Abstract

Background

Current estimates suggest over 218,000 individuals in Australia are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus. The majority of these people are migrants and refugees born in hepatitis B endemic countries, where attitudes towards health, levels of education, and English proficiency can be a barrier to accessing the Australian health care system, and best managing chronic hepatitis B. This study aimed to assess the knowledge of transmission and consequences of chronic hepatitis B among these patients.

Method

A prospective study was conducted between May and August 2012. Patients with chronic hepatitis B were recruited from three Royal Melbourne Hospital outpatient clinics. Two questionnaires were administered. Questionnaire 1, completed during observation of a prospective participants’ consultation, documented information given to the patient by their clinician. After the consultation, Questionnaire 2 was administered to assess patient demographics, and overall knowledge of the effect, transmission and treatment of hepatitis B.

Results

55 participants were recruited. 93% of them were born overseas, 17% used an interpreter, and the average time since diagnosis was 9.7 years.

Results from Questionnaire 1 showed that the clinician rarely discussed many concepts. Questionnaire 2 exposed considerable gaps in hepatitis B knowledge. Few participants reported a risk of cirrhosis (11%) or liver cancer (18%). There was a high awareness of transmission routes, with 89% correctly identifying sexual transmission, 93% infected blood, and 85% perinatal transmission. However, 25% of participants believed hepatitis B could be spread by sharing food, and over 50% by kissing and via mosquitoes. A knowledge score out of 12 was assessed for each participant. The average score was 7.5. Multivariate analysis found higher knowledge scores among those with a family member also diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B and those routinely seeing the same clinician (p = 0.009 and p = 0.002, respectively).

Conclusion

This is the largest Australian study assessing knowledge and understanding of the effect, transmission, and treatment of hepatitis B among chronically infected individuals. The findings highlight the knowledge gaps and misconceptions held by these patients, and the need to expand education and support initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is one of the most common chronic infections affecting up to 350 million people worldwide [1]. It is the second most important known human carcinogen after tobacco [1, 2] and was estimated to have resulted in the deaths of 786,000 people in 2010 [3].

The prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) in Australia has been estimated at approximately 1% of the population, affecting over 218,000 individuals in 2011 [4]. The majority of these are migrants from endemic areas, or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

It is estimated that the increasing CHB prevalence in Australia, predominantly attributable to migration, will result in a two to three fold increase in premature mortality from CHB-related liver cancer by 2017 [5, 6], with liver cancer now the fastest increasing cause of cancer deaths in Australians [7]. Early diagnosis and appropriate management mitigates negative outcomes, including reducing the risk of liver cancer [8, 9] and reversing cirrhosis [10].

Recent migrants from non- English speaking hepatitis B endemic countries may have low health literacy [11], which reduces their capacity to navigate the Australian health care system and is a barrier to comprehending concepts such as liver disease, viral transmission, and antiviral treatment. Combined with fear of stigma, complications and misconceptions, this can be stressful and debilitating [12] and results in suboptimal management for the individual and ongoing transmission to susceptible contacts [13].

Improving understanding of hepatitis B in priority populations and enhancing access to diagnosis and care are key recommendations of Australia’s Second National Hepatitis B Strategy 2014-2017 [14]. Regular monitoring including clinical reviews and appropriate investigations are essential for all people with CHB [15]. Reducing alcohol consumption [16] and smoking cessation also reduce progression to advanced liver disease [17], as does recognition of symptoms associated with disease progression. Those receiving antiviral treatment need to be aware of the potentially indefinite duration of treatment, and that non-adherence allows viral rebound and/or resistance leading to adverse health outcomes [18]. Initiatives to improve testing and vaccination for contacts, and increased monitoring, treatment and educational options for those infected, are essential for reducing the burden of CHB [15].

In light of the increasing burden of CHB in Australia, and the identified need to improve both engagement with and care delivery for people living with CHB, this study aimed to understand current patients’ knowledge and understanding of the transmission, complications and treatment of CHB, and to investigate factors associated with the degree of knowledge in these individuals, in order to guide improvements in clinical and educational initiatives for the growing number of Australians living with CHB.

