Abstract

Background

The standard treatment for non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer (stages T2–T4a) is radical cystectomy with lymphadenectomy. However, patients undergoing cystectomy show metastatic spread in 25% of cases and these patients will have limited benefit from surgery. Identification of patients with high risk of lymph node metastasis will help select patients that may benefit from neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy.

Methods

RNA was procured by laser micro dissection of primary bladder tumors and corresponding lymph node metastases for Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 Gene Chip expression profiling. A publically available dataset was used for identification of the best candidate markers, and these were validated using immunohistochemistry in an independent patient cohort of 368 patients.

Results

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis showed significant enrichment for e.g. metastatic signatures in the metastasizing tumors, and a set of 12 genes significantly associated with lymph node metastasis was identified. Tumors did not cluster according to their metastatic ability when analyzing gene expression profiles using hierarchical cluster analysis. However, half (6/12) of the primary tumor clustered together with matching lymph node metastases, indicating a large degree of intra-patient similarity in these patients. Immunohistochemical analysis of 368 tumors from cystectomized patients showed high expression of GEM (P = 0.033; HR = 1.46) and EDNRA (P = 0.046; HR = 1.60) was significantly associated with decreased cancer-specific survival.

Conclusions

GEM and EDNRA were identified as promising prognostic markers for patients with advanced bladder cancer. The clinical relevance of GEM and EDNRA should be evaluated in independent prospective studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bladder cancer is the 4th most common cancer in men and the 11th most common cancer in women [1]. Patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) are predominantly treated with transurethral resection of the bladder in combination with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) or Mitomycin C. Cystectomy is offered if local control cannot be maintained. Recently, treatment of NMIBC has shifted towards a more aggressive approach based on EORTC risk scores, resulting in more patients receiving cystectomy [2, 3]. The standard treatment for non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) (stages T2–T4a) is radical cystectomy with lymphadenectomy [4]. Patients with immobile tumors (T4b) receive chemotherapy– sometimes followed by salvage cystectomy or radiotherapy [5]. Five-year cancer-specific survival for patients with MIBC is 65% following cystectomy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy increases the 5-year survival with 6–8% but is, for now, not standard treatment in all clinical settings [6, 7].

Patients undergoing cystectomy show metastatic spread in 25% of cases [8], and these patients will have limited benefit of surgery. Identification of patients with high risk of lymph node metastasis could help identify patients that would benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Therefore, identification of metastatic disease (to lymph nodes or distant organs) prior to cystectomy is of high importance. Previously, several studies have focused on studying molecular markers to identify metastatic risk or ability based on analysis of the patient’s primary tumor. Key players in the DNA-damage-response and cell-cycle machinery (e.g. p53, Rb, p21, p16, Tip60) have been investigated by immunohistochemistry, but none of the markers have shown significant power in validation studies to reach the clinic [9–12]. More recently, gene-expression signatures have revealed promising results but have not yet been validated in prospective patient cohorts [13, 14]. Smith et al. reported a 20 gene signature in the primary tumor for predicting lymph node metastasis based on three different cohorts, making it the first study in MIBC where the gene signature was validated in an independent patient cohort [15]. Patients with high relative risk (1.74) and low relative risk (0.70) of node positive disease could be identified. In other disease like e.g. breast cancer, metastatic capacity of the primary tumors has been studied intensely, and several gene expression signatures for predicting metastatic outcome have been develop and successfully validated [16–19].

Here we laser micro dissected primary bladder tumors and corresponding lymph node metastases and performed microarray gene expression profiling of the procured cells. We compared gene expression patterns in primary bladder tumors with and without metastatic disease and by including previously published data from Riester et al.[20] we identified a panel of 12 transcripts significantly associated with disease outcome. The prognostic value of GEM (GTP binding protein overexpressed in skeletal muscle) and EDNRA (endothelin receptor type A) were successfully validated in an independent patient cohort using tissue microarrays (TMAs).

