Abstract

Background

The Ser358Leu mutation in TMEM43, encoding an inner nuclear membrane protein, has been implicated in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). The pathogenetic mechanisms of this mutation are poorly understood.

Methods

To determine the frequency of TMEM43 mutations as a cause of ARVC, we screened 11 ARVC families for mutations in TMEM43 and five desmosomal genes previously implicated in the disease. Functional studies were performed in COS-7 cells transfected with wildtype, mutant, and 1:2 wildtype:mutant TMEM43 to determine the effect of the Ser358Leu mutation on the stability and cellular localization of TMEM43 and other nuclear envelope and desmosomal proteins, assessed by solubility assays and immunofluorescence imaging. mRNA expression was assessed of genes potentially affected by dysfunction of the nuclear lamina.

Results

Three novel mutations in previously documented desmosomal genes, but no mutations in TMEM43, were identified. COS-7 cells transfected with mutant TMEM43 exhibited no change in desmosomal stability. Stability and nuclear membrane localization of mutant TMEM43 and of lamin B and emerin were normal. Mutant TMEM43 did not alter the expression of genes located on chromosome 13, previously implicated in nuclear envelope protein mutations leading to skeletal muscular dystrophies.

Conclusions

Mutant TMEM43 exhibits normal cellular localization and does not disrupt integrity and localization of other nuclear envelope and desmosomal proteins. The pathogenetic role of TMEM43 mutations in ARVC remains uncertain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is an inherited disorder characterized by replacement of cardiomyocytes by adipose and fibrous tissue, primarily in the right ventricle (RV). This disruption can result in RV dysfunction, arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. In the United States, 17% of sudden death victims between the ages of 20 and 40 years had ARVC. A large number of cases are unrecognized because clinical tests are relatively insensitive to in vivo detection of functional and structural changes in the RV [1, 2]. In approximately 40% of patients, mutations have been identified in genes encoding constituent proteins of cardiac desmosomes, namely, desmocollin-2 (DSC2), desmoglein-2 (DSG2), desmoplakin (DSP), junctional plakoglobin (JUP), and plakophilin-2 (PKP2)[3]. Mutations can lead to instability of other desmosomal proteins, resulting in their translocation from the cell membrane to the cytoplasm [4, 5].

We first mapped by genetic linkage analysis a large family with ARVC to a 9.3 cM region on chromosome 3p23, known as locus ARVC5 [6]. Recently, Merner and colleagues identified a c.1073 C > T mutation, leading to a p.Ser358Leu substitution, in a highly conserved region of transmembrane protein 43 (TMEM43) at this locus in the same family [7]. TMEM43, also known as LUMA, is a highly conserved inner nuclear membrane (INM) protein. It has been suggested that TMEM43 can cause pathological changes in the INM by affecting other protein complexes in it [8]. Furthermore, immunostaining of cardiac tissue from subjects with TMEM43 mutations indicated reduced expression of TMEM43 and plakoglobin, with TMEM43 showing localization at the sarcolemma [9]. However, little is known about function of TMEM43 and the mechanism by which mutations cause ARVC.

The overall goal of this study was to investigate the mechanisms by which mutations in TMEM43 may lead to ARVC. Given the novelty of the TMEM43 mutation in the context of previously reported mutations that were primarily in genes encoding desmosomal proteins, we first sought to determine the prevalence of mutations in TMEM43 relative to five desmosomal genes, namely, DSC2, DSG2, DSP, JUP, PKP2, in 11 ARVC probands. We found three novel mutations in different desmosomal genes, however, TMEM43 mutations were absent in these probands. Next, since common mechanisms often underlie each cardiomyopathy even in the setting of genetic heterogeneity, we conducted in vitro studies to determine whether the functional abnormalities caused by the rare TMEM43 S358L parallel those found in the setting of desmosomal mutations. COS-7 cells were transfected with either wildtype or mutant TMEM43, or co-transfected with both. Our studies showed that mutant TMEM43 protein did not disrupt interactions among desmosomal and nuclear envelope proteins, and did not lead to altered cellular localization of itself or of desmosomal and nuclear envelope proteins. Furthermore, mutant TMEM43 did not alter the expression of genes as observed in the cardiomyopathy caused by mutations in the nuclear membrane-associated protein, lamin A/C. Therefore, the role of the TMEM43 Ser358Leu mutation in ARVC remains uncertain.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 11 families with ARVC were recruited by the University of Pittsburgh Cardiovascular Genetics Center and the Harvard Medical School Department of Genetics, in accordance with protocols approved by their respective Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Clinical diagnosis of ARVC was based on the recently modified criteria originally proposed by the International Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the International Society and Federation of Cardiology [10]. Demographic and clinical data on probands and affected family members in whom a mutation was identified are shown in Table 1.

