Abstract

Background

Nitric oxide (NO) production is increased among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and also among those with tuberculosis (TB). In this study we sought to determine if there was increased NO production among patients with HIV/TB coinfection and the effect of four weeks chemotherapy on this level.

Methods

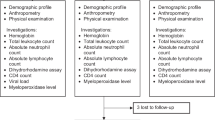

19 patients with HIV/TB coinfection were studied. They were treated with standard four drug antitubercular therapy and sampled at baseline and four weeks. 20 patients with HIV infection, but no opportunistic infections, were disease controls and 20 individuals were healthy controls. Nitrite and citrulline, surrogate markers for NO, were measured spectrophotometrically.

Results

The mean age of HIV/TB patients was 28.4 ± 6.8 years and CD4 count was 116 ± 36.6/mm. Mean nitrite level among HIV/TB coinfected was 207.6 ± 48.8 nmol/ml. This was significantly higher than 99.7 ± 26.5 nmol/ml, the value for HIV infected without opportunistic infections and 46.4 ± 16.2 nmol/ml, the value for healthy controls (p value < 0.01). The level of HIV/TB coinfected NO in patients declined to 144.5 ± 34.4 nmol/ml at four weeks of therapy (p value < 0.05). Mean citrulline among HIV/TB coinfected was 1446.8 ± 468.8 nmol/ml. This was significantly higher than 880.8 ± 434.8 nmol/ml, the value for HIV infected without opportunistic infections and 486.6 ± 212.5 nmol/ml, the value for healthy controls (p value < 0.01). Levels of citrolline in HIV/TB infected declined to 1116.2 ± 388.6 nmol/ml at four weeks of therapy (p value < 0.05).

Conclusions

NO production is elevated among patients with HIV infection, especially so among HIV/TB coinfected patients, but declines significantly following 4 weeks of antitubercular therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nitric oxide (NO) is an free-radical gas and an important biologically active molecule that participates in host defense against microbes, tumor cells and alloantigens.[1] It is synthesized from L- arginine by a family of three enzyme NO synthase (NOS) proteins, two of which are constitutive (type I and III) and one inducible (type II or iNOS).[2] Citrulline is released by the above reaction.[3] NO is readily transformed into nitrite and nitrate which are excreted into the urine. Type II NOS plays a significant role in various inflammatory processes and also in the functioning of the immune system. [4–8]

Production of NO is elevated among patients with HIV infection. [9–11] These levels may, however, be decreased among patients with advanced disease.[12] Elevated levels of NO among patients with HIV/TB coinfection have also been reported. [13–15] The relevance of NO production in HIV infection lies in the ability of the former to modulate the replication of the latter [1, 16, 17]. Further, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Myco. tub.) enhances the replication of HIV.[18, 19] In the presence of elevated NO production and Myco. tub. infection among HIV infected the disease tends to progress more rapidly. It is imperative to treat tuberculosis energetically and remove one of the variables that affect HIV replication.

Use of antitubercular medications has been shown to reduce the level of immune activation in the HIV/TB coinfected. [20] There has been one previous study looking at the level of NO metabolites after chemotherapy in patients with HIV/TB coinfection.[21] In that study untreated HIV positive patients with pulmonary TB did not have increased urinary nitrite/nitrate levels as compared with controls. As opposed to this HIV negative patients with pulmonary TB had higher urinary metabolite levels and when some of them were followed after chemotherapy there was a significant reduction in these levels.[21] In view of the conflicting data regarding NO production following chemotherapy among the HIV/TB coinfected, we carried out this study to determine if NO production, as measured by its surrogate markers nitrite and citrulline, is elevated among patients with HIV/TB coinfection and if it changes following four weeks of anti-tubercular therapy.

Methods

Patients

Nineteen patients with HIV infection who were diagnosed on the basis of positivity on a panel of three ELISA's and documented to have active TB as shown by AFB positivity were included in the study. They were administered antitubercular therapy (Rifampicin, INH, Ethambutol and Pyrazinamide) in doses appropriate for weight. Blood samples in these cases were taken at the start and at the end of 4 weeks of therapy, which was continued as per standard guidelines. Twenty patients with HIV infection but with no opportunistic infection were studied as disease controls. The latter was ruled out by absence of clinical features of any opportunistic infection and normal hemogram, routine biochemical parameters and chest x-ray. In addition, 20 healthy individuals served as controls.

