Abstract

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex disorder thought to result from an interaction between environmental and genetic predisposing factors which have not yet been characterised, although it is known to be associated with the HLA region on 6p21.32. Recently, a picture of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI), consequent to stenosing venous malformation of the main extra-cranial outflow routes (VM), has been described in patients affected with MS, introducing an additional phenotype with possible pathogenic significance.

Methods

In order to explore the presence of copy number variations (CNVs) within the HLA locus, a custom CGH array was designed to cover 7 Mb of the HLA locus region (6,899,999 bp; chr6:29,900,001-36,800,000). Genomic DNA of the 15 patients with CCSVI/VM and MS was hybridised in duplicate.

Results

In total, 322 CNVs, of which 225 were extragenic and 97 intragenic, were identified in 15 patients. 234 known polymorphic CNVs were detected, the majority of these being situated in non-coding or extragenic regions. The overall number of CNVs (both extra- and intragenic) showed a robust and significant correlation with the number of stenosing VMs (Spearman: r = 0.6590, p = 0.0104; linear regression analysis r = 0.6577, p = 0.0106).

The region we analysed contains 211 known genes. By using pathway analysis focused on angiogenesis and venous development, MS, and immunity, we tentatively highlight several genes as possible susceptibility factor candidates involved in this peculiar phenotype.

Conclusions

The CNVs contained in the HLA locus region in patients with the novel phenotype of CCSVI/VM and MS were mapped in detail, demonstrating a significant correlation between the number of known CNVs found in the HLA region and the number of CCSVI-VMs identified in patients. Pathway analysis revealed common routes of interaction of several of the genes involved in angiogenesis and immunity contained within this region. Despite the small sample size in this pilot study, it does suggest that the number of multiple polymorphic CNVs in the HLA locus deserves further study, owing to their possible involvement in susceptibility to this novel MS/VM plus phenotype, and perhaps even other types of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although multiple sclerosis is the most prevalent neurological disease in the young adult population, it is catalogued as a neurodegenerative disorder of unknown aetiology [1]. Indeed, despite the proposal of inflammatory, infective, and autoimmune factors as pathogenic agents in this disease, their links with its aetiology still remain to be elucidated [2, 3]. Nonetheless, genetic studies on twins and siblings suggest that susceptibility genes may play a role in predisposition. Indeed, candidate gene and whole genome association studies, as well as CNV detection on SNP-based arrays involving more than hundred thousand markers, have identified several possible susceptibility loci in the human genome. The HLA locus on 6p21.32 is the most confidently associated of these [4–9], among a few others of uncertain statistical significance [10, 11]. However, even when controls are accurately randomised, undetectable errors may occur, especially linked to the geographical origins of the population and known differences in SNPs density, depending on the various human chromosomes or even genomic regions involved. These errors may inflate the apparently significant differences between patients and controls (genomic inflation) generating false positives or negatives and impeding true recognition of the associated loci [11].

As recently reported [11], and as recommend by the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium [12, 13], in order to circumvent this issue, allowing unbiased data to be collected and replication of the associations in the identified loci to be performed, an enormous number of individuals have to be analysed and functional studies are required.

All the studies into the genetics of MS performed so far have been carried out on SNP-based arrays. However, although SNPs do contribute to inter-individual variation across the genome, it is now well recognised that copy number variations (CNVs), typically ranging from 1 kb to several Mb, also influence genetic variations and disease susceptibility [14, 8]. It is evident that CNVs account for more nucleotide variations between individuals, and, furthermore, the functional significance of these variations might be more immediate, especially if they are located within genes, regulatory regions or known imprinted regions, since the possible consequence of genome imbalance(s) may be more easily interpretable.

In fact, the development of robust high throughput platforms based on comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH) capable of identifying thousands of genomic variations has greatly improved research in this direction, as recently demonstrated in the case of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, a major neurodegenerative disorder in which non-polymorphic sub-microscopic duplications and deletions seem to be frequent in sporadic cases [15].

