Abstract

Background

Cerebral ischaemia initiates an inflammatory response in the brain and periphery. We assessed the relationship between peak values of plasma interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the first week after ischaemic stroke, with measures of stroke severity and outcome.

Methods

Thirty-seven patients with ischaemic stroke were prospectively recruited. Plasma IL-6, and other markers of peripheral inflammation, were measured at pre-determined timepoints in the first week after stroke onset. Primary analyses were the association between peak plasma IL-6 concentration with both modified Rankin score (mRS) at 3 months and computed tomography (CT) brain infarct volume.

Results

Peak plasma IL-6 concentration correlated significantly (p < 0.001) with CT brain infarct volume (r = 0.75) and mRS at 3 months (r = 0.72). It correlated similarly with clinical outcome at 12 months or stroke severity. Strong associations were also noted between either peak plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration or white blood cell (WBC) count, and all outcome measures.

Conclusions

These data provide evidence that the magnitude of the peripheral inflammatory response is related to the severity of acute ischaemic stroke, and clinical outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cerebral ischaemia initiates an inflammatory response in the brain [1] that is associated with induction of a variety of cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), a pleiotropic cytokine involved in diverse inflammatory functions. IL-6 mRNA and bioactivity are induced rapidly in experimental focal cerebral ischaemia [2, 3], and elevated IL-6 concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of acute stroke patients correlate with infarct volume [4]. However, the role of IL-6 in the central nervous system (CNS) following experimental cerebral ischaemia is not resolved [2, 3, 5, 6].

Systemic inflammatory responses are also evident following inflammation in the CNS, but the relationship between peripheral mediators and CNS events is uncertain [7]. Peripheral infection, which commonly precedes or complicates stroke [8, 9], is also a major stimulus for production of cytokines and an acute phase response. Although most cytokines are only present at biologically effective concentrations at the site of inflammation, IL-6 is a major circulating cytokine produced in response to inflammatory insult and infection, and is a potent stimulus for production of hepatic acute phase proteins [10], induction of fever [11], and activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [12].

The relationship between peripheral inflammatory markers and outcome in stroke patients remains poorly understood. In patients with acute ischaemic stroke, some studies have reported an association between circulating IL-6 concentration and brain infarct volume, stroke severity, or outcome up to 6 months [13–17]. Conversely, other studies have reported no association between serum IL-6 concentration and infarct volume or stroke severity at 3 months [4, 18]. Other markers of the acute phase response have also been implicated in the pathophysiology and outcome following ischaemic stroke [19–26]. However, very few studies have related the magnitude of the peripheral inflammatory response in the first week to measures of severity of ischaemic insult or clinical outcome.

We have recently reported the kinetics of peripheral inflammatory markers in ischaemic stroke patients prospectively recruited within 12 hours of symptom onset, compared to controls matched for age, sex and degree of atherosclerosis [27]. The aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between the magnitude of the peripheral inflammatory response, as determined by peak values of plasma IL-6 or other peripheral inflammatory markers (peak plasma C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), plasma cortisol concentration and aural temperature) in the first week of stroke, with either severity of ischaemic insult, or long-term outcome.

Subjects and methods

The study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee. Consecutive patients aged over 18 years presenting with a clinical diagnosis of acute stroke, with suspected symptom onset within the preceding 12 hours, were screened prospectively. Patients were excluded if the time of symptom onset could not be reliably determined from the patient or witness. Patients with rapid improvement of symptoms between onset and screening, or evidence of active malignancy, were also excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients recruited, or written assent from a relative. Clinical history, examination, medications and Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project (OCSP) classification [28] were recorded at baseline. Computed tomography (CT) brain scan (IGE CT Pace Plus 3rd generation scanner, IGE Medical Systems Ltd, Milwaukee, WI) was performed within 24 hours of admission to exclude patients with stroke mimic or primary intracerebral haemorrhage (PICH). Blood pressure, pulse rate and aural temperature (Braun Thermoscan LF20 digital thermometer) were recorded at all visits. At 3 and 12 months, additional medical history, changes in medication history and general clinical examination were also recorded. Infections were recorded prospectively during the study period wherever possible, using all available clinical information and investigation results. In the case of suspected infections preceding the index stroke, information was gathered from history and clinical records.

