Abstract

Background

Several conservative (i.e., nonpharmacologic, nonsurgical) treatments exist for secondary lymphedema. The optimal treatment is unknown. We examined the effectiveness of conservative treatments for secondary lymphedema, as well as harms related to these treatments.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE®, EMBASE®, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials®, AMED, and CINAHL from 1990 to January 19, 2010. We obtained English- and non-English-language randomized controlled trials or observational studies (with comparison groups) that reported primary effectiveness data on conservative treatments for secondary lymphedema. For English-language studies, we extracted data in tabular form and summarized the tables descriptively. For non-English-language studies, we summarized the results descriptively and discussed similarities with the English-language studies.

Results

Thirty-six English-language and eight non-English-language studies were included in the review. Most of these studies involved upper-limb lymphedema secondary to breast cancer. Despite lymphedema's chronicity, lengths of follow-up in most studies were under 6 months. Many trial reports contained inadequate descriptions of randomization, blinding, and methods to assess harms. Most observational studies did not control for confounding. Many studies showed that active treatments reduced the size of lymphatic limbs, although extensive between-study heterogeneity in areas such as treatment comparisons and protocols, and outcome measures, prevented us from assessing whether any one treatment was superior. This heterogeneity also precluded us from statistically pooling results. Harms were rare (< 1% incidence) and mostly minor (e.g., headache, arm pain).

Conclusions

The literature contains no evidence to suggest the most effective treatment for secondary lymphedema. Harms are few and unlikely to cause major clinical problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Secondary lymphedema (SE) is an acquired condition resulting from disease, trauma, or an iatrogenic process such as surgery or radiation that damages the lymphatic system [1, 2]. Clinically, SE may present as edema [3].

Globally, the major cause of SE is lymphatic filariasis resulting from infection with the nematode Wusheria Bancrofti. In the United States (U.S.), the most common cause of SE is treatment for malignancy (i.e., surgery, radiation) [4], especially breast cancer. SE incidence rates following mastectomy range from 24% to 49%, with lower rates of 4% to 28% following lumpectomy [1]. The literature is bereft of reliable prevalence estimates, although some suggest approximately 10 million persons in the U.S. have SE http://www.shlnews.org/?p=67.

Several types of conservative therapy exist to treat SE. Compression techniques, including multilayer bandaging, and pressure garments are thought to restore hydrostatic pressure and improve lymph flow in affected limbs [5]. Manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), a form of massage, is administered using light strokes to direct lymph flow from blocked to open lymphatics [5–7]. Exercise helps increase lymph flow via muscle contraction around the lymphatics [8]. Complex (or complete) decongestive therapy (CDT) includes MLD, limb compression with low stretch bandages, skin care, and exercise. The intent of CDT is to decrease fluid in affected limbs, prevent infection, and improve tissue integrity [5, 9]. Dieting (e.g., low-fat diet) is also used as a conservative therapy for SE.

Mechanical treatments for SE include intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices and low-level laser therapy (LLLT). IPC devices are pneumatic cuffs connected to pumps that mimic the naturally occurring muscle pump effect of muscles contracting around peripheral lymphatics [10]. LLLT employs low intensity laser waves and appears to encourage formation of lymphatic vessels, promote lymph flow, and stimulate immune systems [11, 12].

This systematic review is based on a peer-reviewed technology report [13] commissioned by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). A copy of the technology report is available on the AHRQ website http://www.cms.gov/determinationprocess/downloads/id66aTA.pdf. The technology report served as background material for a Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) Meeting held in November 2009. One purpose of the meeting was to discuss the available evidence for treatment methods in SE.

This review addresses two key questions:

-

1.

How effective are conservative treatments for SE in pediatric or adult populations who developed SE following any type of illness except filariasis infection?

-

2.

What harms are associated with conservative treatments for SE?

Methods

Data sources and selection

We searched MEDLINE®, EMBASE®, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials®, AMED, and CINAHL from 1990 to January 19, 2010. We exploded the subject heading 'lymphedema' and searched it as a textword ('lymphedema' or 'lymphoedema'). The complete literature search strategy is depicted in Additional file 1 Methods S1. We initially searched the English-language literature and later searched the non-English literature following recommendations of persons who peer reviewed our technology report [13]. The purpose of exploring non-English studies was to assess whether they contained information to supplement the English-language studies. We also searched the reference lists of extracted studies and previously published systematic reviews [1, 12, 14–16].