Recently, we described the peculiar association of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) in patients with MS [16]. CCSVI is due to stenosing venous malformations (VM) which affect the azygous and the jugular veins, leading to significant anomalies in cerebral venous outflow haemodynamics [16–20]. Insufficient cerebral venous drainage represents a mechanism potentially related to increased iron stores, suggesting a pathogenic role in the progression or even pathogenesis of this disease [21–23].

Taking into account these premises, the aim of our pilot study was to use an innovative CGH array to investigate the occurrence of CNVs underlying genome imbalances in the major locus (HLA, chromosome 6p21) associated with MS. In order to sub-select a specific phenotype, we decided to recruit patients with the "plus" phenotype (VM-CCSVI and MS). The objective was thus to use this patient category to explore the genomic configuration of the locus in question, thereby seeking to identify specific regions for further investigation in a wider population.

Methods

Subjects

Fifteen patients affected by relapsing-remitting MS, diagnosed according to the revised McDonald criteria [24], were recruited for the study, and their Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [25] and Multiple Sclerosis Severity Scores (MS-SS) [26, 27] were determined. In our population, MS was associated with CCSVI venous malformation, documented by a sequential Colour-Doppler/selective venography protocol [16]. In fact, Colour Doppler allowed us to determine the number of anomalous parameters linked to CCSVI, as well as the Venous Haemodynamic Insufficiency Severity Score (VHISS) based on the number of venous segments exhibiting reflux or blocked flow [18, 28]. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the selected patients are given in the Additional file 1 Table S1. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in the study.

DNA from the 15 patients was extracted by a protocol recommended by Agilent. Highly concentrated DNA was checked for quality using a NanoDrop (260/280 ratio = 1.8 and 260/230 ratio = 2.0), and DNA integrity was evaluated on agarose gel at 1% in TBE 1×.

Ethical aspects

All the experimental research that is reported in the manuscript was performed with the approval of the University of Ferrara Ethical Committee (Document n. 7, approved by the 27th of May 2004). The research carried out on humans was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical data are given as median and interquartile range. For genotype-phenotype correlations, patients with an overall number of CNVs within the 90th percentile were considered. Genotype-phenotype correlations were further analysed by means of both the Spearman rank correlation test and linear regression analysis, including evaluation of the slope and X and Y intercept, followed by a Run Test. P values of < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

HLA locus typing

HLA-DRB1 low resolution SSP typing was performed using commercial kits (Biotest DRB SSP Kit, Lot B812151) in all 15 patients studied.

Microarray design, hybridization and data analysis

MS-CGH microarray design was carried out using the web-based Agilent eArray database, version 5.4 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) [29], as previously performed [30]. The high density aCGH search function in eArray was used to turn the genomic region chr6:29,900,001-36,800,000 (March 2006, human reference sequence, NCBI Build 36.1, hg18) into a probe set by selecting the maximum number of exonic, intronic and intragenic 60 mer oligonucleotide CGH probes available in the database. This set included 43102 probes that were used to reach the array format of 4 × 44 K, creating four identical 44 K arrays on a single slide for simultaneous analysis of four different samples.

This platform, termed MS-CGH, is a high-density microarray with a resolution of one probe per 160 bp which permits rapid determination of the molecular profile, identifying the presence of heterozygous or homozygous copy number variations (CNVs) in the genomic region studied.

The platform informations have been submitted to the online data repository Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [31], with accession number GPL10049.

Labelling and hybridisation were performed following the protocols provided by Agilent (Agilent Oligonucleotide Array-Based CGH for Genomic DNA Analysis protocol v5.0), as described elsewhere [30]. The array was analysed with the Agilent scanner and Feature Extraction software (v9.1). A graphical overview was obtained and data analysis performed using DNA Analytics software (v4.0.36). The standard set-up of the ADM-2 statistical analysis in this software package was employed for identification of duplications and deletions. In this set-up, and in the case of autosomal genes, heterozygous deletions are visualised with values of minus 1, and homozygous deletions as minus infinite (-4 in CGH analytics). The corresponding values for heterozygous and homozygous duplications are plus 0.5 and plus 1, respectively. At least 4 consecutive non-overlapping probes reaching these values were required for a positive reading, together with an absence of known SNPs in the region covered by the relevant probes. All 15 patients were assessed in duplicate in order to confirm the validity of the results.

