Abstract

Background

Serological study of human papillomavirus (HPV)-antibodies in order to estimate the HPV-prevalence as risk factor for the development of HPV-associated malignancies in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive men.

Methods

Sera from 168 HIV-positive men and 330 HIV-negative individuals (including 198 controls) were tested using a direct HPV-ELISA specific to HPV-6, -11, -16, -18, -31 and bovine PV-1 L1-virus-like particles. Serological results were correlated with the presence of HPV-associated lesions, the history of other sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and HIV classification groups.

Results

In HIV-negative men low risk HPV-antibodies were prevailing and associated with condylomatous warts (25.4%). Strikingly, HIV-positive men were more likely to have antibodies to the high-risk HPV types -16, -18, -31, and low risk antibodies were not increased in a comparable range. Even those HIV-positive heterosexual individuals without any HPV-associated lesions exhibited preferentially antibody responses to the oncogenic HPV-types (cumulative 31.1%). The highest antibody detection rate (88,8%) was observed within the subgroup of nine HIV-positive homosexual men with anogenital warts. Three HIV-positive patients had HPV-associated carcinomas, in all of them HPV-16 antibodies were detected. Drug use and mean CD4-cell counts on the day of serologic testing had no influence on HPV-IgG antibody prevalence, as had prior antiretroviral therapy or clinical category of HIV-disease.

Conclusion

High risk HPV-antibodies in HIV-infected and homosexual men suggest a continuous exposure to HPV-proteins throughout the course of their HIV infection, reflecting the known increased risk for anogenital malignancies in these populations. The extensive increase of high risk antibodies (compared to low risk antibodies) in HIV-positive patients cannot be explained by differences in exposure history alone, but suggests defects of the immunological control of oncogenic HPV-types. HPV-serology is economic and can detect past or present HPV-infection, independently of an anatomical region. Therefore HPV-serology could help to better understand the natural history of anogenital HPV-infection in HIV-positive men in the era of antiretroviral therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Venereal diseases, sexual promiscuity and receptive anal intercourse are associated with an increased risk for anal cancer. Particularly, in HIV-infected individuals an alarming increase of HPV-associated malignancies has to be expected [1–3]. Recent data from the US AIDS-cancer registry reveal for women and men with HIV-infection 6.8 and 37 times greater relative risks for anal cancer compared to respective control populations. It appears, that potent antiretroviral therapy has limited effect in inducing regression of HPV-lesions and HPV-DNA tends to persist in the anorectal canal [4]. Progression from high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) to cancer may take as long as 10 or more years in HIV-seronegative individuals. Therefore it is hypothesised, that in the era of antiretroviral therapy the incidence of anogenital cancer in HIV-positive patients will increase as consequence of prolonging survival combined with persistent deviations of the immune system.

A breakthrough in the prophylaxis of cervical cancer has been achieved by introduction of cervical cytological testing described in the report of Papanicolaou and Trout [5]. A 53% reduction in cervical cancer mortality was reported in Sweden [6]. and Quinn estimated 1997 that without screening there might have been 800 more deaths in England from cervical cancer in women under 55 years of age [7]. Nowadays, high risk lesions could also be identified by detecting viral HPV-DNA in cervical smears [8].

The incidence of anal cancer in HIV-positive men will be probably higher than the incidence of cervical cancer prior the use of cervical cytology screening [9]. However, even in risk groups – such as HIV-positive homosexual men – there are no such standard screening and management procedures established for the anus. Routine cytological screening has to await an effective proved intervention for anal intraepithelial neoplasia [10]. Antibodies to HPV capsid antigens are reliable markers for cumulative HPV exposure and have been used in prospective studies, that linked HPV infection to cancers [11]. Therefore we investigated HPV-antibodies in order to estimate the HPV-prevalence as risk factor for the development of HPV-associated malignancies, particularly, in HIV-positive men.

Methods

HIV-positive patients

The AIDS clinic at the University of Innsbruck is the only centre for patients with HIV/AIDS of the Austrian Tyrol. More than 95% of the Tyrolean AIDS-patients with AIDS reported to the health authorities are in treatment at this clinic. One hundred and sixty-eight HIV-positive men (aged 23 to 61 years, median 43) were regularly seen at our department and sera from the year 1998 were available from all of the patients. Fifty-nine were homosexuals (35.1%), previous or present intravenous drug use was known from 60 men (35,7%) and blood products were the source of HIV-infection in 8 men (4,7%). The remaining 41 men (24.5%) were infected by heterosexual contacts or the transmission route was unknown.

