatikainen L, Erkkila H: Refractive errors and other ocular findings in school children. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1980, 58 (1): 129-136.

O'Donoghue L, McClelland JF, Logan NS, Rudnicka AR, Owen CG, Saunders KJ: Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in Northern Ireland. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010, 94 (9): 1155-1159. 10.1136/bjo.2009.176040.

Logan NS, Shah P, Rudnicka AR, Gilmartin B, Owen CG: Childhood ethnic differences in ametropia and ocular biometry: the Aston Eye Study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2011, 31 (5): 550-558. 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00862.x.

Naidoo KS, Raghunandan A, Mashige KP, Govender P, Holden BA, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB: Refractive error and visual impairment in African children in South Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003, 44 (9): 3764-3770. 10.1167/iovs.03-0283.

Maul E, Barroso S, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein LB: Refractive Error Study in Children: results from La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000, 129 (4): 445-454. 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00454-7.

Czepita D, Mojsa A, Zejmo M: Prevalence of myopia and hyperopia among urban and rural schoolchildren in Poland. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2008, 54 (1): 17-21.

Kleinstein RN, Jones LA, Hullett S, Kwon S, Lee RJ, Friedman NE, Manny RE, Mutti DO, Yu JA, Zadnik K, et al: Refractive error and ethnicity in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003, 121 (8): 1141-1147. 10.1001/archopht.121.8.1141.

Zadnik K, Manny RE, Yu JA, Mitchell GL, Cotter SA, Quiralte JC, et al: Ocular component data in schoolchildren as a function of age and gender. Optom Vis Sci. 2003, 80 (3): 226-36. 10.1097/00006324-200303000-00012.

Dandona R, Dandona L, Naduvilath TJ, Srinivas M, McCarty CA, Rao GN: Refractive errors in an urban population in Southern India: the Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999, 40 (12): 2810-2818.

Shrestha GS, Sujakhu D, Joshi P: Refractive error among school children in Jhapa, Nepal. J Optom. 2011, 4 (2): 49-55. 10.1016/S1888-4296(11)70041-3.

Czepita D, Mojsa A, Ustianowska M, Czepita M, Lachowicz E: Prevalence of refractive errors in schoolchildren ranging from 6 to 18 years of age. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2007, 53 (1): 53-56.

Villarreal GM, Ohlsson J, Cavazos H, Abrahamsson M, Mohamed JH: Prevalence of myopia among 12- to 13-year-old schoolchildren in northern Mexico. Optom Vis Sci. 2003, 80 (5): 369-373. 10.1097/00006324-200305000-00011.

Villarreal MG, Ohlsson J, Abrahamsson M, Sjostrom A, Sjostrand J: Myopisation: the refractive tendency in teenagers. Prevalence of myopia among young teenagers in Sweden. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000, 78 (2): 177-181. 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078002177.x.

Hashemi H, Fotouhi A, Mohammad K: The age- and gender-specific prevalences of refractive errors in Tehran: the Tehran Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2004, 11 (3): 213-225. 10.1080/09286580490514513.

Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M, Giridhar P, McCarty CA, Rao GN: Population-based assessment of refractive error in India: the Andhra Pradesh eye disease study. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2002, 30 (2): 84-93. 10.1046/j.1442-6404.2002.00492.x.

Niroula DR, Saha CG: Study on the refractive errors of school going children of Pokhara city in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2009, 7 (25): 67-72.

Neyeloff J, Fuchs S, Moreira L: Meta-analysis and Forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Research Notes. 2012, 5 (52): doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-52

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6 (7): e1000097-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker B, Sipe T, Thacker S: for the Metha-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Metha-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000, 2008-2012. 283

World Medical Association [WMA] World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Edited by: Association WM. 2004, Tóquio: World Medical Association

Negrel AD, Maul E, Pokharel GP, Zhao J, Ellwein LB: Refractive Error Study in Children: sampling and measurement methods for a multi-country survey. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000, 129 (4): 421-426. 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00455-9.

Giordano L, Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, Ibironke J, Hawes P, Tielsch JM: Prevalence of refractive error among preschool children in an urban population: the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009, 116 (4): 739-746. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.030. 746 e731-734

Larsen JS: The sagittal growth of the eye. IV. Ultrasonic measurement of the axial length of the eye from birth to puberty. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1971, 49 (6): 873-886.