Bioinformatics analysis of gene networks

Pathway analysis and literature mining was performed using Pathway Studio software from Ariadne Genomics Inc. The Pathway Studio database contains millions of regulatory and interaction events from all PubMed abstracts, and more than 350,000 full-text articles extracted by MedScan natural language processing technology. We employed the "Build Pathway" navigation tool in Pathway Studio to locate literary evidence supporting the functional association of measured genes with angiogenesis and other processes linked to blood vessel formation, as well as to immunity and neurodegeneration.

Results

CGH-ARRAY data

Comparison with the CNV database revealed 234 known polymorphic CNVs in the 15 patients [32], thereby confirmed that the HLA locus is highly polymorphic in terms of genomic imbalance, as expected considering its known high density of SNPs. The distribution of the CNVs among patients, both in terms of number and density, is shown in Figure 1.

Additional file 2 Table S2 reports all the CNVs identified in patients. An example CGH profile, corresponding to patient PF, is shown in Additional file 3 Figure S1.

The complete CGH datasets have been submitted to the online data repository Gene Expression Omnibus [31], under accession number GSE20334.

Genotype-phenotype correlation: statistical analysis

CNV profiling

The number of CNVs within the 90th percentile was correlated with the clinical parameters of the patients (Figure 2, top panel, Additional file 1 Table S1). Fourteen patients out of the those coded as MC (52 CNVs vs. median (IR) 23 (13) of our patient population) fell within the 90th percentile, and were therefore further analysed by both the Spearman rank correlation test and linear regression analysis (Additional file 1 Table S1). Both analyses demonstrated a significant and firm correlation between the number of CNVs and the number of stenosing venous malformations identified (Spearman: r = 0.6590, p = 0.0104; linear regression analysis r = 0.6577, p = 0.0106) (Figure 2 bottom panel and Figure 3).

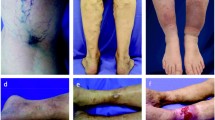

Stenosing venous malformation associated to MS and genotype-phenotype correlation. Top Panel: Exemplification of stenosing venous malformation associated to MS. Significant stenosis (arrow) of the left internal jugular vein (L IJV). B) Membranous obstruction of the outlet of the azygous vein (o AZY) into the superior vena cava (SVC). Bottom Panel) Linear regression analysis. A significant correlation between the number of CNVs and the number of venous malformations detected by means of selective venography was found (r = 0.6577, p = 0.0106).

Number of total (A), intragenic (B) and extragenic (C) known CNVs reported in the Database of Genomic Variants () per patient http://projects.tcag.ca/variation.

No correlation was found between extragenic or intragenic CNVs and the number of stenosing VMs, respectively. No additional correlations were found between CNVs and the number of anomalous Doppler haemodynamic parameters, or with the VHISS. No correlation was found between patient phenotypes, either for MS and VM, and the presence of specific CNVs, CNV haplotypes or CNV distribution.

HLA typing

Statistical analysis did not yield significant results. The HLA-DRB1*15 class region, known to be a locus with a major contribution to the risk of MS [33], did not strongly occur in our population, and seemed to be unrelated to VM clinical signs or CNV number (see Additional file 1 Table S1).

Since the patients' parents were not available for study, haplotypes and consequently allele phases could not be established.

Pathways and gene network functional bioinformatics analysis

211 genes were contained within the region covered by our CGH array.

Since the phenotype in question is characterised by multiple sclerosis and venous malformation, we applied a bioinformatics tool to select genes known to be involved in angiogenesis and venous development, as well as those linked to multiple sclerosis, immunity and neurodegeneration. Interestingly, several genes have been linked to these processes. HSPA1L and HSPA1A have been correlated with MS, diabetes and other immunity disorders, as well as regulatory functions such as chromatin remodelling, neuroprotection, protein folding, and regenerative-degenerative tools like neurodegeneration, neuron toxicity, cell survival, synaptic transmission and even aging factors (senescence and telomere maintenance). The gene GRM4 also seems to interact with many proteins linked to MS (Figure 4A)

By focusing on specific functional pathways, for example angiogenesis, and considering the plus phenotype of our patients (venous malformation), we obtained a more selective puzzle of interactions (Figure 4B). GRB2 and HSPA1A and B genes directly act on angiogenesis, TAF11 is known to be involved in artery passage, and the E2F1 transcription factor is known to be an angiogenesis positive inducer in hepatitis and cancer. Interestingly, HLA-DQA2 may also be implicated in angiogenesis through its interaction with CD4.