The CD4-cell counts at the time of serum collection were: 42 patients <200/μl, 61 patients 200–400/μl, 65 patients >400/μl. Sixty (35.8%) patients were according to the classification of the Centre of Disease Control (CDC) in asymptomatic disease stage CDC A, fifty-four (32.1%) in mild symptomatic CDC B and fifty-four (32.1%) in CDC C. Stage CDC C is equivalent to AIDS. Antiretroviral therapy at the time of serum collection (1998) was already initiated in 96 (57.1%) individuals. HPV-associated diseases in HIV-positive men were present in 28 (16.6%) patients: 25 (14.8%) men had condylomatous warts and 3 (1.7%) invasive carcinomas (2 anal and 1 rectal squamous cell carcinoma). Two of this 3 carcinoma patients were homosexuals. History for other sexually transmitted diseases (STD) was positive in 42 (25%) men, being treated for genital herpes, gonorrhoea, clamydia or syphilis.

HIV-negative patients with HPV lesions

HIV-negative individuals with HPV-associated diseases studied were 55 men with condylomatous genital warts and 7 men with genitoanal cancer. An additional group consisted of 70 nonpregnant HIV-negative women with external condylomatous warts but normal pap smears, in order to allow comparison of seroresponses in women and men.

Control patients

There were two groups of male HIV-negative patients as follows: First, 98 heterosexual men randomly chosen from patients visiting the dermatological outpatient clinic representing a cross-section of men attending a university hospital in Austria, with no bias as to social or economic status. The reasons for consulting the clinic were skin disorders (e.g. eczema, psoriasis). Patients with drug abuse, homosexuality, malignancies, existing or previous HPV-related diseases or other STD were excluded (questionnaire). The second control group consisted of 100 blood donors being routinely screened for infectious diseases or immune activation (serum neopterin level) but without available information concerning genital warts or sexual behaviour.

The age of all 260 HIV-negative men (median age 42,5 years) did not differ significantly compared with the HIV-positive patients.

HIV-serology and sampling

Sera were screened for HIV antibodies using the Enzygnost Anti HIV 1/2 ELISA (Behring, Germany) and confirmed by Western Blot (Du Pont de Nemours, Germany, or Biotechnologies, Singapore) in at least two different samples. Serum samples for HPV analysis obtained from all individuals were frozen, preserved at -80°C and used for later HPV serology.

HPV-ELISA

Baculovirus-expressed HPV-6, -11, -16, -18, -31 and BPV-1 L1-virus-like particles (VLPs) were used as antigens in direct ELISAs as described previously [12]. Briefly, VLPs 1:100 diluted in PBS were attached to wells of round bottom ELISA plates (Nunc™ Brand Products and Petra Plastic 96 rounded wells γ-sterilized Typ F – ELISA 11041 E) by incubating 90 μl of VLP-solution/well at room temperature for 45 min. VLP-free PBS-incubated wells were used as negative control wells. All plates were washed three times with PBS (SLT Labinstruments 812 SW2) and were incubated with 200 μl milk-buffer (1 g Fixmilch Instant® + 20 ml Dulbecco's® phosphate buffered saline) / well for 30 min (room temperature). Patient sera were heat-inactivated at 56°C for 30 min and used at a final serum dilution of 1:100. Each patient's serum (25 μl) and positive and negative controls were tested in duplicate wells and incubated for 1 h and washed again three times. Monoclonal antibodies (100 μl) corresponding to VLP-types (positive control wells) were diluted with 5% milk-PBS (final dilution of 1:200). Subsequently the wells were incubated with goat anti-human IgG (1:10000), and RαM (1:1000) antibodies (Sigma, St. Louis). After incubation for 30 min. (room temperature) the wells were washed three times and substrate (TRIS-puffer with p-Nitrophenylphosphate tablets) was added. Optical densities (OD's) were read on a microplate reader (SLT Labinstruments 400 ATC, Salzburg, Austria; Software Easy-Fit) at 405 nm 30, 60, and 90 min after adding substrate. Means and standard deviations (SD) of duplicate wells were calculated as final OD values for each serum sample. There was a high correlation of paired values and there were only rarely duplicates which were not consistent with each other. These tests were repeated. The coefficient of variation of selected sets of samples for each ELISA experiment ranged between 0.7 and 4%. In addition in subsets of more than 100 patient sera reproducibility was at least 94%.