Blood sampling and determination of peripheral inflammatory markers

Venous blood was drawn by venepuncture at study entry, next day at 09:00, 24 hours (if presentation was not between 07:00 and 11:00) and 5 to 7 days. Blood was collected in tubes containing EDTA (Sarstedt, UK) for analysis of ESR using an automated Westergren method (Starrsed 3, Mechatronics, Holland; supplied by Vitech Scientific, UK) and total WBC count using the Coulter principle method (Beckman-Coulter GEN-S, Florida, USA). The remaining blood for plasma IL-6, CRP and cortisol analysis was transferred to heparinised tubes, stored in cooled gel packs for one hour, and centrifuged at 2000 g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Plasma was separated, frozen and stored at -70°C until analysis. Plasma IL-6 was measured using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), plasma CRP using a competitive, high-sensitivity ELISA, and plasma cortisol using a solid phase time-resolved fluroimmunoassay (DELFIA®, Perkin Elmer™ Life Sciences, manufactured by Wallac Oy, Finland) described in detail elsewhere [27].

Definition of peak values

For individual patients, the peak value for each peripheral inflammatory marker was defined as the maximum measured value between presentation and 5 to 7 days. Patients who died prior to 5 to 7 days, or for whom data were missing, were therefore not assigned a peak value and were excluded from further analysis.

Assessment of stroke severity and outcome

Stroke severity was assessed using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score [29] at presentation and 5 to 7 days. Functional status during the four weeks preceding the index stroke was recorded using the modified Rankin score (mRS) [30] and Barthel index (BI) [31] at presentation. Subsequent functional outcome was assessed using the mRS and BI at 3 and 12 months, derived either directly from evaluation of the patient or discussion with carers and relatives, or by telephone. Patients were contacted prior to the 3 and 12 month follow up periods for arrangement of hospital or home visits where necessary. All-cause mortality was recorded from death certificates and hospital records.

Measurement of CT brain infarct volume

A second CT brain scan for volumetric analysis was performed at 5 to 7 days, in order to minimise the "fogging" effect seen in the second to third weeks after ischaemic stroke [32]. Five to seven day CT brain scans and plasma sampling were performed on the same day, except in five cases where plasma was sampled, and CT scans performed, within 24 hours of each other.

The area of visible recent infarction on each digitised slice was traced manually with a cursor, the volume of infarction was automatically calculated by the scanner volumetry program based on the areas measured, slice thickness and number of slices. For each 5 to 7 day scan with visible recent infarction, the mean of five observers' (CJS, HCAE, CML and two consultant neuroradiologists; DGH and IWT) independent infarct volume measurement was determined.

Statistical analysis

Pre-determined primary analyses were the association between peak plasma IL-6 concentration in the first week of ischaemic stroke, with either CT brain infarct volume, or mRS at 3 months. Secondary analyses explored the relationships between (1) peak plasma IL-6 concentration with stroke severity, BI at 3 months or outcome at 12 months, and (2) other peripheral inflammatory markers in the first week of ischaemic stroke and stroke severity, CT brain infarct volume or clinical outcome.

For the pre-determined primary analyses, significance was set at the 0.05 level. Data from the large number of secondary analyses are descriptive only, and used for the purpose of hypothesis generation. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® for Windows, version 10. Categorical data were summarised as frequencies and percentages. Continuous data were summarised as median (minimum, maximum). Non-parametric analyses were used throughout as the inflammatory markers were not normally distributed, and outcome measures were ordinal scales. Use of non-parametric methods allowed extension of scoring for outcome scales to incorporate death as the "worst outcome" possible. This prevented bias from exclusion of patients who died during study follow up. The relationship between inflammatory markers and outcome measures was determined using Spearman rank correlation. The Kaplan-Meier technique and log-rank test were applied in analysis of survival for patients with values above and below the median of peak plasma IL-6 concentration.

Results

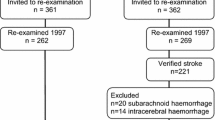

Thirty-seven patients with ischaemic stroke were recruited between April 2000 and January 2001. Baseline characteristics and medications for the 37 patients at entry are presented in Table 1. Median (minimum, maximum) time from onset of stroke symptoms to recruitment was 5 (1.5 to 11.75) hours. Stroke characteristics and outcome measures are presented in Table 2. The number of patients at each visit is outlined in Figure 1. Two patients had documented infections (both respiratory), and one, a proven myocardial infarction within the six weeks preceding their index stroke. A further 7 had definite infections (four respiratory, two urinary and one peripheral cannula site), within the first week after the index stroke. One other patient developed sepsis during the first week, with no focus identified. Three patients died prior to the 5 to 7 day assessment (including the patient with the preceding myocardial infarction) leaving 34 patients with peak values of plasma IL-6, CRP, cortisol and aural temperature for analysis. Peak WBC count values were available in 32, and peak ESR in 27 of these patients. Of the fourteen patients (38%) who died by 12 months, causes of death were certified as index stroke in eight, recurrent stroke in one, sepsis in three, pulmonary embolus in one, and left ventricular failure secondary to preceding myocardial infarction in another.