Discussion

We recently described the CCSVI/VM phenotype associated with MS, which might participate in iron accumulation in the brain, a feature known to be present in several neurodegenerative diseases, including MS [34–36].

We designed a locus-specific CGH array in order to explore the occurrence of CNVs in the HLA region in 15 patients with the peculiar association of CCSVI/VM and MS phenotype.

CNVs are very abundant in the human genome, being involved in genetic variation among populations in a similar fashion to SNPs. Innovatively, this strategy was adopted instead of SNP-based arrays, as the latter tend to suffer from false positive and false negative results, in addition to the fact that no algorithm able to unequivocally detect genomic variants of less than about 30 Kb seems to be currently available.

However, CGH CNV detection also has inherent limitations, such as probe density, and failure of hybridisation due to the presence of SNPs in the probed region. In addition, it is widely recommended that each novel CNV detected by CGH be validated by an alternative method (for example RealTime PCR or qPCR). Nevertheless, being aware of the limit of confidence of CNV identification by CGH, the advantage of searching for CNVs by this technique was the possibility of directly correlating known, validated CNVs with a potential function, which can be related to imbalance either of specific gene(s) or of genomic regulatory regions. In fact, the CGH approach allows fine mapping of the identified CNVs in non-genic regions, which may be correlated to gene regulatory functions, epigenetic changes or other non-coding functions. Indeed, the potential impact on the expression regulation of many genes by genomic "perturbation" of one (or more) specific genomic region(s) is intriguing, as it tentatively implicates it in a variety of different complex phenotypes. This is the reason why this genetic model applies very well to polygenic or multi-factorial diseases [37].

As expected, we detected a high number (234) of known CNVs, thereby confirming that the HLA region is very rich in structural variations, in addition to its known high polymorphism in terms of SNPs.

Analysing the distribution of the polymorphic CNVs identified in patients, we observed a peak of CNV numbers within the HLA region. Outside this specific region however, the number of CNVs per patients remained high, though with variable distribution.

We also genotyped the HLA-DRB1 region in our patients. Statistical analysis failed to show any correlation between the presence of the HLA-DRB1*15 allele and VM-related clinical signs. It is well known that SNPs or complex polymorphism density is haplotype-dependent within the human Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) [38].

However, in order to link the CNV profile and the HLA haplotype, phasing both polymorphism types is mandatory. In addition, no studies have yet fully characterised either CNVs (array-based) or SNPs in the whole genomic region of the HLA locus. For this reason, although the frequency of HLA-DRB1*15 in our patients' cohort seems to be lower than the one reported in classic MS, it is not possible to conclude whether the VM phenotype has a distinct association with the HLA haplotype, especially when one considers our small patient number. This seems to be a major goal for future studies.

Interestingly, while no statistically significant association was found between CNV type or distribution and patient phenotype, the overall number of CNVs showed a significant correlation with the number of stenosing malformations demonstrated by venography in the extracranial segments of the cerebrospinal veins. However, the major shortcoming of this pilot study is the dimension of the sample, which should be expanded in the future to strengthen the as yet unconfirmed significance of our findings. The small number of patients also affected further sub-analysis, and both the extragenic and the intragenic component of the CNVs were not found to be associated to the phenotype VM. Moreover, no correlations were discovered between CNVs and either the number of anomalous Doppler haemodynamic parameters or the VHISS.

