Abstract

Background

Albuminuria marks renal disease and cardiovascular risk. It was estimated to contribute 75% of the risk of all-cause natural death in one Aboriginal group. The urine albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) is commonly used as an index of albuminuria. This study aims to examine the associations between demographic factors, anthropometric index, blood pressure, lipid-protein measurements and other biomarkers and albuminuria in a cross-sectional study in a high-risk Australian Aboriginal population. The models will be evaluated for albuminuria at or above the microalbuminuria threshold, and at or above the “overt albuminuria” threshold with the potential to distinguish associations they have in common and those that differ.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of 598 adults aged 18–76 years. All participants were grouped into quartiles by age. Logistic regression models were used to explore the correlates of ACR categories.

Results

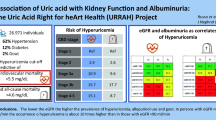

The significant correlates were systolic blood pressure (SBP), C-reactive protein (CRP), uric acid, diabetes, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) (marginally significant, p = 0.054) and serum albumin (negative association) for ACR 17+ (mg/g) for men and 25+ for women. Independent correlates were SBP, uric acid, diabetes, total cholesterol, alanine amino transferase (ALT), Cystatin C and serum albumin (negative association) for overt albuminuria; and SBP, CRP and serum albumin only for microalbuminuria.

Conclusions

This is the most detailed modelling of pathologic albuminuria in this setting to date. The somewhat variable association with risk factors suggests that microalbuminuria and overt albuminuria might reflect different as well as shared phenomena.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Australian Aboriginal people, especially those living in remote areas, have greater rates of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1–3] compared with other Australian ethnicities. The incidence of patients with ESRD starting renal replacement therapy in remote regions is up to 30 times the national incidence for all Australians [4]. The urine albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) is commonly used as an index of albuminuria. In a study of one high-risk community, albuminuria, which was pervasive, and much more common than hypertension and diabetes and, not only marked all future risk of renal failure, the treatment of which is very costly, but also predicted cardiovascular and nonrenal noncardiovascular deaths [2, 5–8]. Albuminuria was estimated to contribute 75% of the risk of all-cause natural death during a short longitudinal period of observation [1]. Recently the authors reported that albuminuria was still a remarkable predictor for all-cause natural death over an average of 14 years follow-up interval in an Aboriginal community [9]. Thus albuminuria represents a potential target for intervention [10]. A number of variables were measured in a cross-sectional survey on a high-risk Australian Aboriginal population. Thus this study aims to explore the associations between demographic factors, anthropometric index, blood pressure, lipid-protein measurements and other biomarkers and albuminuria. The models will be evaluated for albuminuria at or above the microalbuminuria threshold, and at or above the “overt albuminuria” threshold with the potential to distinguish associations they have in common and those that differ.

Methods

Study population

Participants were recruited from an Australian Aboriginal community living in a remote area in Northern Territory of Australia between 1992 and 1998 as part of a screening program for chronic disease. Participants aged 18 years and over were included in the analysis.

Measurements of baseline characteristics

Urinary albumin concentrations were measured simultaneously by both nephelometric and high-performance liquid chromatography techniques on random urine sample. When we examined over a Z-score continuum of their values, they were identical in defining clinical profiles and predicting deaths [11]. Thus the results here are based on the concentration measured using Beckman immunoassay on a Dade Behring Prospect Analyser, with reagents and calibrators supplied by Dade Behring Diagnostics (Sydney, Australia). Urinary creatinine concentration was measured using an alkaline picrate method (Olympus AU800 Autoanalyzer; interassay CV 2%). Simple anthropometric indices, blood pressure, glucose, lipoprotein profiles, C-reactive protein (CRP), uric acid, serum albumin, cystatin C, serum gamma glutammyl transferase (GGT) and alanine amino transferase (ALT) were also measured. The sex-specific cut points of ACR were applied to categorise participants as, normal (ACR < 17 mg/g for men; <25 for women), microalbuminuria (ACR 17–249 for men; 25–354 for women) and overt albuminuria (ACR ≥ 250 for men; ≥355 for women) [12].