Criteria for considering studies for this review

We included studies provided they were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational studies with comparison groups (e.g., cohort, case control). We also included studies of pediatric and adult patients who received treatment for SE following any form of illness except filariasis infection. We excluded case series, case reports, narrative and systematic reviews, editorials, comments, letters, opinion pieces, abstracts, conference proceedings, and animal experiments. We also excluded studies involving pharmacologic or surgical treatments for SE.

Trained raters independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the articles retrieved in the literature search. The criteria were applied at three levels of screening: I-title and abstract first review; II-title and abstract second review; III-full text. We extracted data from articles that passed full text screening. Raters managed the screening process electronically using standardized screening forms and Distiller SR systematic review software (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada).

Methodological quality assessment

Two raters independently assessed the quality of the extracted English-language articles. Raters used the eight-point Jadad scale for RCTs [17, 18] and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [19] for observational studies. The overall quality of each extracted article was rated 'good', 'fair', or 'poor' in accordance with the recommendations outlined in the AHRQ's methods guide for systematic reviews [20].

Issues of methodological quality often preclude the inclusion of observational studies in systematic reviews. However, observational studies may be included to help overcome evidence gaps in RCTs, especially in the assessment of harms [20].

Data extraction

A meta analysis was infeasible because the extracted studies exhibited substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Therefore, we used a descriptive approach to answer the key questions. This approach involved extracting English-language data into tables and developing written summaries of the English and non-English evidence.

For English-language articles, we extracted data on study design, type of treatment, sample size, cause of SE, definition of SE, study inclusion/exclusion criteria, and outcome data. While we did not extract data from the non-English articles, we summarized the main contents of these articles in writing and compared them to the extracted English-language articles.

Role of the funding source

The McMaster University Evidence-based Practice Centre researched and wrote the initial technology report under contract with the AHRQ, which gave us permission to publish this manuscript. The AHRQ and CMS had no role in the literature search, data analysis, study conduct, manuscript preparation, or interpretation of results.

Results

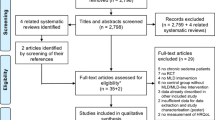

Figure 1 depicts the flow of studies through screening. Thirty-six English-language and eight non-English-language studies passed screening. Table 1 contains basic information on the English-language studies; Table 2 shows extracted English-language data relevant to answering the two key questions listed above.

Methodological quality assessment

Of the 36 English-language studies, 30 were RCTs [11, 21–41, 43–50] and six were observational (cohort) [51–56]. Fifteen RCTs were fair quality [21, 22, 25, 26, 29–32, 36, 43–47, 50], eight were good quality [11, 24, 27, 35, 38, 41, 48, 49], and seven were poor quality [23, 28, 33, 34, 37, 39, 40]. Among the observational studies, three were good quality [52, 54, 55] and three were poor quality [51, 53, 56].

The major quality issues with the RCTs were inadequate description of randomization processes in about half the studies, no reports of double blinding in a majority of the studies, and no discussion of methods to assess harms in most studies.

For the observational studies, the major quality issue was related to confounding. Four of the six studies [52, 54–56] did not report attempts to control confounding. The authors of two studies [51, 53] controlled potential confounding by matching on SE severity.

Summary of extracted studies

Thirty-two of 36 English-language studies included participants with lymphedema secondary to breast cancer [11, 21, 22, 24–32, 34–41, 43–52, 54, 55]. Some studies specified that participants had to be in remission, have no relapse, or have no metastases [21, 22, 24, 26, 29, 35, 41, 43, 44, 46–48]. Five studies defined SE as 'mild' [21, 22], 'chronic' [47], or 'moderate to severe' [24, 48]. Sample sizes ranged from eight [32] to 150 [51].

