Abstract

Background

Metabolic genes have been associated with the function of metabolizing and detoxifying environmental carcinogens. Polymorphisms present in these genes could lead to changes in their metabolizing and detoxifying ability and thus may contribute to individual susceptibility to different types of cancer. We investigated if the individual and/or combined modifying effects of the CYP1A1 MspI T6235C, GSTM1 present/null, GSTT1 present/null and GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphisms are related to the risk of developing lung cancer in relation to tobacco consumption and occupation in Asturias, Northern Spain.

Methods

A hospital-based case–control study (CAPUA Study) was designed including 789 lung cancer patients and 789 control subjects matched in ethnicity, age, sex, and hospital. Genotypes were determined by PCR or PCR-RFLP. Individual and combination effects were analysed using an unconditional logistic regression adjusting for age, pack-years, family history of any cancer and occupation.

Results

No statistically significant main effects were observed for the carcinogen metabolism genes in relation to lung cancer risk. In addition, the analysis did not reveal any significant gene-gene, gene-tobacco smoking or gene-occupational exposure interactions relative to lung cancer susceptibility. Lastly, no significant gene-gene combination effects were observed.

Conclusions

These results suggest that genetic polymorphisms in the CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 metabolic genes were not significantly associated with lung cancer risk in the current study. The results of the analysis of gene-gene interactions of CYP1A1 MspI T6235C, GSTM1 present/null, GSTT1 present/null and GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphisms in lung cancer risk indicate that these genes do not interact in lung cancer development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Established risk factors for lung cancer include exposure to cigarette- and environmental-derived pro-carcinogens. Cigarette smoking accounts for 80% to 90% of cases among men and 55% to 80% of cases among women [1]. Occupational exposures in industrial facilities account for an additional 9% to 15% of lung cancer cases [2]. However, although cigarette smoking and occupation are the major causes of lung cancer, only a small fraction of smokers and workers in high-risk occupations develop this disease. This suggests other causes, including genetic susceptibility, may contribute to the variation in individual lung cancer risk. This genetic susceptibility may partially result from inherited polymorphisms in the genes involved in carcinogen metabolism [3–5]. Thus, many toxic compounds implicated in carcinogenesis require both activation by metabolic enzymes classified as Phase I and detoxification by enzymes classified as Phase II. Genetic changes in genes that encode metabolic Phase I enzymes and detoxification Phase II enzymes are linked to increases in metabolic activation and decreases in metabolic detoxification of environmentally derived pro-carcinogens and may increase lung cancer susceptibility.

Phase I enzymes (e.g., CYP) oxidize a wide range of substrates, resulting in metabolically active carcinogens. For instance, CYP1A1 is responsible for the metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g., benzo[a]pyrene), a leading pro-carcinogen found in cigarette smoke and environmental pollution [6]. In addition, the CYP1A1 MspI polymorphism in the 3’-flanking region of the CYP1A1 gene [7] is in strong linkage disequilibrium with a non-synonymous SNP of an isoleucine to valine amino acid change at codon 462 [8]. Studies suggest that these 2 CYP1A1 SNPs are implicated in lung cancer risk [9–11].

Phase II enzymes (e.g., the GST supergene family) play a central role in the detoxification of toxic and carcinogenic electrophilic compounds. GSTs are a large family of cytosolic enzymes that catalyze the detoxification of potential carcinogens through a conjugation with reduced glutathione. GSTM1 and GSTP1 metabolize large hydrophobic electrophiles, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-derived epoxides [12]. GSTT1, on the other hand, is involved in the metabolism of smaller compounds, such as monohalomethane and ethylene oxide [13]. GSTs also metabolize compounds formed during oxidative stress, such as hydroperoxides and oxidized lipids, and they are transcriptionally activated during oxidative stress [14].

Certain genetic variants in the glutathione S-transferase genes, such as the GSTM1 and GSTT1 null polymorphisms, are prevalent among 50% and 20% of Caucasians, respectively [15], result in the lack of active enzyme [16]. Meta-analyses have indicated that the carriers of GSTM1 null or GSTT1 null genotypes have a slightly higher risk of developing lung cancer compared to carriers of at least one functional allele [17–19]. GSTP1 is the major isoenzyme expressed in human lung tissue [20]. A A/G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) located within the substrate-binding domain of the GSTP1 results in an isoleucine to valine amino acid change at codon 105 (Ile105Val). Notably, the valine allele is associated with a lower conjugating activity when compared to the isoleucine allele [21–23]. The frequency distribution of the GSTP1 Val allele varies across racial/ethnic groups [20]. However, epidemiological studies of the impact of the GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphism on lung cancer risk, including two meta-analyses, show inconsistent results [19, 24–27].