Nitrite and citrulline measurement

Measurement of NO production in vivo is difficult because of its short half-life and the need for specialised equipment that uses chemiluminescence detection. Consequently, nitrite and citrulline levels were used as surrogate markers for estimating NO production. Nitrite and citrulline were measured in the serum by methods described previously.[22, 23] Samples were stored at -20º C until analysis. For nitrite estimation, 100 ul of serum was reacted with 100 ul of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilide (w/v) in 5% o-phosphoric acid and 0.1% N-1 (napthyl ethylene diamine dihydrochloride and 2% H3PO4). Absorbance was read at 546 nm. Sodium nitrate (10–100 nmol) was used as standard. Citrulline was measured in serum by taking 100 ul of serum, diluting it 20 fold, and deproteinizing it using 0.5 ml of 25% tricarboxylic acid solution. To 0.5 ml of clear supernatant so obtained by centrifugation, 1.5 ml of chromogenic solution was added, mixed vigorously and boiled at 1000 C for 5 min. The tubes were cooled to room temperature and absorbance was read at 530 nm. DL-citrulline (25–300 nmol) was used as standard.

CD4 counts

To determine CD4+ T cell population, 10 ul of anti-human CD4-FITC (Sigma Immunochemicals) was added to 100 ul of whole blood and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. At the end of the incubation, lysing solution was added and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The washed and fixed cells were then analyzed on the flowcytometer (FACScan, Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Ten thousand cells were computed and analyzed using Cell Quest program. Dead cells were excluded by forward and side scatter gating. Statistical markers were set using irrelevant isotype-matched controls as reference.

Statistical analysis

The results in the groups were normally distributed as shown by Shapiro-Wilk W test and were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated to determine correlation between serum level of nitrite and citrulline and CD4 counts. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinical profile of the two groups of patients and healthy individuals is shown in Table 1. The patients were both out patients and hospitalized ones. They were well matched for age and sex and none of them had evidence of renal insufficiency as shown by normal urine examination and normal blood urea and creatinine values. The mean CD4 counts of HIV/TB coinfected were significantly lower than those of patients with HIV infection alone (p < 0.05).

Serum nitrite levels are shown in figures 1 and 2. Mean nitrite levels among the HIV/TB coinfected were 207.6 ± 48.8 nmol/ml and in those with HIV infection alone these were 99.7 ± 26.5 nmol/ml. Healthy controls had mean nitrite levels of 46.4 ± 16.2 nmol/ml. The levels among the HIV/TB coinfected were significantly higher than the other two groups (p < 0.01). Levels among patients with HIV infection alone were significantly higher than those of healthy controls (p < 0.05). Following 4 weeks of chemotherapy nitrite levels declined to 144.5 ± 34.4 nmol/ml among the HIV/TB coinfected. These were significantly lower than at start of therapy (p < 0.05). There was no correlation between CD4 counts and nitrite levels.

Mean nitrite levels among the HIV/TB coinfected, those with HIV infection alone and healthy controls were 207.6 ± 48.8 nmol/ml, 99.7 ± 26.5 nmol/ml and 46.4 ± 16.2 nmol/ml, respectively. Levels among the HIV/TB coinfected were significantly higher than the other two groups (p < 0.01) and those among patients with HIV infection alone were significantly higher than those of healthy controls (p < 0.05).

Serum citrulline levels are shown in figures 3 and 4. Mean serum citrulline levels in the HIV/TB coinfected were 1446.8 ± 468.8 nmol/ml and those with HIV infection alone were 880.8 ± 434.8 nmol/ml. Healthy controls had levels of 486.6 ± 212.5 nmol/ml. Levels among HIV/TB coinfected were significantly higher than the other two groups (p < 0.01) and those with HIV infection alone had significantly higher levels than controls (p < 0.05). Therapy for TB among the HIV/TB coinfected for 4 weeks resulted in a significant decline to 1116.2 ± 388.6 nmol/ml (p < 0.05). There was no correlation between CD4 counts and citrulline levels.