Methods

Patients and follow-up

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the Central Denmark Region Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics (1994/2920). All patients were cystectomized at Department of Urology at Aarhus University Hospital between 1998 and 2008, and surviving patients had at least 36 months of follow-up, and were censored after a maximum of 96 months. Tumor stage was determined using the American Joint Committee on Cancer recommendations from 2002 and WHO 2004 classification was used to determine tumor grade. All patients were clinically free of metastasis before surgery and no patients received neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment in terms of chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Laser micro dissection, RNA extraction and microarray analysis

All patient specimens collected at the time of surgery were split into tissue for pathology and tissue for the biobank. Tissue for the biobank was embedded in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T™ Compound and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at -80°C. Sections were examined by a genitourinary pathologist to identify carcinoma cell content. Following, cresyl violet stained tissue was microdissected using the PALM laser microbeam system. RNA extraction was performed using RNeasy Micro Kits (Qiagen) according to manufacturer protocols. RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (RIN: 2.4-8.8; median 5.9). Total RNA was amplified and converted to cDNA using Nugen Pico-RNA system. The two-round amplification kit is optimized to amplify low volumes and poor quality RNA for Affymetrix array analysis. After amplification, the cDNA was fragmented and labeled using NuGen FL-Ovation kit, loaded onto the Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 Gene Chip according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and scanned using the Affymetrix 3000 7G Scanner.

Microarray data analysis

Raw microarray data was normalized and intensity measures generated by RMA [21] using GeneSpring version 11 software. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of all transcripts with a variance above 1.5 was performed using Cluster 3.0 and Java tree-view software [22]. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) v2.07 software was used to test if previously published gene signatures and curated pathways were enriched in the data. We used the inbuilt KEGG, BIOCARTA, REACTOME, gene ontology, and oncogenic signatures in MsigDB database and supplemented with curated signatures containing “cancer”, “metastasis”, “cell cycle”, “repair”, “DNA damage”, and “hypoxia”. We used the default significance levels to test if significant enrichment was reached with normalized p-values below 0.05 and with false discovery rates below 0.25. A previously published dataset (GEO ID: GSE31684; U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip) from laser microdissected tumors from 93 cystectomized patients was retrieved. A total of 69 patients were included in the analysis, after exclusion of all patients without reported lymph node status, and all node negative patients without 24 months of follow-up.

Tissue microarray (TMA) analysis

Biopsies from a total of 368 tumors from cystectomy specimens and from 41 lymph node metastases were incorporated into a TMA. All tumors were reevaluated regarding T-stage and grade by the same uro-pathologist prior to placement on the TMA. The patients included and the TMA construction is described earlier [11].

Immunohistochemistry and Western blotting

The immunohistochemichal staining procedure was carried out based on the EnVision + TM System HRP (Dako) as previously described [23]. Antibodies against GEM (Novus Biologicals # NBP1-58906) diluted 1:150 and against EDNRA (Abcam #ab76259) diluted 1:800 were used. The specificity of the antibodies against GEM and EDNRA was validated by Western blotting using T24 cell line essentially as described earlier [24].

Scoring of IHC staining

A Hamamatsu Nanozoomer scanner (Hamamatsu Corporation, Hamamatsu City, Japan) was used to scan the TMA slides, and VIS visualization software (Visiopharm A/S, Hørsholm, Denmark) was used for visualization of IHC staining during scoring of the protein expression intensities. Percentage of positive carcinoma cells was scored on a continuous scale for each core, and optimal cut-off values were afterwards defined by ROC curves. Scoring was performed by two observers blinded to outcome. The first observer scored on a continuous scale, and the second scored according to the dichotomized cutoff value generated. Differences in the dichotomized scorings were reviewed and consensus was reached.

Statistics

Comparisons between the metastatic and non-metastatic groups were performed using two-sided t-test statistics. Categorical data was compared in univariate analysis using the χ2 test and censored data was compared using log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HR) were estimated using Cox proportional hazard models. Multivariate analysis was performed separately for each biomarker including only significant clinical parameter from the univariate analysis. All analyses were performed using STATA (version 11).

Results

For gene expression profiling we selected 18 primary tumors and 12 matched lymph node metastases from 18 patients with bladder cancer. Ten patients had at least one lymph node metastasis at time of cystectomy, and 6 patients died of bladder cancer. Clinical and histopathological information for each patient is listed in Table 1.