Genetic mutation screening

TMEM43, DSC2, DSG2, DSP, JUP and PKP2 were screened for mutations in all probands, followed by confirmation of any potential mutation in other available family members. Primers were designed using the Primer3 utility http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/. Each identified mutation was screened in 150 unrelated and unaffected control individuals to confirm its absence in normal population. Point mutations were detected by PCR amplification of exons, followed by direct sequencing (ABI). Identified mutations were analyzed for pathogenicity by using (1) protein prediction algorithms PolyPhen http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph/, SIFT http://sift.jcvi.org/, MUpro http://www.ics.uci.edu/~baldig/mutation.html and PMut http://mmb2.pcb.ub.es:8080/PMut/, (2) evolutionary conservation among species using ClustalW analysis, and (3) localization within a functionally important domain.

Construction of wildtype and mutant TMEM43expression vectors

Wildtype TMEM43

RNA was extracted from normal human heart tissue as described elsewhere [11]. cDNA for TMEM43 was synthesized using SuperScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The sequence was verified by direct sequencing. The resulting fragment was cloned into the pcDNA3.1/NT-GFP-topo eukaryotic expression vector (Invitrogen), which tags the expressed protein with GFP. Cloning and transformation into chemically competent E. coli cells was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was isolated using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) and quantified on a UV spectrophotometer. The sequence was verified by direct sequencing.

Ser358Leu mutant TMEM43

The QuickChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) was used to introduce the Ser358Leu mutation into the wildtype TMEM43 expression vector. Mutagenic primers were designed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was isolated as described above and presence of the Ser358Leu mutation was verified by direct sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection

COS-7 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin, and penicillin G at concentrations of 100 μg/ml each, and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Briefly, cells were grown overnight in supplemented DMEM medium and transfected in serum free medium with wildtype plasmid, mutant plasmid, or wildtype and mutant plasmid (at ratios of 1:1 and 1:2) for 6-8 hours. The medium in the plates was then replaced by supplemented DMEM. Cells were harvested five days following transfection.

Assessment of protein stability by solubility assays

Previous studies have suggested that disruption of cell-cell adhesion because of desmosomal dysfunction is a major mechanism of ARVC. Structural instability of desmosomes leads to localization of constituent proteins in the cytoplasmic instead of the cell membrane fraction following centrifugation in the presence of nondenaturing detergents such as Triton X-100 [5, 12]. We assessed the effect of mutant Ser358Leu TMEM43 on solubility patterns of four desmosomal proteins (desmocollin-2, desmoglein-2, desmoplakin, and junctional plakoglobin) and the cellular distribution of three nuclear envelope proteins (TMEM43, lamin B and emerin).

Solubility of desmosomal proteins

To evaluate the pathogenetic effect of mutant TMEM43 on desmosomal proteins, COS 7 cells were transfected with either wildtype, mutant TMEM43, or both plasmids at wildtype:mutant ratios of 1:1 and 1:2 for 5 days. Five days following transfection, cells were washed in PBS and lysed in Triton X lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, and 1% Triton X-100) [4], followed by centrifugation at 20,000 ×g for 15 min. The supernatant, comprised of the soluble fraction, and the pellet (insoluble fraction) was resuspended in RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific). Protease inhibitor tablets (Roche) were added to each of the protein fractions and 40 μg of soluble and insoluble protein fractions were loaded onto a 10% protein gel (Pierce). Immunoblotting was performed as described elsewhere [11]. The following primary antibodies and titers were used following the manufacturer's instructions: desmocollin-2/3 (Zymed Laboratories, #32-600, 1:125), desmoglein-2 (Abcam, #ab14415, 1:1000), desmoplakin (United States Biological, #D3221-89, 1:100), and junctional plakoglobin (Zymed Laboratories, #13-8500, 1:125).