Varma R, Abbot LV, Ayala G, Azen SP, Barak T, Borchert M, Chang J, Chen FK, Chon R, Cotter S, Cuestas C, Deneem J, Diaz J, DiLauro A, Donofrio J, Dozal C, Dzekov J, Foong AW, Gardner J, Garriot R, Lastra C, Lau J, Lin J, Martinez G, Milo K, McKean-Cowdin R, Moya C, Paz S, Penate A, Reiner A, et al: Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Prevalence of myopia and hyperopia in 6- to 72-month-old African American and Hispanic children: the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009, 117 (1): 140-147. e143

Dirani M, Chan YH, Gazzard G, Hornbeak DM, Leo SW, Selvaraj P, Zhou B, Young TL, Mitchell P, Varma R, et al: Prevalence of refractive error in Singaporean Chinese children: the strabismus, amblyopia, and refractive error in young Singaporean Children (STARS) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010, 51 (3): 1348-1355. 10.1167/iovs.09-3587.

Lin LL, Shih YF, Tsai CB, Chen CJ, Lee LA, Hung PT, Hou PK: Epidemiologic study of ocular refraction among schoolchildren in Taiwan in 1995. Optom Vis Sci. 1999, 76 (5): 275-281. 10.1097/00006324-199905000-00013.

Ip JM, Saw SM, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Kifley A, Wang JJ, Mitchell P: Role of near work in myopia: findings in a sample of Australian school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008, 49 (7): 2903-2910. 10.1167/iovs.07-0804.

Garner LF, Kinnear RF, McKellar M, Klinger J, Hovander MS, Grosvenor T: Refraction and its components in Melanesian schoolchildren in Vanuatu. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1988, 65 (3): 182-189. 10.1097/00006324-198803000-00007.

Borchert MS, Varma R, Cotter SA, Tarczy-Hornoch K, McKean-Cowdin R, Lin JH, Wen G, Azen SP, Torres M, Tielsch JM, Friedman DS, Repka MY, Kaltz J, Ibironke J, Giordano L: Risk factors for hyperopia and myopia in preschool children the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease and Baltimore pediatric eye disease studies. Ophthalmology. 2011, 118 (10): 1966-1973. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.030.

Trivedi RH, Wilson ME: Biometry data from caucasian and african-american cataractous pediatric eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007, 48 (10): 4671-4678. 10.1167/iovs.07-0267.

Manny RE, Fern KD, Zervas HJ, Cline GE, Scott SK, White JM, Pass AF: 1% Cyclopentolate hydrochloride: another look at the time course of cycloplegia using an objective measure of the accommodative response. Optom Vis Sci. 1993, 70 (8): 651-665. 10.1097/00006324-199308000-00013.

Goss DA, Cox VD, Herrin-Lawson GA, Nielsen ED, Dolton WA: Refractive error, axial length, and height as a function of age in young myopes. Optom Vis Sci. 1990, 67 (5): 332-338. 10.1097/00006324-199005000-00006.

Lee KE, Klein BE, Klein R, Quandt Z, Wong TY: Association of age, stature, and education with ocular dimensions in an older white population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009, 127 (1): 88-93. 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.521.

McCarthy CS, Megaw P, Devadas M, Morgan IG: Dopaminergic agents affect the ability of brief periods of normal vision to prevent form-deprivation myopia. Exp Eye Res. 2007, 84 (1): 100-107. 10.1016/j.exer.2006.09.018.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2415/14/163/prepub

Acknowledgements

This systematic review is funded by the Federal Agency for the Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) of the Brazilian Ministry of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

VDC and AGF planned the study, conducted the data analysis and wrote the paper. MLVC and MAPV contributed to the planning of the study and revising of the paper. RDM conducted the data analysis and revising of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Castagno, V.D., Fassa, A.G., Carret, M.L.V. et al. Hyperopia: a meta-analysis of prevalence and a review of associated factors among school-aged children. BMC Ophthalmol 14, 163 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2415-14-163

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2415-14-163