Many studies investigating the association between the CYP1A1 MspI T6235C, GSTM1 present/null, GSTT1 present/null, and GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphisms and lung cancer risk have been limited by small sample sizes, leading to a lack of statistical power [28–31]. Furthermore, pooled analyses to increase sample size have led to conflicting results between groups, most likely due to population differences (i.e., ethnicity) or failure to control for other potential confounders, including age and sex [32]. Therefore, the four genes analysed in this study encode enzymes involved in the metabolism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and aromatic amines, which are procarcinogens present in both smoking and occupation, and thus, both variables must be controlled for in the analysis. This study will show an analysis of occupation as a method to verify whether individuals who possess at least one variant allele of the polymorphisms studied and belong to list A occupation have a higher risk of lung cancer than those individuals with the wild-type genotype.

To examine whether genetic polymorphisms in Phase I and Phase II metabolic genes are associated with lung cancer risk, we studied 4 polymorphisms in the CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 metabolic genes, individually and combined, in a large hospital-based case–control study of lung cancer including 789 lung cancer cases and 789 controls from a Caucasian population in Asturias, Northern Spain. Moreover, we analyzed the possible interactions gene-tobacco and gene-occupational exposure.

Methods

Study population

The CAPUA (Lung Cancer in Asturias [Cáncer de Pulmón en Asturias], Spain) study is a hospital-based, case–control study conducted by the Molecular Epidemiology Cancer Unit at the University Institute of Oncology (University of Oviedo). Details of the study design and methods have been described elsewhere [33–37]. Briefly, from October 2000 to December 2010, a standard protocol was used to recruit incident cases of histologically confirmed lung cancer at Asturias’ four main hospitals (the Cabueñes Hospital in Gijón, San Agustin Hospital in Avilés, General Hospital in Oviedo and Álvarez-Buylla Hospital in Mieres). In addition, controls were selected from patients admitted to those hospitals with diagnoses unrelated to the exposures of interest and individually matched by ethnicity, gender, age (± 5 years) and hospital. The main specific pathologies of the final controls selected were as follows: 36.6% inguinal and abdominal hernias (ICD-9: 550–553), 29.3% injuries (ICD-9: 800–848, 860–869, 880–897), and 12.5% intestinal obstructions (ICD-9: 560, 569, 574). The CAPUA study was approved by the respective ethics committees of the hospitals involved, and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

During the first hospital admission, information on known or potential risk factors for lung cancer was collected personally by trained interviewers using computer-assisted questionnaires. These structured questionnaires collected data from each participant on age, gender, socio-demographic characteristics, recent and past tobacco use, personal and family history of lung cancer, and occupational history.

Participants were categorized by smoking status into three groups: non-smokers, defined as subjects who had not smoked at least one cigarette per day regularly for six months or longer in their lifetimes; former smokers that included regular smokers who had stopped smoking at least five years before the interview; and current smokers who met none of the previous criteria. Smoking intensity (pack-years (PY)) was defined as the number of packs of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years of smoking. Subjects were also categorized as light (<37 PY) or heavy (≥37 PY) smokers, based on the mean cumulative tobacco consumption in the control group.

For each job held for a minimum of 6 months or longer, we obtained information on the industry name, production type, job title, and the year in which the job began and ended. Occupations and industries were coded using the 1977 Standard Occupational Classification [38] and 1972 Standard Industrial Classification schemes [39]. Lastly, each coded occupation was categorized according to the list of occupations known to be associated with lung cancer (List A) based on evaluations of carcinogenic risks by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [40, 41]. This list is periodically updated and has been extensively used worldwide as a standardized tool to quantify the burden of occupational lung cancer [42–47]. Some examples of List A occupations among our individuals are the following: Arsenic, uranium, iron-ore, asbestos and talc miners; Ceramic and pottery workers; Iron and steel founding (casters, moulders and core makers); Copper, zinc, cadmium, aluminum, nickel chromates, beryllium blue collar workers; Platters; Shipyard/dockyard, railroad manufacture workers; Coke plant and gas production workers; Insulators, roofers and asphalt workers; and painters.

Genotype analysis

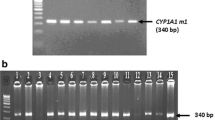

Laboratory personnel were blinded to case and control status. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples (97.6% of total) or exfoliated buccal cells (2.4% of total) as previously described [48]. As quality control steps, genotyping was repeated randomly in at least 5% of the samples, and two of the authors independently reviewed all results. In this quality control there was 100% concordance between the replicate samples and genotype calls between the independent evaluator. The null genotype of GSTM1 and GSTT1 was determined by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using β-globin as an internal positive control and previously described primers and conditions [49]. The polymorphisms in CYP1A1 and GSTP1 (rs1695) were analysed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) combined with restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) using previously described primers and conditions [50, 51]. PCR was performed in a 10 μl mixture containing 20 ng of genomic DNA, 0.25 mM of each dNTP, 0.5 units of Taq polymerase (Biotools), and 10 pmol of each primer in a 1x PCR buffer. PCR products were digested overnight with the indicated restriction enzyme at 37°C. DNA fragments were resolved on agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. To verify that the data obtained by RFLP coincided with the allele sequence, representative fragments were further purified for PCR-directed sequencing to confirm the different polymorphisms (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant departures from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium were evaluated by comparing observed and expected genotype frequencies among controls using a chi-square test with 2 degrees of freedom. Differences in the distribution of categorical data (gender, smoking status, family history of lung cancer, and occupational status) were tested using a chi-square test. Continuous variables that were not normally distributed among controls (age, PY) were assessed using a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. Crude odd ratios (ORs) were calculated using Wolf's method [52]. Multivariate unconditional logistic regression analysis with adjustment for age, family history of any cancer, tobacco consumption and worker in list A occupation (no, yes) was performed to calculate adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions were estimated using a logistic regression model, which included an interaction term as well as variables for exposure (tobacco consumption, family history of any cancer, and worker in list A occupation), genotypes (CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTT1 or GSTP1) and potential confounders (age).