Intervals between study participants' completion of cancer treatment and recruitment into the extracted studies varied considerably, e.g., 3 to 6 weeks [36], at least 3 months [46], at least 4 months [21, 29], at least 6 months [22, 27], at least 12 months [24, 43, 44], between 1 month and 1 year [47], or at least 4 years [30]. We also found variation in elapsed times between SE symptom onset and study recruitment, e.g., at least 3 months [32, 34], greater than 3 months [50], a median of 9 to 10.5 months [31], less than 1 year [26], less than or equal to 2 years [25], or 0 to 5 years [49].

Follow-up periods varied considerably between studies, with little relation between follow-up length, study type, or intervention. Many studies ended immediately after the treatment regimen, although five studies followed patients for up to 1 year [34, 41, 51, 53, 54]. The shortest study lasted 24 h [24].

Several RCTs did not clearly label treatments as 'comparator' or 'experimental' (e.g., a study of IPC and MLD [31]). For this review, we assumed the comparators were the more conservative therapies. Common conservative therapies in RCTs were "usual care", sham treatment, or no treatment [11, 26, 27, 32, 36, 37, 43, 44, 52]. 'Active' treatment comparators included complex decongestive therapy [28, 46, 47], elastic sleeve [21, 22, 52], self-massage [49], bandaging alone [24, 38], "simple lymphatic drainage" [45, 50], IPC [34], MLD [23, 30], or physiotherapy [33].

In the observational studies, comparators included IPC, compression garment, MLD, or no active treatment [51–56].

Many RCTs measured outcomes using limb volume or circumference [22, 26, 32, 34, 36, 40]. Other outcomes included subjective symptoms such as pain, heaviness, or tension [28, 30–32, 34, 36, 55], range of joint motion (usually shoulder) [11, 21, 29–32, 46], grip strength [31, 34], measurements of intra- and extra-cellular fluid levels through bioimpedance [11, 27], skin-fold thickness [43, 44], and skin tonicity using tonometry [11, 46, 47]. Some studies attempted to correlate results of SE treatment with changes in quality of life [37, 49].

For the observational studies, outcomes included limb volume [51–53, 55, 56], skin firmness [51], subjective assessments of body weight [55], limb circumference [56], and a vaguely described scale of 'psychic well-being' and 'physical complaints' [54].

How effective are conservative treatments for SE in pediatric or adult populations who developed SE following any type of illness except filariasis infection?

Two RCTs showed IPC had benefits over CDT or self-massage [46, 49]. Three other RCTs failed to show superiority of IPC compared to lymphatic massage [31], skin care [26], or elastic sleeve [22]. One RCT showed that a three-chamber IPC sleeve was better at reducing edema than a one-chamber sleeve [39].

Six RCTs used some form of massage-based therapy as the study treatment. Of these, only one suggested benefits in the massage group [25]. Other studies found no differences between massage and bandaging alone [38], elastic sleeve [21], or a less intensive form of massage [45, 50].

In three studies of laser treatment, laser was superior to exercise [36], sham laser [11], or no treatment [35]. In a fourth laser study, laser was beneficial versus sham laser at intermediate time points [not at the endpoint], although the study authors did not provide quantitative statistical comparisons of the intermediate data [32].

Authors reported conflicting dieting results. One study showed no improvement with low fat or low caloric diets [44], while another showed improvement when dietary advice supplemented use of elastic sleeves [44].

Poor quality trials were more likely to suggest treatment benefits in experimental groups. Two RCTs involving IPC reported significantly more reductions in arm circumference when compared to MLD [40] or laser [34]. A study of bone marrow stromal cell transplantation versus decongestive therapy reported greater reductions in excess arm volumes with transplant (i.e., 81% vs. 55%; p < 0.001) [28].

The six observational studies examined a mixed group of treatments and found equivocal results: ultrasound was no different than IPC in reducing arm circumference [51], modified MLD reduced SE volume by 22% relative to standard MLD (authors did not report p-values) [56], group talks and exercise sessions added to MLD and compression stockings improved 'psychic well-being' (p < 0.05) yet made no difference in physical complaints [54], and persons with Kaposi's sarcoma who wore daily compression stockings had reductions in limb volume versus persons who wore no stockings (p < 0.001; authors failed to report the size of the treatment effect) [53]. Persons receiving MLD in addition to compression bandaging experienced less pain than persons receiving bandaging alone (p < 0.03), but the results showed no statistically significant reductions in absolute limb volume (p = 0.07) [55]. The final observational study compared sleeve to IPC and the authors found no significant differences in volume reductions between groups (the authors did not provide quantitative data) [52].