Diabetes refers to those known to be diabetic before the baseline survey or who had fasting glucose ≥126 or 2-hr glucose ≥199.8 mg/dl or “random glucose” ≥199.8 mg/dl. Smoking and alcohol drinking were self-reported. All participants were regrouped into quartiles by age. Continuous variables that are not normal distributed were logarithm-transferred prior to analysis.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression modellings for ACR categories including all potential predictors available in this study were applied. All analyses were undertaken using Stata 11.1 (Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11.1, College Station. TX: StatCorp LP, 2009).

The informed consent for the original population screening program was obtained prior to the survey. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Menzies School of Health Research and Territory Health Services and The Behavioural and Social Science Ethical Review Committee of the University of Queensland.

Results

Characteristics of participants

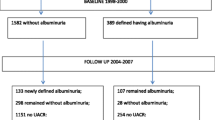

At the baseline survey, ACR was measured in a total of 755 participants aged 18 years and over, and 598 of them with a complete set of risk factor measurements were included in the analysis. Age ranged from 18 to 76 years, with a mean of 34 years. The geometric mean, (95% CI) ACR value was 32.6 mg/g (27.5-38.7).

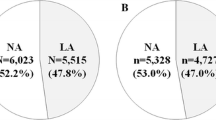

Proportion of participants with normal ACR (using sex-specific cut-off points) was 47.8% while microalbuminuria and overt albuminuria were present in 40.8% and 19.2%, respectively.

BMI, SBP, cholesterol, triglycerides, CRP, cystatin c, serum GGT and diabetes prevalence increased with the age while HDL and serum albumin were opposite (Table 1). Uric acid and serum ALT were not associated with age. The proportion of smokers was significantly high in this community ranged from 67-78% (Table 1).

Logistic regression

In the logistic regression modelling, SBP, serum uric acid, CRP and diabetes were significantly associated with albuminuria (Table 2) and it was marginally significant for GGT (p = 0.054) while there was significantly inverse relationship between serum albumin and albuminuria (Table 2). Table 3 shows that the independent correlates of microalbuminuria were SBP, CRP, serum albumin (inverse association) and uric acid (marginally significantly, p = 0.068) while the independent predictors of overt albuminuria were total cholesterol, SBP, uric acid, cystatin c, diabetes, serum albumin and ALT (both were negative association).

Figures 1 and 2 shows the predicted amplification of albuminuria and overt albuminuria produced by the simultaneous presence of risk factors identified as independent predictors in the final multivariate model. The predictors were categorical variables derived from each continuous variable using sex-specific median value as the cut-off point. There were substantial rates of elevated ACR (≥17 mg/g for men; ≥25 for women) with increasing age even in the absence of other factors which had independent correlations with ACR. However, the probability of overt albuminuria with increasing age alone was more modest.

Discussion

In this high risk Aboriginal population, SBP, serum albumin (inverse association), uric acid, CRP, diabetes were significantly associated with albuminuria (p value for GGT was 0.054).

SBP, serum albumin, CRP were significantly associated with microalbuminuria (p value for uric acid was 0.068) while additional risk factors including total cholesterol, ALT, cystatin C and diabetes were significantly associated with overt albuminuria. The shared and the different risk factors for these conditions, traditionally considered to be stages of albuminuria over a continuum, suggest that microalbuminuria and overt albuminuria might reflect different as well as shared phenomena. Different or inconsistent associations of albuminuria with abdominal obesity have been reported in some other studies [13–16] but no significant evidence in this study. Macroalbuminuria was independently associated with hypertension, diabetes and abdominal obesity in Central Australian Aboriginal communities [13].

A close link between high blood pressure and microalbuminuria has been reported by others. In the relationship, higher blood pressure might cause microalbuminuria by increasing glomerular filtration pressure and subsequent renal damage, [17] and adequate control of SBP was associated with low risk for development of microalbuminuria [18]. In addition, the magnitude of urinary albumin excretion determines the severity of BP elevation, [19, 20] and there exist heritability and genetic associations between increased urinary albumin excretion and BP in some ethnic groups [21]. CRP, a member of the class of acute phase reactants, is regarded as a sensitive marker of inflammation and was reported as an important contributor to albuminuria (but not an independent predictor for overt albuminuria) in this study. CRP levels are affected significantly by an individual’s genetic makeup and life style [22, 23]. People who smoke, have elevated BP, who are overweight or have less physical activity, tend to have higher level of CRP [24, 25]. CRP has been reported to be a novel cardiovascular risk factor, [26] and we have reported that it is independently associated with the development of diabetes in this Aboriginal cohort [27]. A significant association between CRP level and microabuminuria has also been reported in some other epidemiological studies [26, 28–30]. The relationship might indicate that chronic inflammation is a potential mediator between microalbuminuria and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [28].