Nonetheless, the phenotype studied here, correlated with the CNVs, is strongly associated to MS (OR 43, p < 0.0001) [16]; we speculate that the presence of VM may contribute to the increase in iron accumulation in MS as a pathogenic component of the disease [36]. The hampered cerebral venous return consequent to extracranial venous malformations is peculiar to MS, and was not found in a miscellany of patients affected by other neurodegenerative disorders characterized by iron stores, such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [16, 18, 36]. Theoretically, venous haemodynamic overload may facilitate local microbleeding following damage to vein or venule walls, becoming a distinctive mechanism of iron deposition in MS, as we recently demonstrated [36].

Taken as a whole, our data, though preliminary, suggest that the number of polymorphic CNVs in the HLA region did correlate with the number of VMs in our patient cohort. Since HLA is the only region consistently associated with the disease, further studies are certainly needed to discriminate whether the CNV findings are specific for MS patients with venous malformations or, instead, are similarly observed in the general MS population, regardless of the presence of vascular malformations.

In addition, the region studied contains 211 known genes. Using a functional bioinformatics tool, we identified many genes interacting in both neurodegenerative and angiogenesis circuits. Notably, HSPA1L, HSP1A and HSP1B and the HLA-DQ2 gene network in both pathways. Heat-shock proteins (HSPs) represent a group of regulatory proteins involved in a variety of processes, including immunity and angiogenesis [39, 40]. In particular HSPA1L expression is modulated by ETS1 transcription factor and by SP100, a nuclear autoimmune antigen. Interestingly, genes negatively regulated by ETS1 and up-regulated by SP100, such as HSPA1L, have anti-migratory or anti-angiogenic properties [41].

MS possesses a recognised major heritable component, since its susceptibility is associated with the MHC class II region, especially the HLA-DRB5*0101-HLA-DRB1*1501-HLA-DQA1*0102-HLA-DQB1*0602 haplotypes, which dominate genetic contribution to MS susceptibility [42]. Interestingly, HLA-DQA2 is known to be involved in pro-inflammatory CD4(+) T-cell-mediated autoimmune diseases such as MS and type 1 diabetes [43]. CD4 is also a very well known inhibitor of tumour angiogenesis [44], thus supporting a link between the two pathways. The interpretation of the pathway interaction is obviously complex, but it does suggest biological and functional links among these genes as well as, intriguingly, between angiogenesis and immunity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we present an exploration of CNVs, identified by CGH-based methodology, in a small group of patients with associated MS and VM. We identified 234 known CNVs, and determined that the distribution of CNVs along the HLA region showed no peculiar topography in the patients studied.

We found that the overall number of CNVs correlates significantly with the venous malformative phenotype. Consistently with the general significance of CNVs, putatively involved in regulation of gene expression, this finding is interesting, since it may lend weight to the possibility that the number of structural variations within regulatory regions represents a genomic "perturbation" which increases susceptibility for the VM phenotype associated with MS we describe. Obviously, confirmation of these findings will require further studies aimed at comparing CNV profiles in patients with the MS/VM phenotype to those in patients presenting MS alone. This will distinguish peculiar association(s), and potentially disclose common/different underlying genotypes. Regarding specific candidate genes whose expression could potentially be disturbed by genomic imbalance or "perturbation", pathways analysis suggested that genes involved in angiogenesis and immunity could be proteins worthy of further investigation.

Moreover, we hope that our custom array will be useful for other studies, perhaps to identify structural changes in the numerous disorders proven to be linked to the HLA locus, including MS.

Abbreviations

- CNVs:

-

Copy number variations

- CGH:

-

Comparative genomic hybridization

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- VM:

-

Venous malformations

- EDSS:

-

Expanded disability status scale

- MS-SS:

-

Multiple sclerosis severity score

- CCSVI:

-

Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency

- VHISS:

-

Venous haemodynamic insufficiency severity score

- VH:

-

Venous haemodynamic criteria.

References

Oksenberg JR, Baranzini SE, Sawcer S, Hauser SL: The genetics of multiple sclerosis: SNPs to pathways to pathogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2008, 9: 516-26. 10.1038/nrg2395.

Compston A, Coles A: Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2002, 359: 1221-31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08220-X.