Molecular subgroup analysis

Initially, data was filtered, selecting only transcripts with a variance above 1.5 across all samples (11046 transcripts). We performed unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis to investigate if tumors clustered based on stage or metastatic abilities, and if lymph nodes showed a high degree of similarity to the matched primary tumors (Figure 1). Cluster analysis separated the tumors into two main clusters; one cluster (cluster A) contained seven primary metastasizing tumors, three primary non-metastasizing tumors, and eight lymph nodes, and among these were six of the seven matched pairs. The other cluster (cluster B) contained five primary non-metastasizing tumors, five metastasizing primary tumors, and four lymph nodes. Seven of the lymph nodes clustered together with their matched primary tumor, indicating a large degree of intra-patient similarity in these patients. However, the overall expression patterns did not show significant separation of the tumors based on metastatic ability. Most of the muscle-invasive tumors clustered together in cluster A – as expected.

Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of all samples. Square brackets are used when the coupled tumor and metastasis cluster together. Green color represents a primary non-metastasizing tumor. Dark green represents a primary non-metastasizing tumor which later develops lymph node metastases in the abdomen. Blue color represents a primary metastasizing tumor. Red color represents a lymph node metastasis.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

To investigate the differences between the metastatic and non-metastatic tumors more specifically, we applied GSEA for investigating enrichment for previously published signatures regarding key elements in the metastatic process together with enrichment for pathway elements (Table 2). Interestingly, all signatures regarding extracellular function, metastasis, hypoxia, proliferation, and survival were exclusively enriched in metastatic tumors while all signatures regarding repair and cell cycle were enriched in non-metastatic tumors. Cell signaling was primarily enriched in metastatic tumors while metabolism was primarily enriched in non-metastatic tumors. In addition, we investigated enrichment for previously published signatures comparing primary tumors and metastasis [25–27]; both signatures containing tumors from many different tissues were significantly enriched in our dataset (Ramaswamy et al., P = 0.02 and Daves et al., P = 0.03), while the signature from metastatic malignant melanoma was borderline significantly enriched (Daves et al., P = 0.06).

Matched-pair analysis

We used the paired tumors and lymph node metastases to investigate the intra- and inter-patient similarity. When comparing differences in transcript levels between the matched primary tumors and metastases using two-fold difference as cut-off, we did not find any transcripts that were differentially expressed in all 12 tumor-lymph node comparisons (Figure 2). MMP2 was the only gene that was down-regulated in 11 lymph node metastases, while 18 transcripts were up or down regulated in 10 lymph node metastases. In general, as observed in the cluster analysis, the patients show a large heterogeneity in expression patterns between primary tumors and lymph node metastases. Using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis we did not identify any general pathway changes between primary tumors and lymph node metastases, probably because of this large heterogeneity observed between patients.

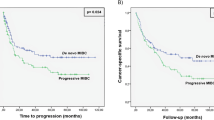

Identification of markers associated with outcome

Because of the large heterogeneity observed and because of the limited sample size we included a previously published dataset for delineation of markers associated with outcome (GEO ID: GSE31684). The dataset contained Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip data from 69 patients with known lymph node status and at least 24 months of follow-up if no lymph node metastasis was present at surgery. Separately, for both datasets, we delineated transcripts associated with the presence or absence of metastasis; only transcripts with a mean fold change difference > 2 and with a P < 0.05 (student’s t-test) were selected. Twelve transcripts up-regulated in metastasizing tumors passed our selection criteria in both datasets (Table 3). We selected EDNRA and GEM (Figure 3) for further validation using immunohistochemistry (IHC). For this we used a tissue microarray containing 409 core biopsies from both primary tumors (n = 368) and lymph node metastases (n = 41). Both GEM and EDNRA protein expression was localized in the cytoplasm of the cells, and no staining was observed in normal urothelium or connective tissue cells. IHC scoring was performed by two observers independently, with an inter-observer agreement of 0.70 (GEM) and of 0.81 (EDNRA), using Cohen’s kappa. The clinical and histopathological characteristics for the patients included in this cohort are listed in Table 4. High expression of GEM (P = 0.033; HR = 1.46) and EDNRA (P = 0.046; HR = 1.60) were significantly associated with decreased cancer-specific survival (Figure 4). Furthermore, after performing multivariate analysis high EDRNA expression showed significantly association with decreased cancer-specific survival (P = 0.046), while GEM showed no significance (P = 0.11). Finally we investigated the similarity in protein expression between matched primary tumors and lymph node metastases; 94% of the lymph nodes showed similar expression as in the primary tumors for EDNRA and 71% for GEM.