Some studies showed a loss of benefit by the end of the follow-up period. One observational study of elastic sleeve versus IPC found that both groups had returned to baseline levels within 4 to 12 weeks post-treatment [52]. Another study suggested a superior response to laser compared with sham treatment at 3 weeks following the last laser treatment. This benefit was lost after 7 weeks [32].

Considering the chronicity of SE, very few studies had long-term follow-ups. Eight of 36 studies reported outcomes at 6 months or more, with benefits shown to last for up to 1 year in some cases, usually with concomitant use of maintenance therapy (e.g., elastic sleeve).

What harms are associated with conservative treatments for SE?

Harms were sporadically reported in the extracted studies. Only 17 of 30 RCTs reported harms [11, 23–27, 32–34, 36, 38, 43–47, 49]. The majority of harms were related to disease recurrence, not SE.

Some studies mentioned specific harms from therapy. These harms were rare, occurring in less than 1% of patients. Harms included infection, dermatitis [11, 38], arm thrombosis [11, 44], headache with elevated blood pressure [46], and arm pain [38]. None of these harms had major clinical impacts in any of the studies.

Only two studies compared harms between treatments. In an RCT evaluating bandages, subjects getting high-pressure bandages reported more pain and discomfort than subjects getting low pressure bandages, although the harms were measured using an invalidated scale [24]. A similar scale was used in an RCT comparing kinesiology tape with short stretch bandaging: subjects in the kinesiology tape group reported greater wound development than subjects in the bandage group (p = 0.013) [48].

No studies reported on factors that may increase the risk of harms associated with treatment.

Non english-language studies

We included eight non-English-language studies. All eight studies were observational and involved breast cancer survivors with upper limb SE. Sample sizes ranged from 30 [57, 58] to 440 [59]. Lengths of follow-up, where reported, ranged from 28 days [57] to 10 years [59].

Three studies examined single modality treatments: self-administered MLD versus an unspecified comparator, with improved arm function in the MLD group [60]; MLD delivered via the 'Asdonk standard' method versus 'non-Asdonk MLD', with greater reductions in arm volume in the Asdonk group (the authors described the Asdonk method, but did not reference the method, nor did they provide quantitative statistics or p-values) [57]; and single- versus multi-chamber IPC, with no differences in SE severity between groups at the end of follow-up [61].

Three studies investigated multi-modal treatments: multi-layer bandaging and MLD versus simplified bandaging and MLD, with larger decreases in edema occurring in the simplified bandaging group [62]; MLD, IPC, and exercise in two groups, with bandage added to one group, but no intergroup comparisons [58]; and IPC, IPC plus muscle electrostimulation, IPC plus magnetic therapy, or IPC plus both electrostimulation and magnetic therapy, with the largest percent change in limb volume occurring in the last group (p < 0.05) [59].

Two studies examined whether the time of treatment initiation affected outcomes. The first study compared treatment initiated within 1 year of breast cancer surgery to initiation within 1 or 2 years. Treatment in both groups was a combination of MLD, IPC, bandage, and exercise. Faster reduction of arm swelling was observed in the group with earlier treatment initiation [63]. Conversely, the second study found no differences between groups when treatment was initiated 3 months versus 12 months following SE diagnosis. The treatment regimen in this study was physical therapy, electrostimulation, massage, and IPC [64].

The non-English-language studies mirrored the high degree of heterogeneity observed in the English-language studies, e.g., different treatment combinations, varying lengths of follow-up. This heterogeneity prevented us from drawing clear conclusions to answer the key questions. The non-English articles did not contain substantive new information to supplement or alter our English-language findings.

Discussion

Most extracted studies were conducted in persons with a history of breast cancer. One must be prudent before generalizing these studies' results to persons with other conditions.

Many studies showed that most active treatments reduced the size of lymphatic limbs, although extensive study heterogeneity in areas such as length of follow-up, treatment protocols, comparators, and outcome measures prevented us from assessing whether any one treatment was superior. The extracted studies did not contain reports of treatment benefits in any subgroup of patients.