Frohman EM, Racke MK, Raine CS: Multiple sclerosis--the plaque and its pathogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354: 942-55. 10.1056/NEJMra052130.

Comabella M, Craig DW, Camiña-Tato M, Morcillo C, Lopez C, Navarro A, Rio J, BiomarkerMS Study Group, Montalban X, Martin R: Identification of a novel risk locus for multiple sclerosis at 13q31.3 by a pooled genome-wide scan of 500,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms. PLoS One. 2008, 3: e3490-10.1371/journal.pone.0003490.

Ramagopalan SV, McMahon R, Dyment DA, Sadovnick AD, Ebers GC, Wittkowski KM: An extension to a statistical approach for family based association studies provides insights into genetic risk factors for multiple sclerosis in the HLA-DRB1 gene. BMC Med Genet. 2009, 10: 10-10.1186/1471-2350-10-10.

Chao MJ, Barnardo MC, Lincoln MR, Ramagopalan SV, Herrera BM, Dyment DA, Montpetit A, Sadovnick AD, Knight JC, Ebers GC: HLA class I alleles tag HLA-DRB1*1501 haplotypes for differential risk in multiple sclerosis susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008, 105: 13069-74. 10.1073/pnas.0801042105.

Aulchenko YS, Hoppenbrouwers IA, Ramagopalan SV, Broer L, Jafari N, Hillert J, Link J, Lundström W, Greiner E, Dessa Sadovnick A, Goossens D, Van Broeckhoven C, Del-Favero J, Ebers GC, Oostra BA, van Duijn CM, Hintzen RQ: Genetic variation in the KIF1B locus influences susceptibility to multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 1402-3. 10.1038/ng.251.

Cronin S, Blauw HM, Veldink JH, van Es MA, Ophoff RA, Bradley DG, Berg van den LH, Hardiman O: Analysis of genome-wide copy number variation in Irish and Dutch ALS populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2008, 17: 3392-8. 10.1093/hmg/ddn233.

Blauw HM, Veldink JH, van Es MA, van Vught PW, Saris CG, Zwaag van der B, Franke L, Burbach JP, Wokke JH, Ophoff RA, Berg van den LH: Copy-number variation in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a genome-wide screen. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7: 319-26. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70048-6.

International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium, Hafler DA, Compston A, Sawcer S, Lander ES, Daly MJ, De Jager PL, de Bakker PI, Gabriel SB, Mirel DB, Ivinson AJ, Pericak-Vance MA, Gregory SG, Rioux JD, McCauley JL, Haines JL, Barcellos LF, Cree B, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL: Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357: 851-62. 10.1056/NEJMoa073493.

International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium (IMSGC): Refining genetic associations in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7: 567-9. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70122-4.

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium: Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007, 447: 661-78. 10.1038/nature05911.

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium: Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 1329-37. 10.1038/ng.2007.17.

Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, Qi Y, Scherer SW, Lee C: Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004, 36: 949-51. 10.1038/ng1416.

Shoichet SA, Waibel S, Endruhn S, Sperfeld AD, Vorwerk B, Müller I, Erdogan F, Ludolph AC, Ropers HH, Ullmann R: Identification of candidate genes for sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by array comparative genomic hybridization. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009, 10: 162-9. 10.1080/17482960802535001.

Zamboni P, Galeotti R, Menegatti E, Malagoni AM, Tacconi G, Dall'Ara S, Bartolomei I, Salvi F: Chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009, 80: 392-9. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.157164.

Zamboni P, Menegatti E, Bartolomei I, Galeotti R, Malagoni AM, Tacconi G, Salvi F: Intracranial venous haemodynamics in multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2007, 4: 252-8. 10.2174/156720207782446298.

Zamboni P, Menegatti E, Galeotti R, Malagoni AM, Tacconi G, Dall'Ara S, Bartolomei I, Salvi F: The value of cerebral Doppler venous haemodynamics in the assessment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009, 282: 21-7. 10.1016/j.jns.2008.11.027.