Solubility of TMEM43 and other nuclear envelope proteins

Unlike desmosomal and other nuclear envelope proteins, TMEM43 readily solubilizes in Triton X-100. This effect is obviated if the solubility assay is performed on nuclear envelope extract rather than whole cell lysate [8]. Hence, nuclear envelope membranes were extracted from transfected COS- 7 cells, followed by solubility assays. To extract the nuclear envelope, the cytoplasmic fraction and nuclei of transfected cells were separated using ProteoJET cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extraction kit (Fermentas). Nuclei were washed with 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) and nuclear envelope membranes were prepared by treatment with heparin and DNase I [13]. Briefly, heparin and DNase I were added to the nuclei suspended in 20 mM HEPES at a final concentration of 0.6 mg/108 nuclei and 0.5 mg/108 nuclei, respectively. The nuclei were stirred for 1 hour at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 20 minutes (4°C). The pellet was resuspended in buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.32 M sucrose, 42.8 mM β-mercaptoethanol), and centrifuged again as described above. The pelleted nuclear envelope membranes were lysed with Triton X lysis buffer, followed by separation of the soluble and insoluble fraction, as described earlier. Protease inhibitor tablets (Roche) were added to both fractions. Approximately, 10 μg of soluble and insoluble nuclear envelope protein was loaded on a protein gel and immunoblotting was performed. Differential solubility patterns were assessed for TMEM43 (GFP antibody, Invitrogen, #A11122, 1:1000), lamin B (Santa Cruz, #sc-6217, 1:1000) and emerin (Santa Cruz, #sc-81552, 1:1000) by immunoblotting at the indicated titers.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

COS-7 cells were grown and transfected in 8-well chamber plates as described above. Cells were fixed using 2% formaldehyde in phosphate buffer saline (PBS), permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X-100 in PBS, and washed several times with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Primary antibodies against lamin B (Santa Cruz, #sc-6217, 1:50) and emerin (Santa Cruz, #sc-81552, 1:50) were diluted in 0.5% BSA in PBS. Fixed cells were incubated at 4°C overnight with the antibody at the indicated titer, followed by incubation at room temperature for one hour with appropriate cyanine-3 labeled secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst stain (Invitrogen). Cells were visualized using Nikon Eclipse TS 100 fluorescent microscope.

Real-time quantitative PCR (QPCR)

Mewborn and colleagues have previously shown that chromosome 13 exhibits a high percentage of misexpressed genes in lamin A mutant hearts. Among these genes, abnormal expression of KCTD12, LMO7, MBNL2, and RAP2A were shown to be associated with striated muscle dysfunction [14]. Lamin A/C also associates with TMEM43 [8]. Therefore, we quantified the expression of these genes as described [11] in COS-7 cells transfected with either the wildtype or mutant plasmid.

RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol (Invitrogen) and RNA quantity was determined on an Agilent Nanodrop. One μg of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand System (Invitrogen). QPCR was performed using Express SYBR GreenER kit with premixed ROX (Invitrogen) on gene specific primers previously published by Mewborn and colleagues [14]. Experiments were performed using two biological replicates and three technical replicates. Samples were run on an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System. Threshold cycle values were normalized to gylceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. ΔΔCt values were estimated for each gene and unpaired Student's t-tests were performed to compare data obtained from wildtype and mutant plasmid transfected cells. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Clinical evaluation and mutation screening

Novel variants were identified in three desmosomal genes, DSG2, DSC2 and PKP2, that were absent in 150 control individuals. We also report two known mutations in PKP2 (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Significance of novel desmosomal mutations assessed by localization within functionally important domains and their evolutionary conservation. (A) DSG2, p.Ile70Val (c.208A > G); (B) DSC2, p.Thr412Asnfs*2 (c.1234_1235insA); (C) PKP2, p.L847Rfs*83 (c.2540delT). The numbered white box signifies an exon; the arrow signifies the site of mutation; the grey background indicates identity across species; the box surrounding an amino acid indicates the mutated residue. S, signal domain; P, preprotein domain; EC, extracellular domain; EA, extracellular anchor; TM, transmembrane domain; IA, intracellular anchor domain; ICS, intracellular cadherin-typical segment domain; LD, linker domain; RUD, repeat unit domain; TD, terminal domain.