A significant inverse association was found between serum albumin and albuminuria, even after adjusting for a number of confounding factors in this study. Albumin is the major protein produced only in the liver. Lower serum albumin may also indicate some conditions other than liver dysfunction. Serum albumin levels are lowered by infection and inflammation, and they decrease as a consequence of acute phase inflammatory reactions, [31] in which increased cytokines switch protein synthesis in the liver from albumin to other phase proteins, and serum albumin falls [32]. Serum albumin levels were also inversely related to age in this study, and, ironically, have been described as higher in smokers than non-smokers [33, 34]. Thus, further evaluation in longitudinal studies is required to determine if the inverse relation between serum albumin and albuminuria is causal.

Other reports describe that lower levels of pathologic albuminuria are significantly associated with cigarette smoking and heavy alcohol consumption [35]. However there was no significant association between smoking and albuminuria in our study. Serum GGT has long been used as a liver function test and a marker of excessive alcohol use; [36, 37] about 35% of women and 87% of men in this cohort were drinkers, with of men with most males drinking to excess [38]. Associations between high GGT and CVD, [31, 32] type-2 diabetes [33] and hypertension [38] have been reported. Our findings support the observation that GGT might also be a novel predictor of chronic kidney disease [39, 40]. The possible mechanism of such associations is that oxidative stress depletes glutathione stores which leads to a compensatory increase in GGT, [41, 42] or more free radicals might contribute to high levels of GGT [43, 44]. There is also evidence that high GGT in certain people is genetically based [45, 46]. As serum GGT is easy and cheap to measure, it might have important practical implications on predicting albuminuria and other chronic diseases in Aboriginal communities.

Strengths of this study include the fact that over 80% adult population in this remote Aboriginal community participated. In addition, as Aboriginal people have significantly higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD), an easy implemented risk prediction model based on routinely obtained laboratory test is important [47]. In this study, all correlates of albuminuria were derived from the available clinical information, and important metabolic markers such as Cystatin C, uric acid and serum albumin were included in the data analysis. Both the albumin and the CRP have helped shed light on the possibly different associations depending on the level of albuminuria. Third, strength is that we now know that these relationships will apply whether ACR is measured by immunoassay rather than HPLC, as we have proven that both are identical in defining clinical profiles and predicting deaths in this community [11].

There were also some limitations in this study. First, the risk predictors in this study were derived from cross-sectional data only, causal association might not exist or the correlates might not be the same in future forecasting. In fact, some correlates are probably markers of the CKD and CVD risk state rather than causal. A 14–16 year longitudinal study in this community is now under analysis and one of reports revealed that albuminuria was still a significant predictor of all-cause natural death after a 14-year interval in this Aboriginal community. However more longitudinal outcomes would shed further light on this issue. Second, with inclusion of new markers, the numbers went down (from 755 down to 598). Those omitted were slightly older (37 yrs vs. 33 yrs), with higher DBP level (78 mmHg vs. 74 mmHg) and higher prevalence of diabetes (16% vs. 6%) than those included. It indicates that this study may underestimate the strength of correlates to ACR in this community. Third, random rather than 24-h urine ACR value was used to define albuminuria in this study. However, the spot ACR is a validated screening test for microalbuminuria and has been used in this setting for 13 years, with widely published data [13]. Finally, findings from a remote community in the Northern Territory of Australia might not be generalizable to other populations. However, most of the significant correlates in our studies have been demonstrated in other settings [7, 48–51].

Conclusions

This is the most detailed modeling of pathologic albuminuria in this setting to date. In this study, SBP, CRP, lower serum albumin, uric acid, GGT and diabetes were significantly associated with albuminuria in the Aboriginal population. The somewhat variable association with risk factors suggests that microalbuminuria and overt albuminuria might reflect different as well as shared phenomena.

Authors’ information

ZMW - Ph.D, research fellow/epidemiologist at Centre for Chronic Disease, School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Australia.

W H - FRACP, Professor, Director at Centre for Chronic Disease, School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Australia.