Discussion

The risk of recurrence and later metastasis following cystectomy is as high as 50% [28] and most patients will ultimately succumb to the disease following recurrence [29]. Therefore, early detection of metastasis and prediction of recurrence risk following cystectomy could ultimately improve survival as better treatment regimens could be applied. The aim of this study was to identify markers of lymph node metastasis at (before) cystectomy. We compared gene-expression profiles from 10 primary bladder tumors with 12 matched lymph node metastases and eight primary tumors without metastasis to identify markers associated with metastatic disease, and to test similarity between lymph node metastases and matched primary tumors. Overall, we found no large difference in gene expression between the two patient groups. Furthermore, we found that primary tumors and corresponding lymph node metastases showed comparable gene expression profiles in half of the cases. The reason for this lack of overall difference between the groups may be caused by tumor heterogeneity, minor sub clones responsible for metastatic ability, and also by inclusion of tumors of different stages (T1-T4). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to investigate biological differences between metastasizing and non-metastasizing tumors. Interestingly, signatures associated with “metastasis”, “extracellular function”, “proliferation and survival”, and “cell signaling” were significantly enriched in the metastasizing tumors while signatures associated with “metabolism”, “cell cycle” and “DNA repair” were associated with non-metastatic tumors – indicating that the overall biological process may be different in the two tumor groups. However, due to the large heterogeneity we were not able to identify general molecular differences between lymph node metastases and primary tumors.

The tumor heterogeneity (intra and inter) may make marker identification difficult, and consequently we included additional patient samples from a previously published dataset [20] for delineating significant markers of outcome. The panel of 12 genes that were significant in both datasets contained GEM and EDNRA. These genes were selected for further validation based on significance, difference in expression, expression level, and based on antibody availability. We found no overlap between our 12 genes and the 21-gene metastasis signature reported by Smith et al. previously [15], which may reflects multiple factors like cohort heterogeneity and size, and differences in sampling (laser micro dissection vs bulk tumor analysis). We found high expression of GEM and EDNRA to be significantly associated with a decrease in cancer-specific survival, when analyzing the protein expression on a cohort of 368 patients. Furthermore, high EDNRA was significantly associated with decreased cancer-specific survival in multivariate analysis.

The possible functional roles of EDNRA (endothelin receptor type A) and GEM (GTP binding protein overexpressed in skeletal muscle) in cancer progression and metastasis are currently unclear. EDNRA and GEM have not been associated with disease outcome and cancer outcome. GEM is a small GTP-binding protein that plays a role in regulating Ca2+ channel expression at the cell surface [30]. Furthermore, it is involved in cytoskeletal remodeling in interphase cells and is a spindle-associated protein required for prober mitotic progression [31]. EDNRA is a G-protein coupled receptor for endothelins and it is expressed on vascular smooth-muscle cells and on heart, kidney, and neuronal cells [32].

This study included a limited number of tumors in the initial characterization of tumor subgroups, and although we isolated carcinoma cells in primary tumors and lymph node metastases using laser-micro dissection, the patient cohort may still be too small to draw firm conclusion regarding molecular subgroups and differences between primary tumors and metastatic lesions. The strength of our approach is the inclusion of matched lymph node metastasis in the selection of candidate markers for metastasis, and this is to our knowledge the first study of bladder cancer that compare the lymph nodes to the primary tumors.

Recently, large intra-tumor heterogeneity of several cancer types has been reported [33–35]. A recent study of clear cell renal cell carcinomas showed significant molecular heterogeneity using whole-exome sequencing of multiple tumor areas [36]. As small cellular sub-clones may be responsible for the disease progression and metastasis it may be difficult to identify any good molecular markers of outcome by analyzing the bulk tumors. Other studies of tumor metastasis in mice have shown limited overlap in genomic alterations (about 9%) between primary tumors and metastases [37], indicating that metastatic lesions probably propagate from small sub-populations in the primary tumors. Intra-tumor heterogeneity has so far not been addressed in detail in bladder cancer. However, Li et al.[38] performed whole-exome sequencing of 66 individual cells from a single muscle invasive tumor, and identified large variation in mutant genes between the cells. Other groups [39, 40] have recently shown that muscle invasive bladder cancers belong to 4–5 distinct molecular subgroups. Consequently, future studies of prognostic markers for patients with advanced bladder cancer should include large patient cohorts, stratification according to overall tumor subgroup and sub-clonal analysis to compensate for the large inter and intra tumor heterogeneity for these patients.