Zamboni P, Consorti G, Galeotti R, Gianesini S, Menegatti E, Tacconi G, Carinci F: Venous Collateral Circulation Of The Extracranial Cerebrospinal Outflow Routes. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2009

Franceschi C: The unsolved puzzle of multiple sclerosis and venous function. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009, 80: 358-10.1136/jnnp.2008.168179.

Zamboni P: Iron-dependent inflammation in venous disease and proposed parallels in multiple sclerosis. J R Soc Med. 2006, 99: 589-93. 10.1258/jrsm.99.11.589.

Zivadinov R, Bakshi R: Role of MRI in multiple sclerosis II: brain and spinal cord atrophy. Front Biosci. 2004, 9: 647-64. 10.2741/1262.

Hammond KE, Metcalf M, Carvajal L, Okuda DT, Srinivasan R, Vigneron D, Nelson SJ, Pelletier D: Quantitative in vivo magnetic resonance imaging of multiple sclerosis at 7 Tesla with sensitivity to iron. Ann Neurol. 2008, 64: 707-13. 10.1002/ana.21582.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, Filippi M, Hartung HP, Kappos L, Lublin FD, Metz LM, McFarland HF, O'Connor PW, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Thompson AJ, Weinshenker BG, Wolinsky JS: Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the "McDonald Criteria". Ann Neurol. 2005, 58: 840-6. 10.1002/ana.20703.

Kurtzke JF: Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983, 33: 1444-52.

Roxburgh RH, Seaman SR, Masterman T, Hensiek AE, Sawcer SJ, Vukusic S, Achiti I, Confavreux C, Coustans M, le Page E, Edan G, McDonnell GV, Hawkins S, Trojano M, Liguori M, Cocco E, Marrosu MG, Tesser F, Leone MA, Weber A, Zipp F, Miterski B, Epplen JT, Oturai A, Sørensen PS, Celius EG, Lara NT, Montalban X, Villoslada P, Silva AM, et al: Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score: using disability and disease duration to rate disease severity. Neurology. 2005, 64: 1144-51.

Pachner AR, Steiner I: The multiple sclerosis severity score (MSSS) predicts disease severity over time. J Neurol Sci. 2009, 278: 66-70. 10.1016/j.jns.2008.11.020.

Menegatti E, Zamboni P: Doppler haemodynamics of cerebral venous return. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2008, 5: 260-5. 10.2174/156720208786413442.

Agilent Technologies eArray. [https://earray.chem.agilent.com/earray]

Bovolenta M, Neri M, Fini S, Fabris M, Trabanelli C, Venturoli A, Martoni E, Bassi E, Spitali P, Brioschi S, Falzarano MS, Rimessi P, Ciccone R, Ashton E, McCauley J, Yau S, Abbs S, Muntoni F, Merlini L, Gualandi F, Ferlini A: A novel custom high density-comparative genomic hybridization array detects common rearrangements as well as deep intronic mutations in dystrophinopathies. BMC genomics. 2008, 9: 572-10.1186/1471-2164-9-572.

Gene Expression Omnibus. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/]

Database of Genomic Variants. [http://projects.tcag.ca/variation]

Lincoln MR, Ramagopalan SV, Chao MJ, Herrera BM, Deluca GC, Orton SM, Dyment DA, Sadovnick AD, Ebers GC: Epistasis among HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1 loci determines multiple sclerosis susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106: 7542-7.

Craelius W, Migdal MW, Luessenhop CP, Sugar A, Mihalakis I: Iron deposits surrounding multiple sclerosis plaques. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982, 106: 397-9.

Levine SM, Chakrabarty A: :The role of iron in the pathogenesis of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004, 1012: 252-66. 10.1196/annals.1306.021.

Singh AV, Zamboni P: Anomalous Venous Blood Flow And Iron Deposition In Multiple Sclerosis. J Cer Blood Flow Met. 2009, 29 (12): 1867-78. 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.180.

Loscalzo J, Kohane I, Barabasi AL: Human disease classification in the postgenomic era: a complex systems approach to human pathobiology. Mol Syst Biol. 2007, 3: 124-10.1038/msb4100163.