Methods

Patient cohort

Adult patients with CHB were recruited from three clinics at the Royal Melbourne Hospital from May to August 2012. Two of these clinics saw only patients with a diagnosis of chronic viral hepatitis, and the third clinic was an immigrant health clinic, seeing a range of infections. Some patients routinely saw the same physician, while others were seen by physicians based upon order of arrival at the clinic. All patients diagnosed with CHB aged over 18 years were eligible for participation. A sample size of 50 was determined based on the time available for the study, the likely number of patients able to be recruited in this time period, and the number of participants required to obtain significant results in a similar study of patients with latent tuberculosis conducted at the Royal Melbourne Hospital [19].

Two survey forms were developed and administered by the one independent researcher (T.D). A piloting period was conducted and some questions altered prior to study commencement. Verbal consent was obtained following an explanation of the study and the entirely voluntary nature of participation.

Questionnaire 1 recorded information given to participants during their follow-up consultation, as observed by the researcher. Questionnaire 2 was administered immediately following the consultation, documenting factors including age, education, country of birth, and if an interpreter was used. It also examined patient knowledge with specific open and closed questions covering transmission and consequences of CHB, and possible treatment. The same interpreter (if required) was used during the consultation and administration of the questionnaire. Interviews were conducted by the one researcher to ensure consistency and accuracy of administration. The questionnaire was read out loud to participants to avoid literacy bias.

Data analysis

A knowledge score was derived based on the answers to five questions in Questionnaire 2 reflecting core knowledge of CHB to provide an overall score out of 12. Points were allocated as follows: one point for identifying hepatitis B as their reason for coming to the clinic, one point for identifying their liver as the affected organ, and another for an outcome such as cirrhosis, liver damage or HCC in their answer of how HBV can affect the body. Half a point was awarded for each correct response to the ten yes or no questions on how HBV can be transmitted. When asked the reason for being treated or not being treated, patients were given one point for identifying the lack or presence of liver damage, and one for mentioning a high or low viral load. Finally, two points were awarded for identifying either reducing alcohol consumption or eating well as factors their doctor mentioned to improve liver health. Data were analysed using Stata v10 (College Station, Texas). Univariate analysis (Wilcoxon rank-sum test and linear regression) was conducted to detect associations between knowledge scores and demographic characteristics. Given the large number of variables assessed relative to sample population size, a parsimonious multivariate model was constructed, including only those variables that showed relatively high degrees of association with knowledge score (in this case those with a p value of less than 0.05 on univariate analysis).

To eliminate any ordinal variation in the model, a forwards and backwards stepwise multivariate regression model was constructed to estimate variables associated with knowledge score (analysed as a continuous variable). The resulting significance of output was determined at p ≤ 0.05 with a coefficient produced for each variable. The coefficient describes a multiplicative factor relating the knowledge score and socio-demographic variable; for example, in the case of gender the coefficient would denote the difference in knowledge score between females and males. In terms of age, it would denote the change in knowledge score per year. All other data were analysed descriptively.

Ethics

This project was approved by the Melbourne Health Human Research Ethics Committee as a quality assurance proposal (approval number QA2012029) and is in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. All participants gave informed consent.

Results

Concepts discussed during consultation with clinician

Questionnaire 1 was completed during standard patient follow-up consultations. No participants were attending a first appointment, and doctors were not given a standard script but were observed in their routine practice.

The risks of sexual transmission, blood transmission and perinatal transmission were discussed in 14.2%, 8% and 8% of consultations respectively. Vaccination of family and sexual contacts was also discussed in 17% and 8% of consultations respectively. Possible life-style changes were raised including reducing alcohol (31%), smoking cessation (19%), and weight loss (7%).

Participants (as assessed via Questionnaire 2)

Of the 58 patients invited to participate, 55 were recruited for the study. Incomplete knowledge data were collected from four during the piloting period, and these results were consequently only included in relevant descriptive analyses.