Conclusion

We observed a high degree of heterogeneity between primary tumors with and without metastases, and between paired samples of primary tumors and associated lymph-node metastases. GEM and EDNRA were identified to be promising prognostic markers for patients with advanced bladder cancer. The clinical relevance of GEM and EDNRA should be evaluated in independent prospective studies.

References

Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E: Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010, 60 (5): 277-300. 10.3322/caac.20073.

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, Kaasinen E, Bohle A, Palou-Redorta J, Roupret M: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the 2011 update. Eur Urol. 2011, 59 (6): 997-1008. 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.017.

Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, Witjes JA, Bouffioux C, Denis L, Newling DW, Kurth K: Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006, 49 (3): 466-477. 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031.

Stenzl A, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Kuczyk MA, Merseburger AS, Ribal MJ, Sherif A, Witjes JA: Treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: update of the EAU guidelines. Eur Urol. 2011, 59 (6): 1009-1018. 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.023.

Kaufman E, Fried M: Polypoid lesions following surgical correction of bladder exstrophy. Endoscopy. 2009, 41 Suppl 2: E323-

Griffiths G, Hall R, Sylvester R, Raghavan D, Parmar MK: International phase III trial assessing neoadjuvant cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: long-term results of the BA06 30894 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29 (16): 2171-2177.

Sherif A, Holmberg L, Rintala E, Mestad O, Nilsson J, Nilsson S, Malmstrom PU: Neoadjuvant cisplatinum based combination chemotherapy in patients with invasive bladder cancer: a combined analysis of two Nordic studies. Eur Urol. 2004, 45 (3): 297-303. 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.09.019.

Jensen JB, Ulhoi BP, Jensen KM: Evaluation of different lymph node (LN) variables as prognostic markers in patients undergoing radical cystectomy and extended LN dissection to the level of the inferior mesenteric artery. BJU Int. 2012, 109 (3): 388-393. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10369.x.

Matsushita K, Cha EK, Matsumoto K, Baba S, Chromecki TF, Fajkovic H, Sun M, Karakiewicz PI, Scherr DS, Shariat SF: Immunohistochemical biomarkers for bladder cancer prognosis. Int J Urol. 2011, 18 (9): 616-629.

Laurberg JR, Brems-Eskildsen AS, Nordentoft I, Fristrup N, Schepeler T, Ulhoi BP, Agerbaek M, Hartmann A, Bertz S, Wittlinger M, Fietkau R, Rödel C, Borre M, Jensen JB, Orntoft T, Dyrskjøt L: Expression of TIP60 (tat-interactive protein) and MRE11 (meiotic recombination 11 homolog) predict treatment-specific outcome of localised invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2012, 110 (11): E1228-E1236.

Jensen JB, Munksgaard PP, Sorensen CM, Fristrup N, Birkenkamp-Demtroder K, Ulhoi BP, Jensen KM, Orntoft TF, Dyrskjot L: High expression of karyopherin-alpha2 defines poor prognosis in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer and in patients with invasive bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Eur Urol. 2011, 59 (5): 841-848. 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.048.

Shariat SF, Tokunaga H, Zhou J, Kim J, Ayala GE, Benedict WF, Lerner SP: p53, p21, pRB, and p16 expression predict clinical outcome in cystectomy with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22 (6): 1014-1024. 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.118.

Blaveri E, Simko JP, Korkola JE, Brewer JL, Baehner F, Mehta K, Devries S, Koppie T, Pejavar S, Carroll P, Waldman FM: Bladder cancer outcome and subtype classification by gene expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 11 (11): 4044-4055. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2409.

Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Lozano J, Saint F, Cordon-Cardo C: Defining molecular profiles of poor outcome in patients with invasive bladder cancer using oligonucleotide microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24 (5): 778-789. 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2375.

Smith SC, Baras AS, Dancik G, Ru Y, Ding KF, Moskaluk CA, Fradet Y, Lehmann J, Stöckle M, Hartmann A, Lee JK, Theodorescu D: A 20-gene model for molecular nodal staging of bladder cancer: development and prospective assessment. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12 (2): 137-143. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70296-5.

Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lønning PE, Børresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D: Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000, 406 (6797): 747-752. 10.1038/35021093.

Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Lønning PE, Børresen-Dale AL: Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001, 98 (19): 10869-10874. 10.1073/pnas.191367098.

van't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, Peterse HL, van der Kooy K, Marton MJ, Witteveen AT, Schreiber GJ, Kerkhoven RM, Roberts C, Linsley PS, Bernards R, Friend SH: Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002, 415 (6871): 530-536. 10.1038/415530a.