To analyze the gene-gene interactions, the genotypes of two genes were combined and sorted into four categories consisting of no risk alleles (the reference group), no risk allele for the first gene and any risk allele for the second, any risk allele for the first gene and no risk allele for the second, and two risk alleles. For CYP1A1 the C-allele was classified as the putative high risk allele. In the case of GSTs genes, the putative high-risk alleles were the ≥1 null allele for GSTM1, the ≥1 null allele for GSTT1 and, finally, the Val allele for GSTP1.

The sample size of our study for an allele frequency between 11–35% is sufficient to detect ORs greater than 1.34 or lower than 0.69 with more than 80% power assuming a dominant genetic model.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 8.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

Subject characteristics

The analysis included 789 lung cancer cases and 789 controls from a Caucasian population of Asturias, Northern Spain (CAPUA Study, acronym for CÁncer de PUlmón en Asturias [Lung Cancer in Asturias]). There were no statistically significant differences among the cases and controls regarding gender. There were statistically significant differences comparing the cases to controls regarding median age (67 vs. 66), tobacco smoking pack-years (PY) (54 vs. 30.1), family history of lung cancer (11.4% vs. 6.5%) and list A occupation status (List A include occupations known to be associated with lung cancer) (8.8% vs. 13.2%). There were more current smokers (63.7% vs. 34.3%) and more heavy smokers (62.29 vs. 36.89 PY) among the cases than among the controls. Histologically, squamous cell carcinoma (39.8%) and adenocarcinoma (31.3%) were the main types of lung cancer (summarized in Table 1).

We evaluated the impact of polymorphisms detected in 4 in Phase I and Phase II metabolism genes (CYP1A1 MspI T6235C, GSTM1 present/null, GSTT1 present/null and GSTP1 Ile105Val) on the risk of developing lung cancer. Within our study set, in heritance of at least one GST (M1, T1) deletion or GSTP1 105Val alleles were fairly common among controls with frequencies ranging from 21.3-58.1%, as detailed in Table 2. The genotype frequencies were comparable to other many European populations. The genotype frequencies did not substantially deviate from expected distribution under the Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (p ≥ 0.05).

We evaluated the main effects of phase I/phase II xenobiotic metabolism genes (CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTP1 and GSTT1) in relation to lung cancer susceptibility using univariate as well as multivariate statistics. No significant individual gene effects were observed among carriers of one or more CYP1A1 MspI 6235C (OR = 1.13; 95% CI = 0.86-1.49); GSTM1 null (OR = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.76-1.19); GSTT1 null (OR = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.64-1.12); GSTP1 Val (OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.66-1.05), as summarized in Table 2.

Individual effects of CYP1A1 and GST SNPs on lung cancer and histological subtypes

No association was found between CYP1A1 MspI T6235C polymorphism and lung cancer risk (adjusted OR = 1.16; 95% CI = 0.87-1.53; adjusted OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.31-2.20; adjusted OR = 1.13; 95% CI = 0.86-1.49 for T/C genotype, C/C genotype and T/C + C/C genotypes, respectively).

For the GSTM1 present/null polymorphism, the frequency of the GSTM1 null genotype was lower in the cases (51.7%) than in the controls (53.9%), although not statistically significant. When we analyzed the association between the GSTM1 genotypes and lung cancer risk, we found that the ≥1 null allele was no associated with the risk of developing lung cancer (adjusted OR = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.76-1.19).

In the case of the GSTT1 present/null polymorphism the frequency of the GSTT1 null genotype was lower in the cases (20.4%) than in the controls (21.3%), although not statistically significant. We did not find any evidence of an association between the GSTM1 genotypes and lung cancer risk.

Finally, the frequency of the GSTP1 Val allele was 0.338 in the cases and 0.349 in the controls. The frequency of the Val/Val genotype was slightly higher in the cases (12.3%) than in the controls (11.7%). When we analysed the association between the GSTP1 genotypes and lung cancer risk, we found no association between individuals with the variant genotype Val/Val or the carriers of variant allele Val (Ile/Val + Val/Val) and the risk of developing lung cancer (adjusted OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.57-1.19 and adjusted OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.66-1.05, respectively) (Table 2).

Individual effects of carcinogen metabolism genes on histological lung cancer subtype

The stratified analysis by histological type of the CYP1A1 MspI T6235C, GSTM1 present/null, GSTT1 present/null, GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphisms did not reveal any statistically significant association (Table 3).