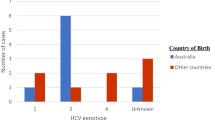

The socio-demographic characteristics of the study group are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The distribution of countries of birth of the patients is shown in Figure 1.

Over half (56%) had completed tertiary education with all but one participant literate in their preferred language. The participant unable to read in either English or their preferred language was also the only participant not to have a family member or friend literate in either language. Of those not able to read English, all others had an English-literate family member or friend. The average time since diagnosis was 9.7 years, with over half having a family member or friend also diagnosed with CHB.

Participant knowledge

Questionnaire 2 responses are shown in Table 2.

To assess transmission knowledge, participants were first asked how HBV could be spread, and then were asked to answer “yes” or “no” to prompted transmission options. All but five participants were aware that HBV could be spread to someone else, with those five being confused about transmission, some answering “yes” or “unsure” to all prompted transmission routes offered.

Over half of the participants were receiving treatment for their CHB, and of these, 55% could name the medication. 76% were aware that treatment duration would likely be life-long.

56% of participants indicated they would like to receive more information. Of those declining more information, some stated they already had enough (most often online), and some just said they did not did want additional information. Participants not using an interpreter were less likely to want more information (53%) compared to those who used one (70%). Of those wanting more information the main preferences were for written or online information both in English and a range of primary languages.

Anecdotally, many patients were keen to share the negative impact that hepatitis B had upon their lives, with one participant saying that it “had destroyed (his) life”. This is further reflected by the fact that 65% of participants were not comfortable discussing their CHB diagnosis with friends and work colleagues, as well as the 7% not comfortable telling their family.

Overall knowledge score

The knowledge score represents responses to five questions that assessed overall knowledge of HBV. The average knowledge score was 7.5 out of a possible 12 points. Only one participant answered all questions correctly with 52% of the study group scoring below 8 and the lowest score being 2.5.

Univariate analysis correlated 16 participant demographic variables with participant knowledge scores (Table 3). All demographic variables that were significantly associated with CHB knowledge are marked with an asterisk. Use of an interpreter and having completed tertiary education approached significance (p = 0.053 and p = 0.059 respectively) and were therefore also included in the multivariate model, as was participant age.

Multivariate analysis

Results of the multivariate analysis are shown in Table 4. Backwards and forwards step-wise regression suggested that having a family member with CHB and having seen the same clinician more than once were associated with a better knowledge score.

Discussion

A limited number of studies have been conducted into the knowledge of people living with CHB regarding their condition [20–22]. This is the largest Australian study to investigate knowledge of CHB among patients attending specialist outpatient clinics. The majority of study participants (93%) were born overseas (62% from Asia, 22% from Africa, 7% from Europe and 9% from Oceania) and had a family member also diagnosed with CHB. This validates observations that the predominant burden of CHB is experienced by migrants from endemic countries where perinatal and early childhood acquisition is common, resulting in multiple affected family members. It also emphasises the cultural diversity seen among individuals with CHB, and the consequential accommodation required by the health system [23]. Knowledge of the effects and risks associated with CHB was low in over half the participants, and there were major misconceptions regarding HBV transmission. There was significantly higher knowledge among individuals with a family member also diagnosed with CHB, and among patients routinely seeing the same doctor.

Important knowledge gaps were identified, for example, the majority of participants lacked understanding about the sequelae of CHB beyond its effect on the liver, with one answering that it affected the lungs. Although CHB is often asymptomatic, complications can occur, and patients should be aware of symptoms that could indicate progressive disease. Our findings contrast with a Malaysian study [24] where participants had a greater knowledge of symptoms such as jaundice and fatigue (55% and 54% respectively). However, unlike the present study, which used both open and closed questioning, the Malaysian study used only prompted yes/no questions, potentially limiting the comparability of these results.