Family I. The proband (I.1) was a compound heterozygote with a novel DSG2 exon 3 mutation, c. 208A > G (p.Ile70Val), and a previously reported PKP2 truncation mutation, c.397 C > T (p.Gln133*). The Gln133* mutation has been observed in patients that do not fully satisfy ARVC diagnostic criteria [15]. The proband fulfilled 2 major diagnostic criteria (Table 1) [10]. Although the DSG2 Ile70Val mutation was not predicted to be pathological, the Ile residue at this position was highly conserved among species (Figure 1A). Each of two available clinically unaffected family members possessed either the DSG2 Ile70Val or the PKP2 Gln133* mutation.

Family II. The proband (II.1) had an insertion at c.1234_1235insA in exon 9 of DSC2 resulting in a frameshift followed by premature truncation of the protein (p.Thr412Asnfs*2). This region is conserved among species and the predicted protein would lack part of the extracellular, transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic components (Figure 1B). One affected sibling (II.2) shared the same mutation as the proband (Table 1). The clinical manifestation of the disease at a young age in both the proband and the sibling is consistent with the pathogenicity of the DSC2 Thr412Asnfs*2 mutation.

Family III. The proband (III.1) had a deletion at c.2540delT in exon 13 of PKP2, resulting in a loss of a stop codon and a mutant protein that was 48 amino acids longer than the wildtype protein (p.Leu847Argfs*83). This region is conserved among species (Figure 1C). One other family member shared the same deletion as the proband (III.2). The proband only partially satisfied ARVC diagnostic criteria, probably because the mutant protein functions similarly to the wildtype PKP2 protein. There was insufficient clinical information to make a diagnosis in family member III.2.

Family IV. The proband (IV.1) fulfilled the ARVC diagnostic criteria and presented with a previously reported deletion and insertion in exon 11 of PKP2 at c.2197-2202delinsG that resulted in a premature truncation of the protein (p.His733Alafs*8) (Table 1) [16].

No mutations in TMEM43 were identified in the 11 probands, suggesting that mutations in this gene are a relatively rare cause of ARVC.

Functional characterization of mutant TMEM43

Desmosomal and nuclear envelope protein stability

Previous studies have suggested that disruption of cell-cell adhesion because of desmosomal dysfunction is a major mechanism of ARVC. Structural instability of desmosomes leads to localization of constituent proteins in the cytoplasmic instead of the cell membrane fraction following centrifugation in the presence of nondenaturing detergents [5, 12]. We assessed the effect of mutant Ser358Leu TMEM43 on solubility patterns of four desmosomal proteins (desmocollin-2, desmoglein-2, desmoplakin, and junctional plakoglobin) and the cellular distribution of three nuclear envelope proteins (TMEM43, lamin B and emerin).

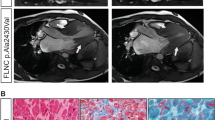

Solubility assays indicated similar localization of desmocollin-2, desmoglein-2, desmoplakin, and junctional plakoglobin in the cell membrane bound insoluble fraction, irrespective of the transfection dosage for both wildtype and mutant TMEM43 (Figure 2A, data not shown for 1:1 dosage). Mutant TMEM43 and lamin B were present in the insoluble nuclear membrane bound fraction (Figure 2B). Although emerin was present in both soluble and insoluble fractions, there was no evident change in the ratio between the two fractions. Immunofluorescence microscopy also showed that TMEM43, lamin B, and emerin were localized to the nuclear membrane in both wildtype and mutant TMEM43 transfected cells (Figure 3). Thus, these data suggest that mutant TMEM43 does not change its own localization or that of its binding partners lamin B and emerin.

Solubility assays. Solubility patterns for (A) desmosomal and (B) nuclear envelope proteins were assessed by immunoblots for soluble and insoluble protein fractions extracted from COS-7 cells transfected with wildtype (WT) TMEM43, mutant (Mut) TMEM43, or a 1:2 ratio of wildtype to mutant (WT + Mut) TMEM43. Sol, soluble fraction containing cytoplasmic (Cyt) proteins; Insol, insoluble fraction containing membrane bound proteins. No differences in solubility patterns were found, suggesting that the presence of mutant TMEM43 did not alter the stability of TMEM43 or of other desmosomal or nuclear envelope proteins.