Gene-environment and gene-gene interactions

An analysis of the interaction of each variant carcinogen metabolism gene alone and tobacco consumption in lung cancer risk showed that there is no gene-environment interaction (Table 4). In addition, no association was found in the analysis of the interaction between GSTM1 present/null, GSTT1 present/null and GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphisms and occupation in lung cancer risk (each gene analysed separately with occupation). However, the case of the C-allele variant in the CYP1A1 gene could represent a possible interaction with occupation (adjusted OR [95%CI]: 2.20 [1.11-4.35] for workers in occupations included in list A), as shown in Table 5.

None of the 6 possible paired combinations for the CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 polymorphisms showed a gene-gene interaction (Table 6).

Discussion

In this study, we have examined whether individual or joint modifying effects among four polymorphic metabolic genes were implicated in the development of lung cancer in a Caucasian population from Asturias, Northern Spain. Our results suggest that the polymorphisms CYP1A1 MspI T6235C, GSTM1 present/null, GSTT1 present/null and GSTP1 Ile105Val are not associated with lung cancer risk or cancer subtype.

The analysis performed in the present study between the polymorphisms studied and tobacco consumption did not reveal any gene-environmental interaction. The results showed higher lung cancer risk with higher tobacco consumption. Finally, no association was observed in the analysis of interaction between the polymorphisms studied and occupation.

Our study has several strengths, including high participation levels of eligible cases from a homogeneous population of similar ancestry and all of our control subjects being under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. In addition, all of our cases were pathologically confirmed. We also applied a strong quality control from genotyping (explained in detail in Methods section). Inevitably, the use of hospital-based controls is a potential limitation. The hospitals from which the cases were recruited were reference centers for all patients requiring hospitalization. Our controls were referred to these hospitals due to the presence of acute health conditions that were unrelated to lung cancer risk factors. There is always a chance of recall bias consisting of a systematic error due to differences in memories of cigarette smoking habits or occupational exposures between cases and controls. Structured interviews, like those used in this study, help to minimize this type of risk. Moreover, the prevalence of tobacco smoking and occupational exposure was in agreement with the literature. Our sample size is not large enough to find conclusive results in interaction analysis. Other genes that could participate in xenobiotic metabolism were not considered on the current study, which is another possible limitation. Therefore, our future objective is to validate these results with more individuals and powerful genotyping techniques.

Several studies have shown that the CYP1A1 MspI T6235C polymorphism is associated with an increased lung cancer risk in Asian populations, especially in relation to tobacco smoking [11, 32]. However, previous research, including a review of 20 studies [9] and two pooled analyses [32, 53], in addition to our results suggest that there is not an established association between this polymorphism and increased lung cancer risk in Caucasian populations.

Although biological studies have shown evidence of variant genotypes in the GST genes, including GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1, resulting in reduced enzymatic activity in the cell, epidemiological studies do not support these findings. Many studies, including several meta-analyses and pooled analyses, support our finding that these three polymorphisms are not associated with lung cancer risk [17–19, 24–27].

A large meta-analysis conducted in 2006, including 19,729 cases and 25,931 controls from 117 studies [19], found an increased lung cancer risk associated with the GSTM1 present/null polymorphism. However, when only studies with more than 500 case/control pairs were considered, no association was observed. Similarly, pooled analyses with either non-smokers from 23 studies [53] on cases from a Caucasian population younger than 60 years old with non-small cell lung cancer [4] were not significantly related to lung cancer or disease progression.

In relation to the GSTT1 present/null polymorphism, two meta-analyses and three pooled analyses have been performed to date. Similarly to the GSTM1 present/null polymorphism, the meta-analysis carried out by Ye et al. [19], including 9,636 cases and 12,322 controls from 44 studies, revealed an increased lung cancer risk associated with the variant genotype of GSTT1. However, when only studies with more than 500 case/control pairs were considered, no association was observed. In addition, a meta-analysis of 34 studies found no association between this polymorphism and lung cancer risk in a Caucasian population [18]. The three pooled analyses, one including 34 studies [18], the second with non-smokers from 8 studies [53], and the last including cases of a Caucasian population younger than 60 years old with non-small cell lung cancer [4], showed no statistically significant associations.

Finally, a recent meta-analysis including 8,322 cases and 8,844 controls from 27 studies found no association between the GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphism and lung cancer risk [25] among all study participants or stratified by race/ethnicity. These findings corroborate findings from another meta-analysis of 25 studies with 6,221 cases and 7,602 controls [19] and with a pooled analysis including cases of a Caucasian population younger than 60 years old with non-small cell lung cancer [4].

Analyses of gene-gene interactions are especially important in the glutathione metabolic pathway where multiple enzymes with overlapping functions and shared substrates have been associated with susceptibility to carcinogens and toxic agents. In this study, no association was found probably due to the failure to consider an exhaustive chart of carcinogen metabolism related genes. However, other studies have found positive results in the gene-gene interaction analysis [24, 27, 54], which could support the notion that genome-based lung cancer risk is likely to be influenced by combinations of single risk genes of modest effect as well as synergistic gene-gene interactions.