Statistical analysis

In all experiments patient and control sera were analysed together. Means and SD of ELISA absorbency values of the control group (dermatology clinic patients) were used statistically to define positive and negative patient sera for each target antigen (HPV-6, -11, -16, -18, -31 and bovine PV-1). Individual values in the control group exceeding the mean + 3 SD were excluded and the remaining readings were averaged again until no further values exceeded the recalculated mean + 3 SD. Samples with values greater than the recalculated final mean + 3 SD were designated positive for reactivity to the appropriate antigen in the current experiment. For scalar variables, the non parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis, because group OD values had an asymmetric distribution; Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. P < 0.05 (two tailed) was considered statistically significant. All calculations were done with SheePS Counting Software (SPSS) 7.0 for Windows 95.

Results

In general, the prevalence of HPV-antibodies was significantly lower in men compared to women. Data for HIV-negative patients with condylomatous warts are shown in table 1.

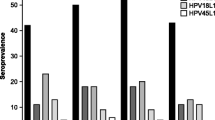

HPV-ELISA; comparison of HIV-positive and HIV-negative men

Both HIV-negative male control groups (patients of dermatological clinic or blood donors) had similar low HPV antibody rates: Reactivity to HPV-6/ -11 and -16/ -18/ -31 was observed respectively in 10,2% / 5,1% and 5,1% / 5,1% / 6,1% of patients without HPV-lesions (dermatology clinic patients). HIV-positive men were significantly more likely than HIV-negative men to have detectable levels of antibodies in particular to the high-risk VLPs (HPV types -16, -18, -31). In contrast, low risk antibodies were only increased to a lesser extend. In 168 HIV-positive men IgG reactivity to HPV-6/ -11 and -16/ -18/ -31 was observed in 19% / 16% and 27,9% / 19,6% / 20,2%. Overall seropositivity rates are summarised in table 2. HIV-positive men with warts were more likely to have high risk HPV-antibodies (16/25 = 64%) compared to all HIV-positive men without warts (50/143 = 34%): p = 0.0078, Odds ratio (95% CI), 3.3 (0.18–0.79). In HIV-negative men, particularly in those with condylomatous warts, mainly low risk HPV-antibodies were detected, whereas in all groups of HIV-positive men high-risk HPV antibody were more prevalent. In HIV-positive men with benign genital warts and even in men without any clinical evident genitoanal lesions the cumulative high risk antibody seroprevalence was much higher than expected. This phenomenon remained evident analysing the complete cohorts of patients: The risk for HIV-positive men (n = 168) in comparison to HIV-negative men (n = 260) to have detectable high risk-HPV antibodies was much higher (O.R. = 5.343; 95% CI: 3,27–8.71) than the risk to have HPV-low risk antibodies (O.R. = 2.075; 95% CI: 1.25–3.42). No significant reactivities were seen with the bovine PV control antigen.

HPV-ELISA; analyses within the HIV-positive cohort

Only three HIV-positive patients had HPV-related invasive carcinomas. In all of them HPV-16 antibodies were detected, whereas in 7 HIV-negative men with anal cancers only 1 had HPV-16 antibodies. The number of patients with malignancies was to small for statistical analysis. Data of cancer patients are shown in table 3. Clinical detection of warts in HIV-positive patients was associated with low risk HPV-antibodies (table 2), but statistics revealed a trend only (p = 0.07). High-risk HPV-IgG antibodies were detected more frequently despite absence of anogenital carcinoms: high-risk antibodies were detected in 16 of 25 HIV-infected men with benign condylomatous warts (64%) and in 48 of 140 men without warts (34%). The most prevalent antibody in HIV-positive men was reactive with HPV-16 VLPs and was detected in 20.7 % of 140 men without any HPV-lesions, reached a percentage of 52% in 25 men with benign condylomatous warts and 100 % in 3 men with anal carcinomas. Antibody reactivities to different HPV-types are shown in table 4. The highest antibody detection rate (88,8%) was observed with the 3 high-risk HPV-types together within the subgroup of nine HIV-positive homosexual men with genitoanal warts. Even homosexual men without HPV-lesions (n = 50) had HPV-antibodies in 50%. Drug users (all of them heterosexuals) were the subgroup with the lowest HPV-antibody prevalence, although drug abuse is a well-known single risk factor for STD. Mean CD4-cell counts on the day of serologic testing had no influence on HPV-IgG antibody prevalence, as had prior antiretroviral therapy or clinical category of HIV-disease (table 5).