Mean serum citrulline levels in the HIV/TB coinfected, those with HIV infection alone and healthy controls were 1446.8 ± 468.8 nmol/ml, 880.8 ± 434.8 nmol/ml and 486.6 ± 212.5 nmol/ml, respectively. Levels among HIV/TB coinfected were significantly higher than the other two groups (p < 0.01) and those with HIV infection alone had significantly higher levels than controls (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Our results showing that NO production is elevated among patients with HIV infection and still higher in those with coinfection with TB suggest a role for NO among these individuals. Further, we have demonstrated a decline in NO production among the HIV/TB coinfected following four weeks of antitubercular therapy.

NO has been shown to modulate several immune functions.[24, 25] There have, however, been some contrasting effects attributed to NO. It upregulates proliferation and increases glucose uptake by T lymphocytes, while other reports have suggested that it inhibits T cell activation.[26, 27] HIV infected patients are known to have elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, especially tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α.[11] These are powerful activators of HIV replication.[28] Cytokines produced in response to cell activation can to stimulate iNOS in a autocrine or paracrine manner.

The significance of NO production in HIV infection has been well established. There is an accumulation of NO metabolites, nitrite and nitrate, in individuals who have neurological complications.[29] Nitrite and citrulline levels are elevated among those HIV infected individuals who have no opportunistic infection.[11] There is also evidence to show an association between high levels of virus load and increase NO production in the serum of HIV infected patients.[30] Consequently, production of large amounts of NO by macrophages could be a leading cause of lymphocyte inactivation and induction of persistent immunosuppression.[31]

Evidence for the role of iNOS in TB comes from several studies. NO has been demonstrated to kill 99% Myco. tub. in culture in two days at a concentration of 90 ppm.[32] iNOS inhibitors exacerbate infection in macrophages and mice treated during acute or chronic phase of disease.[33] Myco tub grows rapidly and kills mice that have been rendered selectively deficient in iNOS.[34]

Elevated levels of NO in HIV infection may be due to cytokines, mainly TNF-α and interleukin-6.[35] Both these cytokines play an important role in TB too as NO levels may be stimulated directly by Myco. tub.[36] It is likely that there is some cumulative effect of the increase and, hence, it is easy to see why NO levels are still higher in individuals with the coinfection as demonstrated in this study. It is pertinent to note that NO is involved in HIV-1 replication, especially that induced by TNF-α.[1] There might, therefore, be a self perpetuating mechanism wherein HIV replication leads to increased NO production and the latter increases the rate of HIV multiplication.

Effect of four weeks of therapy in reducing NO production is significant in view of the fact that this coincides with the onset of clinical response. There is reduced immune activation at that time.[20] There are significant clinical implications of this for therapy. Thus, while chemotherapy cures Myco. tub. infection in immunocompetent mice it fails to do so in iNOS-deficient mice.[38] Further, some commonly used drugs that are tuberculocidal in vitro are comparably effective in vivo only with the help of iNOS.[38] In effect chemotherapy might be more beneficial to immunocompromised hosts if accompanied by delivery of a source of NO. Sensitization of tubercle bacilli to NO might reduce the time for chemotherapeutic benefit in immunocompetent hosts and might bring down the incidence of treatment interruption and consequent drug resistance. Since all the patients in the study received rifampicin, the role of the latter as an anti-inflammatory agent needs some consideration. Rifampicin activates the human glucocorticoid receptor.[39] Transient expression of wild-type, deleted or mutated glucocorticoid receptors and sucrose density gradient sedimentation studies have suggested that the drug binds to the receptor with the physiological consequence that this antibiotic acts as an immunosuppressive agent.[39] Four weeks can produce an anti-inflammatory effect to be produced enough to reduce the level of immune activation reflecting in a decrease in NO production. This is likely to have been abetted by a decrease in the level of immune activation due to a decrease in bacillary load and antigenic stimulation.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that NO production is elevated among patients with HIV infection and is still higher in those with coinfection with TB and that these levels decline with four weeks of anti-tubercular therapy. Taken along with other studies mentioned previously there may be a case to suggest that NO plays a deleterious role in HIV infection. It would be interesting to see what effect NOS inhibitors might produce if combined with standard antitubercular therapy in HIV/TB coinfected.