Although it is well established that occupational exposure is an important risk factor for lung cancer [2] and the metabolic genes studied here are implicated in the metabolism of important occupational carcinogens [6, 12, 13], very few studies on genetic variants in these metabolic genes have been able to take occupation into account because of the difficulty to compile that information. Thus, while several studies have analysed the effect of these polymorphisms on the individual susceptibility to different cancers, particularly bladder cancer, while controlling for occupation [55–58], only five studies to date have controlled by occupational exposure in lung cancer [5, 29, 59–61]. Nazar-Stewart et al. [59] evaluated the occupational exposure to arsenic, asbestos, and welding or diesel products as potential effect modifiers for the GSTM1 present/null, GSTT1 present/null, and GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphisms but found no association. Jourenkova-Mironova et al. [29], Reszka et al. [5], and Risch et al. [60] used occupational exposure as a confounding variable and Yin et al. [61] used occupation as matching variable. No study has used occupational exposure; therefore, we have added to this discussion by evaluating the possible modification of the relationship between workers in high occupational risk and lung cancer development.

Conclusions

In summary, our results suggest that the four genetic polymorphisms studied in the CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 metabolic genes are not associated with lung cancer risk in our total population of Caucasians from Northern Spain. Furthermore, the negative results in the gene-gene interactions analysis seem to indicate that these interactions do not have an association with lung cancer development. Well-designed and powerful epidemiological studies are necessary to determinate the true role of genetic susceptibility in lung cancer.

References

Levi F: Cancer prevention: epidemiology and perspectives. Eur J Cancer. 1999, 35: 1046-1058. 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00094-5.

Spitz MR, Wu X, Wilkinson A, Wei Q: Cancer of the lung. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Third Edition. Edited by: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr. 2006, Oxford University Press, New York, 638-658.

Zienolddiny S, Campa D, Lind H, Ryberg D, Skaug V, Stangeland LB, Canzian F, Haugen A: A comprehensive analysis of phase I and phase II metabolism gene polymorphisms and risk of non-small cell lung cancer in smokers. Carcinogenesis. 2008, 29 (6): 1164-1169. 10.1093/carcin/bgn020.

Skuladottir H, Autrup H, Autrup J, Tjoenneland A, Overvad K, Ryberg D, Haugen A, Olsen JH: Polymorphisms in genes involved in xenobiotic metabolism and lung cancer risk under the age of 60 years. A pooled study of lung cancer patients in Denmark and Norway. Lung Cancer. 2005, 48: 187-199. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.10.013.

Reszka E, Wasowicz W: Significance of genetic polymorphisms in glutathione S-transferase multigene family and lung cancer risk. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2001, 14: 99-113.

Hong JY, Yang CS: Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 as a biomarker of susceptibility to environmental toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 1997, 105 (Suppl 4): 759-762. 10.1289/ehp.97105s4759.

Hayashi S, Watanabe J, Nakachi K, Kawajiri K: Genetic linkage of lung cancer-associated MspI polymorphisms with amino acid replacement in the heme binding region of the human cytochrome P450IA1 gene. J Biochem (Tokyo). 1991, 110: 407-411.

Hayashi SI, Watanabe J, Nakachi K, Kawajiri K: PCR detection of an A/G polymorphism within exon 7 of the CYP1A1 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19: 4797-

Bartsch H, Nair U, Risch A, Rojas M, Wikman H, Alexandrov K: Genetic polymorphism of CYP genes, alone or in combination, as a risk modifier of tobacco-related cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000, 9: 3-28.

Lee KM, Kang D, Clapper ML, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Ono-Kihara M, Kiyohara C, Min S, Lan Q, Marchand Le L, Lin P, Lung ML, Pinarbasi H, Pisani P, Srivatanakul P, Seow A, Sugimura H, Tokudome S, Yokota J, Taioli E: CYP1A1, GSTM1, and GSTT1 polymorphisms, smoking, and lung cancer risk in a pooled analysis among Asian populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008, 17: 1120-1126. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2786.

Vineis P, Veglia F, Benhamou S, Butkiewicz D, Cascorbi I, Clapper ML, Dolzan V, Haugen A, Hirvonen A, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Kihara M, Kiyohara C, Kremers P, Marchand Le L, Ohshima S, Pastorelli R, Rannug A, Romkes M, Schoket B, Shields P, Strange RC, Stucker I, Sugimura H, Garte S, Gaspari L, Taioli E: CYP1A1 T3801 C polymorphism and lung cancer: a pooled analysis of 2451 cases and 3358 controls. Int J Cancer. 2003, 104: 650-657. 10.1002/ijc.10995.

Hayes JD, Pulford DJ: The glutathione S-transferase supergene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of the isoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995, 30: 445-600. 10.3109/10409239509083491.

Landi S: Mammalian class theta GST and differential susceptibility to carcinogens: a review. Mutat Res. 2000, 463: 247-283. 10.1016/S1383-5742(00)00050-8.

Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR: Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005, 45: 51-88. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857.