Harms were reported in a small number of studies. These harms were rare and mild, and unlikely to be major clinical issues.

The methodological quality of the extracted studies was generally 'fair'. The authors of some studies omitted the reporting of fundamental elements of their research, such as the blinding of outcome assessors. Quality did not generally affect our interpretation of answers to the key questions.

Research recommendations

Treatment protocols should be clearly described in published RCT reports (describing the comparator as 'usual care' is insufficient). If researchers believe a priori that important subgroup effects are possible, then the study should be powered to detect effects in these subgroups. Since a multiplicity of outcomes exists in SE research, researchers should develop a short list of preferred study outcomes. This will facilitate between-study comparisons and help make meta analyses feasible.

Experimental and comparator treatments must be clearly labeled and the comparator should be a standard treatment regimen for SE. Although sham treatments (e.g., laser) may satisfy minimum regulatory requirements for showing effectiveness, the clinical utility of a novel treatment is best demonstrated against an accepted standard treatment. Maintenance therapies, where used, should be clearly described by study authors. Blinding of study participants, clinicians, and healthcare professionals who administer treatment may not be possible due to the nature of the therapies; however, at a minimum, researchers should blind outcome assessors to treatment.

To avoid the publication of ambiguous trial reports, study authors should use existing quality scales [17–19, 65] and the 2010 CONSORT statement for RCTs [66] as templates for producing RCT manuscripts. One of the extracted studies provides a good example of reporting an RCT's results [41].

Most of the extracted studies involved SE to the upper extremities. Few studies involved lower limb SE, despite its high incidence from cancer treatment [4]. More RCTs should be conducted in persons with SE of the lower limbs.

Another issue concerns whether treatment for the condition preceding SE would affect outcomes of conservative therapy for SE. For example, would patients treated with radiation therapy for breast cancer respond better to MLD than patients treated with lymphadenectomy? Research into this area could provide evidence to guide selection of SE therapy.

Conclusions

Scientists have conducted a great deal of research into the treatment of SE. However, the literature contains no evidence to suggest the most effective treatment. Harms from treatment are minor and likely to have little clinical impact. The field of research into treating SE is open to advancement and we hope this review will guide future research in the area.

References

Warren AG, Brorson H, Borud LJ, Slavin SA: Lymphedema: a comprehensive review. Ann Plast Surg. 2007, 59: 464-472. 10.1097/01.sap.0000257149.42922.7e.

Simonian SJ, Morgan CL, Tretbar LL, Blondeau : Lymphedema: Diagnosis and Treatment. Differential diagnosis of lymphedema. Edited by: Tretbar LL, Morgan CL, Lee BB, Simonian SJ, Blondeau B. 2007, London: Springer, 12-20.

Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G: Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008, 59: 324-331. 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.04.013.

Rockson SG, Rivera KK: Estimating the population burden of lymphedema. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008, 1131: 147-154. 10.1196/annals.1413.014.

Morgan CL: Lymphedema: Diagnosis and Treatment. Medical management of lymphedema. Edited by: Tretbar LL, Morgan CL, Lee BB, Simonian SJ, Blondeau B. 2007, London: Springer, 43-54.

Bernas M, Witte M, Kriederman B, Summers P, Witte C: Massage therapy in the treatment of lymphedema. Rationale, results, and applications. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2005, 24: 58-68.

Zuther J: Traditional massage therapy in the treatment and management of lymphedema. Massage Today. 2002, 2: 1-5. [http://www.massagetoday.com/mpacms/mt/article.php?id=10475]

Cheville AL, McGarvey CL, Petrek JA, Russo SA, Taylor ME, Thiadens SR: Lymphedema management. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003, 13: 290-301. 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00035-3.

International Society of Lymphology: The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema. Consensus document of the international society of lymphology. Lymphology. 2003, 36: 84-91.

Morris RJ: Intermittent pneumatic compression-systems and applications. J Med Eng Technol. 2008, 32: 179-188. 10.1080/03091900601015147.

Carati CJ, Anderson SN, Gannon BJ, Piller NB: Treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema with low-level laser therapy: a double blind, placebo-controlled trial [erratum appears in Cance 2003, 98:2742]. Cancer. 2003, 98: 1114-1122. 10.1002/cncr.11641.