ZQW – PhD, Associate Professor, deputy Director at Centre for Chronic Disease, School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, Australia.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

Urinary albumin to creatinine ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- GGT:

-

High gamma-glutamyl transferase

- CRP:

-

C- reactive protein (CRP)

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- ALT:

-

Alanine amino transferase

- HPLC:

-

High-performance Liquid chromatography

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease.

References

Spencer J, Silva D, Hoy W: An epidemic of renal failure among Australian aboriginal. Med J Aust. 1998, 168: 537-541.

Cunningham J, Condon JR: Premature mortality in aboriginal adults in the Northern Territory. Med J Aust. 1996, 165: 309-312.

Veroni M, Gracey M, Rouse I: Patterns of mortality in Western Australian aboriginals, 1983–89. Int J Epidemiol. 1994, 23: 73-81. 10.1093/ije/23.1.73.

Cass A, Cunningham J, Wang Z, Hoy W: Regional variation in the incidence of end-stage renal disease in Indigenous Australians. Med J Aust. 2001, 175: 24-27.

Wirta O, Pasternack A, Mustonen J, Laippala P: Renal and cardiovascular predictors of 9-year total and sudden cardiac mortality in non-insulin-independent diabetic subjects. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997, 12: 2612-2617. 10.1093/ndt/12.12.2612.

Hoy WE, Wang Z, Baker PRA, Kelly AM: Reduction in natural death and renal failure from a systematic screening and treatment program in an Australian aboriginal community. Kidney Int. 2003, 63 (Suppl 83): S66-S73.

Hoy W, McDonald SP: Albuminuria: marker or target in Indigenous populations. Kidney Int. 2004, 66 (Suppl 92): S25-S31.

Hoy WE: Renal disease in aboriginal Australians. Med J Aust. 1996, 165: 126-127.

Wang Z, Hoy WE: The predictive value of albuminuria for renal and nonrenal natural deaths over 14 years follow-up in a remote aboriginal community. Clin Kidney J. 2012, 5: 519-525. 10.1093/ckj/sfs125.

McDonald SP, Wang Z, Hoy WE: Physical and biochemical predictors of death in an Australian aboriginal cohort. Clin Expl Pharmacol P. 1999, 26: 618-621. 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03104.x.

Wang Z, Hoy W, Nicol JL, Su Q, Atkins R, Polkinghome KR: Predictive value of nephelometric and high-performance liquid chromatography assays of urine albumin for mortality in a high –risk aboriginal population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008, 52: 672-682. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.007.

Warram JH, Gearin G, Laffel L, Krolewski AS: Effect of duration of type I diabetes on the prevalence of stages of diabetic nephropathy defined by urinary albumin/creatinine ratio. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996, 7: 930-937.

Rowley KG, Iser DM, Best J, O’Dea K, Leonard D, McDermitt R: Albuminuria in Australian aboriginal people: prevalence and associations with components of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetologia. 2000, 43: 1397-1403. 10.1007/s001250051545.

Jager A, Kostense PJ, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Bouter LM, Stehouwer CDA: Microalbuminuria is strongly associated with NIDDM and hypertension, but not with the insulin resistance syndrome: the Hoorn study. Diabetologia. 1998, 41: 694-700. 10.1007/s001250050970.

Goetz FC, Jacobs DR, Chavers B, Roel J, Yelle M, Sprafka JM: Risk factors for kidney damage in the adult population of Wadena, Minnesota. Am J Epidemiol. 1997, 145: 91-102. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009091.

Smulders YM, Rakic M, Stehouwer CDA, Weijers RN, Slaats EH, Silberbusch J: Determinants of progression of microalbuminuria in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1997, 20: 999-1005. 10.2337/diacare.20.6.999.

Koroshi A: Microalbuminuria, is it so important?. Hippokratia. 2007, 11: 105-107.

Glassock RJ: Prevention of microalbuminuria in type-2 diabetes: millimetres or milligrams. J am Soc Nephrol. 2006, 17: 3276-3278. 10.1681/ASN.2006101131.

Hodge AM, Dowse GK, Zimmet PZ: Microalbuminuria, cardiovascular risk factors, and insulin resistance in two populations with a high risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1996, 13: 441-449. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199605)13:5<441::AID-DIA99>3.0.CO;2-J.

Konen JC, Summerson JH, Bell RA, Curtis LG: Racial differences in symptoms and complications in adults with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Ethn Health. 1999, 4: 39-49. 10.1080/13557859998182.