The majority (89%) of participants were aware that HBV can be sexually transmitted, which is higher than the 79-80% reported in previous studies [24, 25]. Moreover, whereas only 6.8% of participants in the Malaysian study [24] knew that HBV was not spread by sharing food, 75% of patients questioned in the present study were aware of this. That HBV can be spread by sharing food and eating utensils is a common misconception, especially among Asian communities, where hepatitis A prevention strategies were promoted following outbreaks in China in 1988 [26]. As hepatitis A is spread via the faecal-oral route, prevention strategies included not sharing food or eating utensils, and this has since been confused with HBV transmission routes.

Over half of participants in our study believed HBV could be spread via kissing or mosquito bites, and 20% by breathing. Such misconceptions have been found by similar studies in other countries [27–31]. These misconceptions can have very deep and negative impacts on those affected, constituting an unnecessary and preventable burden. Dispelling these misconceptions is important for improving the quality of life of those infected [32, 33], and increasing awareness in the general community to reduce the stigma that arises from lack of knowledge.

Only four participants showed an understanding of the virus’s effect on the liver and how this related to their treatment status. During consultations terms such as viral load, and viral activity were commonly used, but we do not know if they were always understood by participants.

Some participants showed a passive approach towards their health, deferring to their doctor’s advice as their reason for treatment and appointment attendance. Passivity towards health has been correlated with low health literacy [34] and highlights the need for patient engagement as well as education, and this is particularly pertinent among recently arrived migrants who may have many competing priorities. It is important to note that the group interviewed represents those engaged with the healthcare system and attending specialist appointments. There are many individuals with CHB not engaged with the healthcare system, and more than 100,000 Australians estimated to be living with undiagnosed CHB [4], whose health literacy may be even lower.

The results of Questionnaire 1 suggest that patients are generally not provided with detailed information during ongoing monitoring of CHB. However, it is clear that some participants would benefit from repetition of important transmission and management information. While it could be assumed all participants were provided with extensive information upon diagnosis, it is possible that long-term retention of this information is not universal. Therefore, assumptions of knowledge may not be valid, irrespective of whether the cause is never having been provided with the information, or not recalling it.

Better knowledge was seen among those with a family member also diagnosed with CHB, possibly by providing a direct source of information following diagnosis. Having a relative with the same condition, especially if they have suffered the sequelae of liver dysfunction, may also promote communication, engagement, support and encouragement for regular monitoring [33]. Discussing the diagnosis with people sharing cultural and linguistic ties may also be conducive to better knowledge, although this could also be a source of the many myths regarding CHB infection [12]. Community-outreach programs based on providing culturally and linguistically salient information have been internationally recognised for effectively disseminating information among Hispanic/Latino communities in the United States [35].

Seeing the same the doctor has been shown to improve patient knowledge and management of chronic conditions such as asthma [35]. Our results validate this as positive associations with knowledge score were observed among patients having seen the clinician before (p = 0.02) and with increasing years seeing the same clinician (p = 0.003). A possible explanation is that with return visits, the treating clinician can incrementally educate the patient and reinforce previous discussions although more research in this area is needed. It also provides consistency and familiarity for the patient. This should be incorporated into clinical practice aimed at improving patient engagement with the healthcare system and reducing the number of patients lost to follow up.

During the study period, between 9%-31% of patients failed to attend their appointments (all clinic patients rather than only those with CHB). This provides an indication of the difficulty of monitoring and maintaining contact with patients who experience language barriers and may change residential address frequently. Wu et al [25] cited inconvenience as a significant barrier to healthcare access among 40% of participants with CHB, with after-hour clinics having higher attendance rates. The clinics in our study operated from 9 am-12.30 pm sometimes with considerable delays in seeing patients. The finding that the majority of patients stated that they did not feel comfortable disclosing the infection to their friends and colleagues highlights the potential difficulty of attending appointments during business hours.