Horton R, Gibson R, Coggill P, Miretti M, Allcock RJ, Almeida J, Forbes S, Gilbert JG, Halls K, Harrow JL, Hart E, Howe K, Jackson DK, Palmer S, Roberts AN, Sims S, Stewart CA, Traherne JA, Trevanion S, Wilming L, Rogers J, de Jong PJ, Elliott JF, Sawcer S, Todd JA, Trowsdale J, Beck S: Variation analysis and gene annotation of eight MHC haplotypes: the MHC Haplotype Project. Immunogenetics. 2008, 60: 1-18. 10.1007/s00251-007-0262-2.

Chaudhuri D, Suriano R, Mittelman A, Tiwari RK: Targeting the immune system in cancer. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2009, 10 (2): 166-84. 10.2174/138920109787315114.

Karapanagiotou EM, Syrigos K, Saif MW: Heat shock protein inhibitors and vaccines as new agents in cancer treatment. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009, 18 (2): 161-74. 10.1517/13543780802715792.

Yordy JS, Moussa O, Pei H, Chaussabel D, Li R, Watson DK: SP100 inhibits ETS1 activity in primary endothelial cells. Oncogene. 2005, 24 (5): 916-31. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208245.

Lincoln MR, Ramagopalan SV, Chao MJ, Herrera BM, Deluca GC, Orton SM, Dyment DA, Sadovnick AD, Ebers GC: Epistasis among HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1 loci determines multiple sclerosis susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106 (18): 7542-7.

Podojil JR, Miller SD: Molecular mechanisms of T-cell receptor and costimulatory molecule ligation/blockade in autoimmune disease therapy. Immunol Rev. 2009, 229 (1): 337-55. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00773.x.

Wieder T, Braumüller H, Kneilling M, Pichler B, Röcken M: T cell-mediated help against tumors. Cell Cycle. 2008, 7 (19): 2974-7.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2350/11/64/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank Hilarescere Foundation for supporting the research program on CCSVI and MS at the University of Ferrara, Italy. The MS-CGH array has been patented, IP number n. TO2009A000672.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MB designed and validated the custom CGH-array; MN contributed to the patients' genomic analysis; AY performed the networking genes pathway analysis via Ariadne software; FS studied the patients from neurological aspects; AB performed HLA genotyping, DG collected DNA samples, AL and PZ planned, performed and interpreted the vascular studies; FG scientifically revised the manuscript; AF designed the study and wrote the manuscript, AF and PZ revised the manuscript and approved the final version. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12881_2009_625_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Patients Population Demographics, Clinical Parameters, HLA DRB1 haplotype and CNVs number. Top table: EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale (the most widely-used disability score). MS-SS: Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score (score expressing the tendency of MS to progress over the years). VH: Venous Haemodynamic Criteria (number of anomalous haemodynamic parameters detected by colour Doppler protocol), VHISS: venous haemodynamic insufficiency severity score [34]. VM: venous malformations (number of stenosing malformations affecting the cerebrospinal veins, detected by selective venography). CNVs: copy number variations. Bottom table: Summary of clinical characteristics, HLA DRB1*5 typing and number of CNVs of each patient studied. (DOC 62 KB)

12881_2009_625_MOESM2_ESM.XLS

Additional file 2: Genomic distribution of CNVs for each patient. Genomic coordinates of the known CNVs identified for each patient. Column F shows the genes where any CNVs are localized and column H the identification number of known CNVs as described in the database of Genomic Variants. (XLS 44 KB)

12881_2009_625_MOESM3_ESM.PNG

Additional file 3: CGH profile of the HLA locus. Example of a CGH profile in patient PF, showing duplications (red dots) and deletions (green dots)- Light blue bars in the lower part of the figure represent genes, while the known polymorphic CNVs are reported with their identification number (Database of Genomic Variants at http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/). Below is shown the map in Mbases of the locus with the distribution and density of CNVs. (PNG 579 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferlini, A., Bovolenta, M., Neri, M. et al. Custom CGH array profiling of copy number variations (CNVs) on chromosome 6p21.32 (HLA locus) in patients with venous malformations associated with multiple sclerosis. BMC Med Genet 11, 64 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-11-64

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-11-64