Guo X, Cui J, Wagenknecht LE, Norris JM, Haffner SM, Darwin C, Jinagouda S, Rotter JI, Saad MF: Cosegragation of albuminuria and blood pressure: the InsulinResistance Atherosclerosis (IRAS) family study. Am J Hypertens. 2005, 18: 823-827. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.01.022.

Li SH, Szmitko PE, Weisel RD, Wang CH, Fedak PWM, Li RK, Mickle DAG, Verma S: C-reactive protein upregulates complement-inhibitory factors in endothelial cells. Circulation. 2004, 109: 833-836. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000117087.27524.0E.

Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Buring J, Ridker PM: C-reactive protein levels among women of various ethnic groups living in the United Status (from the Women’s Health Study). Am J Cardiol. 2004, 93: 1238-1242. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.067.

Greenfield JR, Samaras K, Jenkins AB, Kelly PJ, Spector TD, Gallimore JR, Pepys MB, Campbell LV: Obesity is an important determinant of baseline serum C-reactive protein concentration in monozygotic twins, independent of genetic influences. Circulation. 2004, 109: 3022-3028. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130640.77501.79.

Chien KL, Hsu HC, Chen MF, Lee YT: Association of C-reactive protein, smoking and metabolic syndrome among the health check-up population. Acta Cardio Sin. 2005, 21: 98-104.

Nakamura M, Onoda T, Itai K, Ohsawa M, Satou K, Sakai T, Segawa T, Sasaki J, Tonari Y, Hiramori K, Okayama A: Association between serum c-reactive protein levels and microalbuminuria: a population-based cross-sectional study in northern Iwate, Japan. Internal Med. 2004, 43: 919-925. 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.919.

Wang Z, Hoy WE: C- reactive protein and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in aboriginal Australians. Diabetes Res Clin Pr. 2007, 76: 37-43. 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.07.018.

Festa A, D’agostino R, Howard G, Mykkanen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM: Inflammation and microalbuminuria in nondiabetic and type 2 diabetic subjects: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Kidney Int. 2000, 58: 1703-1710. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00331.x.

Stuveling EM, Bakker SJL, Hillege HL, Burgeruhof JGM, Jone PED, Gans ROB, De ZD: C-reactive protein modifies the relationship between blood pressure and microalbuminuria. Hypertension. 2004, 43: 791-796. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000120125.08867.42.

Tsioufis C, Dimitriadis K, Chatzis D, Vasiliadou C, Tousoulis D, Papademstriou V, Toutouzas P, Stefanadis C, Kallikazaros I: Relation of microalbuminuria to adiponectin and augmented C-reactive protein levels in men with essential hypertension. Am J Cardio. 2005, 96: 946-951. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.05.052.

Jousilahti P, Rastenyte D, Tuomilehto J: Serum gamma-glutamyl transferase, self-reported alcohol drinking and the risk of stroke. Stroke. 2000, 31: 1851-1855. 10.1161/01.STR.31.8.1851.

Lee DH, Silventoinen K, Hu G, Jacobs DR, Jousilahti P, Sundvall J, Tuomilehto J: Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase predicts non-fatal myocardial infarction and fatal coronary heart disease among 28, 838 middle-aged men and women. Eur Heart J. 2006, 27: 2170-2176. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl086.

Meisinger C, Lowel H, Heier M, Schneider A, Thorand B: Serum gamma- glutamyltransferase and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in men and women from the general population. J Intern Med. 2005, 258: 527-535. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01572.x.

Lee DH, Jacobs DR, Gross M, Kiefe CI, Roseman J, Lewis CE, Steffes M: Gamma-glutamyltransferase is a predictor of incident diabetes and hypertension: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Clin Chem. 2003, 49: 1358-1366. 10.1373/49.8.1358.

Lee DH, Jacobs DR, Gross M, Steffes M: Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase was differently associated with microalbuminuria by status of hypertension or diabetes: the coronary artery risk sevelopment in young adults (CARDIA) study. Clin Chem. 2005, 51: 1185-1191. 10.1373/clinchem.2004.045872.

Hoy WE, Wang Z, VanBuynder P, Backer PRA, McDonald SM, Mathews JD: The natural history of renal disease in Australian aborigines: part 2 albuminuria predicts natural death and renal failure. Kidney Int. 2001, 60: 249-256. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00793.x.