This study had several limitations. As recruitment was from clinics based in a major Victorian hospital, it does not provide information about patients from other settings such as general practice or rural clinics. Our study group may also have had a slight bias towards those not using an interpreter, as on two occasions the interpreter was not able to complete the interview, preventing those patients from participating. Furthermore, patients attending these clinics are already engaged with the healthcare system, and may not be representative of the general population living with hepatitis B.

Patient acceptance of the research was high, with 55 of 58 invited agreeing to participate. However, with a number of variables assessed for impact on knowledge score, and considered for inclusion in multivariate analysis, this analysis may have lacked power to detect some factors truly associated with knowledge score (type II error).

Conclusion

As HBV prevalence and attributable liver cancer incidence increases in Australia and other developed countries, health service provisions for people with CHB will need to improve and expand, and should involve education and support for those chronically infected and their families. There are many HBV patient resources, both online and in print, available in a number of priority languages (for example http://www.hepbhelp.org.au). Liaison nurses and community self-management programs also exist to support and educate this group. These resources are currently underused and it was one intention of this research to provide results that challenge clinicians to aim for improved engagement and continued education of this patient group, especially for long-term patients. These results also highlight the need to educate patients regarding common misconceptions in addition to actual transmission routes. A better understanding of CHB will improve compliance and monitoring and may reduce the significant morbidity, anxiety and stress surrounding CHB infection.

Abbreviations

- CHB:

-

Chronic hepatitis B

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B Virus.

References

Lavanchy D: Worldwide epidemiology of HBV infection, disease burden, and vaccine prevention. J Clin Virol. 2005, 34: 1590-8658.

Previsani N, Lavanchy D: Hepatitis B. Geneva: Department of Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Response. Edited by: Organisation WH: World Health Organisation. 2002

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Barker-Collo S, Bartels DH, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bhalla K, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Boufous S, Bucello C, Burch M: Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380 (9859): 2095-2128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0.

MacLachlan JH, Allard N, Towell V, Cowie BC: The burden of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Australia, 2011. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013, 37 (5): 415-422.

Wallace J: National Hepatitis B Needs Assessment 2007. 2007

Butler J, Korda R, Watson K, Watson AR: The impact of chronic hepatitis B in Australia: Projecting mortality, morbidity and economic impact. Edited by: Health ACfERo. 2009, Canberra: The Australian National University, 7

MacLachlan JH, Cowie BC: Liver cancer is the fastest increasing cause of cancer death in Australians. Med J Aust. 2012, 197 (9): 492-493.

Carville KS, Cowie BC: Recognising the role of infection: preventing liver cancer in special populations. Cancer Forum. 2012, 36 (1): 21-24.

Papatheodoridis GV, Lampertico P, Manolakopoulos S, Lok A: Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients receiving nucleos(t)ide therapy: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2010, 53 (2): 348-356. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.035.

Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, Afdhal N, Sievert W, Jacobson IM, Washington MK, Germanidis G, Flaherty JF, Schall RA, Bornstein JD, Kitrinos KM, Subramanian GM, McHutchison JG, Heathcote EJ: Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013, 381 (9865): 468-475. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61425-1.

Australian Bureau of Statistics: Health Literacy, Australia. Australian Social Trends. 2006, Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

Wallace J, McNally S, Richmond J, Hajarizadeh B, Pitts M: Managing chronic hepatitis B: A qualitative study exploring the perspectives of people living with chronic hepatitis B in Australia. BMC Res Notes. 2011, 4 (1): 45-51. 10.1186/1756-0500-4-45.

Tran TT: Understanding cultural barriers in hepatitis B virus infection. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009, 76 (3): 10-13.

Second National Hepatitis B Strategy 2014-2017. 2014, Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health

MacLachlan J, Cowie B: Chronic hepatitis B What’s new?. Aust Fam Physician. 2013, 42: 448-451.

El Serag HB: Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012, 142 (6): 1264-10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061.

Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F: Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: Special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008, 48 (2): 335-352. 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011.

Liaw Y-F, Chu C-M: Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009, 373 (9663): 582-592. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60207-5.