References

Jimenez JL, Gonzalez-Nicholas J, Alvarez S, Fresno M, Munoz-Fernandez MA: Regulation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type I replication in Human T Lymphocytes by Nitric Oxide. J Virol. 2001, 75: 4655-63. 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4655-4663.2001.

Kroncke KD, Feheel K, Kolb-Bachofen V: Inducible nitric oxide synthase in human diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998, 113: 147-56. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00648.x.

Moncarda S, Palmer RM, Higgs AE: Nitric oxide: Physiology, pathophysiology and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1992, 43: 109-42.

Wanchu A, Khullar M, Sud K, Sahkuja V, Thennarasu K, Sud A, Bambery P: A Cross-sectional Analysis of Serum and Urine Nitrite and Citrulline Levels in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2001, 7: 10-5.

Wanchu A, Khullar M, Sud A, Bambery P: Elevated Nitric Oxide Production in Patients with Primary Sjogren's Syndrome. Clinical Rheumatology. 2000, 19: 360-4. 10.1007/s100670070028.

Wanchu A, Khullar M, Sud A, Bambery P: Nitric Oxide Production is increased in patients with Inflammatory Myositis. Nitric Oxide: Biology and chemistry. 1999, 3: 454-8. 10.1006/niox.1999.0261.

Wanchu A, Khullar M, Sud A, Deodhar SD, Bambery P: Elevated Urinary Nitrite and Citrulline levels in patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Inflammopharmacology. 1999, 7: 155-61.

Schmidt HHW, Walter U: NO at work. Cell. 1994, 78: 918-25.

Zangerle R, Fuchs D, Reibnegger G, et al: Serum nitrite plus nitrate in infection with human immunodeficiency virus type-1. Immunobiology. 1995, 193: 59-70.

Hermann E, Idziorek T, Kusnierz JP, Mouton Y, Capron A, Bahr GM: Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of lymphocyte apoptosis and HIV-1 replication. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1997, 19: 387-97. 10.1016/S0192-0561(97)00060-X.

Wanchu A, Khullar M, Bhatnagar A, Sud A, Bambery P, Singh S: Pentoxiphylline Reduces Nitric Oxide Production among Patients with HIV Infection. Immunology Letters. 2000, 74: 121-5. 10.1016/S0165-2478(00)00241-8.

Evans TG, Rasmussen K, Wiebke G, Hibbs JB: Nitric oxide synthesis in patients with advanced HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994, 97: 83-6.

Wang CH, Lin HC, Liu CY, Huang KH, Huang TT, Yu CT, Kuo HP: Upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cytokine secretion in peripheral blood monocytes from pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001, 5: 283-91.

Wang CH, Kuo HP: Nitric oxide modulates interleukin-1beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha synthesis and disease regression by alveolar macrophages in pulmonary tuberculosis. Respirology. 2001, 6: 79-84. 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00302.x.

Garcia M, del Llano AM, Cruz-Colon E, Saavedra S, Lavergne JA: Characteristics of nitric oxide-induced apoptosis and its target cells in mitogen-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV+ subjects. Immunol Invest. 2001, 30: 267-87. 10.1081/IMM-100108163.

Mannick JB, Stamler JS, Teng E, Simpson N, Lawrence J, Jordan J, et al: Nitric oxide modulates HIV-1 replication. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999, 22: 1-9.

Gonzalez-Nicolas J, Resino S, Jimenez JL, Alvarez S, Fresno M, Munoz-Fernandez MA: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and nitric oxide in vertically HIV-1-infected children: implications for pathogenesis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2001, 12: 437-44.

Zangerle R, Steinhuber S, Sarcletti M, Dierich MP, Wachter H, Fuchs D, et al: Serum HIV-1 RNA levels compared to soluble markers of immune activation to predict disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998, 116: 228-39. 10.1159/000023949.

Selwyn PA, Hartel D, Lewis VA, et al: A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1989, 320: 545-50.

Wanchu A, Arora S, Bhatnagar A, Sud A, Bambery P, Singh S: Decline in Beta-2 microglobulin levels after anti-tubercular therapy among HIV/TB infected individuals. Indian Journal of Chest Diseases and Allied Sciences. 2001, 43: 211-5.