Conlgrave KM, Saunders JB, Reznik RB, Whitfield JB: Prediction of alcohol-related ham by laboratory test results. Clin Chem. 1993, 39: 2266-2270.

Hoy WE, Mathews JD, McCredie DA, Pugsley DJ, Havhurst BG, Rees M, Kile E, Walker KA, Wang Z: The multidimensional nature of renal disease: rates and associations of albuminuria in an Australian aboriginal community. Kidney Int. 1998, 54: 1296-1304. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00099.x.

Conigrave KM, Degenhardt LJ, Whitefield JB, Saunders JB, Helander A, Tabakoff B: CDT, GGT, and AST as markers of alcohol use: the WHO/ISBRA collaborative project. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002, 26: 332-339. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02542.x.

Whitfield JB: Serum -glutamyltransferase and risk of disease. Clin Chem. 2007, 1: 1-2.

Whitfield JB: Gamma glutamyl transferase. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2001, 38: 263-355. 10.1080/20014091084227.

Lee DH, Blomhoff R, Jacobs DR: Is serum gamma glutamyltransferase a marker of oxidative stress?. Free Radic Res. 2004, 38: 535-539. 10.1080/10715760410001694026.

Paolicchi A, Tongiani R, Tonarelli P, Comporti M, Pompella A: Gamma- glutamyl transpeptidase-dependent lipid peroxidation in isolated hepatocytes and HepG2 hepatoma cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997, 22: 853-860. 10.1016/S0891-5849(96)00422-4.

Drozdz R, Parmentier C, Hachad H, Leroy P, Siest G, Wellman M: Glutamyltransferase dependent generation of reactive oxygen species from a glutathione/transferrin system. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998, 25: 786-792. 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00127-0.

Bathum L, Petersen HC, Rosholm JU, Hyltoft PP, Vaupel J, Christensen K: Evidence for a substantial genetic influence on biochemical liver function tests: results from a population-based Danish twin study. Clin Chem. 2001, 47: 81-87.

Whitfield JB, Zhu G, Nestler JE, Heath AC, Martin NG: Genetic covariation between serum gamma-glutamyltransferase activity and cardiovascular risk factors. Clin Chem. 2002, 48: 1426-1431.

Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, Tighiouart H, Djurdjev O, Naimark D, Levin A, Levey AS: A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011, 305: 1553-1559. 10.1001/jama.2011.451.

Huo L, Xu M, Li R, Dai M, Wang JG, Ning G, Li XY: Prevalence and prevalence of microalbuminuria in persons with various glucose tolerance levels. ZhongHua YiXue Za Zhi. 2007, 87: 2537-2540.

Anvari MS, Boroumand MA, Pourgholi L, Sheikhfathollahi M, Rouhzendeh M, Rabbani S, Goodarzynejad H: Potential link of microalbuminuria with metabolic syndrome in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Arch Med Res. 2009, 40: 399-405. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2009.06.011.

Agrawal V, Vanhecke TE, Rai B, Franklin BA, Sangal RB, McCullough PA: Albuminuria and renal function in obese adults evaluated for obstructive sleep apnea. Nephron Clin Prac. 2009, 113: c140-c147. 10.1159/000232594.

Prasad GV, Bandukwala F, Huang M, Zaltman JS: Microalbuminuria post-renal transplantation: relation to cardiovascular risk factors and C-reactive protein. Clin Transplant. 2009, 23: 313-320. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00913.x.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/14/176/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the residents of the participating community, councils, health services, and many other people who assisted with field work. Data were collected by the renal research team at the Menzies School of Health Research.

Darwin, NT. The funding for this study was provided by grants from the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (No. 921134, 951342, and 320860) and from Territory Health Services, Kidney Health Australia.

Rio Tinto, the Colonial Foundation of Australia, Janssen Cilag, and Amgen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZMW - Analysis of data, drafting the article; revising the article, final approval of the version to be published. WH – Design and conduct of field work; Accrual of baselineine and longitudinal data; Conception and interpretation of data; revising the article; providing intellectual content of critical importance to the work described and final approval of the version to be published. ZQW - Revising the article; providing intellectual content of critical importance to the work described and final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Hoy, W.E. & Wang, Z. The correlates of urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) in a high risk Australian aboriginal community. BMC Nephrol 14, 176 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-14-176

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-14-176