Ellis MJ, Suman VJ, Hoog J, Lin L, Snider J, Prat A, Parker JS, Luo J, DeSchryver K, Allred DC, Esserman LJ, Unzeitig GW, Margenthaler J, Babiera GV, Marcom PK, Guenther JM, Watson MA, Leitch M, Hunt K, Olson JA: Randomized phase II neoadjuvant comparison between letrozole, anastrozole, and exemestane for postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-rich stage 2 to 3 breast cancer: clinical and biomarker outcomes and predictive value of the baseline PAM50-based intrinsic subtype--ACOSOG Z103. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29 (17): 2342-2349. 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.6950.

Riester M, Taylor JM, Feifer A, Koppie T, Rosenberg JE, Downey RJ, Bochner BH, Michor F: Combination of a novel gene expression signature with a clinical nomogram improves the prediction of survival in high-risk bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012, 18 (5): 1323-1333. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2271.

Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP: Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003, 4 (2): 249-264. 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249.

Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D: Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998, 95 (25): 14863-14868. 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863.

Heeboll S, Borre M, Ottosen PD, Andersen CL, Mansilla F, Dyrskjot L, Orntoft TF, Torring N: SMARCC1 expression is upregulated in prostate cancer and positively correlated with tumour recurrence and dedifferentiation. Histol Histopathol. 2008, 23 (9): 1069-1076.

Schepeler T, Mansilla F, Christensen LL, Orntoft TF, Andersen CL: Clusterin expression can be modulated by changes in TCF1-mediated Wnt signaling. J Mol Signal. 2007, 2: 6-10.1186/1750-2187-2-6.

Daves MH, Hilsenbeck SG, Lau CC, Man TK: Meta-analysis of multiple microarray datasets reveals a common gene signature of metastasis in solid tumors. BMC Med Genomics. 2011, 4: 56-10.1186/1755-8794-4-56.

Ramaswamy S, Ross KN, Lander ES, Golub TR: A molecular signature of metastasis in primary solid tumors. Nat Genet. 2003, 33 (1): 49-54.

Jaeger J, Koczan D, Thiesen HJ, Ibrahim SM, Gross G, Spang R, Kunz M: Gene expression signatures for tumor progression, tumor subtype, and tumor thickness in laser-microdissected melanoma tissues. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 13 (3): 806-815. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1820.

Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, Palapattu GS, Lotan Y, Rogers CG, Amiel GE, Vazina A, Gupta A, Bastian PJ, Sagalowsky AI, Schoenberg MP, Lerner SP: Outcomes of radical cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a contemporary series from the Bladder Cancer Research Consortium. J Urol. 2006, 176 (6 Pt 1): 2414-2422. discussion 2422

Rink M, Lee DJ, Kent M, Xylinas E, Fritsche HM, Babjuk M, Brisuda A, Hansen J, Green DA, Aziz A, Cha EK, Novara G, Chun FK, Lotan Y, Bastian PJ, Tilki D, Gontero P, Pycha A, Baniel J, Mano R, Ficarra V, Trinh QD, Tagawa ST, Karakiewicz PI, Scherr DS, Sjoberg DD, Shariat SF, Bladder Cancer Research Consortium: Predictors of cancer-specific mortality after disease recurrence following radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2013, 111 (3 Pt B): E30-E36.

Beguin P, Nagashima K, Gonoi T, Shibasaki T, Takahashi K, Kashima Y, Ozaki N, Geering K, Iwanaga T, Seino S: Regulation of Ca2+ channel expression at the cell surface by the small G-protein kir/Gem. Nature. 2001, 411 (6838): 701-706. 10.1038/35079621.

Andrieu G, Quaranta M, Leprince C, Hatzoglou A: The GTPase Gem and its partner Kif9 are required for chromosome alignment, spindle length control, and mitotic progression. FASEB J. 2012, 26 (12): 5025-5034. 10.1096/fj.12-209460.

Yu JC, Pickard JD, Davenport AP: Endothelin ETA receptor expression in human cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1995, 116 (5): 2441-2446. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15093.x.

Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, Tarpey P, Varela I, Phillimore B, Begum S, McDonald NQ, Butler A, Jones D, Raine K, Latimer C, Santos CR, Nohadani M, Eklund AC, Spencer-Dene B, Clark G, Pickering L, Stamp G, Gore M, Szallasi Z, Downward J, Futreal PA, Swanton C: Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012, 366 (10): 883-892. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205.

Lohr JG, Stojanov P, Carter SL, Cruz-Gordillo P, Lawrence MS, Auclair D, Sougnez C, Knoechel B, Gould J, Saksena G, Cibulskis K, McKenna A, Chapman MA, Straussman R, Levy J, Perkins LM, Keats JJ, Schumacher SE, Rosenberg M, Multiple Myeloma Research C, Getz G, Golub TR: Widespread genetic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer Cell. 2014, 25 (1): 91-101. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.015.

Shah SP, Roth A, Goya R, Oloumi A, Ha G, Zhao Y, Turashvili G, Ding J, Tse K, Haffari G, Bashashati A, Prentice LM, Khattra J, Burleigh A, Yap D, Bernard V, McPherson A, Shumansky K, Crisan A, Giuliany R, Heravi-Moussavi A, Rosner J, Lai D, Birol I, Varhol R, Tam A, Dhalla N, Zeng T, Ma K, Chan SK, et al: The clonal and mutational evolution spectrum of primary triple-negative breast cancers. Nature. 2012, 486 (7403): 395-399.

Gerlinger M, Horswell S, Larkin J, Rowan AJ, Salm MP, Varela I, Fisher R, McGranahan N, Matthews N, Santos CR, Martinez P, Phillimore B, Begum S, Rabinowitz A, Spencer-Dene B, Gulati S, Bates PA, Stamp G, Pickering L, Gore M, Nicol DL, Hazell S, Futreal PA, Stewart A, Swanton C: Genomic architecture and evolution of clear cell renal cell carcinomas defined by multiregion sequencing. Nat Genet. 2014, 46 (3): 225-233. 10.1038/ng.2891.

Wu X, Northcott PA, Dubuc A, Dupuy AJ, Shih DJ, Witt H, Croul S, Bouffet E, Fults DW, Eberhart CG, Garzia L, Van Meter T, Zagzag D, Jabado N, Schwartzentruber J, Majewski J, Scheetz TE, Pfister SM, Korshunov A, Li XN, Scherer SW, Cho YJ, Akagi K, MacDonald TJ, Koster J, McCabe MG, Sarver AL, Collins VP, Weiss WA, Largaespada DA, et al: Clonal selection drives genetic divergence of metastatic medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012, 482 (7386): 529-533. 10.1038/nature10825.

Li Y, Xu X, Song L, Hou Y, Li Z, Tsang S, Li F, Im KM, Wu K, Wu H, Ye X, Li G, Wang L, Zhang B, Liang J, Xie W, Wu R, Jiang H, Liu X, Yu C, Zheng H, Jian M, Nie L, Wan L, Shi M, Sun X, Tang A, Guo G, Gui Y, Cai Z, et al: Single-cell sequencing analysis characterizes common and cell-lineage-specific mutations in a muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Gigascience. 2012, 1 (1): 12-10.1186/2047-217X-1-12.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research N: Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014, 507 (7492): 315-322. 10.1038/nature12965.

Sjödahl G, Lauss M, Lövgren K, Chebil G, Gudjonsson S, Veerla S, Patschan O, Aine M, Fernö M, Ringnér M, Månsson W, Liedberg F, Lindgren D, Höglund M: A molecular taxonomy for urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012, 18 (12): 3377-3386. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0077-T.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/14/638/prepub

Acknowledgements

The work was also supported The John and Birthe Meyer Foundation; the Danish Cancer Society; the Ministry of Technology and Science; The Danish Cancer Biobank (DCB) and the Lundbeck Foundation. Furthermore, our research has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework program FP7/2007-2011 under grant agreement n° 201663. We thank Ms. Pamela Celis, Ms. Margaret Gellett, and Ms. Hanne Steen for excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JRL, JBJ, TFØ and LD designed the study; MB and JBJ provide tumor tissue and clinical data; JRL, JBJ and TS performed the laboratory research; JRL, TS and LD analyzed data; JRL and LD wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Laurberg, J.R., Jensen, J.B., Schepeler, T. et al. High expression of GEM and EDNRA is associated with metastasis and poor outcome in patients with advanced bladder cancer. BMC Cancer 14, 638 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-638

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-638