Gene expression changes

We examined the effect of mutant TMEM43 on mRNA expression of four genes, LMO7, KCTD12, MBNL2 and RAP2A, located on chromosome 13, that have been shown to have abnormal expression in the setting of laminopathies with striated muscle dysfunction [14]. QPCR preformed on these four genes showed no significant change in their mRNA expression in cells transfected with wildtype and mutant TMEM43, respectively (Table 2). Thus, while TMEM43 interacts with lamin A, we conclude that mutant TMEM43 protein, unlike mutant lamin A, does not alter expression of at least four representative genes on chromosome 13.

Discussion

The mechanisms by which mutant desmosomal proteins cause ARVC have been partially elucidated. Previous studies have shown that overexpression in cell lines of mutant desmoplakin and desmocollin-2 associated with ARVC results in cytoplasmic distribution of these proteins instead of normal membrane localization [5, 12] and knockdown of DSP leads to nuclear localization of plakoglobin [17]. In Pkp -/- null mice, plakophilin-2 and plakoglobin were found to be essential for adherence of desmoplakin to partner desmosomal proteins [4]. More recently, the Ser358Leu mutation in TMEM43 has been suggested [7] as a putative cause for ARVC in a large kindred that we mapped to chromosome 3p23 [6]. Furthermore, decreased expression of plakoglobin has been shown in tissues of patients with ARVC including those with TMEM43 mutations [9, 18]. To uncover potential mechanisms by which TMEM43 mutations may lead to ARVC, we first sought to determine its frequency in the ARVC population by screening for mutations in this gene along with five other desmosomal genes; and we then examined the specific effects of Ser358Leu mutant TMEM43 on stability of desmosomal and nuclear envelope proteins and on gene expression in the COS-7 heterologous cells system.

Our patient cohort lacked TMEM43 mutations, suggesting that mutations in this gene are a relatively rare cause of ARVC and consistent with a previously reported screen [8]. However, we have identified three novel mutations in three probands. The presence of two mutations, i.e., p.Ile70Val in DSG2 and p.Gln133* in PKP2 in the Family I proband, contrasted with unaffected family members who had only one mutation each, suggests that co-segregation of these two mutations in the proband may have led to the development of ARVC. Earlier studies have also suggested that digenic and compound heterozygous mutations are frequent in desmosomal genes and may be responsible for severe ARVC [19–21]. The DSC2 (p.Thr412Asnfs*2) frameshift mutation is likely pathogenic since it results in a truncated protein and both individuals in Family II with this mutation fulfilled ARVC diagnostic criteria.

As discussed earlier, ARVC is primarily a disease of the desmosomes. Based on this observation, we hypothesized that mutant TMEM43 protein would disrupt structure and function of desmocollin-2, desmoglein-2, desmoplakin, and junctional plakoglobin, leading to ARVC. However, we found no evidence of disruption or mislocalization of mutant TMEM43 or of desmosomal proteins in transfected COS-7 cells. Thus, our data suggest that mutant TMEM43 does not directly affect desmosomal protein localization on even increasing the dosage of mutant protein.

TMEM43 is an INM protein that has a large hydrophilic domain located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen. It helps to maintain the nuclear envelope structure by organizing protein complexes in the INM and it is known to associate with other nuclear envelope proteins such as lamins and emerin [8]. Lamins have been extensively studied primarily because mutations in lamin A/C lead to dilated cardiomyopathy [22] and lamin B maintains nuclear shape and mechanical integrity [23]. Since mutations in emerin cause Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and TMEM43 can affect emerin distribution, it has been suggested that TMEM43 mutations could result in muscular dystrophy [8]. We therefore sought to determine whether mutant TMEM43 affects the localization of emerin and lamin B, which in turn might lead to ARVC. However, our solubility and immunofluorescence experiments indicated no such abnormalities.