Moseley AL, Carati CJ, Piller NB: A systematic review of common conservative therapies for arm lymphoedema secondary to breast cancer treatment. Ann Oncol. 2007, 18: 639-646.

Oremus M, Walker K, Dayes I, Raina P: Diagnosis and Treatment of Secondary Lymphedema. Contract HHSA 290 2007 10060 I. 2010, Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Florez-Garcia MT, Valverde-Carrillo MD: Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions in the management of lymphedema postmastectomy. Rehabitation. 2007, 41: 126-134.

Kligman L, Wong RK, Johnston M, Laetsch NS: The treatment of lymphedema related to breast cancer: a systematic review and evidence summary. Support Care Cancer. 2004, 12: 421-431. 10.1007/s00520-004-0627-0.

Badger C, Preston N, Seers K, Mortimer P: Physical therapies for reducing and controlling lymphoedema of the limbs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004, 4: CD003141-

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary?. Control Clin Trials. 1996, 17: 1-12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Oremus M, Wolfson C, Perrault A, Demers L, Momoli F, Moride Y: Interrater reliability of the modified Jadad quality scale for systematic reviews of Alzheimer's disease drug trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001, 12: 232-236. 10.1159/000051263.

Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, [http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp]

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Methods Reference Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (Draft). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, [http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/repFiles/2007_10DraftMethodsGuide.pdf]

Andersen L, Hojris I, Erlandsen M, Andersen J: Treatment of breast-cancer-related lymphedema with or without manual lymphatic drainage-a randomized study. Acta Oncol. 2000, 39: 399-405. 10.1080/028418600750013186.

Bertelli G, Venturini M, Forno G, Macchiavello F, Dini D: Conservative treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema: a controlled, randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 1991, 2: 575-578.

Bialoszewski D, Wozniak W, Zarek S: Clinical efficacy of kinesiology taping in reducing edema of the lower limbs in patients treated with the ilizarov method-preliminary report. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2009, 11: 46-54.

Damstra RJ, Partsch H: Compression therapy in breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized, controlled comparative study of relation between volume and interface pressure changes. J Vasc Surg. 2009, 49: 1256-1263. 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.12.018.

Didem K, Ufuk YS, Serdar S, Zumre A: The comparison of two different physiotherapy methods in treatment of lymphedema after breast surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005, 93: 49-54. 10.1007/s10549-005-3781-2.

Dini D, Del Mastro L, Gozza A, Lionetto R, Garrone O, Forno G, Vidili G, Bertelli G, Venturini M: The role of pneumatic compression in the treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema. A randomized phase III study. Ann Oncol. 1998, 9: 187-190. 10.1023/A:1008259505511.

Hayes SC, Reul-Hirche H, Turner J: Exercise and secondary lymphedema: safety, potential benefits, and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009, 41: 483-489.

Hou C, Wu X, Jin X: Autologous bone marrow stromal cells transplantation for the treatment of secondary arm lymphedema: a prospective controlled study in patients with breast cancer related lymphedema. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008, 38: 670-674. 10.1093/jjco/hyn090.

Irdesel J, Kahraman CS: Effectiveness of exercise and compression garments in the treatment of breast cancer related lymphedema. Turkiye Fiziksel Tip ve Rehabilitasyon Dergisi. 2007, 53: 16-21.

Jahr S, Schoppe B, Reisshauer A: Effect of treatment with low-intensity and extremely low-frequency electrostatic fields (deep oscillation) on breast tissue and pain in patients with secondary breast lymphoedema. J Rehabil Med. 2008, 40: 645-650. 10.2340/16501977-0225.

Johansson K, Lie E, Ekdahl C, Lindfeldt J: A randomized study comparing manual lymph drainage with sequential pneumatic compression for treatment of postoperative arm lymphedema. Lymphology. 1998, 31: 56-64.

Kaviani A, Fateh M, Yousefi NR, Alinagi-Zadeh MR, Ataie-Fashtami L: Low-level laser therapy in management of postmastectomy lymphedema. Lasers Med Sci. 2006, 21: 90-94. 10.1007/s10103-006-0380-3.