Butcher KL: Patient Understanding of Latent Tuberculosis its Treatment and Treatment Side Effects: A Prospective Study. Honours Thesis. 2009, Melbourne: The University of Melbourne

Preston-Thomas A, Fagan P, Nakata Y, Anderson E: Chronic hepatitis B - Care delivery and patient knowledge in the Torres Strait region of Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2013, 42 (4): 225-231.

Wallace J, McNally S, Richmond J: National Hepatitis B Needs Assessmen. 2008, Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University

Drazic YN, Caltabiano ML: Chronic hepatitis B and C: Exploring perceived stigma, disease information, and health-related quality of life. Nurs Health Sci. 2013, 15: 172-178. 10.1111/nhs.12009.

Cowie B: The linguistic demography of Australians living with chronic hepatitis B. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2011, 35 (1): 12-15. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00634.x.

Mohamed R, Ng C, Tong W, Abidin S, Wong L, Low W: Knowledge, attitudes and practices among people with chronic hepatitis B attending a hepatology clinic in Malaysia: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012, 12 (1): 601-10.1186/1471-2458-12-601.

Wu H: Sociocultural factors that potentially affect the institution of prevention and treatment strategies for hepatitis B in Chinese Canadians. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009, 23 (1): 31-

American Society for Reproductive Medicine Birmingham Alabama: Hepatitis and reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2004, 90 (Supple 3): 1754-1764.

Nishimura A, Shiono P, Stier D, Shallow S, Sanchez M, Huang S: Knowledge of Hepatitis B Risk Factors and Prevention Practices among Individuals Chronically Infected with Hepatitis B in San Francisco, California. J Community Health. 2012, 37 (1): 153-158. 10.1007/s10900-011-9430-2.

Takahashi L, Kim A, Sablan-Santos L, Quitugua L, Aromin J, Lepule J, Maguadog T, Perez R, Young L, Young S: Hepatitis B Among Pacific Islanders in Southern California: How is Health Information Associated with Screening and Vaccination?. J Community Health. 2011, 36 (1): 47-55. 10.1007/s10900-010-9285-y.

Salahuddin M, Rauf MUA, Noorani MM: Knowledge of patients attending free hepatiti clinic at civil hospital Karachi about hepatitis ‘B’ and ‘C’. Med Channel. 2010, 16 (3): 365-367.

Taylor VM: Hepatitis B knowledge and practices among Chinese immigrants to the United States. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prevention. 2006, 7 (2): 313-

Khuwaja AK, Qureshi R, Fatmi Z: Knowledge about hepatitis B and C among patients attending family medicine clinics in Karach. East Mediterr Health J. 2002, 8 (vi): 787-793.

Cotler SJ, Cotler S, Xie H, Luc BJ, Layden TJ, Wong SS: Characterizing hepatitis B stigma in Chinese immigrants. J Viral Hepatitis. 2012, 19 (2): 147-152. 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01462.x.

Lee H, Yang JH, Cho MO, Fawcett J: Complexity and uncertainty of living with an invisible virus of hepatitis B in Korea. J Cancer Educ. 2010, 25 (3): 337-342. 10.1007/s13187-010-0047-4.

Smith SK, Dixon A, Trevena L, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ: Exploring patient involvement in healthcare decision making across different education and functional health literacy groups. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 69 (12): 1805-1812. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.056.

Quail G: Does attending the same doctor improve outcome in chronic disease?. Australian Military Med. 2006, 15 (1): 18-

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/537/prepub

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants, their families and interpreters for their contributions to this study. We also thank clinic staff for their assistance. None of the authors have a conflict of interest relating to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TD designed and administered the questionnaire, analysed the results and wrote the manuscript. BC assisted in questionnaire design, statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. BAB assisted in study design and analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. KL assisted in study design and analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. JML assisted with statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. CM conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahl, T.F., Cowie, B.C., Biggs, BA. et al. Health literacy in patients with chronic hepatitis B attending a tertiary hospital in Melbourne: a questionnaire based survey. BMC Infect Dis 14, 537 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-537

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-537