As mentioned above, mutations in lamin A can lead to dilated cardiomyopathy. Lamin A/C, encoded by LMNA, is also a member of the LINC complex (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) that links the nucleus to the cytoplasm and also associates with TMEM43. Mewborn and colleagues showed that lamin A mutants exhibited misexpression of genes located on chromosome 13, which may potentially lead to laminopathies [14]. We therefore examined the effect of mutant TMEM43 protein on mRNA expression of four genes, namely, LMO7, KCTD12, MBNL2 and RAP2A, all of which are located on chromosome 13, are associated with striated muscle dysfunction, and exhibit abnormal expression in the presence of a LMNA mutation [14]. However, in the presence of mutant TMEM43, these genes exhibited normal mRNA expression.

Conclusions

We identified three new mutations in desmosomal genes in 11 probands screen; however, no TMEM43 mutations were identified. The absence of a mutation in majority of our ARVC patients, as in prior studies, suggests the presence of other genetic contributors to this disease. This study also confirms normal cellular localization and stability of the analyzed desmosomal and nuclear proteins in COS 7 cells transfected with mutant TMEM43. Furthermore, mutant TMEM43 did not alter the expression of genes that are suggested to be associated with laminopathies. A limitation of this study is that a heterologous cell system was used, which may not completely reflect the effect of TMEM43 mutations in cardiomyocytes. Additional studies in cardiomyocytes may be required to uncover a clearer pathogenetic link between the Ser358Leu mutation in TMEM43 and the development of ARVC.

References

Ahmad F: The molecular genetics of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia-cardiomyopathy. Clin Invest Med. 2003, 26 (4): 167-178.

Thiene G, Basso C, Danieli G, Rampazzo A, Corrado D, Nava A: Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy A Still Underrecognized Clinic Entity. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1997, 7 (3): 84-90. 10.1016/S1050-1738(97)00011-X.

Awad MM, Calkins H, Judge DP: Mechanisms of disease: molecular genetics of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008, 5 (5): 258-267. 10.1038/ncpcardio1182.

Grossmann KS, Grund C, Huelsken J, Behrend M, Erdmann B, Franke WW, Birchmeier W: Requirement of plakophilin 2 for heart morphogenesis and cardiac junction formation. J Cell Biol. 2004, 167 (1): 149-160. 10.1083/jcb.200402096.

Yang Z, Bowles NE, Scherer SE, Taylor MD, Kearney DL, Ge S, Nadvoretskiy VV, DeFreitas G, Carabello B, Brandon LI, et al: Desmosomal dysfunction due to mutations in desmoplakin causes arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2006, 99 (6): 646-655. 10.1161/01.RES.0000241482.19382.c6.

Ahmad F, Li D, Karibe A, Gonzalez O, Tapscott T, Hill R, Weilbaecher D, Blackie P, Furey M, Gardner M, et al: Localization of a gene responsible for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia to chromosome 3p23. Circulation. 1998, 98 (25): 2791-2795.

Merner ND, Hodgkinson KA, Haywood AF, Connors S, French VM, Drenckhahn JD, Kupprion C, Ramadanova K, Thierfelder L, McKenna W, et al: Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5 is a fully penetrant, lethal arrhythmic disorder caused by a missense mutation in the TMEM43 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2008, 82 (4): 809-821. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.010.

Bengtsson L, Otto H: LUMA interacts with emerin and influences its distribution at the inner nuclear membrane. J Cell Sci. 2008, 121 (Pt 4): 536-548.

Christensen AH, Andersen CB, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Haunso S, Svendsen JH: Mutation analysis and evaluation of the cardiac localization of TMEM43 in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Clin Genet. 2011, 80: 256-264. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01623.x.

Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, Calkins H, Corrado D, Cox MG, Daubert JP, et al: Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation. 2010, 121 (13): 1533-1541. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840827.

Rajkumar R, Konishi K, Richards TJ, Ishizawar DC, Wiechert AC, Kaminski N, Ahmad F: Genomewide RNA expression profiling in lung identifies distinct signatures in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and secondary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010, 298 (4): H1235-H1248. 10.1152/ajpheart.00254.2009.