Kessler T, de Bruin E, Brunner F, Vienne P, Kissling R: Effect of manual lymph drainage after hindfoot operations. Physiother Res Int. 2003, 8: 101-110. 10.1002/pri.277.

Kozanoglu E, Basaran S, Paydas S, Sarpel T: Efficacy of pneumatic compression and low-level laser therapy in the treatment of postmastectomy lymphoedema: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2009, 23: 117-124. 10.1177/0269215508096173.

Lau RW, Cheing GL: Managing postmastectomy lymphedema with low-level laser therapy. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009, 27: 763-769. 10.1089/pho.2008.2330.

Maiya AG, Olivia ED, Dibya A: Effect of low energy laser therapy in the management of post-mastectomy lymphoedema. Physiotherapy Singapore. 2008, 11: 2-5.

McKenzie DC, Kalda AL: Effect of upper extremity exercise on secondary lymphedema in breast cancer patients: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 2003, 21: 463-466. 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.069.

McNeely ML, Magee DJ, Lees AW, Bagnall KM, Haykowsky M, Hanson J: The addition of manual lymph drainage to compression therapy for breast cancer related lymphedema: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004, 86: 95-106. 10.1023/B:BREA.0000032978.67677.9f.

Pilch U, Wozniewski M, Szuba A: Influence of compression cycle time and number of sleeve chambers on upper extremity lymphedema volume reduction during intermittent pneumatic compression. Lymphology. 2009, 42: 26-35.

Radakovk N, Popovic-Petrovic S, Vranjes N, Petrovic T: A comparative pilot study of the treatment of arm lymphedema by manual drainage and sequential external pneumatic compression (SEPC) after mastectomy. Arch Oncol. 1998, 6: 177-178.

Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, Cheville A, Smith R, Lewis-Grant L, Bryan CJ, Williams-Smith CT, Greene QP: Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. New Engl J Med. 2009, 361: 664-673. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810118.

Schmitz KH, Troxel AB, Cheville A, Grant LL, Bryan CJ, Gross CR, Lytle LA, Ahmed RL: Physical activity and lymphedema (the PAL trial): assessing the safety of progressive strength training in breast cancer survivors. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009, 30: 233-245. 10.1016/j.cct.2009.01.001.

Shaw C, Mortimer P, Judd PA: A randomized controlled trial of weight reduction as a treatment for breast cancer-related lymphedema. Cancer. 2007, 110: 1868-1874. 10.1002/cncr.22994.

Shaw C, Mortimer P, Judd PA: Randomized controlled trial comparing a low-fat diet with a weight-reduction diet in breast cancer-related lymphedema. Cancer. 2007, 109: 1949-1956. 10.1002/cncr.22638.

Sitzia J, Sobrido L, Harlow W: Manual lymphatic drainage compared with simple lymphatic drainage in the treatment of post-mastectomy lymphoedema. Physiotherapy. 2002, 88: 99-107. 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)60933-9.

Szuba A, Achalu R, Rockson SG: Decongestive lymphatic therapy for patients with breast carcinoma-associated lymphedema. A randomized, prospective study of a role for adjunctive intermittent pneumatic compression. Study # 1. Cancer. 2002, 95: 2260-2267. 10.1002/cncr.10976.

Szuba A, Achalu R, Rockson SG: Decongestive lymphatic therapy for patients with breast carcinoma-associated lymphedema. A randomized, prospective study of a role for adjunctive intermittent pneumatic compression. Study # 2. Cancer. 2002, 95: 2260-2267. 10.1002/cncr.10976.

Tsai HJ, Hung HC, Yang JL, Huang CS, Tsauo JY: Could Kinesio tape replace the bandage in decongestive lymphatic therapy for breast-cancer-related lymphedema? A pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2009, 17: 1353-1360. 10.1007/s00520-009-0592-8.

Wilburn O, Wilburn P, Rockson SG: A pilot, prospective evaluation of a novel alternative for maintenance therapy of breast cancer-associated lymphedema. BMC Cancer. 2006, doi:10.1186/1471-2407-6-84

Williams AF, Vadgama A, Franks PJ, Mortimer PS: A randomized controlled crossover study of manual lymphatic drainage therapy in women with breast cancer-related lymphoedema. Eur J Cancer Care. 2002, 11: 254-261. 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2002.00312.x.