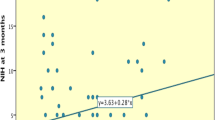

Peak plasma IL-6 concentration and outcome

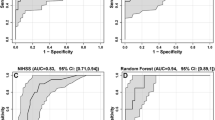

In the primary analyses, peak plasma IL-6 concentration correlated significantly with CT brain infarct volume and mRS at 3 months (Figure 2). Exclusion of patients with infection within the 6 weeks preceding, or one week following stroke did not materially affect these relationships (CT brain infarct volume: r = 0.62, p = 0.006; mRS: r = 0.62, p = 0.002). Peak plasma IL-6 concentration also correlated (p < 0.001) with stroke severity at 5 to 7 days (r = 0.66), BI at 3 months (r = -0.74), mRS at 12 months (r = 0.77) and BI at 12 months (r = -0.77). As above, exclusion of patients with infection did not materially alter these findings (stroke severity at 5 to 7 days: r = 0.54, p = 0.006; mRS at 12 months: r = 0.67, p = 0.001; BI at 3 months: r = -0.64, p = 0.001; BI at 12 months: r = -0.63, p = 0.003). As shown in Figure 3, peak plasma IL-6 concentration above the sample median (30.5 pg/ml) was associated with increased mortality at 12 months (p = 0.0011, log-rank test).

Peak plasma CRP, ESR, WBC count, plasma cortisol, aural temperature and outcome

Correlation coefficients are presented in Table 3. Strong associations were apparent for peak plasma CRP concentration and peak WBC count in particular, with weaker correlations for peak plasma cortisol concentration, ESR and aural temperature. Exclusion of the patients with infection did not materially alter these findings (data not shown).

Discussion

In the present study, we report that peak plasma IL-6 concentration in the first week of ischaemic stroke correlated significantly with CT brain infarct volume at 5 to 7 days, and clinical outcome at 3 months. Secondary analyses also demonstrated strong associations between peak plasma IL-6 and stroke severity, clinical outcome, or mortality at 12 months. In keeping with these findings, other peripheral markers of inflammation, including peak plasma CRP, WBC count, ESR or plasma cortisol, were associated with severity of stroke, CT brain infarct volume or clinical outcome.

We reasoned that a good estimate of the magnitude of the peripheral inflammatory response would be obtained by taking the peak value of measurements within the first 24 hours of stroke, or at the end of the first week. We accept that it is difficult to determine the true peak without continuous or multiple serial measurements. Furthermore, only patients with data at all timepoints, and those surviving to day 5 to 7 could be included in analysis of peak values, therefore excluding patients that died within the first week who may have had the most severe strokes. Previous studies have reported peak values of serum IL-6 within the first 10 days of stroke [13, 15, 18, 33], but only two related peak IL-6 to outcome measures, with neither defining primary analyses. Our data confirm the strong correlation between peak serum IL-6 with CT infarct volume or stroke severity [13, 15]. We have extended these findings by demonstrating, for the first time, strong correlations between peak plasma IL-6 with measures of clinical outcome at 3 and 12 months. Furthermore, to our knowledge, we are the first to report association between individual peak values of plasma CRP concentration, ESR or WBC count within the first week of ischaemic stroke, and CT brain infarct volume or outcome.

We did not exclude stroke patients with preceding or concurrent inflammatory conditions, as it may be argued that findings are more useful if applicable to a generalised population of patients, and that a systemic inflammatory response to infection might contribute to poor outcome. We may have underestimated the number of our patients with infection, as we did not apply predetermined criteria for defining, or investigating, infectious episodes. However, this also applies to previous studies of inflammation and stroke where patients with infection were said to have been excluded. Nevertheless, after performing post-hoc analysis of our patients, excluding those with inflammatory conditions in the six weeks preceding, or during the first week of index stroke, correlations between peak plasma IL-6, CRP or WBC count and outcome were only moderately reduced.