HPV-ELISA; type specificity and double reactivity

In HIV-positive men Ig reactivity to more than one high-risk or low-risk HPV-type was found in the range of 30% of positive sera. Preferentially double reactivity with the closely related VLP types HPV-6 and -11 were seen (42,6%). HPV-16 and HPV-18 double reactivity was detected in 31% and with the types HPV-16 and HPV-6 in 25% only. Double reactivity within the high risk HPV-antibody group appeared to be associated with a history of other STDs than warts (genital herpes, gonorrhoea, clamydia or syphilis): In 42 HIV-positive men with STDs 7 of 21 (33.3%) HPV-positive sera were HPV-16/18 double reactive; In 126 HIV-positive men without such STDs 11 of 56 (19.6%) Statistics revealed a trend only (p = 0.0539).

Discussion

Among women and men the incidence of anal cancer has increased in recent decades. Anal cancer is an infectious disease associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) exposure influenced by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic [13]. High risk HPV-DNA, which is known to cause cancer of the cervix, was found in 84% of anal cancer tissue specimens [14]. The present study demonstrates, that HIV-infected men are able to generate a vigorous anti-HPV serological response against these infections. This is not surprising since in HIV-positive patients the humoral immunity is much less impaired compared to cellular immune functions. In addition, HPV has probably been acquired many years before severe deficiencies of immune functions in AIDS patients develop.

In HIV-positive individuals the seroreactivity rate was lower in men than in women compared to our recently published data on IgG reactivity to HPV-6/ -11 and -16/ -18/ -31 in 19% / 31% and 49% / 30% / 24% in HIV-positive women, respectively [12]. In this previous study HPV-seropositivity in HIV-positive women was even higher than in 48 HIV-negative women with cervical intraepithelial lesions or cancer exhibiting percentages as follows: 8% / 2% and 31% / 15% / 15%. The phenomenon of lower HPV-seroreactivity in men was also seen in the present study comparing HIV-negative men and women with condylomatous warts. In general, men appear to be less likely to be HPV-seropositive, despite of exhibiting increased risk behaviour [15]. Nevertheless, HPV-antibody detection in men was associated with HPV-associated lesions and/or HIV-seropositivity. The most striking result was the observation, that even those HIV-positive individuals without clinical evident HPV-associated lesions exhibited antibody responses preferentially to oncogenic HPV-types, whereas the prevalence of low risk antibodies was only moderately increased. This observation strongly suggests that – at least in part – immune deviations associated with HIV rather than differences in exposure history contributed to the observed discrepant low risk and high risk HPV sero-prevalences in HIV-positive individuals.

The highest HPV-seroprevalence was observed in the subgroup of homosexual men. This prevalence was in the range of a previous study on HPV-6 and HPV-16 antibodies in men [16]. In addition, Hagensee et al have shown a similar seroprevalence in homosexuals with or without HIV. The phenomenon that high-risk HPV-antibodies are much more prevalent than low-risk antibodies in HIV-positive and/or homosexual individuals reflects obviously the known increased risk for anogenital malignancies in these populations. It is interesting to note, though, that in our HIV-negative men high risk HPV-antibodies were not a reliable marker for anogenital cancer, although the 3 tested high risk HPV types (16, 18, 31) normally comprise more than 80% of oncogenic HPV-types e.g. detected in cervical carcinomas in Europe: Only 2 of 7 HIV-negative cancer patients had these high risk antibodies, whereas in the small group of 3 HIV-positive cancer patients all had antibodies. In risk populations a further increase of anal carcinomas has to be expected in the future, since at the end of the study in 2002 (including a follow up period of 3–4 years) three HIV-positive men had already HPV-related carcinomas. This rate would be equivalent to an incidence of 170 per 100 000.

The rate of antibody double reactivities with more than one HPV-type was in the range as observed in HIV-positive women [12], suggesting comparable exposure to various HPV-types in women and men. Double reactivity could reflect crossreactivity or infection with multiple HPV types, but at least in part the data indicate infection with multiple HPV-types, since we have previously performed competition experiments and analyses with monoclonal mouse antibodies showing, that type specific IgG antibodies exist, which discriminate even the closely related HPV types -6 and -11 [17]. In the present study there was accordingly a trend for double reactivity in homosexuals and in HIV-positive men with histories of STDs suggesting infections with multiple HPV types.