Garte S, Gaspari L, Alexandrie AK, Ambrosone C, Autrup H, Autrup JL, Baranova H, Bathum L, Benhamou S, Boffetta P, Bouchardy C, Breskvar K, Brockmoller J, Cascorbi I, Clapper ML, Coutelle C, Daly A, Dell'Omo M, Dolzan V, Dresler CM, Fryer A, Haugen A, Hein DW, Hildesheim A, Hirvonen A, Hsieh LL, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Kalina I, Kang D, Kihara M, et al: Metabolic gene polymorphism frequencies in control populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001, 10: 1239-1248.

Rebbeck TR: Molecular epidemiology of the human glutathione S-transferase genotypes GSTM1 and GSTT1 in cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997, 6: 733-743.

Benhamou S, Lee WJ, Alexandrie AK, Boffetta P, Bouchardy C, Butkiewicz D, Brockmoller J, Clapper ML, Daly A, Dolzan V, Ford J, Gaspari L, Haugen A, Hirvonen A, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Kalina I, Kihara M, Kremers P, Marchand Le L, London SJ, Nazar-Stewart V, Onon-Kihara M, Rannug A, Romkes M, Ryberg D, Seidegard J, Shields P, Strange RC, Stucker I, et al: Meta- and pooled analyses of the effects of glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphisms and smoking on lung cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2002, 23: 1343-1350. 10.1093/carcin/23.8.1343.

Raimondi S, Paracchini V, Autrup H, Barros-Dios JM, Benhamou S, Boffetta P, Cote ML, Dialyna IA, Dolzan V, Filiberti R, Garte S, Hirvonen A, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Imyanitov EN, Kalina I, Kang D, Kiyohara C, Kohno T, Kremers P, Lan Q, London S, Povey AC, Rannug A, Reszka E, Risch A, Romkes M, Schneider J, Seow A, Shields PG, Sobti RC, et al: Meta- and pooled analysis of GSTT1 and lung cancer: a HuGE-GSEC review. Am J Epidemiol. 2006, 164: 1027-1042. 10.1093/aje/kwj321.

Ye Z, Song H, Higgins JP, Pharoah P, Danesh J: Five glutathione s-transferase gene variants in 23,452 cases of lung cancer and 30,397 controls: meta-analysis of 130 studies. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e91-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030091.

Watson MA, Stewart RK, Smith GB, Massey TE, Bell DA: Human glutathione S-transferase P1 polymorphisms: relationship to lung tissue enzyme activity and population frequency distribution. Carcinogenesis. 1998, 19: 275-280. 10.1093/carcin/19.2.275.

Ali-Osman F, Akande O, Antoun G, Mao JX, Buolamwini J: Molecular cloning, characterization, and expression in Escherichia coli of full-length cDNAs of three human glutathione S-transferase Pi gene variants. Evidence for differential catalytic activity of the encoded proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 10004-10012. 10.1074/jbc.272.15.10004.

Hu X, Ji X, Srivastava SK, Xia H, Awasthi S, Nanduri B, Awasthi YC, Zimniak P, Singh SV: Mechanism of differential catalytic efficiency of two polymorphic forms of human glutathione S-transferase P1-1 in the glutathione conjugation of carcinogenic diol epoxide of chrysene. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997, 345: 32-38. 10.1006/abbi.1997.0269.

Sundberg K, Johansson AS, Stenberg G, Widersten M, Seidel A, Mannervik B, Jernström B: Differences in the catalytic efficiencies of allelic variants of glutathione transferase P1-1 towards carcinogenic diol epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Carcinogenesis. 1998, 19: 433-436. 10.1093/carcin/19.3.433.

Cote ML, Kardia SL, Wenzlaff AS, Land SJ, Schwartz AG: Combinations of glutathione S-transferase genotypes and risk of early-onset lung cancer in Caucasians and African Americans: a population-based study. Carcinogenesis. 2005, 26: 811-819. 10.1093/carcin/bgi023.

Cote ML, Chen W, Smith DW, Benhamou S, Bouchardy C, Butkiewicz D, Fong KM, Gené M, Hirvonen A, Kiyohara C, Larsen JE, Lin P, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Povey AC, Reszka E, Risch A, Schneider J, Schwartz AG, Sorensen M, To-Figueras J, Tokudome S, Pu Y, Yang P, Wenzlaff AS, Wikman H, Taioli E: Meta- and pooled analysis of GSTP1 polymorphism and lung cancer: a HuGE-GSEC review. Am J Epidemiol. 2009, 169: 802-814. 10.1093/aje/kwn417.

Schneider J, Bernges U, Philipp M, Woitowitz HJ: GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 polymorphism and lung cancer risk in relation to tobacco smoking. Cancer Lett. 2004, 208: 65-74. 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.01.002.

Sorensen M, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Brasch-Andersen C, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Autrup H: Interactions between GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 polymorphisms and smoking and intake of fruit and vegetables in relation to lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007, 55: 137-144. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.010.

Wenzlaff AS, Cote ML, Bock CH, Land SJ, Santer SK, Schwartz DR, Schwartz AG: CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 polymorphisms and risk of lung cancer among never smokers: a population-based study. Carcinogenesis. 2005, 26 (12): 2207-2212. 10.1093/carcin/bgi191.