Schon T, Gebre N, Sundqvist T, Aderaye G, Britton S: Effects of HIV co-infection and chemotherapy on the urinary levels of nitric oxide metabolites in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1999, 31: 123-6. 10.1080/003655499750006137.

Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnock JS, Tannenbaum SR: Analysis of nitrate, nitrite and (15N) nitrate in biological fluids. Ann Biochem. 1982, 126: 131-8.

Boyde TR, Rahamatullah M: Optimization of conditions for the calorimetric determination of citrulline, using diacetyl monoxime. Ann Biochem. 1980, 107: 424-31.

Huang FP, Niedbala W, Wei QX: Nitirc oxide regulates Th1 cell development through the inhibition of IL-2 synthesis by macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1998, 28: 4060-70. 10.1002/1521-4141(199812)28:12<4062::AID-IMMU4062>3.0.CO;2-K.

Moilanen E, Vapaatalo H: Nitric oxide in inflammation and immune response. Ann Med. 1995, 27: 359-67.

Lander HM, Sehajpal P, Levine DM, Novogrodsky A: Activation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by nitric oxide-generating compounds. J Immunol. 1993, 150: 1509-16.

Williams SM, Noguchi S, Henkart PA, Osawa Y: Nitric oxide synthase plays a signaling role in TCR-triggered apoptotic death. J Immunol. 1998, 161: 6526-31.

Fauci AS: Host factors in the pathogenesis of HIV disease. Antibiot Chemother. 1996, 48: 4-12.

Giovannoni G, Miller RF, Heales SJ, Land JM, Harrioson MJ, Thompson EJ: Elevated cerebrospinal fluid and serum nitrate and nitrite levels in patients with central nervous system complications of HIV-1 infection: a correlation with blood-brain – barrier dysfunction. J Neurol Sci. 1998, 156: 53-8. 10.1016/S0022-510X(98)00021-5.

Torre D, Ferrario G, Bonetta G, Speranza F, Zeroli C: Production of nitric oxide from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes of patients with HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1995, 9: 979-80.

Torre D, Ferrario G: Immunological aspects of nitric oxide in HIV-1 infection. Med Hypotheses. 1996, 47: 405-7.

Long R, Light B, Talbot JA: Antimicrob agents Chemother. 1999, 43: 403-5.

Yu K, Mirchell C, Xing Y, Magiliozzo RS, Bloom RS, Chan J: Tuber Lung Dis. 1999, 79: 191-8. 10.1054/tuld.1998.0203.

MacMiking JD, North RJ, La Course R: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94: 5243-8. 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5243.

Bergamini A, Faggioli E, Bolacchi F, et al: Enhanced production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 due to prolonged response to lipopolysaccharide in human macrophages infected in vitro with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1999, 179: 832-42. 10.1086/314662.

Mohan VP, Scanga CA, Yu K, et al: Effects of tumour necrosis factor alpha on host immune response in chronic persistent tuberculosis: Possible role for limiting pathology. Infection Immun. 2001, 69: 1847-55. 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1847-1855.2001.

Immanuel C, Rajeswari R, Rahman F, Kumaran PP, Chandrasekaran V, Swamy R: Serial evaluation of serum neopterin in HIV seronegative patients treated for tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001, 5: 185-90.

Nathan C, Shiloh MU: Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000, 97: 8841-8. 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8841.

Calleja C, Pascussi JM, Mani JC, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ: The antibiotic rifampicin is a nonsteroidal ligand and activator of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Natr Med. 1998, 4: 92-6.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/2/15/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None for all the authors

Authors Contributions

Author 1 AW conceived the study, compiled the clinical data, analyzed part of the data and drafted the manuscript

Author 2 AB carried out the flowcytometry work for the study

Author 3 MK carried out the spectrophotometric analysis for the study

Author 4 AS participated in design of the study and analyzed part of the data

Author 5 PB participated in the design and coordination of the study

Author 6 SS participated in the design and coordination of the study

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wanchu, A., Bhatnagar, A., Khullar, M. et al. Antitubercular therapy decreases nitric oxide production in HIV/TB coinfected patients. BMC Infect Dis 2, 15 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-2-15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-2-15