The extraordinary high prevalence of high risk HPV-antibodies exceeding the low risk HPV-antibody prevalence in HIV-positive individuals needs to be interpreted. HIV-infected individuals are obviously not able to sufficiently control particularly high risk HPV by cellular immune mechanisms resulting in prolonged persistence of HPV-DNA as demonstrated [18]. The occurrence of complete life cycles of HPV and subsequent capsid expression is thought to be the primary determinant of a detectable humoral response, reflecting lifetime cumulative exposure to HPV [19]. Seropositivity is probably a better marker for past sexual behaviour than presence of HPV-DNA [20]. Therefore, our data suggest that HIV-positive men are intensely exposed to high-risk HPV proteins throughout the natural course of their HIV infection. This persistence of oncogenic HPV-types could be one explanation for the association of HIV with HPV-associated malignancies. An interaction of HIV and HPV and local factors are probably also involved in the carcinogenesis in HIV-positive individuals [21, 22].

Dysplasia may also develop in visually normal anal mucosa [23], but routine anal cytology is not established. In addition, women – despite of the absence of evidence for cervical disease – may also be at risk for anal disease, in a region were HPV-screening is usually not performed. HPV-serology could be used for risk assessment in HIV-positive patients to circumvent these problems, since serology is convenient, economic and can detect past and present HPV-infection, independently of an anatomical region. In HIV-negative women it has been shown, that HPV-antibodies in prediagnostic sera indicate risk for occurrence of cervical cancer: the relative risk was highest (odds ratio = 7,5) in patients with high antibody levels [24].

Conclusions

We conclude, that the high seroprevalence of HPV-antibodies in HIV-positive men reflects a high lifetime cumulative exposure to oncogenic HPV-types. This may be due to risky sexual behaviour in combination with defects of the immunological control of HPV. The serological data are in line with published results on anal intraepithelial neoplasia associated with HPV-DNA, which was demonstrated in 84 % among HIV-positive homosexual men [25]. A role of HPV-serology for diagnostic strategies in HIV-infected individuals remains to be determined, but the presented serological data will be the basis for a close follow up in the next decade, in order to better understand the natural history of anogenital HPV-infection in HIV-positive men in the era of antiretroviral therapy. HIV-infected patients may also be candidates for prophylactic HPV-vaccination strategies, since in these individuals a humoral immune response to HPV occurs.

References

Palefsky JM: Human papillomavirus infection and anogenital neoplasia in human immunodeficiency virus-positive men and women. J Natl Cancer Inst monogr. 1998, 23: 14-20.

Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, Jay N: Prevalence and risk factors for human papillomavirus infection of the anal canal in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative men. J Infect Dis. 1998, 177: 361-367.

Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Ralston ML, Jay N, Berry JM, Darragh TM: High incidence of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions among HIV-positive and HIV-negative homosexual and bisexual men. AIDS. 1998, 12: 495-503. 10.1097/00002030-199805000-00011.

Lampinen TM, Critchlow CW, Kuypers JM, HUrt CS, Nelson PJ, Hawes SE, Coombs RW, Holmes KK, Kiviat NB: Association of antiretroviral therapy with detection of HIV-1RNA and DNA in the anorectal mucosa of homosexual men. AIDS. 2000, 14: F69-75. 10.1097/00002030-200003310-00001.

Papanicolaou GN, Trout HE: Diagnosis of uterine cancer by vaginal smears. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. 1943

Mahlck CG, Jonsson H, Lenner P: Pap smear screening and changes in cervical cancer mortality in Sweden. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1994, 44: 267-72.

Quinn M, Babb P, Jones J, Allen E: Effect of screening on incidence of and mortality from cancer of cervix in England: evaluation based on routinely collected statistics. BMJ. 1999, 318: 904-908.

Ledger WJ, Jeremias J, Witkin SS: Testing for high-risk human papillomavirus types will become a standard of clinical care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000, 182: 860-865.

Goedert JJ, Cote TR, Virgo P, Scoppa SM, Kingma DW, Gail MH, Jaffe ES, Biggar RJ: Spectrum of AIDS-associated malignant disorders. Lancet. 1998, 351: 1833-1839. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09028-4.

Martin F, Bower M: Anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV positive people. Sex Trans Inf. 2001, 77: 327-331. 10.1136/sti.77.5.327.

Mork J, Lie AK, Glattre E, Hallmans G, Jellum E, Koskela P, Möller B, Pukkala E, Schiller JT, Youngman L, Lehtinen M, Dillner J: Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344: 1125-1131. 10.1056/NEJM200104123441503.