Jourenkova-Mironova N, Wikman H, Bouchardy C, Voho A, Dayer P, Benhamou S, Hirvonen A: Role of glutathione S-transferase GSTM1, GSTM3, GSTP1 and GSTT1 genotypes in modulating susceptibility to smoking-related lung cancer. Pharmacogenetics. 1998, 8: 495-502. 10.1097/00008571-199812000-00006.

Honma HN, De Capitani EM, Perroud MW, Barbeiro AS, Toro IF, Costa DB, Lima CS, Zambon L: Influence of p53 codon 72 exon4, GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1*B polymorphisms in lung cancer risk in a Brazilian population. Lung Cancer. 2008, 61 (2): 152-162. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.12.014.

Saarikoski ST, Voho A, Reinikainen M, Anttila S, Karjalainen A, Malaveille C, Vainio H, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Hirvonen A: Combined effect of polymorphic GST genes on individual susceptibility to lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998, 77 (4): 516-521. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980812)77:4<516::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-X.

Vineis P, Veglia F, Anttila S, Benhamou S, Clapper ML, Dolzan V, Ryberg D, Hirvonen A, Kremers P, Le Marchand L, Pastorelli R, Rannug A, Romkes M, Schoket B, Strange RC, Garte S, Taioli E: CYP1A1, GSTM1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms and lung cancer: a pooled analysis of gene-gene interactions. Biomarkers. 2004, 9: 298-305. 10.1080/13547500400011070.

Fernandez-Rubio A, Lopez-Cima MF, Gonzalez-Arriaga P, Garcia-Castro L, Pascual T, Marron MG, Tardon A: The TP53 Arg72Pro polymorphism and lung cancer risk in a population of Northern Spain. Lung Cancer. 2008, 61: 309-316. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.01.017.

Gonzalez-Arriaga P, Lopez-Cima MF, Fernandez-Somoano A, Pascual T, Marron MG, Puente XS, Tardon A: Polymorphism +17 C/G in Matrix Metalloprotease MMP8 decreases lung cancer risk. BMC Cancer. 2008, 8: 378-10.1186/1471-2407-8-378.

Leader A, Fernandez-Somoano A, Lopez-Cima MF, Gonzalez-Arriaga P, Pascual T, Marron MG, Tardon A: Educational inequalities in quantity, duration and type of tobacco consumption among lung cancer patients in Asturias: epidemiological analyses. Psicothema. 2010, 22: 634-640.

Lopez-Cima MF, Gonzalez-Arriaga P, Garcia-Castro L, Pascual T, Marron MG, Puente XS, Tardon A: Polymorphisms in XPC, XPD, XRCC1, and XRCC3 DNA repair genes and lung cancer risk in a population of Northern Spain. BMC Cancer. 2007, 7: 162-10.1186/1471-2407-7-162.

Marin MS, Lopez-Cima MF, Garcia-Castro L, Pascual T, Marron MG, Tardon A: Poly (AT) polymorphism in intron 11 of the XPC DNA repair gene enhances the risk of lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004, 13: 1788-1793.

Office of Federal Statistical Policy and Standards: Standard occupational classification manual. 1977, US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Office of Federal Statistical Policy and Standards: Standard industrial classification manual. 1972, US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

International Agency for Research on Cancer: IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 2012, Lyon, http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Classification/index.php. Accessed May 3, 2012

Simonato L, Saracci R: Cancer, occupational. International Labor Organization (ILO). Encyclopedia of Occupational Safety and Health. 1983, ILO, Geneva, 369-375.

Siemiatycki J, Richardson L, Boffetta P: Occupation. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Edited by: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF. 2006, Oxford University Press, New York, 322-354. Third

De Matteis S, Consonni D, Bertazzi PA: Exposure to occupational carcinogensand lung cancer risk. Evolution of epidemiological estimates of attributable fraction. Acta Biomed. 2008, 79 (suppl 1): 34-42.

Siemiatycki J, Richardson L, Straif K, Latreille B, Lakhani R, Campbell S, Rousseau MC, Boffetta P: Listing occupational carcinogens. Environ Health Perspect. 2004, 112 (15): 1447-1459. 10.1289/ehp.7047.

Ahrens W, Merletti F: A standard tool for the analysis of occupational lung cancer in epidemiologic studies. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1998, 4 (4): 236-240.

Mirabelli D, Chiusolo M, Calisti R, Massacesi S, Richiardi L, Nesti M, Merletti F: Database of occupations and industrial activities that involve the risk of pulmonary tumors (in Italian). Epidemiol Prev. 2001, 25 (4–5): 215-221.

Consonni D, De Matteis S, Lubin JH, Wacholder S, Tucker M, Pesatori AC, Caporaso NE, Bertazzi PA, Landi MT: Lung cancer and occupation in a population-based case–control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010, 171: 323-333. 10.1093/aje/kwp391.

Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF: A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16: 1215-10.1093/nar/16.3.1215.