The question arises as to whether IL-6 might directly contribute to infarct pathogenesis, or is simply a marker of CNS, or indeed other, inflammatory injury. On the one hand, IL-6 has several pro-inflammatory effects [10, 34–37] which may contribute to the induction and evolution of early inflammatory injury in the brain and its vasculature. Furthermore, IL-6 is up-regulated by the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [38]. In experimental cerebral ischaemia, there is considerable evidence implicating IL-1β in cerebral injury [39], although TNF-α may have both deleterious and protective effects [40]. On the other hand, IL-6 also has neurotrophic [41], and anti-inflammatory effects [42] which may also be important after cerebral ischaemia.

An important consideration is whether peripheral markers of inflammation relate to outcome independent of stroke severity or brain infarct volume. IL-6 concentration independently predicts early neurological deterioration [14], and CRP concentration independently predicts survival, after ischaemic stroke [22, 24–26]. We could not use a multifactorial model to address whether peak plasma IL-6 concentration related to outcome independently of stroke severity or infarct size due to the limitation of our sample size and insufficient power.

Despite the ability of IL-6 to induce fever or activate the HPA axis, peak plasma IL-6 concentration only correlated weakly with peak aural temperature or peak plasma cortisol concentration (data not shown). Peak aural temperature correlated weakly with brain infarct volume, stroke severity or outcome, in contrast to previous studies [23, 43]. However, it is unclear from these previous reports how many patients received antipyretics in relation to measurements of temperature. In our study, a high proportion of stroke patients received aspirin (300 mg), paracetamol, or both, in the first week of stroke, which may have affected observed aural temperature readings. Peak plasma cortisol concentration correlated modestly with CT brain infarct volume, stroke severity or outcome, in agreement with previous studies [19, 44, 45].

Conclusion

We have demonstrated significant correlations between peak plasma IL-6 in the first week of ischaemic stroke with both brain infarct volume and outcome at 3 months. Secondary analyses supported the relationship between peripheral inflammatory markers and both the extent of tissue injury, and clinical outcome to 12 months. Peripheral inflammatory markers may provide useful prognostic information in patients with acute ischaemic stroke, and pharmacological modulation of the inflammatory response may provide the basis for novel acute neuroprotective therapies for use in patients with cerebral ischaemia.

References

del Zoppo G, Ginis I, Hallenbeck JM, Iadecola C, Wang X, Feuerstein GZ: Inflammation and stroke: putative role for cytokines, adhesion molecules and iNOS in brain response to ischemia. Brain Pathol. 2000, 10: 95-112.

Loddick SA, Turnbull AV, Rothwell NJ: Cerebral interleukin-6 is neuroprotective during permanent focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998, 18: 176-179. 10.1097/00004647-199802000-00008.

Clark WM, Rinker LG, Lessov NS, Hazel K, Eckenstein F: Time course of IL-6 expression in experimental CNS ischemia. Neurol Res. 1999, 21: 287-292.

Tarkowski E, Rosengren L, Blomstrand C, Wikkelsö C, Jensen C, Ekholm S, Tarkowski A: Early intrathecal production of interleukin-6 predicts the size of brain lesion in stroke. Stroke. 1995, 26: 1393-1398.

Matsuda S, Wen T-C, Morita F, Otsuka H, Igase K, Yoshimura H, Sakanaka M: Interleukin-6 prevents ischemia-induced learning disability and neuronal and synaptic loss in gerbils. Neurosci Lett. 1996, 204: 109-112. 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12340-5.

Clark WM, Rinker LG, Lessov NS, Hazel K, Hill JK, Stenzel-Poore M, Eckenstein F: Lack of interleukin-6 expression is not protective against focal central nervous system ischemia. Stroke. 2000, 31: 1715-1720.

Rothwell NJ, Hopkins SJ: Cytokines and the nervous system II: actions and mechanisms of action. Trends Neurosci. 1995, 18: 130-136. 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93890-A.

Grau AJ, Buggle F, Becher H, Zimmermann E, Spiel M, Fent T, Maiwald M, Werle E, Zorn M, Hengel H, Hacke W: Recent bacterial and viral infection is a risk factor for cerebrovascular ischemia: clinical and biochemical studies. Neurology. 1998, 50: 196-203.

Kammersgaard LP, Jørgensen HS, Reith J, Nakayama H, Houth JG, Weber UJ, Pederson PM, Olsen TS: Early infection and prognosis after acute stroke: the Copenhagen stroke study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001, 10: 217-221. 10.1053/jscd.2001.30366.

Ramadori G, Christ B: Cytokines and the hepatic acute-phase response. Semin Liver Dis. 1999, 19: 141-155.