Petter A, Heim K, Guger M, Ciresa-König A, Christensen N, Sarcletti M, Wieland U, Pfister H, Zangerle R: Specific serum IgG, IgM and IgA antibodies to human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, 18 and 31 virus-like particles in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive women. J Gen Virol. 2000, 1: 701-708.

Chopra FK, Tyring KS: The Impact of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus on the Human Papillomavirus Epidemic. Arch Dermatol. 1997, 133: 629-633. 10.1001/archderm.133.5.629.

Frisch M, Glimelius B, Van den Brule AJC, Wohlfahrt J, Meier C, Walboomers J, Goldman S, Svensson C, Adami HO, Melbye M: Sexually transmitted Infection as a Cause of Anal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997, 337: 1350-1358. 10.1056/NEJM199711063371904.

Slavinsky J, Kissinger P, Burger L, Boley A, DiCarlo RP, Hagensee ME: Seroepidemiology of low and high oncogenic risk types of human papillomavirs in a predominantly male cohort of STD clinic patients. Int J STD AIDS. 2001, 12: 516-523. 10.1258/0956462011923615.

Hagensee ME, Kiviat N, Critchlow CW, Hawes SE, Kuypers J, Holte S, Galloway DA: Seroprevalence of Human Papillomavirus Types 6 and 16 Capsid Antibodies in Homosexual Men. J Infect Dis. 1997, 176: 625-631.

Heim K, Christensen ND, Höpfl R, Wartusch B, Pinzger G, Zeimet A, Baumgartnder P, Kreider JW, Dapunt O: Serum IgG, IgM and IgA Reactivity to Human Papillomavirus Types 11 and 6 Virus-like Particles in Different Gynecologic Patient Groups. J Infect Dis. 1995, 172: 395-402.

Sun XW, Kuhn L, Ellerbrock TV, Chiasson MA, Bush TJ, Wright TC: Human papillomavirus infection in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1997, 337: 1343-1349. 10.1056/NEJM199711063371903.

af Geijersstam V, Kibur M, Wang Z, Koskela P, Pukkala E, Schiller J, Lehtinen M, Dillner J: Stability over Time of Serum Antibody Levels to Human Papillomavirus Type 16. J Infect Dis. 1998, 177: 1710-1714.

Olsen AO, Dillner J, Gjoen K, Magnus P: Seropositivity against HPV 16 capsids: a better marker of past sexual behaviour than presence of HPV DNA. Genitourinary Medicine. 1997, 73: 131-135.

Bernard C, Mougin C, Madoz L, Drobacheff C, Van Landuyt H, Laurent R, Lab M: Viral co-infections in human papillomavirus-associated anogenital lesions according to the serostatus for the human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Cancer. 1992, 52: 731-737.

Critchlow CW, Surawicz CM, Holmes KK, Kuypers J, Daling Jr, Hawes SE, Goldbaum GM, Sayer J, Hurt C, Dunphy C, Kiviat NC: Prospective study of high grade anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia in a cohort of homosexual men: influence of HIV infection, immunosuppression and human papillomavirus infection. AIDS. 1995, 9: 1255-1262.

Surawicz CM, Critchlow C, Sayer J, Hurt C, Hawes S, Kirby P, Goldbaum G, Kiviat N: High grade anal dysplasia in visually normal mucosa in homosexual men: seven cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995, 90: 1776-1778.

Shah KV, Viscidi RP, Alberg AJ, Helzlsouer KJ, Comstock GW: Antibodies to human papillomavirus 16 and subsequent in situ or invasive cancer of the cervix. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers and Prev. 1997, 6: 233-237.

Lacey HB, Wilson GE, Tilston P, Wilins EG, Bailey AS, Corbitt G, Green PM: A study of intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV positive homosexual men. Sex Transm Inf. 1999, 75: 172-177.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/3/6/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant P-10896-MED of the Austrian Science Foundation. We like to thank A.B. Jenson and J.T. Schiller for providing us recombinant baculoviruses, N. Christensen for providing monoclonal antibodies and A. Wiedemair for expert technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

RH: study idea, data analysis and interpretation, report writing; AP: handling of serum specimens and patient data. PT: sexual behaviour questionnaire, serum assays, data analysis; MS: assistance with data analysis; AW: supervision of laboratory tests, data analysis in female patients, manuscript review; RZ: interpretation of data, responsible for HIV-positive patients, manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Höpfl, R., Petter, A., Thaler, P. et al. High prevalence of high risk human papillomavirus-capsid antibodies in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive men: a serological study. BMC Infect Dis 3, 6 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-3-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-3-6