Morari EC, Leite JL, Granja F, da Assumpcao LV, Ward LS: The null genotype of glutathione s-transferase M1 and T1 locus increases the risk for thyroid cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002, 11: 1485-1488.

Ng DP, Tan KW, Zhao B, Seow A: CYP1A1 polymorphisms and risk of lung cancer in non-smoking Chinese women: influence of environmental tobacco smoke exposure and GSTM1/T1 genetic variation. Cancer Causes Control. 2005, 16: 399-405. 10.1007/s10552-004-5476-0.

Wang Y, Spitz MR, Schabath MB, Ali-Osman F, Mata H, Wu X: Association between glutathione S-transferase p1 polymorphisms and lung cancer risk in Caucasians: a case–control study. Lung Cancer. 2003, 40: 25-32. 10.1016/S0169-5002(02)00537-8.

Wolf FM: Meta-analysis: quantitative methods for research synthesis. 1986, Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Raimondi S, Boffetta P, Anttila S, Bröckmoller J, Butkiewicz D, Cascorbi I, Clapper ML, Dragani TA, Garte S, Gsur A, Haidinger G, Hirvonen A, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Kalina I, Lan Q, Leoni VP, Le Marchand L, London SJ, Neri M, Povey AC, Rannug A, Reszka E, Ryberg D, Risch A, Romkes M, Ruano-Ravina A, Schoket B, Spinola M, Sugimura H, Wu X, et al: Metabolic gene polymorphisms and lung cancer risk in non-smokers. An update of the GSEC study. Mutat Res. 2005, 592: 45-57. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.06.002.

Larsen JE, Colosimo ML, Yang IA, Bowman R, Zimmerman PV, Fong KM: CYP1A1 Ile462Val and MPO G-463A interact to increase risk of adenocarcinoma but not squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Carcinogenesis. 2006, 27: 525-532.

Brockmöller J, Kaiser R, Kerb R, Cascorbi I, Jaeger V, Roots I: Polymorphic enzymes of xenobiotic metabolism as modulators of acquired P53 mutations in bladder cancer. Pharmacogenetics. 1996, 6: 535-545. 10.1097/00008571-199612000-00007.

Golka K, Hermes M, Selinski S, Blaszkewicz M, Bolt HM, Roth G, Dietrich H, Prager HM, Ickstadt K, Hengstler JG: Susceptibility to urinary bladder cancer: relevance of rs9642880[T], GSTM1 0/0 and occupational exposure. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2009, 19: 903-906. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328331b554.

Hung RJ, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Malaveille C, Hautefeuille A, Donato F, Gelatti U, Spaliviero M, Placidi D, Carta A, di CA S, Porru S: GST, NAT, SULT1A1, CYP1B1 genetic polymorphisms, interactions with environmental exposures and bladder cancer risk in a high-risk population. Int J Cancer. 2004, 110: 598-604. 10.1002/ijc.20157.

Ma QW, Lin GF, Chen JG, Shen JH: Polymorphism of glutathione S-transferase T1, M1 and P1 genes in a Shanghai population: patients with occupational or non-occupational bladder cancer. Biomed Environ Sci. 2002, 15: 253-260.

Nazar-Stewart V, Vaughan TL, Stapleton P, Van Loo J, Nicol-Blades B, Eaton DL: A population-based study of glutathione S-transferase M1, T1 and P1 genotypes and risk for lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003, 40: 247-258. 10.1016/S0169-5002(03)00076-X.

Risch A, Wikman H, Thiel S, Schmezer P, Edler L, Drings P, Dienemann H, Kayser K, Schulz V, Spiegelhalder B, Bartsch H: Glutathione-S-transferase M1, M3, T1 and P1 polymorphisms and susceptibility to non-small-cell lung cancer subtypes and hamartomas. Pharmacogenetics. 2001, 11: 757-764. 10.1097/00008571-200112000-00003.

Yin L, Pu Y, Liu TY, Tung YH, Chen KW, Lin P: Genetic polymorphisms of NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase, CYP1A1 and microsomal epoxide hydrolase and lung cancer risk in Nanjing, China. Lung Cancer. 2001, 33: 133-141. 10.1016/S0169-5002(01)00182-9.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/12/433/prepub

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all the patients who participated in the study. We would also like to thank our technical colleagues (Molecular Epidemiology of Cancer Unit, University Institute of Oncology of the Principality of Asturias) for collecting the data. This work was partially financed by FIS/Spain grant numbers FIS-01/310, FIS-PI03-0365, and FIS-07-BI060604, FICYT/Asturias grant numbers FICYT PB02-67 and FICYT IB09-133, and the University Institute of Oncology, supported by Obra Social Cajastur-Asturias, Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MFLC carried out the molecular genetic studies and drafted the manuscript. SMAA revised the manuscript. TP participated in the patient enrolment. AFS performed the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. AT conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

López-Cima, M.F., Álvarez-Avellón, S.M., Pascual, T. et al. Genetic polymorphisms in CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTP1 and GSTT1metabolic genes and risk of lung cancer in Asturias. BMC Cancer 12, 433 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-433

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-433