Luheshi G, Rothwell N: Cytokines and fever. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1996, 109: 301-307.

Chrousos GP: Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N Eng J Med. 1995, 332: 1351-1362. 10.1056/NEJM199505183322008.

Fassbender K, Rossol S, Kammer T, Daffertshofer M, Wirth S, Dollman M, Hennerici M: Proinflammatory cytokines in serum of patients with acute cerebral ischemia: kinetics of secretion and relation to the extent of brain damage and outcome of disease. J Neurol Sci. 1994, 122: 135-139. 10.1016/0022-510X(94)90289-5.

Vila N, Castillo J, Dávalos A, Chamorro A: Proinflammatory cytokines and early neurological worsening in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2000, 31: 2325-2329.

Perini F, Morra M, Alecci M, Galloni E, Marchi M, Toso V: Temporal profile of serum anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory interleukins in acute ischemic stroke patients. Neurol Sci. 2001, 22: 289-296. 10.1007/s10072-001-8170-y.

Castellanos M, Castillo J, García MM, Leira R, Serena J, Chamorro A, Dávalos A: Inflammation-mediated damage in progressing lacunar infarctions: a potential therapeutic target. Stroke. 2002, 33: 982-987. 10.1161/hs0402.105339.

Acalovschi D, Wiest T, Hartmann M, Farahmi M, Mansmann U, Auffarth GU, Grau AJ, Green FR, Grond-Ginsbach C, Schwaninger M: Multiple levels of regulation of the interleukin-6 system in stroke. Stroke. 2003, 34: 1864-1870. 10.1161/01.STR.0000079815.38626.44.

Ferrarese C, Mascarucci P, Zoia C, Cavarretta R, Frigo M, Begni B, Sarinella F, Frattola L, De Simoni MG: Increased cytokine release from peripheral blood cells after acute stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999, 19: 1004-1009. 10.1097/00004647-199909000-00008.

Murros K, Fogelholm R, Kettunen S, Vuorela A-L: Serum cortisol and outcome of ischemic brain infarction. J Neurol Sci. 1993, 116: 12-17.

Chamorro A, Vila N, Ascaso C, Saiz A, Montalvo J, Alonso P, Tolosa E: Early prediction of stroke severity: role of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Stroke. 1995, 26: 573-576.

Czlonkowska A, Ryglewicz D, Lechowicz W: Basic analytical parameters as the predictive factors for 30-day case fatality rate in stroke. Acta Neurol Scand. 1997, 95: 121-124.

Muir KW, Weir CJ, Alwan W, Squire IB, Lees KR: C-reactive protein and outcome after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1999, 30: 981-985.

Hajat C, Hajat S, Sharma P: Effects of poststroke pyrexia on stroke outcome: a meta-analysis of studies in patients. Stroke. 2000, 31: 410-414.

Di Napoli M, Papa F, Bocola V: Prognostic influence of increased C-reactive protein and fibrinogen levels in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2001, 32: 133-138.

Di Napoli M, Papa F, Bocola V: C-reactive protein in ischemic stroke: an independent prognostic factor. Stroke. 2001, 32: 917-924.

Winbeck K, Poppert H, Etgen T, Conrad B, Sander D: Prognostic relevance of early serial C-reactive protein measurements after first ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2002, 33: 2459-2464. 10.1161/01.STR.0000029828.51413.82.

Emsley HCA, Smith CJ, Gavin CM, Georgiou RF, Vail A, Barberan EM, Hallenbeck JM, del Zoppo GJ, Rothwell NJ, Tyrrell PJ, Hopkins SJ: An early and sustained peripheral inflammatory response in acute ischaemic stroke: relationships with infection and atherosclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2003, 139: 93-101. 10.1016/S0165-5728(03)00134-6.

Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis M, Burn J, Warlow C: Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. 1991, 337: 1521-1526. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93206-O.

Lyden P, Brott T, Tilley B, Welch KMA, Mascha EJ, Levine S, Haley EC, Grotta J, Marler J, and the NINDS TPA Stroke Study Group: Improved reliability of the NIH Stroke Scale using video training. Stroke. 1994, 25: 2220-2226.

van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJA, van Gijn J: Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988, 19: 604-607.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW: Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965, 14: 61-65.

Skriver EB, Olsen TS: Transient disappearance of cerebral infarcts on CT scan, the so-called fogging effect. Neuroradiology. 1981, 22: 61-65.

Kim JS, Yoon SS, Kim YH, Ryu JS: Serial measurement of interleukin-6, transforming growth factor-β, and S-100 protein in patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 1996, 27: 1553-1557.