Beffagna G, De Bortoli M, Nava A, Salamon M, Lorenzon A, Zaccolo M, Mancuso L, Sigalotti L, Bauce B, Occhi G, et al: Missense mutations in desmocollin-2 N-terminus, associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, affect intracellular localization of desmocollin-2 in vitro. BMC Med Genet. 2007, 8: 65-

Buchner K, Otto H, Hilbert R, Lindschau C, Haller H, Hucho F: Properties of protein kinase C associated with nuclear membranes. Biochem J. 1992, 286 (Pt 2): 369-375.

Mewborn SK, Puckelwartz MJ, Abuisneineh F, Fahrenbach JP, Zhang Y, MacLeod H, Dellefave L, Pytel P, Selig S, Labno CM, et al: Altered chromosomal positioning, compaction, and gene expression with a lamin A/C gene mutation. PLoS One. 2010, 5 (12): e14342-10.1371/journal.pone.0014342.

van Tintelen JP, Entius MM, Bhuiyan ZA, Jongbloed R, Wiesfeld AC, Wilde AA, van der Smagt J, Boven LG, Mannens MM, van Langen IM, et al: Plakophilin-2 mutations are the major determinant of familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006, 113 (13): 1650-1658. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.609719.

Dalal D, Molin LH, Piccini J, Tichnell C, James C, Bomma C, Prakasa K, Towbin JA, Marcus FI, Spevak PJ, et al: Clinical features of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy associated with mutations in plakophilin-2. Circulation. 2006, 113 (13): 1641-1649. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.568642.

Garcia-Gras E, Lombardi R, Giocondo MJ, Willerson JT, Schneider MD, Khoury DS, Marian AJ: Suppression of canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling by nuclear plakoglobin recapitulates phenotype of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2006, 116 (7): 2012-2021. 10.1172/JCI27751.

Asimaki A, Tandri H, Huang H, Halushka MK, Gautam S, Basso C, Thiene G, Tsatsopoulou A, Protonotarios N, McKenna WJ, et al: A new diagnostic test for arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360 (11): 1075-1084. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808138.

Bhuiyan ZA, Jongbloed JD, van der Smagt J, Lombardi PM, Wiesfeld AC, Nelen M, Schouten M, Jongbloed R, Cox MG, van Wolferen M, et al: Desmoglein-2 and desmocollin-2 mutations in dutch arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomypathy patients: results from a multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009, 2 (5): 418-427. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.839829.

Xu T, Yang Z, Vatta M, Rampazzo A, Beffagna G, Pilichou K, Scherer SE, Saffitz J, Kravitz J, Zareba W, et al: Compound and digenic heterozygosity contributes to arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 55 (6): 587-597. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.020.

Bauce B, Nava A, Beffagna G, Basso C, Lorenzon A, Smaniotto G, De Bortoli M, Rigato I, Mazzotti E, Steriotis A, et al: Multiple mutations in desmosomal proteins encoding genes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Heart Rhythm. 2010, 7 (1): 22-29. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.070.

Ahmad F, Seidman JG, Seidman CE: The genetic basis for cardiac remodeling. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005, 6: 185-216. 10.1146/annurev.genom.6.080604.162132.

Vergnes L, Peterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K: Lamin B1 is required for mouse development and nuclear integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101 (28): 10428-10433. 10.1073/pnas.0401424101.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/13/21/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Catherine B. Jackson, PhD, the University of Pittsburgh Center for Biological Imaging, for guidance with fluorescent imaging; and Louise Martin, RN, BSN, and. Mohun Ramratnum, MD, UPMC Heart and Vascular Institute, for assistance in recruitment of subjects and collection of clinical information, respectively.

Funding

This study was supported by a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development Grant, a grant from The Pittsburgh Foundation, and NIH grants U01 HL108642 and R03 HL095401 to FA, and an American Heart Association Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship to JS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RR participated in the conception and design of the study, performed all molecular biology experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. JS maintained cell culture, performed nuclear protein isolation and immunoblotting. BM carried out acquisition of clinical data. CES recruited and evaluated subjects at Harvard Medical School. FA conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, recruited and evaluated subjects from the University of Pittsburgh, assisted with data interpretation, and wrote the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajkumar, R., Sembrat, J.C., McDonough, B. et al. Functional effects of the TMEM43 Ser358Leu mutation in the pathogenesis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. BMC Med Genet 13, 21 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-13-21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-13-21