Balzarini A, Pirovano C, Diazzi G, Olivieri R, Ferla F, Galperti G, Sensi S, Martino G: Ultrasound therapy of chronic arm lymphedema after surgical treatment of breast cancer. Lymphology. 1993, 26: 128-134.

Berlin E, Gjores JE, Ivarsson C, Palmqvist I, Thagg G, Thulesius O: Postmastectomy lymphoedema. Treatment and a five-year follow-up study. Int Angiol. 1999, 18: 294-298.

Brambilla L, Tourlaki A, Ferrucci S, Brambati M, Boneschi V: Treatment of classic Kaposi's sarcoma-associated lymphedema with elastic stockings. J Dermatol. 2006, 33: 451-456. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00108.x.

Frischenschlager O, Fialka V, Schindt L: Comparison of two rehabilitation programmes for lymphedema following ablatio mammae: emotional well-being. Eur J Phys Med Rehabil. 1991, 1: 123-125.

Johansson K, Albertsson M, Ingvar C, Ekdahl C: Effects of compression bandaging with or without manual lymph drainage treatment in patients with postoperative arm lymphedema. Lymphology. 1999, 32: 103-110.

Pinell XA, Kirkpatrick SH, Hawkins K, Mondry TE, Johnstone PA: Manipulative therapy of secondary lymphedema in the presence of locoregional tumors. Cancer. 2008, 112: 950-954. 10.1002/cncr.23242.

Herpertz U: Outcome of various inpatient lymph drainage procedures [German]. Zeitschrift fur Lymphologie-Journal of Lymphology. 1996, 20: 27-30.

Hanasz-Sokolowska D, Kazmierczak U, Hagner W, Kazmierczak M: The effectiveness of conservative methods of rehabilitation (PT) in treatment of lymphoedema after mastectomy operation [Polish]. Fizjoterapia Polska. 2006, 6: 67-71.

Gerasimenko VN, Grushina TI, Lev SG: A complex of conservative rehabilitation measures in postmastectomy edema [Russian]. Vopr Onkol. 1990, 36: 1479-1485.

Lee ES, Kim SH, Kim SM, Sun JJ: Effects of educational program of manual lymph massage on the arm functioning and the quality of life in breast cancer patients [Korean]. Daehan Ganho Haghoeji. 2005, 35: 1390-1400.

Dittmar A, Krause D: A comparison of intermittent compression with single and multi-chamber systems in treatment of secondary arm lymphedema following mastectomy [German]. Zeitschrift fur Lymphologie-Journal of Lymphology. 1990, 14: 27-31.

Ferrandez J: Assessment of two compressive bandages for secondary lymphedema of the upper limb: a prospective multicentric study [French]. Kinesitherapie Revue. 2007, 67: 30-35.

Husarovicova E, Husarovicova V: The rehabilitation influence to reduction of lymphoedema [Slovak]. Rehabilitacia. 2006, 43: 53-57.

Petruseviciene D, Krisciunas A, Sameniene J: Efficiency of rehabilitation methods in the treatment of arm lymphedema after breast cancer surgery [Lithuanian]. Medicina (Kaunas). 2002, 38: 1003-1008.

Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J: The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003, doi:10.1186/1471-2288-3-25

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group: CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010, 8: 18-10.1186/1741-7015-8-18.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/12/6/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (contract no. HHSA 290-2007-10060-I).

The authors of this manuscript are responsible for its content. Statements in the manuscript should not be construed as endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

This article is based on a technology report developed for and presented at a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee meeting held November 18, 2009 http://www.cms.gov/mcd/viewmcac.asp?from2=viewmcac.asp&where=index&mid=51&.

Mark Oremus holds a Career Scientist Award from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care and the McLaughlin Foundation Professorship in Population and Public Health.

Parminder Raina holds the Raymond and Margaret Labarge Chair in Research and Knowledge Application for Optimal Aging and a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Geroscience.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors participated in the conception and design of the study. MO and ID summarized the extracted data. MO wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Oremus, M., Dayes, I., Walker, K. et al. Systematic review: conservative treatments for secondary lymphedema. BMC Cancer 12, 6 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-6