Ulich TR, del Castillo J, Guo K: In vivo hematologic effects of recombinant interleukin-6 on hematopoiesis and circulating numbers of RBCs and WBCs. Blood. 1989, 73: 108-110.

Biswas P, Delfanti F, Bernasconi S, Mengozzi M, Cota M, Polentarutti N, Mantovani A, Lazzarin A, Sozzani S, Poi G: Interleukin-6 induces monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and in the U937 cell line. Blood. 1998, 91: 258-265.

Brett FM, Mizisin AP, Powell HC, Campbell IL: Evolution of neuropathologic abnormalities associated with blood-brain barrier breakdown in transgenic mice expressing interleukin-6 in astrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995, 54: 766-775.

Johnson JL, Moore EE, Tamura DY, Zallen G, Biffl WL, Silliman CC: Interleukin-6 augments neutrophil cytotoxic potential via selective enhancement of elastase release. J Surg Res. 1998, 76: 91-94. 10.1006/jsre.1998.5295.

Shalaby MR, Waage A, Aarden L, Espevik T: Endotoxin, tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin 1 induce interleukin 6 production in vivo. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1989, 53: 488-498.

Allan SM, Rothwell NJ: Cytokines and acute neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001, 2: 734-744. 10.1038/35094583.

Hallenbeck JM: The many faces of tumor necrosis factor in stroke. Nat Med. 2002, 8: 1363-1368. 10.1038/nm1202-1363.

Gruol DL, Nelson TE: Physiological and pathological roles of interleukin-6 in the central nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. 1997, 15: 307-339.

Schindler R, Mancilla J, Endres S, Ghorbani R, Clark SC, Dinarello CA: Correlations and interactions in the production of interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in human blood mononuclear cells: IL-6 suppresses IL-1 and TNF. Blood. 1990, 75: 40-47.

Kammersgaard LP, Jørgensen HS, Rungby JA, Reith J, Nakayama H, Weber UJ, Houth J, Olsen TS: Admission body temperature predicts long-term mortality after acute stroke: the Copenhagen stroke study. Stroke. 2002, 33: 1759-1762. 10.1161/01.STR.0000019910.90280.F1.

O'Neill PA, Davies I, Fullerton KJ, Bennett D: Stress hormone and blood glucose response following acute stroke in the elderly. Stroke. 1991, 22: 842-847.

Fassbender K, Schmidt R, Möβner R, Daffertshofer M, Hennerici M: Pattern of activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in acute stroke. Relation to acute confusional state, extent of brain damage, and clinical outcome. Stroke. 1994, 25: 1105-1108.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/4/2/prepub

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Mrs. Sylvia Scarth, Ms. Karen Illingworth and Mr. Noel Kelso, NWIRC, Hope Hospital, for their assistance with laboratory assessments and assays; and Ms. Paula Beech, stroke research nurse, Hope Hospital, for her assistance with the clinical assessments. We are also grateful to Dr. David G. Hughes (DGH) and Dr. Ian W. Turnbull (IWT), consultant neuroradiologists, Hope Hospital, for their contribution to the brain infarct volume measurements.

This study was funded by a grant from Research into Ageing, provided by the UK Community Fund, and supported by Salford Royal Hospitals NHS Trust Research and Development Directorate. CJS, HCAE and RFG are funded by Research into Ageing; EMB is funded by North Manchester Healthcare NHS Trust; CMG, AV and SJH are funded by Salford Royal Hospitals NHS Trust. GJDZ is supported by grants NS26945 and NS38710 of the NIH; JMH is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; NJR is supported by the Medical Research Council; PJT is funded by the University of Manchester, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

None declared.

Authors' Contributions

CJS carried out clinical assessments, data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. HCAE, CMG, RFG and EMB carried out clinical assessments, data collection and contributed to manuscript preparation. AV provided statistical expertise in the design of the study and analysis of data. NJR, PJT and SJH conceived of the study, protocol design, and participated in the preparation of the manuscript. SJH supervised the laboratory studies and designed the protocol for venous blood processing and assays. GJdZ and JMH assisted in the design of the study, data analysis and manuscript preparation.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-4-5.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, C.J., Emsley, H.C., Gavin, C.M. et al. Peak plasma interleukin-6 and other peripheral markers of inflammation in the first week of ischaemic stroke correlate with brain infarct volume, stroke severity and long-term outcome. BMC Neurol 4, 2 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-4-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-4-2